Informal and Formal Supports May Affect Hispanic Early Educators’ Physical and Mental Well-Being

Aug 12, 2024

Research Publication, Research Series

Informal and Formal Supports May Affect Hispanic Early Educators’ Physical and Mental Well-Being

Author

An earlier version of this document’s citations were misnumbered. This document’s citations were updated on 8/12/2024.

Introduction

Ensuring the well-being of the early care and education (ECE) workforce is essential to providing high-quality care to young children enrolled in ECE programs. Teachers’a well-being can contribute to the quality of their interactions with children and to children’s outcomes: Children whose teachers are sensitive, warm, and nurturing show greater cognitive and social competence than children whose teachers do not possess these qualities.1 Unfortunately, a range of factors—including a shortage of qualified teachers due to the COVID-19 pandemic—have made it more difficult to locate, support, and retain a talented and healthy ECE workforce.

Increasingly, formal and informal supports such as a positive ECE program climate, retirement, and other benefits are seen as an important part of supporting the ECE workforce. Further, understanding the reasons why Latino ECE providers care for children and the ways that informal and formal supports contribute to their well-being are important goals for ECE research and policy to inform efforts to retain and promote ECE providers.

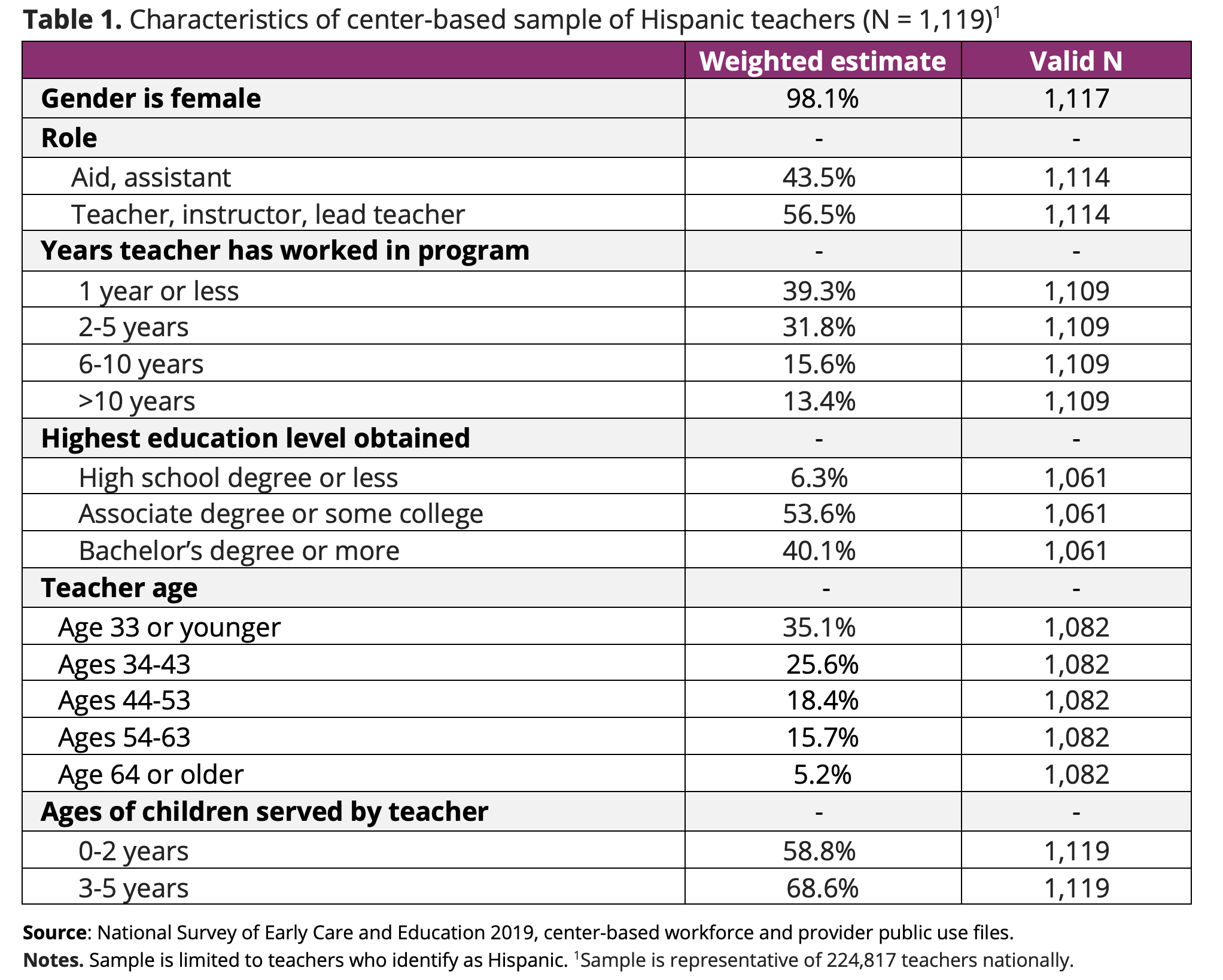

This brief draws on a nationally representative sample from the National Study for Early Care and Education (NSECE) 2019, inclusive of more than 1,100 Latinob educators in the center-based ECE workforce—or about 17 percent of all ECE workers (the weighted workforce sample for children from birth to age 5).c Retention of Latinos in the workforce has multiple benefits for Latine children and families, including access to professionals who are likely to speak Spanish and share the children’s culture. Moreover, families may seek out Latine providers to ensure their children receive culturally and linguistically competent services. This is critically important, as Latino children comprise large numbers of children enrolled in ECE programs, particularly in high-Hispanic -serving states such as Texas, California, and Florida (among others).2

Prior work using NSECE 2012 data found that several informal workforce supports significantly predicted lower levels of teachers’ psychological distress.3 Specifically, after controlling for a variety of background factors, teachers who felt that teamwork was encouraged in their program and those who reported feeling respected in their centers had significantly lower levels of distress than those who did not perceive a level of teamwork or respect.3 We seek to extend these findings by exploring how informal supports are related to Hispanic teachers’ distress, but also to their physical health.

