Insights From Hispanic Family Child Care Providers

Oct 1, 2025

Research Publication

Insights From Hispanic Family Child Care Providers

Author

Introduction

Home-based child care is the most prevalent type of nonparental child care in the United States. These care providers have long served an important role in supporting families, including many Hispanic families. Particularly for families with low incomes, home-based providers may offer more affordable and flexible care options for working parents than center-based programs.1,2 Further, given that home-based providers often live in the same communities as families—with whom they may have established relationships—this type of care may also align with parents’ preferences for familiarity and care that reflects their children’s cultural and language backgrounds.3,4

In 2019, among Hispanic households with low incomes, the vast majority (over 85%) of infants and toddlers in child care—and more than half (53%) of preschool-aged children in child care—were in home-based arrangements, either as their sole arrangement or in combination with center-based care.5 Home-based care options for families became even more critical during the COVID-19 pandemic, especially for frontline workers who continued to need safe and reliable care for their children.6 While more than 60 percent of center-based programs closed or reduced capacity during the early months of the pandemic, less than 30 percent of home-based programs did so.7 Compared to center-based providers, however, less is known about how home-based providers fared during this time as a key segment of the child care and early education (CCEE) workforce and as small business owners. Hispanic communities were disproportionately impacted by the pandemic, with comparatively high rates of COVID-19 infection, hospitalization, and death, and high levels of economic hardship.8 Hispanic home-based providers—who often primarily serve Hispanic families—may have acutely experienced the pandemic’s impacts in both their personal and professional lives.

This brief focuses on regulated home-based family child care (FCC) programs, as opposed to unregulated home-based providers; see “Home-based Care Context” for more information. Specifically, we examine how Hispanic FCC providers who cared for children in 2019 experienced the first year of the global COVID-19 pandemic. We draw on data from the National Survey of Early Care and Education (NSECE) COVID-19 Longitudinal Follow-Up Study (2020–2022), which followed child care providers from the 2019 NSECE to document their experiences during the pandemic. Our analysis focuses on Hispanic providers—who represented approximately 1 in 5 FCC providers nationally in 20199—and on those who were still operating during the first year of the COVID-19 pandemic. We consider provider well-being from a holistic lens,10 which includes physical health, mental health, and financial well-being, as well as exposure to potential stressors and access to supports. In particular, we examine the potential support that federal and state pandemic assistance provided to Hispanic FCC programs.

Key Findings

Most Hispanic family child care (FCC) providers operating during the first year of the COVID-19 pandemic demonstrated significant resilience by sustaining their small business despite financial hardships and exposure to health risks, by providing care for several key populations, and by expressing commitment to remain in the CCEE field in the future.

- Hispanic FCC providers were a stable and important source of child care for families during the COVID-19 pandemic.

- While many Hispanic FCC providers caring for children during the pandemic reported good physical and emotional health, we also found evidence of considerable exposure to health risks and experiences of financial hardship.

- Despite significant health risks and financial hardship, only 55 percent of Hispanic FCC providers serving children in early 2021 had received some form of federal or state pandemic assistance, and rates of receipt were under 30 percent for any one type of aid.

- We found few differences when comparing the characteristics and experiences of Hispanic FCC providers who did and did not receive federal or state relief funds during the first year of the pandemic. In one exception, providers who received pandemic assistance were more likely to be serving children and families with critical or high-priority care needs.

Additional context on home-based care

Home-based child care may be either unregulated or regulated. Unregulated home-based care providers—often referred to as family, friend, and neighbor (FFN) care—outnumber regulated home-based family child care (FCC) programs 10 to 1 nationally.11 However, the latter remain an important and relevant segment of the CCEE workforce. Home-based providers who participate in the regulatory system may gain benefits for themselves and the children and families they serve. For example, FCC programs are authorized to care for higher numbers of children than unlisted providers and are more likely to be eligible for professional and financial resources such as child care subsidies and technical assistance.12 Yet the number of home-based providers who seek out and successfully complete the licensing, certification, or registration process has declined since the early 2000s—potentially as a result of various disincentives and barriers that have been identified in the process.13,14 Research on the experiences of FCC providers and the resources that support their success can inform efforts to strengthen and grow this segment of the workforce.

Results

Characteristics and experiences of Hispanic FCC providers who cared for children during the first year of the COVID-19 pandemic

Nationally, 74 percent of regulated Hispanic FCC providers operating in 2019 were still open and caring for children in early 2021, roughly one year into the pandemic. With an average enrollment of just over eight children per provider, this population of more than 11,200 providers cared for more than 90,000 children during this time. The majority of these providers lived in urban communities with low to moderate poverty (49%) or high poverty (45%), with a much lower proportion located in more rural communities (6%) (Appendix Table A1).

