Practitioners in North Carolina’s TANF and Related Income Assistance Programs Offer Perspectives on Latino Families’ Experiences

Dec 15, 2022

Research Publication

Practitioners in North Carolina’s TANF and Related Income Assistance Programs Offer Perspectives on Latino Families’ Experiences

Author

Introduction

Income support to families who live in poverty is positively associated with multiple aspects of children’s well-being, including their educational attainment, cognitive development, and social and behavioral skills.1 However, not all income-eligible families have equal access to government support and, even when eligible families do have access, some do not take up benefits.2 The reasons for lower uptake among eligible families are complex. First, there may not be enough funding for government programs to cover all eligible families. Second, assuming funding is available to support all eligible families, other factors—such as misinformation about eligibility and challenges to meeting eligibility criteria, rules, or securing the needed documentation—may affect uptake.2,3,4,5,6,7

About this brief

This brief is part of a series to examine state-level policies that relate to social service and safety net programs and the ways in which state and federal policy implementation at the local level may affect the reach of program benefits among Latino families. The series draws on publicly available data related to state-level policy and guidelines regarding eligibility and requirements for income assistance and support programs (TANF, the Earned Income Tax Credit, and child care subsidies), the user interface of states’ online application systems, and newly collected data from state and local administrators and practitioners from states in which Latino children make up a large proportion of all children. To date, related research examining state-level policy and practice from the perspective of Latino families is available for the Child Care and Development Fund (CCDF) child care subsidy program (see here and here) and Temporary Assistance to Needy Families (TANF) income assistance programs (see here and here), across and within multiple state contexts.

In prior work, we have discussed how Hispanic families’ experiences with safety net and income assistance programs such as Temporary Assistance for Needy Families (TANF) may be uniquely affected by these and related characteristics, including the English literacy and language proficiency demands of program applications and other program-related interactions; the program eligibility implications of complex household structures, caregiver relationships, and citizenship statuses of household members; and fear and distrust resulting from anti-immigrant sentiment and restrictions.8,9 For this analysis, to better understand how these and other related considerations intersect with program implementation, we designed a unique survey that collected data from administrators and frontline staff in 11 states with large populations of Latinoa families about their perspectives and experiences administering TANF and related income assistance programs.(This brief will generally use the phrase “income assistance programs” to refer to this combination of programs.) In their responses, practitioners reported on various organizational practices related to families’ access and engagement, perceptions of language barriers, and organizational culture. The survey also touched on aspects of offices’ physical safety and security and welcoming environments.b

This brief examines Latino families’ experiences with North Carolina’s TANF (also known as Work First) and related income assistance programs, based on practitioner responses to a survey that included a questionnaire and a series of open-ended questions. In this brief, we first summarize key findings from our analysis of practitioners’ survey responses. Second, to provide context, we discuss North Carolina’s Hispanic population and how the state’s income assistance programs are administered. Third, we review our findings, in more detail, on income assistance program practitioners’ perspectives on Latino families’ experiences with these programs. Fourth, we discuss the implications of our findings for how income assistance programs are administered in North Carolina and in other states with large and growing Latino populations. Finally, we describe the survey in more detail and review our analysis methods.

Defining the Roles of TANF and Related Income Assistance Staff

Specific practitioner job titles and functions can vary across North Carolina counties and benefits systems. Among employees in the Department of Health and Human Services who focus on North Carolina’s income assistance programs, as described in this brief, administrators are those who indicated a job title at the manager, supervisory, or director level (e.g., program manager, economic services program manager, Work First supervisor). Frontline workers are those who indicated job titles that included caseworker, eligibility worker, and, in some cases, specialist. We use the inclusive term “practitioners” to refer to employees at these levels.