- Physical health

- Depressive symptoms

- Engagement in meaningful work

This brief aims to improve our understanding of the well-being of the Hispanic ECE workforce and how ECE programs may play a role in their well-being (or “wellness”). Staff wellness is a term that refers to ECE educators’ mental and physical health and how such health “shapes their engagement, job satisfaction, and overall quality of life.”4 We take a broad view of Latino provider well-being by examining three indicators: providers’ physical health, depressive symptoms, and engagement in meaningful work—defined as their purpose or reasons for their work in child care.

We first describe how the Latine ECE workforce is faring across those indicators and explore the extent to which members of the Latine ECE workforce are considering leaving their positions, and the reasons why. Because available workforce supports, both informal and formal, can shape ECE educators’ physical health and distress, we also examine how such supports relate to teacher’s depressive symptoms and physical health. Informal supports may include respect for teachers and a culture of teamwork and collaboration; formal supports may include health insurance and other benefits.

Key Findings

- Most Hispanic center-based teachers in this sample reported being in good (53%) or excellent (33%) physical health. A small share reported fair (13%) or poor (1%) health.

- Overall rates of depressive symptoms are low among Hispanic teachers: 12 percent reported feeling some depressive symptoms in the last week and 8 percent reported symptoms at a level indicating risk for clinical depression.

- The reasons cited by the most Hispanic teachers as to why they work with young children were it’s “a personal calling” (34%), “it’s my career or profession” (24%), and “a way to help children” (22%).

- However, one in four Hispanic ECE providers reported looking for new or additional work in the past three months. The most common reasons provided were to “find a job that pays more” (54%), “to find a second job” (10%), and “to find advancement in the child care field” (10%).

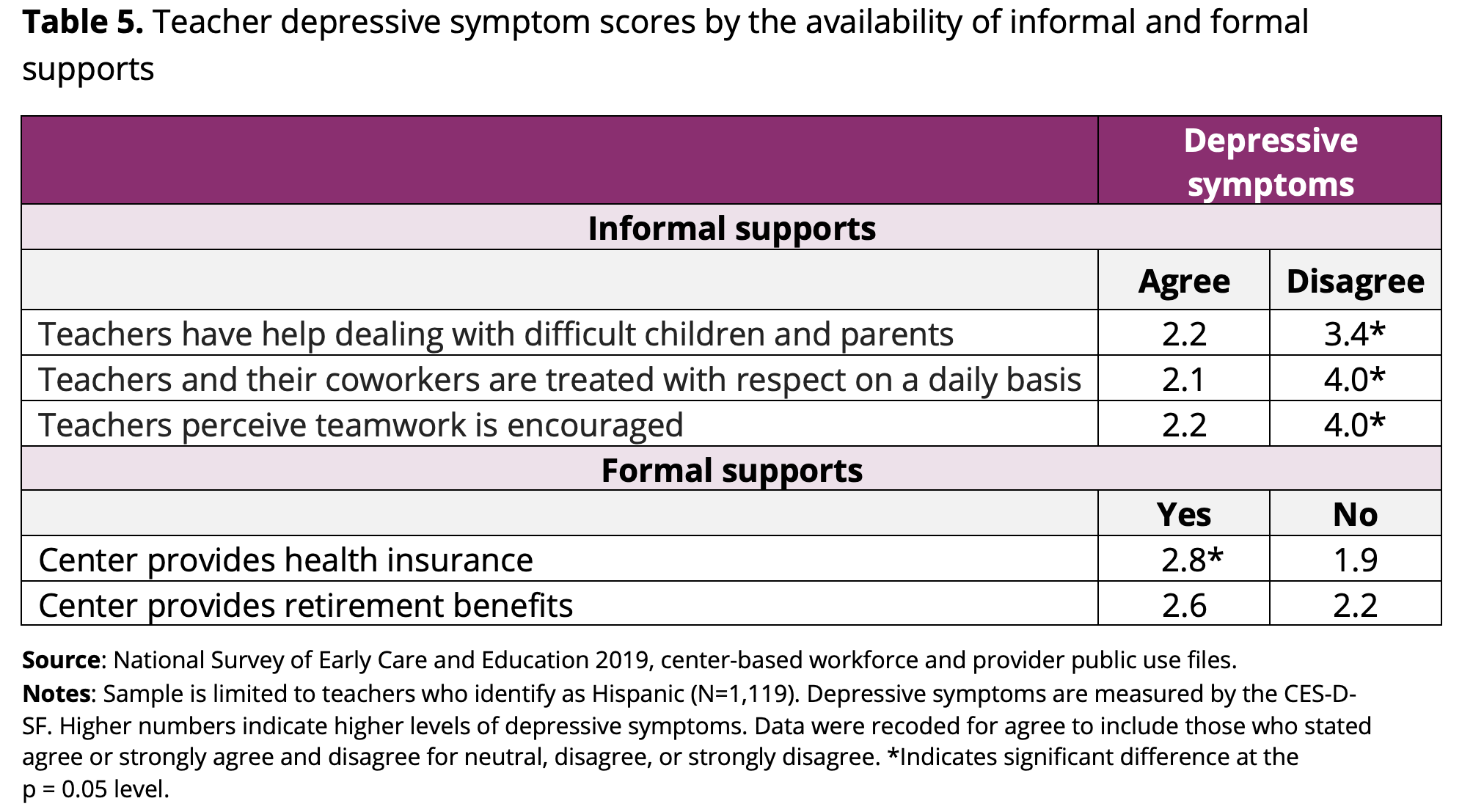

- Providers’ symptoms of depression were related to informal and formal supports within ECE programs.

- Higher depressive symptoms were observed among workforce members who perceived less informal support from their programs—specifically respect, teamwork, and help working with children or their parents who they perceive to be difficult—compared to those with adequate levels of informal support.