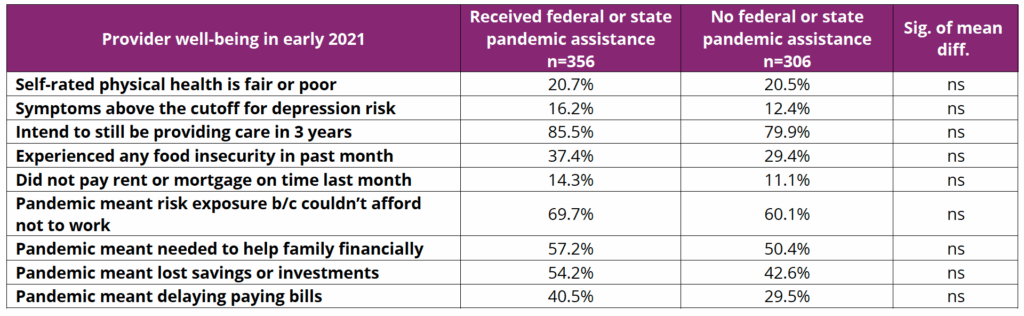

Hispanic FCC providers faced significant financial and employment challenges during the first year of the COVID-19 pandemic, despite continuing to support families and children through program closures. Most Hispanic FCC providers caring for children during the first year of the pandemic reported an annual household income below $60,000 and most (63%) were the primary earner in their family, with child care revenue contributing more than half of household income. Almost all providers (91%) reported spending personal funds on supplies for their business during the pandemic and most (77%) said it was harder to cover costs or remain open during this time. Roughly half of the Hispanic FCC providers still operating in early 2021 had had at least one unplanned closure of two weeks or more. During closures, most providers (62%) reported staying in contact with families, primarily to maintain relationships but also to support parents with instruction and engagement for children. Some Hispanic FCC providers began serving new groups of children during the pandemic, including children of essential workers (23%) and school-age children (20%). More than 80 percent of the providers expected to still be caring for children at least three years in the future (Figure 1).

Figure 1. More than 9 in 10 Hispanic FCC providers spent personal money on supplies during the pandemic and many reported food insufficiency, but most still expected to be providing care in 3 years.

Percentage of Hispanic FCC providers who spent personal funds on supplies since March 2020, who experienced food insecurity in the past month, and who intended to still be providing care in 3 years

Source:NSECE COVID-19 Longitudinal Follow-Up Home-Based Provider Survey public use data files

Source:NSECE COVID-19 Longitudinal Follow-Up Home-Based Provider Survey public use data filesNote:Unweighted sample sizes range from 623-666 depending on response rates to individual survey items. The NSECE COVID-19 Wave 1 home-based provider surveys were fielded from November 2020 to March 2021.

FCC: Family child care

Many Hispanic FCC providers rated their physical health as good and reported few depressive symptoms. The NSECE follow-up survey asked providers about several aspects of their well-being (Appendix Table A2). For this sample of Hispanic FCC providers caring for children in early 2021, we found that, on average, they rated their physical health as good and did not report high levels of depressive symptoms. A not-insignificant minority, however, described challenges to their well-being. Just over 10 percent reported depressive symptoms at a level consistent with clinical risk and just over 20 percent described their health as fair or poor. Further, roughly 40 percent of Hispanic FCC providers said that they or someone in their household had a health condition that put them at high risk of severe illness from COVID-19. By early 2021, nearly 1 in 4 Hispanic FCC providers reported at least one COVID-19 exposure within their program because of a diagnosed case among the children they served, themselves, or household members.

Many Hispanic FCC providers experienced financial challenges during the pandemic. Along with the sense that the pandemic had made it more difficult to cover business expenses (as reported above), two thirds (66%) said they felt unable to avoid working despite increased exposure to health risks (Figure 2, Appendix Table A2). Nearly half (49%) of the providers said the pandemic had led to lost savings or investments and more than one third (36%) reported delaying bills during this time, with just over 13 percent having missed a rent or mortgage payment. Additional evidence of providers’ challenges comes from the fact that one third (34%) said they had experienced food insecurity in the month prior to the survey (Figure 1, Appendix Table A2).

Figure 2. More than 6 in 10 Hispanic FCC providers said they had to risk COVID-19 exposure because they couldn’t afford not to work.

Percentage of Hispanic FCC providers who stated they felt unable to avoid working despite increased risk of exposure to health risks

Source: NSECE COVID-19 Longitudinal Follow-Up Home-Based Provider Survey public use data files

Source: NSECE COVID-19 Longitudinal Follow-Up Home-Based Provider Survey public use data filesNote: Unweighted sample sizes range from 623-666 depending on response rates to individual survey items. The NSECE COVID-19 Wave 1 home-based provider surveys were fielded from November 2020 to March 2021.

FCC: Family child care

Receipt of federal and state pandemic assistance among Hispanic listed home-based providers caring for children during the first year of the pandemic

During the initial year of the COVID-19 pandemic, significant federal funds were directed toward stabilizing the child care market and supporting families with young children. From March to December 2020, Congress allocated approximately $13 billion in child care relief funds to states through the Coronavirus Aid, Relief, and Economic Security (CARES) Act and the Coronavirus Response and Relief Supplemental Appropriations Act (CRRSA).a Many states chose to pay providers based on enrollment rather than attendance and ensure that they had the necessary PPE to safely care for children.

About half of all Hispanic FCC providers received at least some federal or state pandemic assistance in early 2021, despite limited receipt of support for any individual category. Just over half (55%) of the Hispanic FCC providers caring for children in early 2021 had received at least one form of federal or state pandemic assistance by that point, although any single type of assistance available that first year reached fewer than 1 in 3 Hispanic FCC providers (Figure 3, Appendix Table A3). Roughly 25 percent of Hispanic FCC providers received federal relief in the form of the Paycheck Protection Program (14%), a small business loan (13%), and/or an employee retention credit (2%). The most common type of assistance (received by 27% of Hispanic FCC providers) was state-funded essential supplies and PPE. Other forms of state assistance received by Hispanic FCC providers included retention grants (11%) and subsidies to care for children of essential workers (9%). For each specific type of federal or state assistance, less than 10 percent of respondents said they had applied and been denied, meaning that most Hispanic FCC providers who did not receive pandemic assistance did not apply for it.

