Child Care Affordability Is Out of Reach for Many Low-Income Hispanic Households

Oct 10, 2019

Research Publication

Child Care Affordability Is Out of Reach for Many Low-Income Hispanic Households

Author

Overview

Hispanica households tend to have both high levels of parental employment and low levels of income,1 making access to good-quality child care a critical need for these families. Child careb has the potential to serve as a two-generation investment strategy, with both short- and long- term economic and social benefits, by supporting parents’ ability to work and providing enrichment opportunities for children.2,3

Affordability is a key factor shaping families’ access to care.4 Even when communities have an adequate supply of good-quality child care that meets parents’ and children’s needs and families are aware of these options, care remains inaccessible if costs are beyond household budgets. The U.S. Department of Health and Human Services (HHS) recommends that child care be considered affordable if family out-of-pocket costs are equivalent to 7 percent or less of total household income.5 Yet in every state in the nation, the average price of formal child care (e.g., centers and licensed or regulated family child care) exceeds this recommended benchmark of affordability.6

To reduce financial barriers and support more equitable access, several federal and state programs provide low-income families with no- or low-cost early care and education (ECE) options, including Head Start, public pre-kindergarten, and subsidies through the Child Care and Development Fund (CCDF). While the reach of these programs has expanded over the years, funding constraints mean that not all eligible children can be served.7,8 In the absence of such programs or when co-payments are high, low-income families are often priced out of the formal, licensed care settings that tend to be more stable and of higher quality than more informal arrangements.9,10

Affordability and its role in equitable access to good-quality care are key issues for low-income Hispanic families. Employed Latino and black parents are much more likely to have low incomes than working parents who are white or Asian/Pacific Islander, even at similar levels of employment, and are therefore likely to be disproportionately affected by affordability issues.11 Indeed, Latino parents of young children who report difficulty finding child care are more likely to identify cost as the primary barrier.12

This brief examines child care costs and affordability for low-incomec Hispanic households with at least one child ages 0 to 5, the period in which families’ care needs tend to be most acute. Given that care is often needed for older children as well, to cover gaps between school and parents’ work schedules, our household-level analysis of child care spending includes all arrangements for children younger than age 13 who live in the home. Using nationally representative data from the 2012 National Survey of Early Care and Education (NSECE), we report on Hispanic households’ weekly out-of-pocket child care costs, and the percentage of household income this represents. We examine costs separately for immigrant and nonimmigrant Hispanic householdsd given evidence that some aspects of care access and utilization (including receipt of subsidies) vary by parents’ nativity status.13 For comparison purposes, we also report cost data for low-income non-Hispanic, nonimmigrant, and white and black households.e Finally, to better understand associations between costs and utilization for Latinos, we examine the amounts and types of care being used by Hispanic households with three different levels of child care spending: those with no out-of-pocket costs, those paying affordable costs (≤ 7% of income), and those with high costs (> 7% of income).

Key Findings

- About 6 in 10 low-income Hispanic households with young children using child care have no out-of-pocket expenses because they use arrangements that are either provided at no cost or are fully subsidized.f This is similar to the shares of low-income white and black households with no out-of-pocket expenses.

- Four in 10 low-income Hispanic households using child care have some out-of-pocket costs, and most of these families spend a significant proportion of their income on child care. The difference in costs for families below and above the federal benchmark of affordability (≤ 7% of total family income) is striking:

- More than three in 10 low-income Latino households using care face high out-of-pocket costs. These households spend an average of roughly $115 per week on care, which represents about one-third of their income.

- Fewer than one in 10 low-income Latino households using care have out-of-pocket costs that are considered affordable according to the federal benchmark. These households spend an average of approximately $20 per week on care, which represents 3 percent of their income.

- Child care utilization patterns for low-income Hispanic households with different levels of child care spending—either no costs, affordable costs, or high costs—look similar on some characteristics, but differ on others.

- Households across all three spending levels use an average of more than two regular providers and approximately 30 to 40 hours of care per week.

- Compared to households that pay out of pocket for care, households with no out-of-pocket costs tend to:

- Use fewer hours of care and slightly fewer providers

- Be less likely to use center-based arrangements

- Be more likely to use unpaid care with a home-based provider

- Within each spending level, immigrant and nonimmigrant Hispanic households have similar utilization patterns, with a few exceptions:

- Among those with no out-of-pocket costs, immigrant households are twice as likely to use center-based arrangements as nonimmigrant households (45% vs. 26%).

- Immigrant households with no out-of-pocket costs are also less likely than their nonimmigrant counterparts to use unpaid home-based arrangements (56% vs. 69%).

Data Source and Methodology

The 2012 National Survey of Early Care and Education (NSECE) is a set of four nationally representative surveys designed to describe the early care and education landscape of the United States from both the supply and demand perspectives. The data presented in this brief are drawn from the NSECE household survey, which collects parent-reported information about child care utilization and costs for a nationally representative sample of households with children under age 13. The NSECE oversampled in low-income areas, resulting in large numbers of low-income families.