- Teachers working in centers that provide health insurance had higher than average depressive symptoms than those in centers that did not provide this benefit.

Collectively, these results document relatively strong physical and mental health among the Hispanic ECE workforce, with meaningful intentions among providers to contribute to children’s well-being or to have a career in early care and education. At the same time, we found evidence of significant concern among Latine educators regarding the pay associated with their positions. About one quarter of providers reported looking for other or additional work, with over half being motivated by finding a job that pays more. Additionally, we found that informal supports, such as fostering respect and teamwork within programs, do matter. Programs should consider how these issues can be addressed within programs to create a more positive work climate for the Latino ECE workforce.

Results

Physical health and depression symptoms among the Hispanic ECE workforce

As shown in “Educators’ health” (Figure 1), 33 percent of the Hispanic ECE workforce described their overall physical health as excellent, 53 percent reported good health, 13 percent indicated fair health, and less than 1 percent reported having poor health.

Figure 1: Most Hispanic educators reported being in good or excellent health

Percentage of Hispanic ECE teachers indicating they were in excellent, good, fair, or poor health, 2019  Figure 2 shows how often educators indicated feeling depressed during the past week. Over 85 percent indicated feeling depressed rarely or none of the time (less than one day), 7 percent reported depressive symptoms some or little of the time (one to two days), 4 percent reported a moderate amount of the time, and less than 1 percent indicated all of the time. Additionally, the Center for Epidemiological Studies-Depression–short form (CES-D-SF)—a multi-item measure used to assess depressive symptoms—identified that 8 percent of Hispanic teachers had depression scores at the clinical cutoff, indicated by a score of 8 or more. Overall, we find a small—but consequential—number of Hispanic ECE teachers at risk of experiencing clinical levels of depression.

Figure 2 shows how often educators indicated feeling depressed during the past week. Over 85 percent indicated feeling depressed rarely or none of the time (less than one day), 7 percent reported depressive symptoms some or little of the time (one to two days), 4 percent reported a moderate amount of the time, and less than 1 percent indicated all of the time. Additionally, the Center for Epidemiological Studies-Depression–short form (CES-D-SF)—a multi-item measure used to assess depressive symptoms—identified that 8 percent of Hispanic teachers had depression scores at the clinical cutoff, indicated by a score of 8 or more. Overall, we find a small—but consequential—number of Hispanic ECE teachers at risk of experiencing clinical levels of depression.

Figure 2: About 1 in 10 Hispanic educators reported experiences of depressive symptoms during the past week