Figure 3. More than half of all Hispanic FCC providers received some form of federal or state pandemic aid

Percentage of Hispanic FCC providers that received some form of federal or state pandemic aid

Source: NSECE COVID-19 Longitudinal Follow-Up Home-Based Provider Survey public use data files

Source: NSECE COVID-19 Longitudinal Follow-Up Home-Based Provider Survey public use data filesNote: Unweighted sample size = 662. a Captures whether provider reported receiving at least one of the types of federal or state assistance listed in the Table A3.

The NSECE COVID-19 Wave 1 home-based provider surveys were fielded from November 2020 to March 2021.

FCC: Family child care

Hispanic FCC providers who received federal or state relief funds during the first year of the COVID-19 pandemic differed from those who did not receive funds in several demographic and service characteristics. To learn more about the Hispanic FCC providers who successfully accessed government pandemic assistance, we compared characteristics of those who did and did not receive relief funds (Figure 4, Appendix Table A4). We found that those who received assistance by early 2021 were less likely to live in high-poverty urban communities and to speak Spanish as their primary language. They also had higher average household incomes and were more likely to report a high-risk health condition for themselves or a household member. Finally, drawing on data from the snapshot of care services provided in October 2020 (see textbox), we found that providers who received pandemic assistance were more likely to serve children whose care was subsidized with public CCEE dollars (i.e., child care subsidies, Head Start, or public pre-kindergarten) than providers who did not receive assistance. Because the survey item did not specify, it may be that these FCC providers received public funding themselves for the services they provided (e.g., child care subsidies, Early Head Start) or that they provided wrap-around care for children also being served by public CCEE programs like Head Start or state pre-Kindergarten.

Figure 4. Hispanic FCC providers who applied for and received pandemic assistance were less likely than those who did not to be in high-poverty urban communities and more likely to serve children connected to publicly funded child care and early education.

Characteristics of Hispanic family child care providers who did and did not receive federal or state relief funds during the first year of the COVID-19 pandemic

Source: NSECE COVID-19 Longitudinal Follow-Up Home-Based Provider Survey public use data files

Source: NSECE COVID-19 Longitudinal Follow-Up Home-Based Provider Survey public use data filesNote: Information about whether the provider was serving children receiving public CCEE funds was available only for the subsample who were open and caring for children during a focal week in October 2020 (n=394). The unweighted sample size for all other variables in the figure is 666. The NSECE COVID-19 Wave 1 home-based provider surveys were fielded from November 2020 to March 2021.

*p< .05 **p< .01 ***p< .001

CCEE: Child care and early education

FCC: Family child care

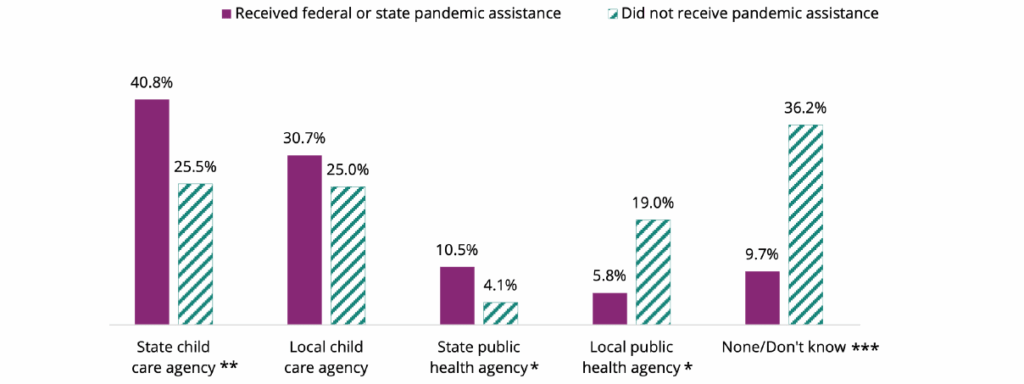

Compared to Hispanic FCC providers who received pandemic assistance, those who did not were less likely to name state agencies as key sources of information about applying for aid and more likely to say they had no information source. More than 40 percent of Hispanic FCC providers who received assistance identified state child care agencies as a key information source (compared to 25% who did not receive assistance) (Figure 5). State public health agencies were also mentioned more frequently by Hispanic FCC providers who received assistance (11% vs 4%). Providers who did and did not receive assistance were equally likely to say they had received information from their local child care agency, and those who did not receive assistance were more likely to identify their local public health agency as an information source (19% to 6%). Local public health agencies may have served as important resources to providers in sharing health practices and tracking community infection rates, but were perhaps less effective in connecting FCC providers to federal and state assistance available to child care providers and small business owners. Notably, more than 36 percent of Hispanic FCC providers who did not receive assistance in the first year of the pandemic said they had no information source or responded “don’t know,” compared to less than 10 percent of the providers who received assistance.

Figure 5. Hispanic FCC providers who did not receive early pandemic assistance were more likely than those who did to say they did not have an information source about aid

Key information sources about pandemic assistance for Hispanic family child care providers during the first year of the COVID-19 pandemic, by whether or not they applied for and received assistance

Source: NSECE COVID-19 Longitudinal Follow-Up Home-Based Provider Survey public use data files

Source: NSECE COVID-19 Longitudinal Follow-Up Home-Based Provider Survey public use data filesNote: Unweighted sample size = 662. The four most commonly identified sources of information among our sample of Hispanic FCC providers are shown in this figure. Other key sources of information mentioned by less than 10 percent of the sample (and not shown) include union representatives, local resource and referral agencies, other child care programs, coaches and trainers, federal child care agencies, national child care organizations, local school districts, word of mouth, news media, federal health agencies, and other non-specific government or nongovernment organizations. The NSECE COVID-19 Wave 1 home-based provider surveys were fielded from November 2020 to March 2021.