This brief focuses on low-income households (defined as those with annual income below 200 percent of the federal poverty threshold) that have at least one child younger than age 6 and reported using nonparental care (for any child younger than age 13) on a regular basis at the time of the survey. Our analytic sample of 2,111 low-income households with young children that are using child care includes 865 Hispanic households, 696 non-Hispanic white households, and 550 non-Hispanic black households.g We present results for the Hispanic sample separately for immigrant households (in which at least one member is foreign-born) and nonimmigrant households (in which all members are U.S.-born) because of the potential implications of household nativity status for access to both child care and child care assistance.

Child care cost and utilization data are analyzed and presented at the household level and capture all regular care arrangements used for any children younger than age 13 living in the home. Descriptive analyses were conducted across several indicators of child care costs and affordability. Significant pairwise differences (by race/ethnicity, nativity, and household spending) are noted in the text, figures, and summary tables. All analyses were conducted in Stata and were weighted to be representative of children living in U.S. households in 2012.

Definitions

Weekly household out-of-pocket child care expenses. In the NSECE household survey, parents reported on payments made by the household for each nonparental care arrangement used for any child younger than age 13 living in the home. Dollar amounts were summed across arrangements to calculate the total paid per week by the household. This variable reflects out-of-pocket costs and does not include subsidies or subsidy reimbursements.

Household uses only no-cost arrangements. An indicator variable was created to identify households with no out-of-pocket child care expenses for any arrangements being used. These no-cost arrangements include publicly funded early childhood programs such as Head Start and public pre-kindergarten, arrangements that are fully subsidized with private or public funds (e.g., CCDF), and care that is provided free of charge to the family by individual caregivers (e.g., grandparent care).

Child care expenses as a share of household income. Out-of-pocket expenses were calculated as a percentage of total household income to capture the share of the household budget that goes toward child care. This percentage is often referred to in the literature as “child care cost burden”; however, in this brief we intentionally use terminology that recognizes the tradeoffs parents make between cost, quality, proximity, and other factors. Moreover, we do not assume that parents consider care expenditures to be a burden given that some may view them as an investment for their child and family.

Affordability of household child care expenses. Households are identified as having affordable costs if they spend 7 percent or less of their income on care, which aligns with the affordability benchmark recommended by the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services (HHS).5 Households paying more than 7 percent of their income are identified as having high costs.

Findings

What percentage of low-income households using child care pay out of pocket?