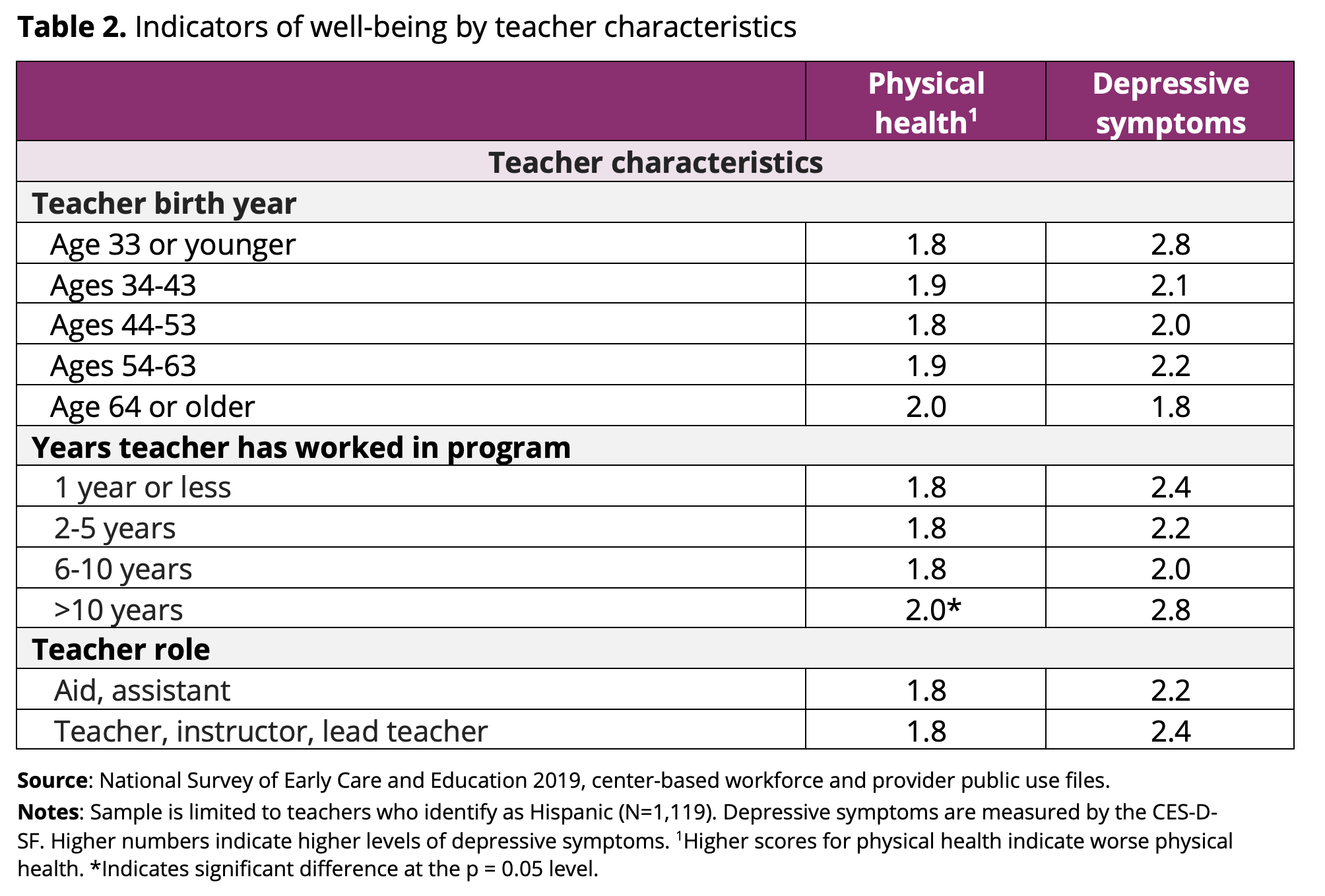

Percentage of Hispanic ECE educators who reported depressive symptoms, by frequency of symptoms, 2019 Teachers’ well-being can vary according to personal characteristics such as age, years of experience, and role (assistant or lead). Thus, we explored whether two indicators of teacher well-being—physical health and depressive symptoms—varied according to teacher characteristics (Table 2). Results suggested that teachers with 10 or more years of experience in their program reported worse ratings of their physical health, relative to teachers with fewer years of experience. We observed no significant differences between teacher depressive symptom scores and years of experience. Additionally, we found no significant differences in teacher physical health or depressive symptoms by age, years of experience, or by role (lead/assistant).

Teachers’ well-being can vary according to personal characteristics such as age, years of experience, and role (assistant or lead). Thus, we explored whether two indicators of teacher well-being—physical health and depressive symptoms—varied according to teacher characteristics (Table 2). Results suggested that teachers with 10 or more years of experience in their program reported worse ratings of their physical health, relative to teachers with fewer years of experience. We observed no significant differences between teacher depressive symptom scores and years of experience. Additionally, we found no significant differences in teacher physical health or depressive symptoms by age, years of experience, or by role (lead/assistant).

Feelings of meaningful work among the Hispanic ECE workforce

The NSECE asked Hispanic educators about their main reasons for working with young children (Figure 3). More than one third (35%) indicated that working with young children is a personal calling. This was followed by 24 percent who indicated that ECE is their career/profession, 22 percent reporting that their job is a way to help children, and 13 percent indicating that it is a step toward a related career. Notably, a significantly smaller share of teachers indicated that they are motivated by a paycheck (3%), by work they can do while their children are young (2%), or by helping parents (<1%); very few did not relate to any of the reasons listed (1%).

Figure 3: 1 in 3 Hispanic ECE workforce participants reported work with young children as a personal calling

Teachers’ responses to reasons for working with young children, 2019 Desire to find new or additional work

Desire to find new or additional work

Staff who feel their work is meaningful and rewarding tend to feel more committed to their work,5 and understanding why Hispanic teachers may look for work outside of their current positions is of crucial importance for identifying factors related to retention. In this study, Hispanic teachers were asked about their intentions to stay in the profession—and specifically, whether they have looked for a new job or additional employment in the past three months. Findings indicate that one quarter of the sample indicated ‘yes’—meaning they have looked for additional or new employment. Among this share of Hispanic teachers who had looked for work, more than half (54%) indicated finding a job that pays more as a reason for their search.

Other reasons cited for seeking new/additional work included finding a job for professional growth or advancement within the child care field (10%), finding a second job (10%), finding improved work conditions in the program (5%), seeing what other opportunities are available (5%), reducing their commute or improving their schedule (4%), worrying that their current job may end (3%), and wanting to leave the field (2%). Less common reasons included finding a job with a better fit (2%), having more work hours (2%), finding summer employment (1%), obtaining a job with benefits (<1%), and finding a job due to relocation (<1%).

Hispanic Educators’ Access to Informal and Formal Supports That May Promote Well-Being