*p< .05 **p< .01 ***p< .001

CCEE: Child care and early education

FCC: Family child care

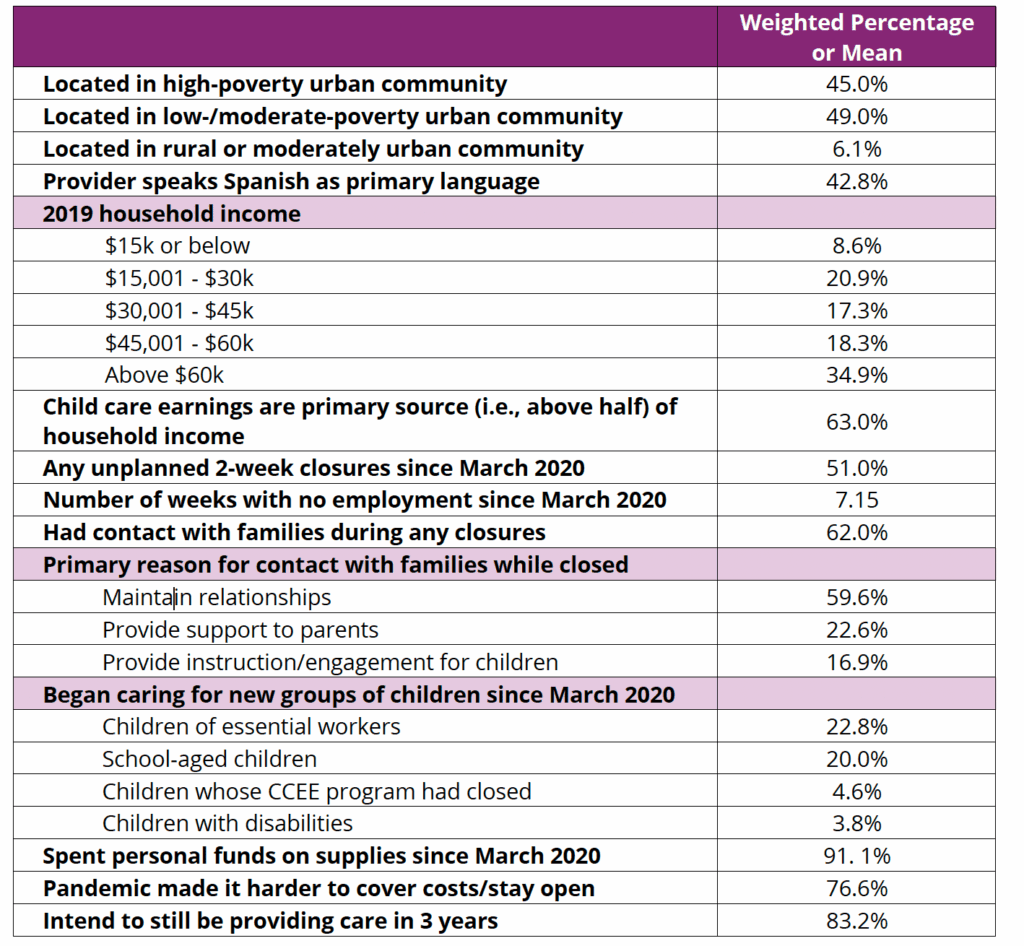

Hispanic FCC providers who received pandemic assistance reported similar levels of physical, emotional, and financial well-being as those who did not, but there were differences in their enrollment and the types of children they served. We also examined how Hispanic FCC providers who received pandemic assistance fared during the initial year of the pandemic compared to those who did not; we found few differences overall. In terms of well-being, Hispanic FCC providers who received federal or state pandemic assistance by early 2021 did not report statistically different levels of physical and emotional well-being or financial stress than providers who did not receive this type of assistance.

In terms of child care business operations, we found similar rates across the two groups for unplanned closures, duration of unemployment, having a COVID diagnosis in their program, spending personal funds for program operations, and difficulty covering operating costs during the pandemic (Figure 6, Appendix Table A4). One notable difference between Hispanic FCC providers who had and had not received pandemic relief by early 2021 was that the former reported higher rates of serving new groups of children after the onset of the pandemic. Providers receiving pandemic assistance were more likely to have begun caring for the children of essential workers, school-aged children, children with disabilities, and children whose CCEE program had closed. Providers receiving assistance were also more likely to have denied enrollment to families during the initial year of the pandemic because of limited capacity (45% vs. 27%).

Figure 6. Hispanic FCC providers who received federal or state pandemic assistance were more likely to have begun caring for children with critical or high-priority care needs.

Experiences of Hispanic family child care providers during the first year of the COVID-19 pandemic by whether they received federal or state pandemic assistance

Source: NSECE COVID-19 Longitudinal Follow-Up Home-Based Provider Survey public use data files

Source: NSECE COVID-19 Longitudinal Follow-Up Home-Based Provider Survey public use data filesNote: Unweighted sample sizes ranged from 625-652 depending on response rates for individual survey items. The NSECE COVID-19 Wave 1 home-based provider surveys were fielded from November 2020 to March 2021.

*p< .05 **p< .01 ***p< .001

CCEE: Child care and early education

FCC: Family child care

Enrollment and Care Services in Hispanic-Owned FCC Programs During the First Year of the Pandemic

The NSECE survey asked additional questions of family child care providers operating and caring for children during the last week of October 2020—about their enrollment and the services they had provided during that focal week. Approximately 400 Hispanic FCC owners (roughly 60% our analytic sample) cared for children during the focal week and received this section of the survey. We use these data to provide a snapshot of the children and families served by Hispanic FCC programs seven months into the pandemic.