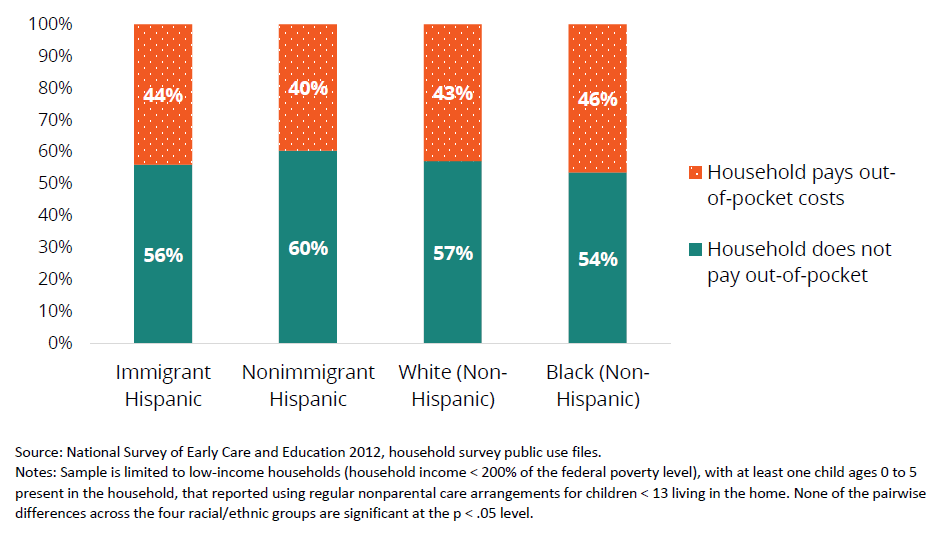

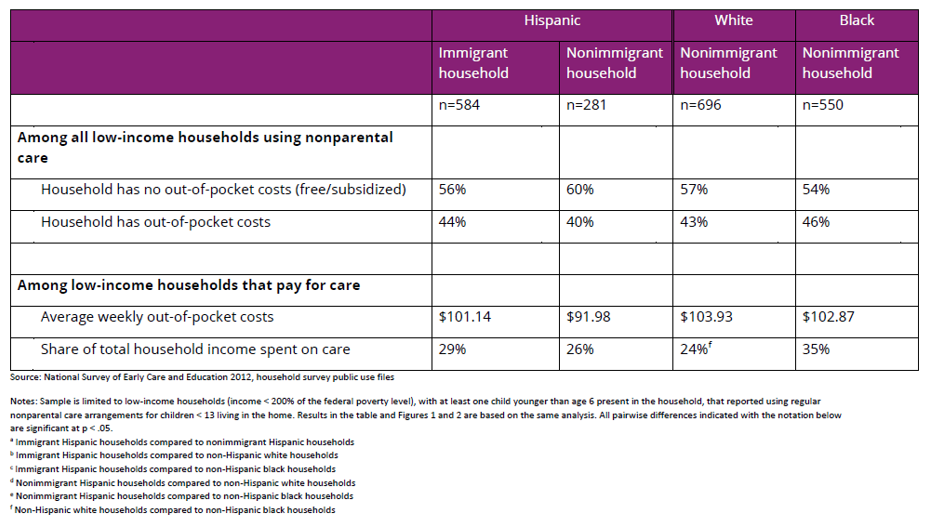

Many low-income Hispanic households that use nonparental care have no out-of-pocket costs because care is either provided for free or it is fully subsidized. As shown in Figure 1 (and Table 1), 56 percent of immigrant Hispanic households and 60 percent of nonimmigrant Hispanic households use only no-cost arrangements, which is statistically similar to the 57 percent of white and 54 percent of black households that use no-cost care. Conversely, this means that 40 to 46 percent of low-income households (Hispanic, white, and black) pay some out-of-pocket child care costs.

Figure 1. Similar to other low-income families, roughly 4 in 10 Hispanic households using child care have out-of-pocket costs

For low-income households that pay out of pocket for care, how much is spent per week and what share of income does this consume?

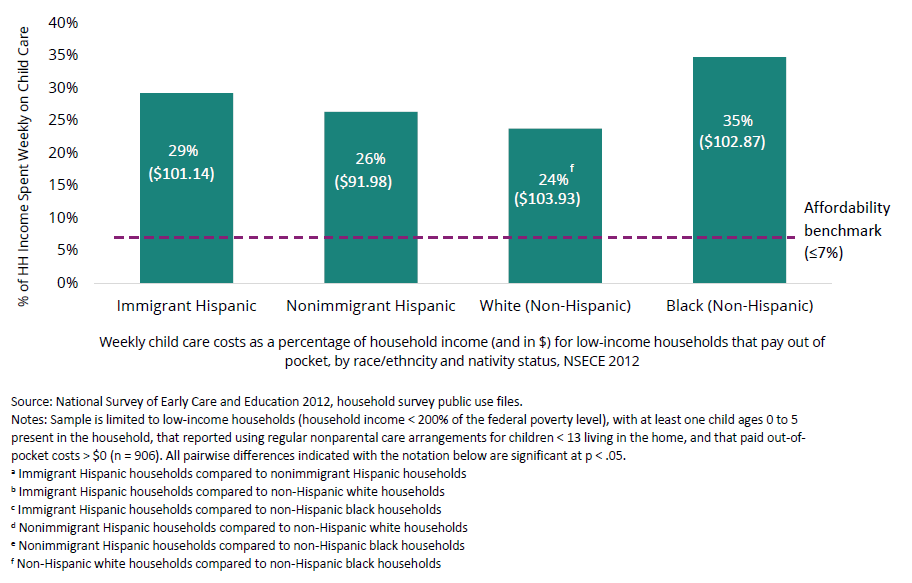

Low-income Hispanics who pay out of pocket for child care tend to face relatively high costs that consume a considerable portion of their household income. Immigrant Hispanic households spend an average of $101.14 per week on care, which is the equivalent of 29 percent of their total household income; nonimmigrant Hispanic households spend an average of $91.98 per week, or 26 percent of household income (Figure 2 and Table 1). Similarly, low-income white and black households that pay out of pocket for child care spend a weekly average of $103.93 and $102.87, or 24 percent and 35 percent of household income, respectively. Notably, for all groups, the average share of income spent on child care is well above the HHS affordability benchmark of 7 percent.

Figure 2. Low-income Hispanic households that pay out of pocket for child care spend an average of more than one-fourth of their total household income (approximately $100 per week)

What percentage of low-income households pay affordable care expenses?