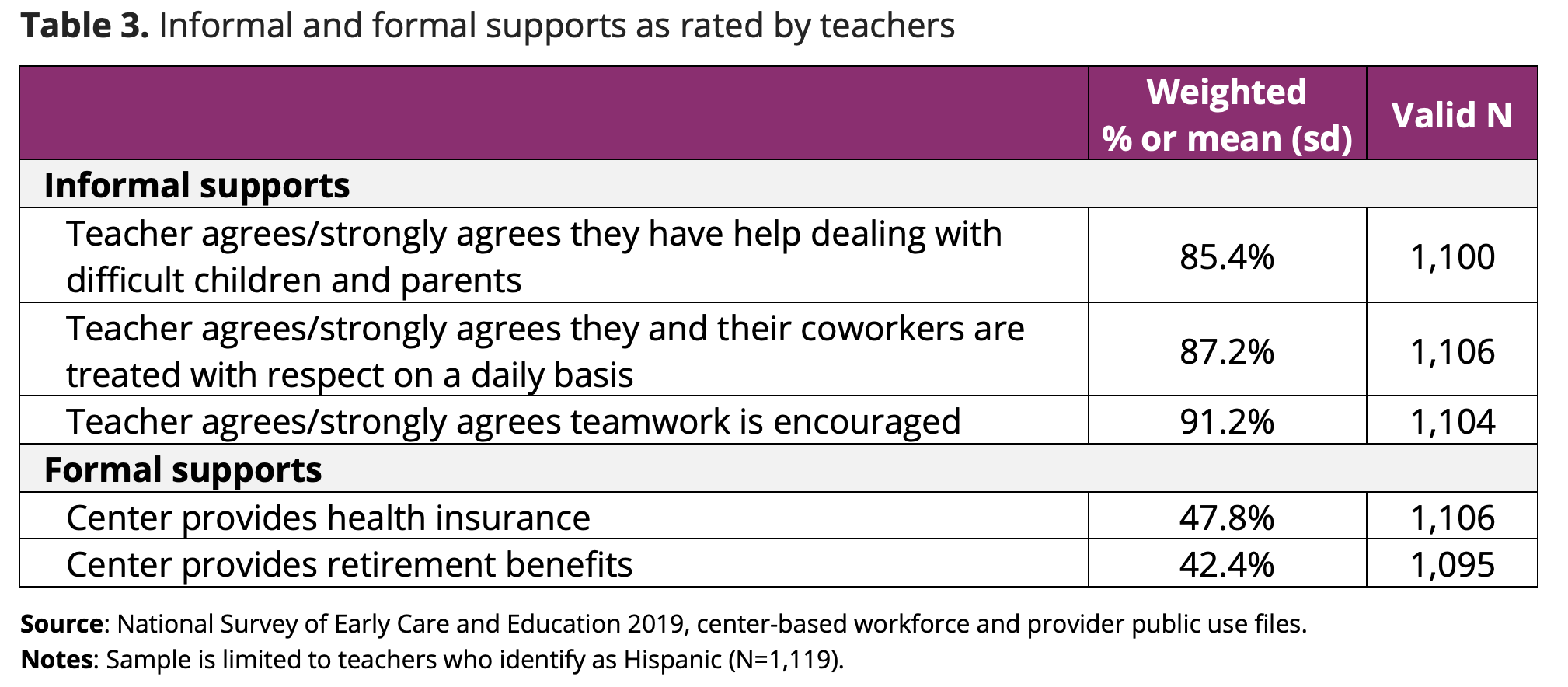

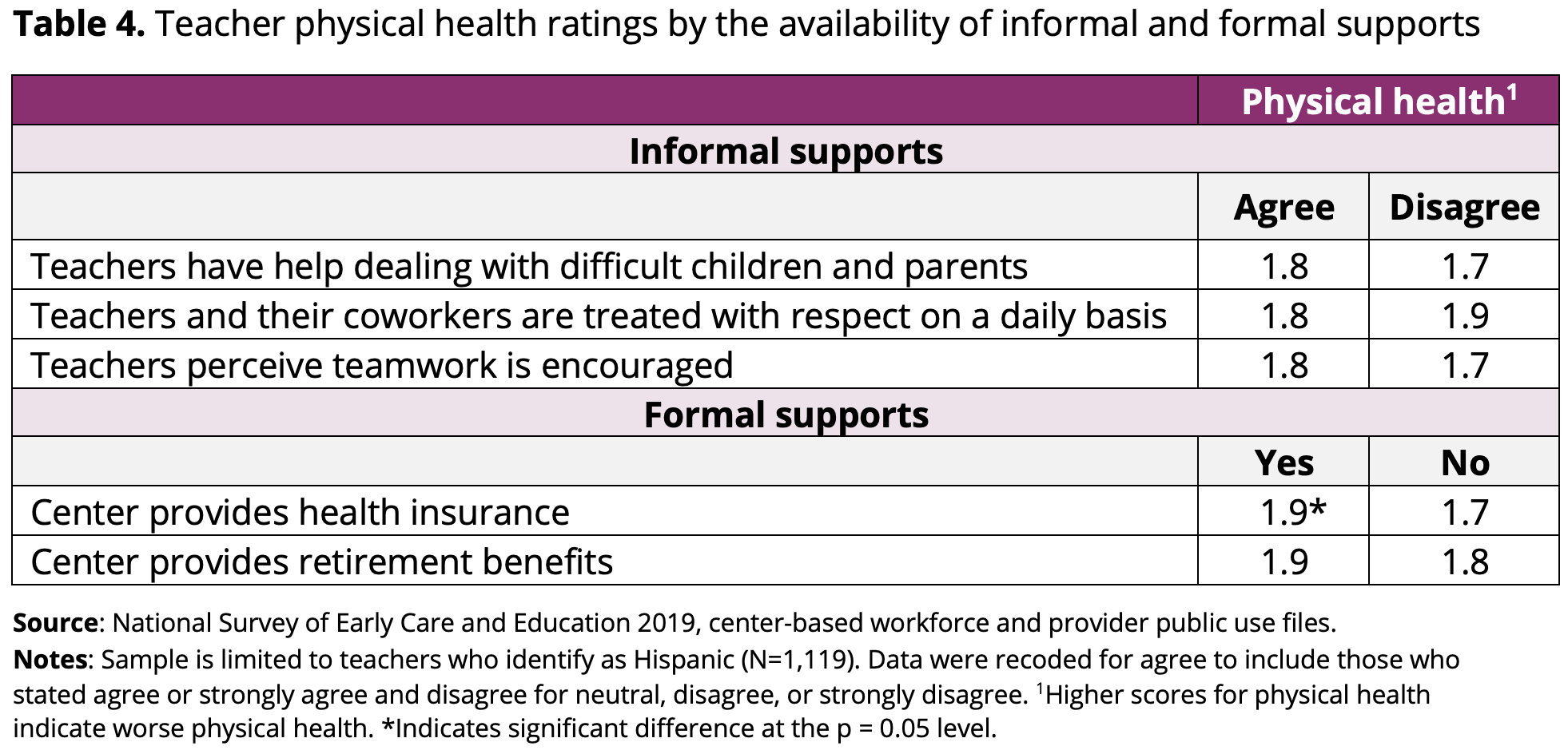

Informal and formal supports are key factors that contribute to Latino ECE workforce well-being. Informal supports can come in different forms, including help working with families whose children are exhibiting difficult behaviors, being treated with respect, and being in an environment where teamwork is encouraged. Formal supports may include teachers’ access to retirement benefits and health insurance. To further examine well-being, we examined whether teacher depressive symptom scores and physical health ratings varied according to the presence of informal and formal supports (Figures 4 and 5, respectively). For informal supports, teachers indicated the extent to which they agreed or disagreed with several statements, including that they have help dealing with children or parents they perceive to be difficult, that they are treated with respect, and that teamwork is encouraged. In terms of formal supports, center directors responded in a yes/no fashion to whether health insurance and retirement benefits for teachers were available or absent from their programs.