Hispanic FCC providers cared for an average of eight children on a regular basis and most served a wide age range. That is, nearly all providers served infants/toddlers (93%) and preschool-aged children (89%), and more than 70 percent also enrolled school-aged children. A majority of these providers (84%) had at least one Hispanic child enrolled in their program and roughly two thirds (65%) served one or more dual language learner. Just over 20 percent served one or more children with a disability or chronic health need and 17 percent reported that one or more children in their care experienced food insecurity at home.

Table 1. Enrollment and care services provided by Hispanic FCC providers during a focal week in Oct 2020

Discussion

Considerable evidence suggests that working families benefit from home-based child care options being among the care arrangements they can choose from to meet their needs and preferences.15 Home-based providers often offer care that is affordable and flexible, covers hours when many center-based programs are not open, tends to be located within families’ communities, and features caregivers and educators who may share their home culture and language.4 During the COVID-19 pandemic, home-based providers offered critical care services at a time when many centers closed or had to reduce capacity. Evidence suggests that formal child care programs were particularly likely to close in high-Hispanic communities.16,17 At the same time, Hispanic parents are overrepresented in the types of essential and frontline jobs that continued during the pandemic.18

This brief offers a unique national snapshot of Hispanic family child care (FCC) providers’ experiences during the COVID-19 pandemic. We focused on this group of regulated providers as a policy-relevant segment of the CCEE workforce. Home-based child care programs that participate in state regulatory systems may gain benefits for both providers and families in terms of access to additional resources and professional development supports. However, the share of home-based providers connected with the regulatory system has declined over the past decade,9 raising questions about how this trend might be reversed. Our analysis highlights some of the strengths and contributions made by the Hispanic FCC home-based workforce and explores the role of federal and state resources in supporting their success.

Overall, we found that Hispanic FCC providers were a stable and important source of child care for families during the initial year of the COVID-19 pandemic and showed commitment to providing services to many children and families while balancing pandemic-related challenges like health risks, program closures, and financial strain. For example, more than 40 percent of these providers reported a high-risk health condition in their household and roughly one third experienced food insecurity and missed bill payments. Despite these challenges, the vast majority of Hispanic FCC providers operating in 2019 remained in business roughly one year into the pandemic, providing care for more than 90,000 children from birth through age 12; most of these providers signaled an intent to continue in the field for three or more years.

Several studies have demonstrated the critical role of federal and state relief funds in sustaining many child care programs and providers.19 This body of work also shows that center-based programs were more likely to access federal and state pandemic relief than home-based programs.6 Our findings suggest that Hispanic-owned FCC programs had especially low uptake of relief funds that may have been available to them, at least during the initial year of the pandemic. While just over half of the national population of FCC providers still operating in early 2021 said they had applied for and received at least one form of federal or state pandemic assistance, any specific type of aid reached fewer than 1 in 3 providers. The most common form of assistance, received by roughly one quarter of Hispanic FCC providers in our sample, was state-funded essential supplies or PPE. Having access to this important resource likely saved providers considerable money and time and helped them maintain safer care environments; PPE and other essentials were often scarce, difficult to find, and expensive.20 The generally low levels of assistance receipt among Hispanic FCC providers suggest missed opportunities for investment in an important workforce of caregivers and educators.

Our findings yield potential insights about which Hispanic FCC providers may have faced barriers to accessing needed support. Those who did not receive pandemic assistance during the first year—and, in most cases, this meant they did not apply for aid—were more likely to be in high-poverty urban communities (where need was arguably higher), to have low incomes themselves, and to speak Spanish as their primary language. Providers who did not receive assistance were also less likely than those who accessed aid to identify their state child care or public health agency as a key information source, and more likely to say they did not have any source of information about the availability of pandemic assistance. These results—along with the fact that FCC providers serving children with public CCEE funds had higher rates of assistance receipts—suggest that connections to public systems may have served as an important mechanism for connecting providers to financial supports during the COVID crisis. These providers may have had more familiarity and experience with completing necessary paperwork, as well as more access to the latest information from government agencies. In addition, many states used pandemic-era CCDF flexibilities to help CCEE programs serving children with subsidies stabilize their enrollment and funding.21

While Hispanic FCC providers’ well-being and business operations did not generally vary depending on their receipt of pandemic assistance, we found that those who received assistance were more likely to care for new groups of children during the pandemic, including the children of essential workers, school-age children, children with disabilities, and children whose CCEE program had closed—filling important gaps in care. This finding may represent an example of providers being responsive to federal and state efforts to build supply for underserved families and communities. For example, the availability of some types of assistance (e.g., increased reimbursement rates) to serve high-priority populations like children of essential workers and families receiving subsidies may have prompted or facilitated providers’ enrollment of these groups. Notably, nearly half of providers who received assistance reported turning away families because they had no available slots (compared to just over 25% of those who not receive assistance), highlighting the high demand for their services.