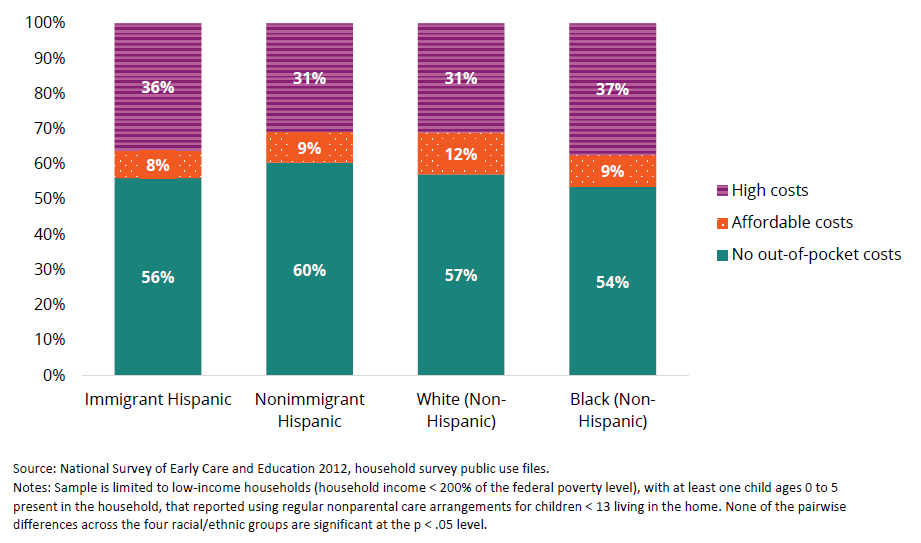

Figure 3 displays the percentages of households using child care that are paying 1) no out-of-pocket costs (no costs), 2) expenses equal to 7 percent or less of their income (affordable costs), and 3) more than 7 percent of their income (high costs). According to this categorization, nearly two-thirds of low-income Hispanic, white, and black households that use child care on a regular basis have arrangements that are either free or affordable, while roughly one-third have high care costs that may strain family budgets and be difficult to sustain.

Figure 3. Similar to other low-income households, roughly one-third of low-income Hispanics with young children pay high out-of-pocket costs for child care.

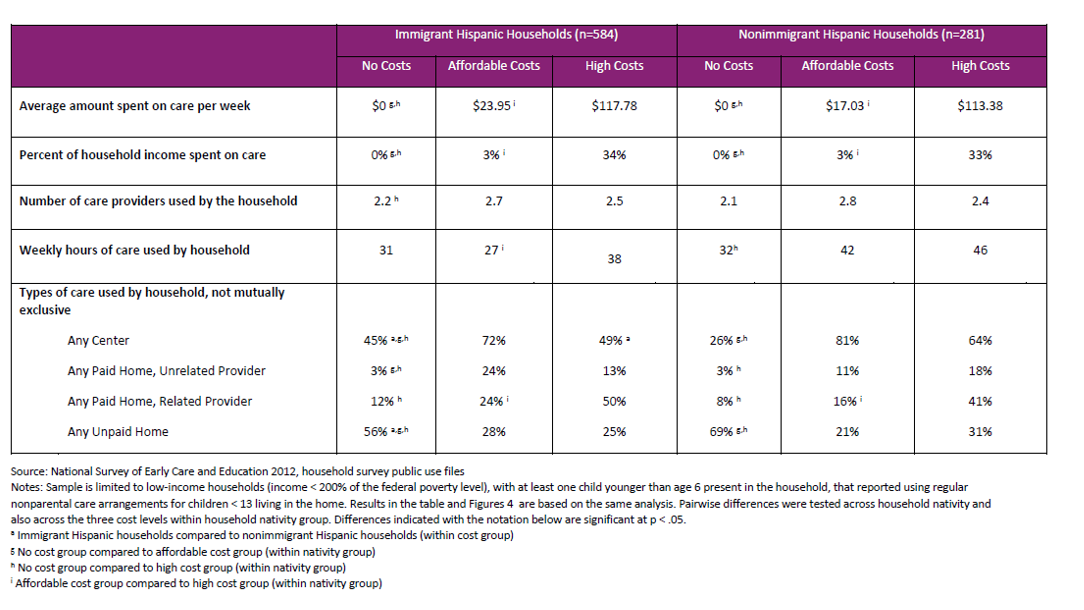

How much care and what types of arrangements are being used by low-income Hispanic households with different levels of child care spending?

Next, we examine the amount and type of care arrangements being used by immigrant and nonimmigrant Hispanic households across the three levels of child care spending described above (no costs, affordable costs, and high costs).