Key Findings

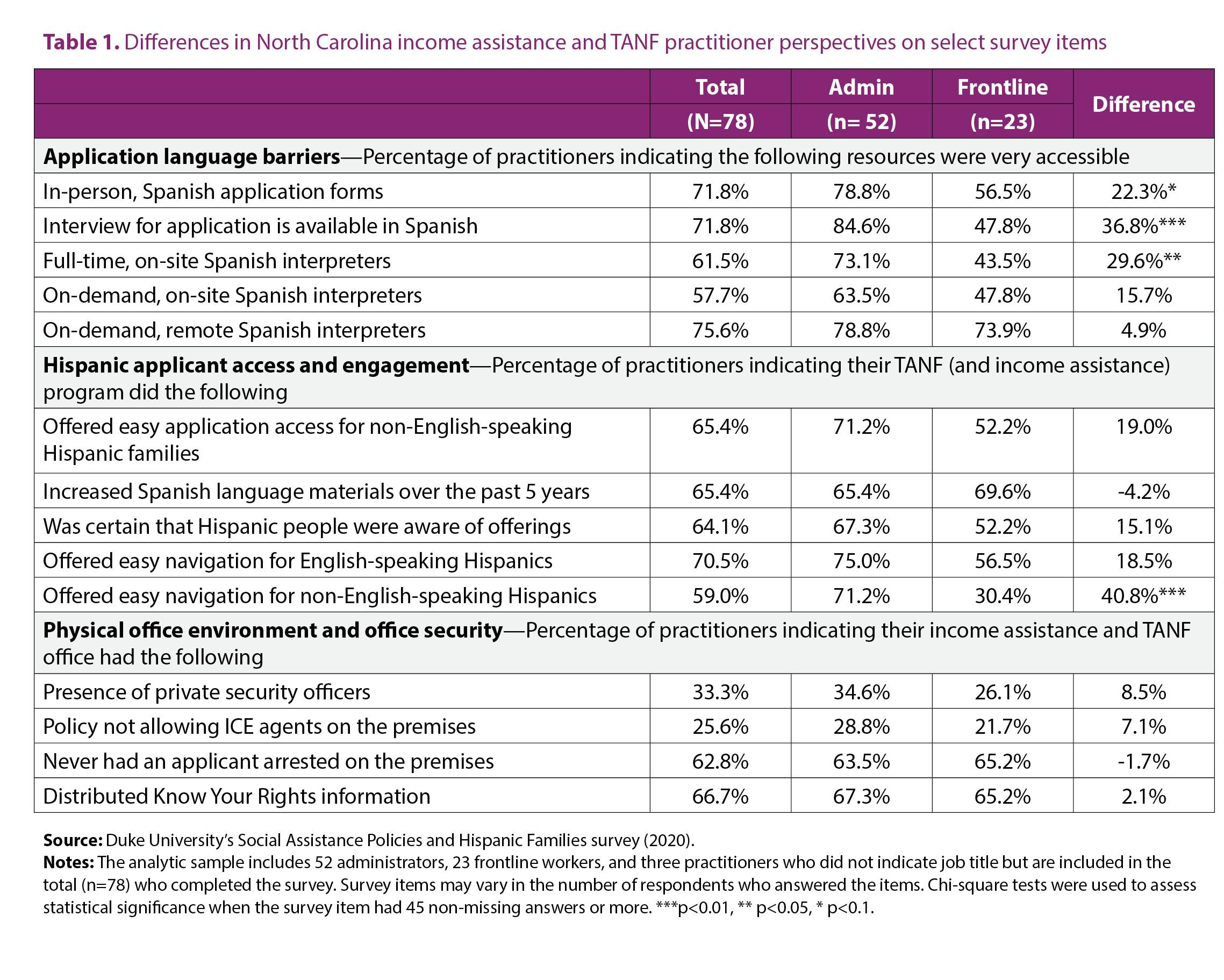

County administrators and frontline workers in North Carolina’s income assistance and TANF program offices have similar perceptions with respect to documentation requirements, access, and office safety and security affect program uptake among Latino families. However, in some cases, county administrators and frontline workers had differing views on Latino families’ experiences related to documentation requirements, access, and office safety and security. One reason for such a divide might be that frontline workers’ impressions are informed by more direct and frequent interaction with clients.

Ease of program navigation

- Administrators were more likely than frontline staff to feel that applying to and navigating North Carolina’s income assistance and TANF programs were easy for Hispanics. While 71 percent of practitioners felt that these programs were easy for English-speaking Hispanics to navigate, only 59 percent felt the same for non-English-speaking Hispanics (71% of administrators and 30% of frontline workers).

Availability of program and application supports

- Nearly all practitioners—both administrators (79%) and frontline workers (74%)—believed that non-English-speaking Hispanic clients have adequate remote access to on-demand interpreters.

- However, administrators and frontline workers did not agree on whether it is easy for Latino families to access on-demand, on-site interpreters: 73 percent of income assistance and TANF program administrators and 44 percent of frontline workers said that full-time, on-site interpreters are very accessible.

- There were similar disagreements on the accessibility of in-person application forms in Spanish (79% of administrators, 57% percent of frontline workers) and application interviews in Spanish (85% of administrators, 48% of frontline staff).