While our descriptive analysis provides a broad look at early pandemic experiences within the Hispanic FCC workforce at the national level, some areas of further study would be useful. An exploration of how Hispanic home-based providers’ care services, challenges, and access to supports vary across states and communities would shed light on different CCEE systems and variation in timing and intensity of pandemic impacts and state responses. The national estimate of a 6 percent decline in the number of licensed and license-exempt FCC homes from 2019 to 2022 obscures tremendous variation across states, some of which experienced growth in this sector.19 Accumulating evidence reveals significant variation in states’ allocation and distribution of the historic—but temporary—federal investments of $39 billion in child care that eventually became available in the later years of the pandemic (2021-2024) via the American Rescue Plan Act (ARPA).19 Nationally, more than 124,000 family child care homes received ARPA stabilization grants, with an average individual award of more than $30,000.22

Open questions remain regarding the extent to which critical relief and stabilization funds reached Hispanic FCC providers. The findings reported in this brief suggest that many of these licensed or registered providers did not apply for federal/state assistance despite high levels of financial need and exposure to risk and were not connected to information sources that could have helped them access available aid. Moving forward, continued research could illuminate how Hispanic home-based providers learn about—and can be encouraged or supported to engage with—regulatory systems in ways that benefit providers, children, families, and communities. Potential broad-based strategies that may benefit Hispanic providers include formalized family child care networks and regulatory processes that are streamlined, not overly burdensome, and accessible to a range of providers. In addition, it will be important to track the impact of the “funding cliff” created by the temporary nature of ARPA dollars and other pandemic-era CCEE investments on FCC providers, including Hispanic providers, who may face unique vulnerabilities relative to center-based programs. One assessment of center-based care suggests that the loss of ARPA funds has led to increased care costs for families and staff shortages for programs, even in states that have increased their CCEE investments.23

Methods

The National Survey of Early Care and Education (NSECE) studies, first launched in 2012, have offered a unique opportunity to learn more about the national home-based child care and early education (CCEE) workforce, which is often absent from other large-scale child care datasets. In this brief, we use publicly available data from the NSECE COVID-19 Longitudinal Follow-Up study (NSECE Project Team, 2023) to examine the experiences and outcomes of listed Hispanic family child care (FCC) providers. The NSECE studies also include unlisted home-based providersb; however, very small sample sizes in the COVID-19 Longitudinal Follow-Up did not allow for an analysis of that group.

While the 2012 and 2019 data collections were cross-sectional, the NSECE COVID-19 Longitudinal Follow-Up survey was designed to capture timely information about the status and well-being of the 2019 CCEE workforce after the onset of the global pandemic.

Just over 1,000 Hispanic FCC providers—representing a population of more than 16,600 providers nationally—were in the 2019 NSECE sample. Of these, 815 providers were successfully recruited to participate in the Wave 1 NSECE COVID-19 follow-up survey. Within this group, our primary analytic sample consists of the 666 Hispanic FCC providers who were caring for children at the time of the Wave 1 survey. We focused on this group because they received all sections of the survey; providers not caring for children at the time of the Wave 1 survey were not asked about their care services during the pandemic or receipt of any pandemic assistance. Based on mean comparisons between the full sample and our analytic subsample, we found that providers included in the analyses for this brief had higher household incomes and were more likely to be the primary earner in their household and to say they kept working during the pandemic for financial reasons and to help their family. Providers in our analytic sample also rated themselves in better physical health and were more likely to expect to still be in the field in three years.

The Wave 1 provider surveys were fielded from November 2020 to March 2021. Within our Hispanic sample, most surveys were completed in January and February 2021, with fewer completed in December 2020 and March 2021. In the brief, we broadly characterize this time period of data collection as the first year of the pandemic.

Descriptive statistics were calculated with NSECE survey weights applied to adjust for the complex sampling design and non-response. Analyses were conducted using Stata 18. Paired sample t-tests were used to compare those who were included versus excluded in the primary analytic sample and to compare the experiences and outcomes of providers who did and did not receive federal or state pandemic assistance from March 2020 to March 2021.

Footnotes

a The data analyzed in this brief were collected prior to the enactment of the American Rescue Plan Act (ARPA) in March 2021, which authorized an additional $39 billion for the child care sector, representing the largest pandemic-era investment.

b Unlisted home-based providers are not registered on publicly available child care lists and often include family, friends, and neighbors. Listed home-based providers are registered on publicly available lists as meeting state regulations and may be licensed or license-exempt.

Suggested Citation

Crosby, D., Omondi, F., Wrather, A., Mendez, J., & Jacome Ceron, A. (2025). Insights from Hispanic family child care providers. National Research Center on Hispanic Children & Families. https://doi.org/10.59377/730c8641r

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to thank the Steering Committee of the National Research Center on Hispanic Children & Families—along with Kristen Harper and Laura Ramirez—for their helpful comments, edits, and research assistance at multiple stages of this project. The Center’s Steering Committee is made up of the Center investigators—Drs. Natasha Cabrera (University of Maryland, co-PI), Danielle Crosby (University of North Carolina at Greensboro, co-PI), Lisa Gennetian (Duke University, co-PI), Lina Guzman (Child Trends, PI), Doré LaForett (Child Trends, co-I), Julie Mendez (University of North Carolina at Greensboro, co-PI), and Maria Ramos-Olazagasti (Child Trends, deputy director and co-PI)—and federal project officers Drs. Jenessa Malin and Kimberly Clum (Office of Planning, Research and Evaluation).

This product is supported by Grant Number 90PH0032 from the Office of Planning, Research & Evaluation within the Administration for Children and Families, a division of the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services totaling $7.84 million with 99 percentage funded by ACF/HHS and 1 percentage funded by non-government sources. Neither the Administration for Children and Families nor any of its components operate, control, are responsible for, or necessarily endorse this product. The opinions, findings, conclusions, and recommendations expressed are those of the author(s) and do not necessarily reflect the views of the Administration for Children and Families and the Office of Planning, Research & Evaluation. For more information, please visit the ACF website, Administrative and National Policy Requirement.

Editor: Brent Franklin

Designers: Joseph Boven and Krystal Figueroa

About the Authors

Danielle A. Crosby, PhD, is a co-principal investigator of the National Research Center on Hispanic Children & Families, co-leading the research area on early care and education. She is an associate professor in the Department of Human Development and Family Studies at the University of North Carolina at Greensboro. Her research focuses on understanding how policies and systems shape early education access and quality for young children in low-income families.

