Most Hispanic Children in Households With Low Incomes Received Medical Care in the Past Year

Nov 25, 2025

Data Point

Most Hispanic Children in Households With Low Incomes Received Medical Care in the Past Year

Author

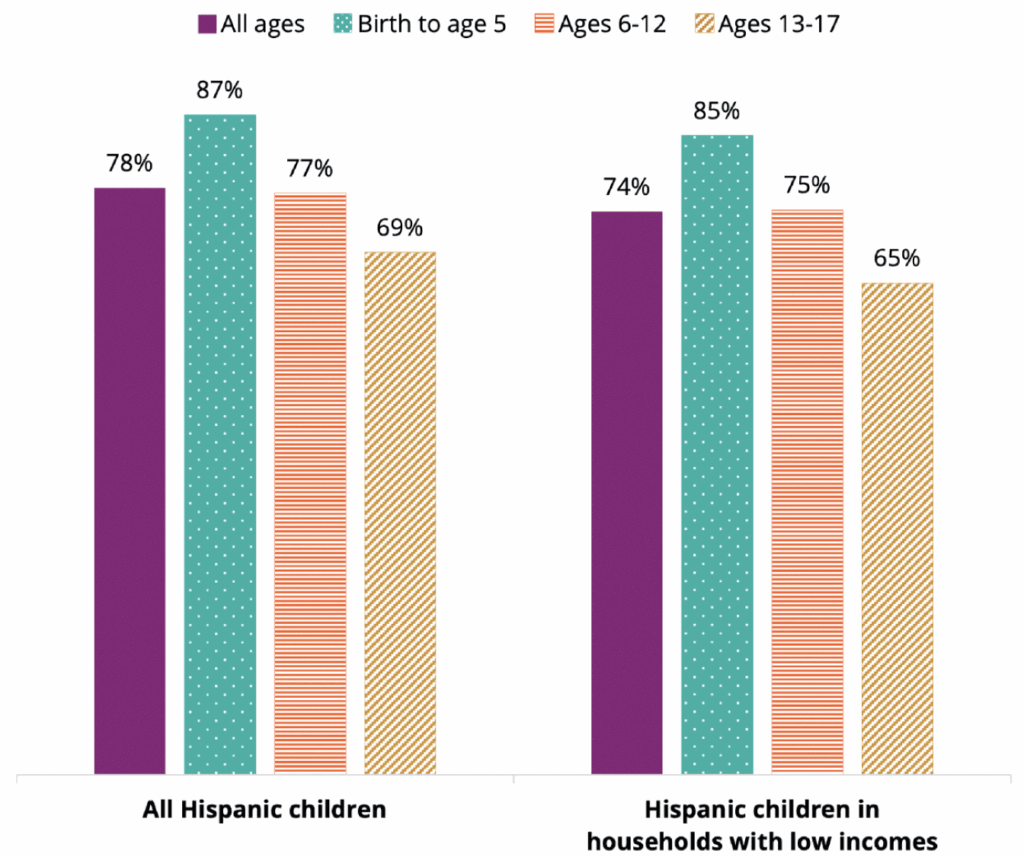

About three quarters of Hispanic children living in families with low incomes received medical care in the past year, according to our new analysis of 2022 and 2023 data from the National Survey of Children’s Health. For this analysis, we examined in-person and/or telehealth medical care use among children in households with incomes less than 200 percent of the federal poverty level (FPL). As shown in Figure 1, receipt of medical care in the past year varied by child age, with younger children (birth to age 5) more likely to have received medical care (85%) than older children (ages 6-12, 75%) and teens (ages 13-18, 65%). Although most Hispanic children and youth across age groups accessed medical care, a notable proportion—one in four—had not seen a doctor, nurse, or urgent/emergency care in at least one year (22% of Hispanic children across all income levels and 26% for Hispanic children in households with low incomes).

Figure 1. Most Hispanic children received medical care in the past year, including in households with low incomes (2022-2023)

Percentage of Hispanic children who received any medical care in the past year (2022-2023), overall and by age and household income*

Notes: Sample includes Hispanic children under age 18 who are not missing data on medical care. All pairwise differences by age group are statistically significant in analyses for all Hispanic children and for Hispanic children in households with low incomes (p < 0.01). *Because the analyses for all Hispanic children and Hispanic children in households with low incomes are not mutually exclusive, we did not conduct significance testing by income level.

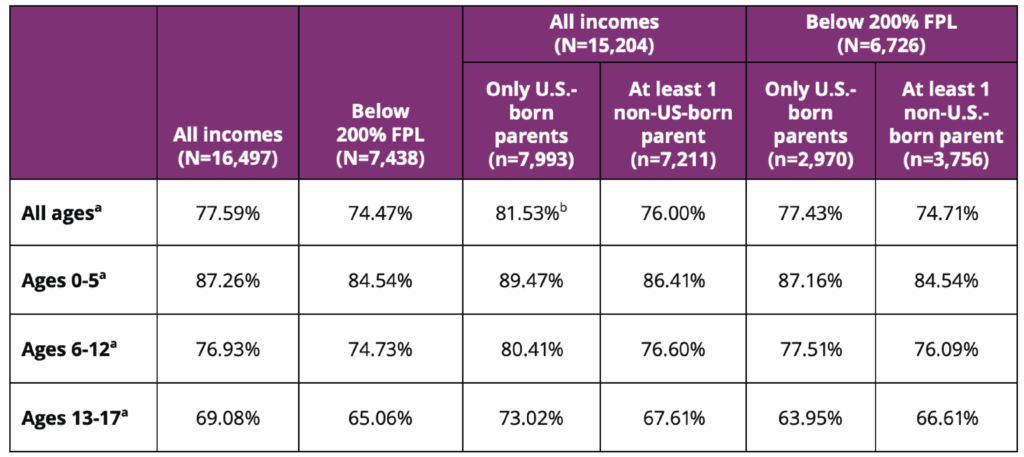

In addition, Hispanic children whose parents were both born in the United States had significantly higher rates of receiving medical care in the last year, relative to Hispanic children with at least one parent born outside of the United States (Table A). These differences were only observed when examining children across all income levels. There were no significant differences by parental birthplace within specific age groups or for children living in families with low incomes.