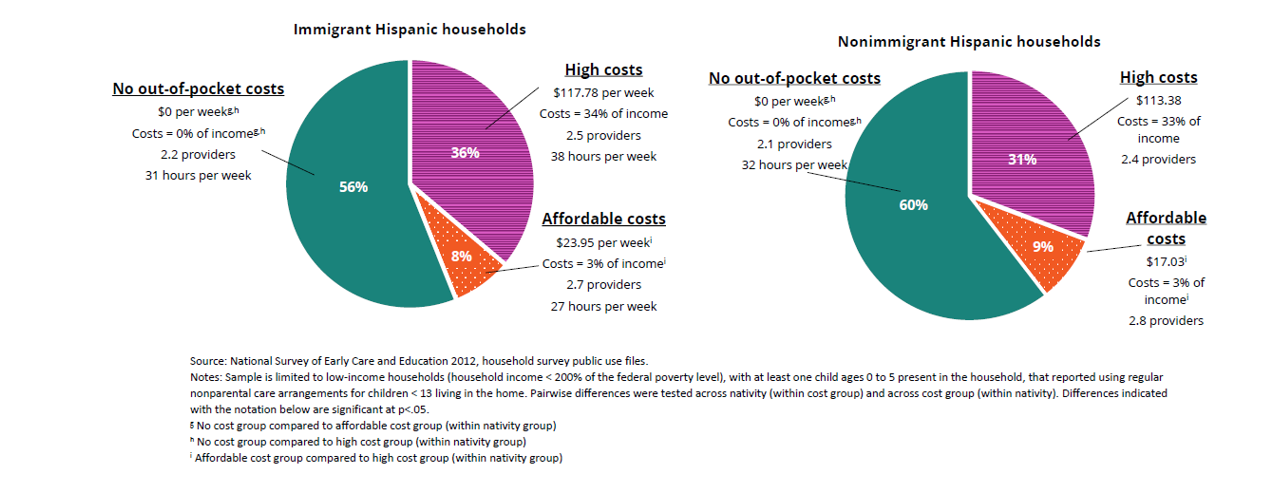

Household spending and amount of care

By definition, Hispanic households in the three cost groups differ in how much they spend on child care, which is reflected in Figure 4. Notably, however, we find that Hispanic families whose costs are above the federal affordability benchmark of 7 percent of income spend considerably more than those whose costs are below the benchmark; in fact, they spend approximately five times as much, on average. Both immigrant and nonimmigrant households in the high costs category pay more than $110 per week, and roughly one-third of their weekly household income for care. By comparison, families in the affordable costs category spend an average of less than $20 per week and 3 percent of income.

We also find that the amount of care—the number of providers and hours of care that households use each week—varies somewhat by spending level; this is not surprising given that costs may be higher when families use more care. However, differences in amounts of care across the three cost groups are not as large as might be expected based on the magnitude of the cost differences (Table 2). Across all cost groups, low-income Hispanic households generally use between 30 and 40 hours of child care per week, and an average of just over two providers or arrangements. Only one group difference related to amount of care reached statistical significance: Among nonimmigrant Hispanic households, those paying high costs use significantly more hours of child care than those paying no out-of-pocket costs.

Figure 4. Average weekly child care costs (in dollars and as a share of income), number of providers and hours of care, by level of costs and Hispanic household nativity

Household spending and types of care

In the final set of results, we examine the types of care arrangements being used by low-income Hispanic households with different levels of child care spending. The categories for types of care capture all regular arrangements used by the household for any child younger than age 13, and the categories are not mutually exclusive (i.e., families may be using more than one type). We distinguish between arrangements that are center-based versus home-based; for the latter, we note whether the family had a prior relationship to the provider (familiar vs. unfamiliar), and whether familiar home-based providers are paid or unpaid.

Table 2 summarizes how low-income Hispanics’ utilization of different types of child care arrangements vary across three levels of household spending (no costs, affordable costs, and high costs) and by household nativity within each level of spending. In general, we find more variation in types of care across different spending levels than between immigrant and nonimmigrant households, although a few differences by nativity status emerged as well.

Among low-income Hispanic households with no out-of-pocket child care costs (Table 2), the most common child care arrangement is unpaid care with a home-based provider. This type of care was reported by roughly 56 percent of immigrant Hispanic households and 69 percent of nonimmigrant Hispanic households with no child care expenses. Previous findings from the 2012 NSECE show that Hispanic parents in poverty are less likely than white and black parents in poverty to have relatives nearby who are available to provide care.14 Immigrant Hispanic parents may be particularly unlikely to have this resource available given that migration often separates family members.

Notably, among low-income Hispanic households with no out-of-pocket costs, use of center care is nearly twice as high among immigrant households than among nonimmigrant households (45% vs. 26%, respectively). Other work from the Hispanic Center supports this finding, suggesting that publicly funded center-based programs like Head Start and public pre-kindergarten may be especially successful in recruiting immigrant families in some communities.15

Finally, use of paid home-based care by households with no out-of-pocket costs is relatively low (3% to 12%), as might be expected. The relatively few households that use home-based care without paying out of pocket are presumably receiving subsidies that cover the cost of care.

Among low-income Hispanic households with affordable care expenses (≤ 7% cost burden), rates of center care use are high, especially among nonimmigrant households (Table 2). Just over 80 percent of nonimmigrant Hispanic households and 72 percent of immigrant Hispanic households with affordable care expenses use a center arrangement. These families may be using subsidized center-based care, where parents are responsible for a co-pay or fees are based on a sliding scale. They may also be using no-cost (fully subsidized) center arrangements and then paying some out-of-pocket costs for additional care needs not covered by center operating hours. As might be expected, use of unpaid home-based care is lower (and use of paid home-based care is higher) among households that have some out-of-pocket costs than among those with no out-of-pocket costs.

The use of paid home-based arrangements with a familiar provider is higher among low-income Hispanic households with high out-of-pocket care expenses (Table 2), than it is among households with no or low child care expenses. This type of care is used by 50 percent of immigrant households with high costs and 41 percent of nonimmigrant households with high costs. Center-based arrangements are also relatively common for this group, used by roughly one out of two households; however, these rates are lower than they are for households with affordable care expenses. Families that cannot access center arrangements that are subsidized may tend to be priced out of this type of arrangement.