Favour Omondi, MS, is a doctoral student in the Human Development and Family Studies department at the University of North Carolina at Greensboro. She recently completed her Master’s degree in the same program. Her research interests focus on the multi-level factors that place young children at risk for maltreatment and the role of protective mechanisms (including access to high-quality early childhood education) in mitigating these risks.

Amy Wrather, MS, is a doctoral student in the Human Development and Family Studies department at the University of North Carolina at Greensboro. She recently completed her Master’s degree in the same program. Her research interests focus on promoting high-quality learning environments for young children with disabilities across traditional and alternative models of early childhood education.

Julia Mendez, PhD, is a co-principal investigator of the National Research Center on Hispanic Children & Families, co-leading the research area on early care and education. She is a professor in the Department of Psychology at the University of North Carolina at Greensboro. Her research focuses on risk and resilience among low-income and Latino children and families, with an emphasis on parent-child interactions and family engagement in early care and education programs.

Anyela Jacome Ceron, MPS, is a graduate student in a Clinical Psychology program at the University of North Carolina at Greensboro. She received her Master’s degree from the University of Maryland, College Park in Clinical Psychological Science. Her research interests focus on the well-being of children and families and understanding risk and protective factors in the context of culture. She also has interests in family engagement in early care and education programs.

About the Center

The National Research Center on Hispanic Children & Families (Center) conducts research to inform programs and policy to better serve Hispanic children and families with low incomes. Our research focuses on poverty reduction and economic self-sufficiency; child care and early education, including federal programs such as Head Start (HS) and the Child Care and Development Fund (CCDF); and cross-cutting topics that include parenting, family structure, and family dynamics. The Center is led by Child Trends, in partnership with Duke University, University of North Carolina at Greensboro, and University of Maryland, College Park.

Copyright 2025 by the National Research Center on Hispanic Children & Families.

Appendix

Table A1. Child care operations among Hispanic family child care providers caring for children roughly one year into the COVID-19 pandemic

Source: NSECE COVID-19 Longitudinal Follow-Up Home-Based Provider Survey public use data files

Source: NSECE COVID-19 Longitudinal Follow-Up Home-Based Provider Survey public use data filesNote: Unweighted sample sizes range from 623-666 depending on response rates to individual survey items. The NSECE COVID-19 Wave 1 home-based provider surveys were fielded from November 2020 to March 2021.

CCEE: Child care and early education

FCC: Family child care

Table A2. Health and well-being of Hispanic family child care providers caring for children roughly one year into the COVID-19 pandemic

Source: NSECE COVID-19 Longitudinal Follow-Up Home-Based Provider Survey public use data files

Source: NSECE COVID-19 Longitudinal Follow-Up Home-Based Provider Survey public use data filesNote: Unweighted sample sizes range from 623-666 depending on response rates to individual survey items. The NSECE COVID-19 Wave 1 home-based provider surveys were fielded from November 2020 to March 2021.

FCC: Family child care

Table A3. Types of federal and state pandemic assistance received by Hispanic FCC providers by early 2021

Source: NSECE COVID-19 Longitudinal Follow-Up Home-Based Provider Survey public use data files

Source: NSECE COVID-19 Longitudinal Follow-Up Home-Based Provider Survey public use data filesNote: Unweighted sample size = 662. a Captures whether provider reported receiving at least one of the types of federal or state assistance listed in the table. The NSECE COVID-19 Wave 1 home-based provider surveys were fielded from November 2020 to March 2021.

FCC: Family child care

Table A4.Comparisons between Hispanic FCC providers who did and did not receive federal or state pandemic assistance during the initial year of the COVID-19 pandemic

Source: NSECE COVID-19 Longitudinal Follow-Up Home-Based Provider Survey public use data files.

Source: NSECE COVID-19 Longitudinal Follow-Up Home-Based Provider Survey public use data files.Note: *p< .05 **p< .01 ***p< .001

FCC: Family child care

ECE: Early care and education

Table A5. Physical, emotional, and financial well-being of Hispanic family child care providers by receipt of federal or state pandemic assistance during initial year of COVID-19 pandemic

References

References

1 Adams, G., & Dwyer, K. (2021). Expanding subsidies for home-based child care providers could aid the post-pandemic economic recovery. Urban Institute. https://www.urban.org/urban-wire/expanding-subsidies-home-based-child-care-providers-could-aid-postpandemic-economic-recovery

2 Adams, G., & Dwyer, K. (2023). The Small Business Administration and home-based child care providers: Expanding participation. Urban Institute. https://www.urban.org/research/publication/small-business-administration-and-home-based-child-care-providers-expanding-participation

3 Coleman-Castillo, K. (2024). Connection & community: Elevating the impact of Latina early educators. National Women’s Law Center. https://nwlc.org/resource/connection-community-elevating-the-impact-of-latina-early-educators/

4 Hill, Z., Yadatsu Ekyalongo, Y., Paschall, K., Madill, R., & Halle, T. (2021, May). A demographic comparison of the listed home-based early care and education workforce and the children in their care (OPRE Report No. 2020-128). Office of Planning, Research, and Evaluation, Administration for Children and Families, U.S. Department of Health and Human Services.