Bright Futures/American Academy of Pediatrics publishes a recommended schedule of preventative health visits from birth to age 21. Recommended visits are more frequent in a child’s first three years to track important milestones during rapid periods of development; provide immunizations; and conduct early screening, detection, and referral to additional care as needed. After a child’s third birthday, recommended preventative visits move to an annual basis. In addition to preventative care, children and youth may require acute and emergency care for more immediate medical needs, such as injury or illness.

There are numerous benefits to children receiving routine and timely medical care, including improved physical, emotional, and mental health; healthy growth and development; and better academic performance. Among children with chronic health conditions, routine medical care is key to managing the condition and preventing its progression to a more serious level.

However, several factors can pose barriers to Hispanic children’s regular access to medical care in the United States, including lack of health insurance coverage. Even with coverage, families may struggle to pay for out-of-pocket costs, which can lead them to avoid accessing medical care and attending regular appointments. Health care costs are rising rapidly, a trend that is disproportionately affecting families with low incomes. From 2020-2024, health care premiums for U.S. families rose by 20 percent, with many parents reporting an inability to afford health care coverage at all. Rising costs and loss of coverage for families with low incomes place children at risk for negative consequences to their health, development, and well-being.

Many programs and systems that work with families, such as Head Start and school-based health programs, may facilitate connections to pediatric medical care through community referrals, telehealth delivery, or on-site services. For example, Head Start Program Performance Standards require center- and home-based staff to partner with families to ensure connections to medical care within 30 days of program enrollment, and to obtain follow-up documentation of up-to-date medical care in coordination with health providers. These systems may also work to address families’ barriers to accessing medical care for children, including insurance enrollment, cost of care, multilingual provider access, and fear of medical systems.

Methods

For this analysis, we used data from the 2022 and 2023 National Survey of Children’s Health (NSCH), obtained via the Child and Adolescent Health Measurement Initiative (CAMHI) Data Resource Center for Child and Adolescent Health (DRC). The NSCH, conducted by the Census Bureau, is a household survey that provides nationally representative data on the health of children from birth to age 17 in the United States. We define Hispanic children as those with reported Hispanic, Latino, or Spanish origin, regardless of race. Our analytic sample includes Hispanic children for whom data on medical care in the past year were not missing (43 children, or 0.3%, were missing data on medical care), resulting in a full unweighted sample of 16,497 Hispanic children, including approximately 7,438 Hispanic children in families with low incomes. We used survey-adjusted Wald tests to assess pairwise differences for age groups and parental birthplace, applying a Benjamini–Hochberg correction to adjust for multiple comparisons. Our measure of medical care is based on the following item: “During the past 12 months, did this child see a doctor, nurse, or other health care professional for sick-child care, well-child check-ups, physical exams, hospitalizations or any other kind of medical care (including health care visits done by video or phone)?”, which we coded as 1=yes and 0=no. We created the category of families with low incomes (<200% of the federal poverty threshold) using the imputed family poverty variable, which is calculated as the ratio of total family income to the family poverty threshold.1 For Hispanic children who live with at least one parent (n=15,204),2 we also show estimates according to whether children’s coresidential parents were born in the United States or in another country, using two categories: 1) both parents in the household were born in the United States; and 2) at least one parent in the household was born outside the United States. For children with only one parent in the household, parental nativity was assigned based on the nativity of that parent alone.

Table A. Percentage of Hispanic children who received any medical care in the past year, by age, family income, and parental birthplace

Source: Authors’ analysis of the 2022 and 2023 National Survey of Children’s Health.

Source: Authors’ analysis of the 2022 and 2023 National Survey of Children’s Health.Notes: Sample includes Hispanic children under age 18 who are not missing data on medical care. Analysis by parental country of birth excludes children not living with at least one parent.

a All pairwise differences by age group within each column are statistically significant (p < 0.01).

b The difference between children with all U.S.-born parents and at least one immigrant parent was statistically significant (p<0.001) for all Hispanic children.

Suggested Citation

Vivrette, R., Maxfield, E., & Ramos-Olazagasti, M. A. (2025). Most Hispanic children in households with low incomes received medical care in the past year. National Research Center on Hispanic Children & Families. DOI: https://doi.org/10.59377/472p1010f

Footnotes

1 Income data are multiply imputed in the NSCH. Per the approach used in the CAMHI DRC, we report the unweighted sample size from the first implicate only. Note that analyses were completed with the full multiply imputed data. See the NSCH technical documentation for additional information.

2 Including biological parents, adoptive parents, and stepparents.

Copyright 2025 by the National Research Center on Hispanic Children & Families.

This website is supported by Grant Number 90PH0032 from the Office of Planning, Research & Evaluation within the Administration for Children and Families, a division of the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services totaling $7.84 million with 99 percentage funded by ACF/HHS and 1 percentage funded by non-government sources. Neither the Administration for Children and Families nor any of its components operate, control, are responsible for, or necessarily endorse this website (including, without limitation, its content, technical infrastructure, and policies, and any services or tools provided). The opinions, findings, conclusions, and recommendations expressed are those of the author(s) and do not necessarily reflect the views of the Administration for Children and Families and the Office of Planning, Research & Evaluation.