Discussion

Child care costs are a key factor in determining whether families can access the types of arrangements that reliably support parents’ employment and provide enriching developmental opportunities for children.4 Low-income families, whose children stand to benefit substantially from high-quality care settings,3 face considerable financial constraints. Recognizing this challenge, federal and state programs such as CCDF subsidies, Head Start, and public pre-kindergarten are designed specifically to increase low-income families’ access to high-quality care by reducing costs. However, many families that are eligible do not receive assistance,8 and national data suggest that roughly four out of 10 low-income families with young children must pay out-of-pocket for care arrangements.2

Hispanic families may be disproportionately affected by child care affordability challenges given their high rates of parental employment (increasing their need for care) at relatively low wages (reducing their ability to purchase care). National census data show that Hispanic parents working full time and year round are the racial/ethnic group most likely to be low-income; 40 percent of Hispanic parents in this category are low-income, compared to 32 percent of black working parents and 13 percent of white working parents.11 In addition, low-income Hispanic families are less likely than non-Hispanic families to access certain forms of child care assistance (e.g., CCDF) when they are eligible to do so, although their participation rates in some publicly funded programs (e.g., Head Start) are on par with non-Hispanic peers.13

Consistent with other national data on low-income working families,2 we find that four out of 10 low-income Hispanic households with young children pay for care, while six out of 10 use only no-cost arrangements. These proportions and families’ average spending on care are similar across low-income Hispanic, white, and black households. That nearly two-thirds of families are able to access arrangements that do not draw on limited household resources might be seen as encouraging news and evidence that policies to reduce financial barriers are having an impact. In particular, our finding that nearly half of immigrant Hispanics with no out-of-pocket expenses use center-based care is consistent with other work showing that ECE programs such as Head Start and public pre-kindergarten can engage in successful outreach to these communities and are generally viewed favorably by parents.15 More information is needed, however, about the range and quality of no-cost arrangements that Hispanic families use, and whether families select these by choice or out of necessity because preferred options are unavailable or unaffordable.

Among the four out of 10 Hispanic households that pay for child care, we find that a majority have expenses well above the HHS recommended affordability benchmark of 7 percent (or less) of household income; on average, these households spend one-third of their weekly income on care. Such high out-of-pocket costs are concerning because they may interfere with families’ self-sufficiency and economic mobility efforts, and may be unsustainable, leading to instability in parents’ employment and/or child care arrangements. Hispanic households in this cost group use a fair amount of both center-based and home-based arrangements. Paying such a large share of income toward care may mean that these families are not receiving child care assistance (because of low take-up, access barriers, or insufficient funding), or that available no- or low-cost arrangements do not fully meet their care needs (e.g., nonstandard hours of care) and they must purchase alternative or additional care at market prices.

Policies that help make child care more affordable for families, especially those with low income, are critical for improving access to the types of care arrangements that support the success of both children and parents.6,16 The CCDF child care subsidy program is the one of the primary federal mechanisms for helping low-income families pay for child care. Yet, Latino children are less likely than their non-Latino peers to be served by CCDF; while 21 percent of eligible non-Hispanic black children and 13 percent of all eligible children receive subsidies, only 8 percent of eligible Hispanic children receive assistance.17

Changes to the CCDF program enacted through the 2014 reauthorization of the Child Care and Development Block Grant, coupled with historic funding increases in 2018, are intended to strengthen the program’s reach, in part through greater investments in consumer education and more family-friendly eligibility policies that are responsive to the employment dynamics of low-income families. The new CCDF regulations finalized in 2016 address affordability most directly by establishing a federal benchmark of affordable family co-payments set at 7 percent or less of household income, and also by giving states greater flexibility to waive co-payments for vulnerable families.5 These new features hold promise for increasing Hispanic families’ access to child care assistance. As states move toward fully implementing the new CCDF requirements, additional work is needed to evaluate their impact on Hispanic families and identify factors that facilitate or impede access to assistance. The literature points to several potential barriers that may disproportionately affect Hispanics; these include mismatches between parents’ employment schedules and available subsidized care options,18 and features of state CCDF policies that increase administrative burden,19 as well as anti-immigration policies and discourse that have reduced families’ comfort level with seeking services for which they are eligible20,21 and increased experiences of discrimination even among U.S.-born Hispanics.22

Whereas earlier research on ECE for Hispanics tended to focus on utilization gaps, we know from recent work that these gaps are closing, especially for 3- to 5-year-olds. Hispanic parents need child care to support high levels of work activity; moreover, they report that they are interested in early learning opportunities for their children.13 The findings presented in this brief show that, like other low-income families using child care, a significant number of Hispanic households spend a high proportion of their income on care arrangements. Next steps in this work will examine in more detail how child care affordability varies across Hispanic families with different household and community characteristics that impact both their need for care and the options accessible to them. Recent analyses of the 2012 NSECE child care cost data using the full sample suggest that affordability (and links between affordability and type of care) varies by such factors as child age, household income, and community urbanicity.23-25

Table 1. Out-of-pocket child care costs for low-income Hispanic, white, and black households

Table 2. Features of child care utilization for low-income Hispanic households with different levels of child care spending

Footnotes

a In this brief, we use the terms “Hispanic” and “Latino” interchangeably.

b We primarily use the term “child care” in this brief rather than early care and education because some of the arrangements included in this household-level analysis of costs may be for school-age children.

c Low-income is used here to refer to households with income below 200 percent of the federal poverty threshold.

d For the purposes of this brief, nonimmigrant households are those in which all members were born in the United States, while immigrant households are those in which at least one member is foreign-born.

e Hereafter these are referred to as white and black households for simplicity.

f Due to data limitations in the public use datafile, and the fact that our household-level analysis collapses across multiple arrangements, we do not distinguish between no-cost care that is provided for free by the provider and care that is no cost to the family because it is subsidized with public or private funds.

g Household racial/ethnic designation is based on respondent reports of the identity of each individual living in the home. For the purposes of this brief, Hispanic households are defined as those in which all members are identified as being of Hispanic heritage. Our analysis sample does not include multi-racial or multi-ethnic households (which may include Hispanic members), nor households identified as Asian, Native Hawaiian, Pacific Islander, or Native American/Alaskan Native, given insufficient sample sizes to examine their potentially unique experiences.