5 Mendez, J., Crosby, D., & Stephens, C. (2024). Nearly half of Hispanic children in households with low incomes used early care and education in 2019. National Research Center on Hispanic Children and Families. https://doi.org/10.59377/349u4419b

6 Porter, T., Bromer, J., Melvin, S., Ragonese-Barnes, M., & Molloy, P. (2020). Family child care providers: Unsung heroes in the COVID-19 crisis. Herr Research Center, Erikson Institute. https://www.erikson.edu/wp-content/uploads/2020/09/Family-Child-Care-Providers_Unsung-Heroes-in-the-COVID-19-Crisis.pdf

7 Lin, Y., & McDoniel, M. (2023, August). Understanding child care and early education program closures and enrollment during the first year of the COVID-19 pandemic (OPRE Report #2023-237). Office of Planning, Research and Evaluation, Administration for Children and Families, U.S. Department of Health and Human Services. https://acf.gov/opre/report/understanding-child-care-and-early-education-program-closures-and-enrollment-during

8 Noe-Bustamante L., Krogstad J.M., & Lopez M.H. (July 15, 2021). For US. Latinos, COVID-19 Has Taken a Personal and Financial Toll. Pew Research Center. https://www.pewresearch.org/race-ethnicity/2021/07/15/for-u-s-latinos-covid-19-has-taken-a-personal-and-financial-toll/

9 Crosby, D. A., Mendez, J., & Stephens, C. (2023). Characteristics of the early childhood workforce serving Latino children. National Research Center on Hispanic Children and Families. https://www.hispanicresearchcenter.org/research-resources/characteristics-of-the-early-childhood-workforce-serving-latino-children/

10 Warner, M., & Davis Schoch, A. (2024). Aspects of well-being for the child care and early education workforce (OPRE Report No. 2023-339). Office of Planning, Research and Evaluation, Administration for Children and Families, U.S. Department of Health and Human Services

11 Datta, A. R., Milesi, C., Srivastava, S., & Zapata-Gietl, C. (2021). NSECE chartbook – Home-based early care and education providers in 2012 and 2019: Counts and characteristics (OPRE Report No. 2021-85). Office of Planning, Research and Evaluation, Administration for Children and Families, U.S. Department of Health and Human Services. https://acf.gov/opre/report/home-based-early-care-and-education-providers-2012-and-2019-counts-and-characteristics

12 Kane, M. C., Harris, P., Jordan, D., Lloyd, C. M., & Salomone Testa, M. B. (2021, January). Promising practices in policy for home-based child care: A national policy scan. Home Grown Child Care. Retrieved from https://homegrownchildcare.org/wp-content/uploads/2021/01/FCC-policy-scan-10.29-1.pdf

13 Bromer, J., Porter, T., Melvin, S., & Ragonese-Barnes, M. (2021). Family Child Care Educators’ Perspectives on Leaving, Staying, and Entering the Field: Findings from the Multi-State Study of Family Child Care Decline and Supply. Herr Research Center, Erikson Institute. https://www.erikson.edu/wp-content/uploads/2021/11/FCD_DeclineStudy_2021.pdf

14 Hallam, R., Hooper, A., Bargreen, K., Buell, M., & Han, M. (2017). A two-state study of family child care engagement in quality rating and improvement systems: A mixed-methods analysis. Early Education and Development, 28(6), 669–683. https://doi.org/10.1080/10409289.2017.1303306

15 Mendez, J., & Crosby, D. A. (2024). Reflections on a decade of research on early childhood education access for Latino families with low incomes. National Research Center on Hispanic Children & Families. DOI: http://doi.org/10.59377/994e1263e

16 Lee, E. K., & Parolin, Z. (2021). The care burden during COVID-19: A national database of child care closures in the United States. Socius, 7, 1-10. https://doi.org/10.1177/23780231211032028

17 Zhang, Q., Sauval, M., Jenkins, J. M. (2023). Impacts of the COVID-19 pandemic on the child care sector: Evidence from North Carolina. Early Child Research Quarterly, 62, 17-30. DOI: 10.1016/j.ecresq.2022.07.003

18 Centers for Disease Control (Dec. 10, 2020). COVID-19 Racial and Ethnic Health Disparities.

19 King, C., Banghart, P., Hackett, S., Guerra, G., & Appel, S. (2024). Future directions for child care stabilization: Insights from state and territory uses of COVID-19 relief funds. Child Trends. DOI: 10.56417/1169b4422y

20 Kim, Y., Montoya, E., Doocy, S., Austin, L., & Whitebook, M. (2022). Impacts of COVID-19 on the early care and education sector in California: Variations across program types. Early Childhood Research Quarterly, 60, 348-362.

21 Office of Inspector General. (2020). National snapshot of state agency approaches to child care during the COVID-19 pandemic.

22 U.S. Department of Health and Human Services. (2023). ARPA Child Care Stabilization Funding State and Territory Fact Sheet. Administration for Children and Families, Office of Child Care. https://acf.gov/sites/default/files/documents/occ/National_ARP_Child_Care_Stabilization_Fact_Sheet.pdf

23 Kashen, J. & Valle-Guiterrez, L. (2024). Child Care Funding Cliff at One Year: Rising Prices, Shrinking Options, and Families Squeezed. The Century Foundation. https://tcf.org/content/report/child-care-funding-cliff-at-one-year/

Copyright 2025 by the National Research Center on Hispanic Children & Families.

This website is supported by Grant Number 90PH0032 from the Office of Planning, Research & Evaluation within the Administration for Children and Families, a division of the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services totaling $7.84 million with 99 percentage funded by ACF/HHS and 1 percentage funded by non-government sources. Neither the Administration for Children and Families nor any of its components operate, control, are responsible for, or necessarily endorse this website (including, without limitation, its content, technical infrastructure, and policies, and any services or tools provided). The opinions, findings, conclusions, and recommendations expressed are those of the author(s) and do not necessarily reflect the views of the Administration for Children and Families and the Office of Planning, Research & Evaluation.