Figure 4 indicates that educators who perceived less informal support from their programs had higher levels of depressive symptoms. That is, Hispanic educators who generally agreed that they had help dealing with children or their parents that they perceive to be difficult had lower scores on the CES-D-SF than teachers who did not feel they had this support. Similarly, teachers who agreed that they and their coworkers are treated with respect on a daily basis also had significantly fewer depressive symptoms. Finally, teachers who agreed that teamwork is encouraged at their center also had significantly fewer depressive symptoms than those who did not.

Figure 4: Teacher depressive symptoms are lower with higher ratings of informal supports

Hispanic ECE teachers’ depression symptom scores by their ratings of receipt of informal supports, 2019 Finally, we compared depression symptom scores for educators in programs with and without the formal supports of health insurance and retirement benefits (Figure 5). We found that teachers in programs offering health insurance had higher depressive symptom scores than those in programs without health insurance. There were no differences by the availability of retirement benefits.

Finally, we compared depression symptom scores for educators in programs with and without the formal supports of health insurance and retirement benefits (Figure 5). We found that teachers in programs offering health insurance had higher depressive symptom scores than those in programs without health insurance. There were no differences by the availability of retirement benefits.

Figure 5: Reported depressive symptom scores are higher among teachers within programs offering health insurance coverage

Hispanic ECE teachers’ depressive symptoms scores by whether programs offer health insurance and retirement benefits, 2019

Discussion

This study sheds light on the mental and physical well-being of an understudied group of providers: the Hispanic ECE workforce, most of whom are women (sample is 2% male). Overall, we found that, in 2019, about 8 percent of Hispanic ECE providers had reported depression symptoms at high levels that are consistent with clinical depression. Moreover, about 12 percent reported being in fair or poor physical health, and rates of poor physical health were more common among providers who had more than 10 years of teaching experience. At the same time, over 25 percent reported looking for new or additional work, with 50 percent of those searching indicating that their current job does not provide enough financial support or opportunities for advancement (10%). Taken together, the Hispanic ECE workforce is showing some signs of stress, with well-being and intentions to stay in jeopardy for many.

In this study, we also found that informal supports, such as efforts involving teamwork and collaboration, are essential to thriving in early childhood environments. Given that this study has indicated that educators who perceive informal supports to be present in their program had lower depressive symptoms, programs should use professional development experiences for teachers to create positive and supportive climates. Learning communities may represent a way to help Hispanic providers access more informal supports. For example, hybrid or in-person strategies for bringing together Hispanic providers across centers can help create affinity groups and strengthen networks and sharing of resources or supports. This, in turn, may boost program climate in a way that also improves classroom practices and quality for children.

Head Start is an organization that has highlighted staff wellness, noting that staff who are “happier, healthier, less stressed, and experience less depression are able to engage in higher quality interactions with children.”4 The Office of Head Start has also illustrated several strategies that could promote staff well-being, including fostering a climate of “mutual respect, trust, and teamwork”4—all of which are qualities that this study found supported staff wellness. In addition, Head Start programs were encouraged to support staff by offering breaks, additional resources such as employee assistance programs, and celebrations of staff accomplishments. These supports can all be part of a healthy workplace climate in any ECE environment.

This study raises significant concern regarding the 8 percent of providers reporting clinical depression and the 14 percent who reported fair or poor physical health—a sizeable amount of the overall workforce. Although we found that educators in programs with health insurance had higher rates of depressive symptoms, this finding must be studied more carefully to better capture the nuances of this employer benefit. A study using the NSECE 2019 found that Hispanic and Black adults report higher rates of uninsurance and lower rates of private health insurance than their White and Asian counterparts6; however, how this benefit aligns with depressive symptoms remains less clear. It could be that Hispanic individuals in these settings face other factors that contribute to their depression, or that they fail to access care that is timely and helpful. Alternately, educators who experience depression or other health challenges may seek employment that comes with health insurance. Prior studies have shown that many Latino parents of young children are underserved by the mental health system,7 and educators who have children of their own would also fall within this group. In general, we can conclude that mental health services and access to treatment for Latino individuals remain important priorities.

Finally, we do not have current data on the well-being of the Hispanic ECE workforce, as these data from 2019 shed light on how this population was faring just prior to the COVID-19 pandemic. One snapshot of a subsample of teachers from 2019 through 2021, during the pandemic, shows that as high as one third of Latino center-based teachers were experiencing depressive symptoms—the highest rates of all ethnic groups in the sample.8 While depressive symptoms were more widespread during the pandemic, continued work with the NSECE 2024 will show whether and how those rates have changed for Latino ECE workers. Ultimately, focusing on creating a positive work climate and increasing access to mental health supports may represent important strategies for retaining and enhancing the well-being of the Hispanic ECE workforce, thereby ensuring that young Latine children have access to high-quality and culturally competent teachers in their ECE programs.

Data and Methodology

Sample

Data for this analysis come from the National Survey of Early Care and Education (NSECE) 2019 study, a set of four interrelated, nationally representative surveys of 1) center-based providers, 2) the center-based provider workforce, 3) home-based providers, and 4) households with children under age 13. We use data from the public use center-based workforce and provider surveys to describe the center-based workforce. This ECE workforce sample includes lead teachers, assistants, and aids who work in community-based centers, pre-kindergarten programs, and Head Start programs.

The analytic sample for this brief includes 1,119 center-based teachers who identify as Hispanic and serve children from birth to age 5 (not yet in kindergarten; Table 1). Data weights were included in this analysis so that estimates are representative of 224,817 Latine teachers nationally. We conducted descriptive analysis on the Hispanic workforce on select characteristics, indicators of well-being, informal supports, and formal supports (see Definitions below). Overall, the Hispanic ECE workforce shows moderate levels of education and is relatively new to teaching. As indicated in Table 1, 57 percent are teachers (including instructors and lead teachers), and 44 percent are assistant teachers or aides. Forty percent of this sample has a bachelor’s degree or higher. Many Latina teachers have been in their program for 1 year or less (39%) or 2-5 years (32%), although there is a share of very experienced teachers with 6-10 years (16%) or more than 10 years of experience (13%). The majority of teachers are younger than 45 years old. Most teachers reported serving children ages 3-5 (69%), although a large share also reported serving children from birth to age 2 (59%). Mean comparisons of teacher CES-D-SF, the primary measure of depressive symptoms, and physical health rating scores were conducted by teacher characteristics, informal supports, and formal supports. Significant differences at the p=0.05 level are noted. All analyses were conducted in STATA and weighted to be nationally representative of Hispanic teachers in center-based settings.