Suggested citation:

Crosby, D., Mendez, J., & Barnes, A. (2019). Child Care Affordability Is Out of Reach for Many Low-Income Hispanic Households. Report 2019-05. Bethesda, MD: National Research Center on Hispanic Children & Families. https://doi.org/10.59377/101t3423h

References

1 Wildsmith, E., Ramos-Olazagasti, M.A., & Alvira-Hammond, M. (2018). The Job Characteristics of Low-Income Hispanic Parents. Bethesda, MD: National Research Center on Hispanic Children & Families. https://hispanicrescen.wpengine.com/publications/the-job-characteristics-of-low-income-hispanic-parents/

2 Malik, R. (2019). Working Families Are Spending Big Money on Child Care. Washington, DC: Center for American Progress. https://www.americanprogress.org/issues/early-childhood/reports/2019/06/20/471141/working-families-spending-bigmoney-child-care/

3 Yoshikawa, H., Weiland, C., Brooks-Gunn, J., Burchinal, M. R., Espinosa, L. M., Gormley, W. T., Ludwig, J., Magnuson, K., Phillips, D., & Zaslow, M. J. (2013). Investing in Our Future: The Evidence Base on Preschool Education. Washington, DC: Society for Research in Child Development. https://www.fcd-us.org/the-evidence-base-on-preschool/

4 Friese, S., Lin, V., Forry, N., & Tout, K. (2017). Defining and Measuring Access to High Quality Early Care and Education: A Guidebook for Policymakers and Researchers (No. 2017-08). Washington, DC: Office of Planning, Research and Evaluation. https://www.acf.hhs.gov/opre/report/defining-and-measuring-access-high-quality-early-care-and-education-ece-guidebook

5 U.S. Department of Health and Human Services Administration for Children and Families Child Care and Development Fund (CCDF). (2016). Federal Register. https://www.govinfo.gov/content/pkg/FR-2016-09-30/pdf/2016-22986.pdf

6 Fraga, L. M., Dobbins, D. R., Draper, F., & McCready, M. (2017). Parents and the High Cost of Child Care: 2017. Arlington, VA: Child Care Aware of America. https://usa.childcareaware.org/wp-content/uploads/2017/12/2017_CCA_High_Cost_Report_FINAL.pdf

7 Barnett, W. S., Carolan, M.E., Fitzgerald, J., & Squires, J.H. (2012). The State of Preschool 2012: State Preschool Yearbook. New Jersey: The National Institute for Early Education Research. http://nieer.org/state-preschool-yearbooks/the-state-of-preschool-2012

8 Johnson-Staub, C. (2017). Equity starts early: Addressing racial inequalities in child care and early education policy. Washington, DC: Center for Law and Social Policy. https://www.clasp.org/publications/report/brief/equity-starts-early-addressing-racial-inequities-child-care-and-early/

9 Council of Economic Advisers. (2015). The economics of early childhood investments. Washington, DC: The White House. https://obamawhitehouse.archives.gov/sites/default/files/docs/early_childhood_report_update_final_non-embargo.pdf

10 Laughlin, L. (2013). Who’s Minding the Kids? Child Care Arrangements: Spring 2011 (No. P70-135). Washington, DC: U.S. Census Bureau. https://www2.census.gov/library/publications/2013/demo/p70-135.pdf

11 Baldiga, M., Joshi, P., Hardy, E., & Acevedo-Garcia, D. (2018). Data-for-Equity Research Brief: Child Care Affordability for Working Parents. Waltham, MA: The Institute for Child, Youth and Family Policy. https://www.diversitydatakids.org/sites/default/files/2020-02/child-care_update.pdf

12 Corcoran, L., & Steinley, K. (2019). Early Childhood Program Participation, From National Household Education Surveys Program of 2016 (No. NCES 2017-101.REV). Washington, DC: National Center for Education Statistics, Institute of Education Sciences, U.S. Department of Education. https://nces.ed.gov/pubsearch/pubsinfo.asp?pubid=2017101REV

13 Mendez, J., Crosby, D. & Siskind, D. (2018). Access to Early Care and Education for Low-Income Hispanic Children and Families: A Research Synthesis. Bethesda, MD: National Research Center on Hispanic Children & Families.

https://hispanicrescen.wpengine.com/research-resources/access-to-early-care-and-education-for-low-income-hispanic-children-and-families-a-research-synthesis