Definitions

Hispanic ethnicity: Indicates whether the teacher/caregiver reported that they identify as Hispanic.

Physical health: Indicates teachers’ response to the question, “Overall, would you say your health is excellent, very good, fair, or poor?” Higher ratings indicated lower self-report of physical health.

Depressive symptoms (CES-D-SF): Teachers responded to a set of 7 items from the Center for Epidemiological Studies Depression (CES-D) that asked about their overall depressive and mental health symptoms. Response options for each item ranged from 0-3 (0 = “Rarely or none of the time [less than 1 day]”; 3 = “All of the time [5-7 days”]). Teachers’ response to the 7 items were added to provide a CES-D score ranging from 0 (not at all depressed) to 21 (symptoms of severe depression). A cutoff of 8 or higher is recommended to identify individuals with suspected major depressive disorder.

Frequency of depressive symptoms: Reflects teachers’ response to an item from the CES-D asking how often they have felt depressed during the past week. Response options were coded 0-3 and included “Rarely or none of the time (less than 1 day),” “Some or little of the time (1-2 days),” “Occasionally or moderate amount of time (3-4 days),” or “All of the time (5-7 days).” Higher scores indicated a higher frequency of depressive symptoms.

Reasons for working with young children: Reflects teachers’ response to the question, “Which of the following best describes the main reason that you work with young children?” Teachers could choose between eight response options that were provided by the NSECE researchers.

Reasons for looking for work: Teachers who answered “Yes” to the question, “In the past 3 months, have you done anything to look for an additional job” (25% of analytic sample) then provided a response to the question, “What is the main reason you have looked for work?” Response options were determined by the NSECE researchers. For teachers who indicated “other” reasons, responses were coded by NSECE researchers to add indicators for those wanting to find a job with benefits/insurance, more work hours, or work in a new area because they had moved/relocated.

Availability of help: Teachers reported how much they agree or disagree with the following statements about working in the program: “I have help dealing with difficult children or parents. Would you say you strongly agree, agree, neither agree or disagree, disagree, or strongly disagree with this statement?”

Teacher perception of respect: Teachers reported how much they agree or disagree with the following statements about working in the program: “My co-workers and I are treated with respect on a day-to-day basis. Would you say you strongly agree, agree, neither agree or disagree, disagree, or strongly disagree with this statement?”

Extent that teamwork is valued: Teachers reported how much they agree or disagree with the following statements about working in the program: “Teamwork is encouraged. Would you say you strongly agree, agree, neither agree or disagree, disagree, or strongly disagree with this statement?”

Center provides health insurance: Captures whether the center-based provider offers health insurance to their staff by asking, “Do you provide any of the following benefits to your teachers, assistant teachers, or aids? Health Insurance.”

Center provides retirement benefits: Captures whether the center-based provider offers a retirement program to their staff by asking, “Do you provide any of the following benefits to your teachers, assistant teachers, or aids? Retirement program such as retirement annuity, 401(k) or 403(b) plan.”

Footnotes

Footnotes

aWe use “Hispanic,” “Latino,” “Latinx,” and “Latine” interchangeably throughout the brief. The terms are used to reflect the U.S. Census definition to include individuals having origins in Mexico, Puerto Rico, and Cuba, as well as other “Hispanic, Latino or Spanish” origins.

bWe may use “Hispanic,” “Latino,” “Latinx,” and “Latine” interchangeably throughout the brief. The terms are used to reflect the U.S. Census definition to include individuals having origins in Mexico, Puerto Rico, and Cuba, as well as other “Hispanic, Latino or Spanish” origins. However, even though the vast majority of ECE teachers are female—in this sample, less than 2 percent of teachers identified as male—we most often use the gender-neutral term “Hispanic.”

c Author analysis, 2024.

Suggested Citation

Mendez, J., Stephens, C., Jacome, A., & Crosby, D. A. (2024). Informal and formal supports may affect Hispanic early educators’ physical and mental well-being. National Research Center on Hispanic Children & Families. https://www.hispanicresearchcenter.org/research-resources/informal-and-formal-supports-may-affect-hispanic-early-educators-physical-and-mental-well-being DOI: https://doi.org/10.59377/100s2482j

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to thank the Steering Committee of the National Research Center on Hispanic Children & Families—along with Sara Amadon, Kristen Harper, Laura Ramirez, and Ana Maria Pavić—for their helpful comments, edits, and research assistance at multiple stages of this project. The Center’s Steering Committee is made up of the Center investigators—Drs. Natasha Cabrera (University of Maryland, Co-PI), Danielle Crosby (University of North Carolina at Greensboro, Co-PI), Lisa Gennetian (Duke University; Co-PI), Lina Guzman (Child Trends, Director and PI), Julie Mendez (University of North Carolina at Greensboro, Co-PI), and María Ramos-Olazagasti (Child Trends, Deputy Director and Co-PI)—and federal project officers Drs. Ann Rivera, Jenessa Malin, and Kimberly Clum (Office of Planning, Research and Evaluation), and Dr. Shirley Huang (Society for Research in Child Development Policy Fellow, Office of Planning, Research and Evaluation). Finally, we express our appreciation for the Texas state and local agency partners who helped facilitate the study and the subsidy staff and administrators who were generous with their time and responded to the survey.

Editor: Brent Franklin

Designers: Catherine Nichols & Joseph Boven

About the Authors

Julia Mendez, PhD, is a co-principal investigator of the National Research Center on Hispanic Children & Families, co-leading the research area on early care and education. She is a professor in the Department of Psychology at the University of North Carolina at Greensboro. Her research focuses on risk and resilience among ethnically diverse children and families, with an emphasis on parent child interactions and family engagement in early care and education programs.

Christina Stephens, PhD, was previously a pre-doctoral fellow with the National Research Center on Hispanic Children & Families, in the research area on early care and education. Christina’s research focuses on understanding the factors and policies that promote child care access and quality, particularly among low-income families with young children and dual language learners. She is now a postdoctoral researcher at the University of Virginia with the Education Science Training Program on English Learners (EL-VEST). A portion of her effort on this project was supported by the Institute of Education Sciences, U.S. Department of Education, through Grant R305B210008 to the University of Virginia. The opinions expressed are those of the authors and do not represent views of the Institute or the U.S. Department of Education.

Anyela Jacome, is a graduate student in a Clinical Psychology program at the University of North Carolina at Greensboro. She received her Master’s degree from the University of Maryland, College Park in Clinical Psychological Science. Her research interests focus on the well-being of children and families and understanding risk and protective factors in the context of culture. She also has interests in family engagement in early care and education programs.

Danielle A. Crosby, PhD, is a co-principal investigator of the National Research Center on Hispanic Children & Families, co-leading the research area on early care and education. She is an associate professor in the Department of Human Development and Family Studies at the University of North Carolina at Greensboro. Her research focuses on understanding how policies and systems shape early education access and quality for young children in low-income families.

About the Center

The National Research Center on Hispanic Children & Families (Center) is a hub of research to help programs and policy better serve low-income Hispanics across three priority areas: poverty reduction and economic self-sufficiency, healthy marriage and responsible fatherhood, and early care and education. The Center is led by Child Trends, in partnership with Duke University, University of North Carolina at Greensboro, and University of Maryland, College Park. This publication is supported by the Administration for Children and Families (ACF) of the United States (U.S.) Department of Health and Human Services (HHS) as part of two financial assistance awards (Award # 90PH0028, from 2018-2023, and Award # 90PH0032 from 2023-2028) totaling $13.5 million across the two awards with 99 percentage funded by ACF/HHS and 1 percentage funded by non-government sources. The contents are those of the authors and do not necessarily represent the official views of, nor an endorsement, by ACF/HHS, or the U.S. Government. For more information, please visit the ACF website, Administrative and National Policy Requirements.

© Copyright 2024 National Research Center on Hispanic Children & Families — All Rights Reserved

References

1Smith, S., & Lawrence, S. M. (2019). Early care and education teacher well-being: Associations with children’s experience, outcomes, and workplace conditions: A research-to-policy brief. Child Care & Early Education Research Connections. https://doi.org/10.7916/d8-ngw9-n011

2Hill, Z., Gennetian, L.A., & Mendez, J. (2019). A descriptive profile of state Child Care and Development Fund policies in states with high populations of low-income Hispanic children, Early Childhood Research Quarterly, 47, 111-123. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ecresq.2018.10.003

3Madill, R., Halle, T., Gebhart, T., & Shuey, E. (2018). Supporting the psychological well-being of the early care and education workforce: Findings from the National Survey of Early Care and Education. OPRE Report #2018-49. Washington, DC: Office of Planning, Research and Evaluation, Administration for Children and Families, U.S. Department of Health and Human Services. https://www.acf.hhs.gov/opre/report/supporting-psychological-well-being-early-care-and-education-workforce-findings

4Early Childhood Learning & Knowledge Center. (2021). Supporting the Wellness of All Staff in the Head Start Workforce ACF-IM-HS-21-05. U.S. Department of Health & Human Services, Office of Head Start, Early Childhood Learning & Knowledge Center. https://eclkc.ohs.acf.hhs.gov/policy/im/acf-im-hs-21-05

5Geldenhuys, M., Łaba, K., & Venter, C. M. (2014). Meaningful work, work engagement and organisational commitment. SA Journal of Industrial Psychology, 40(1). https://doi.org/10.4102/sajip.v40i1.1098

6Amadon, S., Maxfield, E., Simons Gerson, C., & Keaton, H. (2023). Health Insurance Coverage of the Center-Based Child Care and Early Education Workforce: Findings from the 2019 National Survey of Early Care and Education. OPRE Report #2023-293. Office of Planning, Research, and Evaluation, Administration for Children and Families, U.S. Department of Health and Human Services. www.acf.hhs.gov/opre/report/health-insurance-coverage-center-based-child-care-and-early-education-workforce

7Ramos-Olazagasti, M., & Conway, A. (2022). The Prevalence of Mental Health Disorders Among Latino Parents. National Research Center on Hispanic Children and Families. https://www.hispanicresearchcenter.org/research-resources/the-prevalence-of-mental-health-disorders-among-latino-parents/

8Park, J. & A. Rupa Datta (2023). NSECE Snapshot: Mental Health and Well-being of Center-based Child Care Workers from 2019 during the COVID-19 Pandemic: Key Findings by Race and Ethnicity, OPRE Report #2023-252. Office of Planning, Research, and Evaluation, Administration for Children and Families, U.S. Department of Health and Human Services. https://www.acf.hhs.gov/opre/report/nsece-snapshot-mental-health-and-well-being-center-based-child-care-workers-2019-during

Copyright 2025 by the National Research Center on Hispanic Children & Families.

This website is supported by Grant Number 90PH0032 from the Office of Planning, Research & Evaluation within the Administration for Children and Families, a division of the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services totaling $7.84 million with 99 percentage funded by ACF/HHS and 1 percentage funded by non-government sources. Neither the Administration for Children and Families nor any of its components operate, control, are responsible for, or necessarily endorse this website (including, without limitation, its content, technical infrastructure, and policies, and any services or tools provided). The opinions, findings, conclusions, and recommendations expressed are those of the author(s) and do not necessarily reflect the views of the Administration for Children and Families and the Office of Planning, Research & Evaluation.