14 Guzman, L., Hickman, S., Turner, K., & Gennetian, L. (2016). Hispanic children’s participation in early care and education: Perceptions of care arrangements, and relatives’ availability to provide care. Bethesda, MD: National Research Center on Hispanic Children & Families. https://hispanicrescen.wpengine.com/publications/hispanic-childrens-participation-in-early-care-and-education-parents-perceptions-of-care-arrangements-and-relatives-availability-to-provide-care/

15 López, M., Grindal, T., Zanoni, W., & Goerge, R. (2017). Hispanic children’s participation in early care and education: A look at utilization patterns of Chicago’s publicly funded programs. Bethesda, MD: National Research Center on Hispanic Children & Families. https://hispanicrescen.wpengine.com/publications/hispanic-childrens-participation-in-early-care-and-education-a-look-at-utilization-patterns-of-chicagos-publicly-funded-programs/

16 Li, W., Farkas, G., Duncan, G. J., Burchinal, M. R., & Vandell, D. L. (2013). Timing of high-quality child care and cognitive, language, and preacademic development. Developmental Psychology, 49(8), 1440-1451.

17 Walker, C., & Schmit, S. (2016). A Closer Look at Latino Access to Child Care Subsidies. Washington, DC: Center for Law and Social Policy. https://www.clasp.org/publications/report/brief/closer-look-latino-access-child-care-subsidies

18 Crosby, D., & Mendez, J. (2017). How common are nonstandard work schedules among low income Hispanic parents of young children? Bethesda, MD: National Research Center on Hispanic Children & Families. https://hispanicrescen.wpengine.com/publications/how-common-are-nonstandard-work-schedules-among-low-income-hispanic-parents-of-young-children/

19 Hill, Z., Gennetian, L., & Mendez, J. (2019). A descriptive profile of state Child Care and Development Fund policies in states with high populations of low-income Hispanic children. Early Childhood Research Quarterly, 47, 111-123.

20 Chaudry, A., Capps, R., Pedroza, J., Castaneda, R., Santos, R., & Scott, M. (2010). Facing Our Future: Children in the Aftermath of Immigration Enforcement. Washington, DC: The Urban Institute. https://www.urban.org/research/publication/facing-our-future

21 Matthews, H., Ulrich, R., & Cervantes, W. (2018). Immigration Policy’s Harmful Impacts on Early Care and Education. Center for Law and Social Policy: Washington, DC. https://www.clasp.org/publications/report/brief/immigration-policy-s-harmful-impacts-early-care-and-education

22 Barajas‐Gonzalez, R. G., Ayón, C., & Torres, F. (2018). Applying a community violence framework to understand the impact of immigration enforcement threat on Latino children. Social Policy Report, 31(3), 1-24.

23 National Survey of Early Care and Education Project Team. (2016). Early Care and Education Usage and Households’ Out-of-pocket

Costs: Tabulations from the National Survey of Early Care and Education (NSECE) (No. 2016-09). Washington, DC: Office of Planning, Research and Evaluation, Administration for Children and Families, U.S. Department of Health and Human Services. https://www.acf.hhs.gov/opre/resource/early-care-education-usage-households-out-of-pocket-costs-tabulations-nsece

24 Forry, N., Madill, R., & Halle, T. (2018). Snapshots from the NSECE: How Much Did Households in the United States Pay for Child Care in 2012? An Examination of Differences by Household Income (No. 2018-112). Washington, DC: Office of Planning, Research and Evaluation, Administration for Children and Families, U.S. Department of Health and Human Services. https://www.acf.hhs.gov/opre/resource/how-much-did-households-us-pay-child-care-in-2012-child-age-household-income-community-urbanicity-snapshots

25 Madill, R., Forry, N., & Halle, T. (2018). Snapshots from the NSECE: How Much Did Households in the United States Pay for Child Care in 2012? An Examination of Differences by Community Urbanicity (No. 2018-111). Washington, DC: Office of Planning, Research and Evaluation, Administration for Children and Families, U.S. Department of Health and Human Services. https://www.acf.hhs.gov/opre/resource/how-much-did-households-us-pay-child-care-in-2012-child-age-household-income-community-urbanicity-snapshots

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to thank the Steering Committee of the National Research Center on Hispanic Children & Families, Nicole Forry, and staff from OPRE for their feedback on earlier drafts of this brief, as well as Sara Dean and Deja Logan for their research assistance at multiple stages of this project.

Editor: Janet Callahan and Brent Franklin

Designer: Catherine Nichols

Copyright 2025 by the National Research Center on Hispanic Children & Families.

This website is supported by Grant Number 90PH0032 from the Office of Planning, Research & Evaluation within the Administration for Children and Families, a division of the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services totaling $7.84 million with 99 percentage funded by ACF/HHS and 1 percentage funded by non-government sources. Neither the Administration for Children and Families nor any of its components operate, control, are responsible for, or necessarily endorse this website (including, without limitation, its content, technical infrastructure, and policies, and any services or tools provided). The opinions, findings, conclusions, and recommendations expressed are those of the author(s) and do not necessarily reflect the views of the Administration for Children and Families and the Office of Planning, Research & Evaluation.