- Practitioners strongly agreed that there has been an increase in Spanish-language application materials over the last five years.

- Administrators were, overall, more likely than frontline staff to feel that Spanish-language application materials and interpreters were available and accessible to Hispanic clients. This may point at a potential language barrier that could impact program participation and may not be evident to administrators, who are not likely to interact often with clients.

- Most practitioners surveyed felt that Hispanic people in their communities were aware of the program, and of the services and resources offered at the income assistance and TANF program office.

Co-location of TANF and other income assistance programs with other types of benefits and services

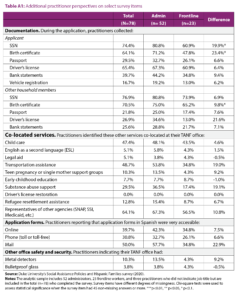

- About half of all practitioners indicated that TANF and other income assistance program applicants could access child care benefits at the program office, and two thirds said that applicants could access representatives from income assistance programs other than the one to which they were currently applying. Administrators were substantially more likely than frontline workers to report that income assistance and TANF program applicants could access transportation assistance (54% and 37%, respectively) and substance abuse support (37% and 17%).

Collection of documents

- More than four in five administrators reported collecting applicants’ Social Security Numbers (SSNs), but only three in five frontline workers reported doing the same. Similarly, about 71 percent of administrators reported collecting applicants’ birth certificates, compared to only 48 percent of frontline workers.

- These differences are important: On one hand, collecting such documents may increase burden for Hispanic applicants; however, it may also be that frontline workers use discretion across a variety of documents to decrease applicant burden and facilitate completion of the application.

Physical office environment and office security

- Approximately two thirds of practitioners reported that a client had never been arrested in a TANF or other income assistance program office (63%)—a potential source of fear for applicants—and that clients received legal information about immigration concerns (67%). Relatively few reported the presence of private security, metal detectors, or bulletproof glass.

NORTH CAROLINA STATE CONTEXT

Hispanic population and trends in North Carolina

From 2010 to 2020, North Carolina’s Hispanic population grew by approximately 40 percent.10 By 2020, Hispanics represented roughly 10 percent of the state’s population. Two thirds of the Hispanic population in North Carolina is U.S.-born, with Mexico, Honduras, El Salvador, and Guatemala representing the main countries of heritage. The more than 1 million Hispanic residents in North Carolina, as of 2020, make it the state with the third largest Hispanic population in the U.S. South, just behind Florida and Georgia.

Figure 1: Hispanic Population in North Carolina, by County

Source: 2019 American Community Survey 1-Year Data.

As shown in Figure 1, the Hispanic population is scattered across various pockets of North Carolina. More than one in four Hispanic residents can be found in Wake County and Mecklenburg County, while other areas such as Sampson, Duplin, and Onslow counties in the Coastal Plains show the highest growth in the Hispanic population. North Carolina Hispanics have a higher labor force participation rate than non-Hispanics.11,12,13 However, the poverty rate of Hispanics overall (22.1%)—and of Hispanic children (29.8%)—is higher than the state population average of 13.6 percent and 19.5 percent, respectively.14,15

TANF basic assistance in North Carolina

The Work First (TANF) program in North Carolina aims to support income-eligible caregivers by providing them with time-limited cash assistance while they search for or engage in work or work-related activities.16 In North Carolina, the TANF basic assistance program is developed and administered by each of the state’s 100 county governments and supervised by the state Department of Health and Human Services (DHHS). In addition, seven counties have waivers that give them authority to establish eligibility criteria and benefit levels that can differ from state guidelines. North Carolina began rolling out, at the county level, an electronic screening service called ePASS in 2010 (short for “Electronic Pre-Assessment Screening Service”). ePASS was available for families to assess their eligibility for available public benefits and services.17

Local—county and city level—practitioners play a key role in TANF basic assistance program implementation.18,19 The alignment of policy and practitioner priorities with policy objectives is critically important in implementation. On the one hand, client-state or client-county interactions are governed by guidelines and constraints set forth by state-level administrators and policymakers. On the other hand, frontline practitioners can exert discretionary authority in the way they engage directly with individuals and families and implement policy and guidelines.20, 21, 22, 23 In some environments, this discretion may benefit families if frontline officials are able to tailor approaches to meet families’ and communities’ needs and circumstances. In other environments, though, practitioner discretion can lead to misaligned priorities and goals between policy and practice.24

Findings

In this section, we present our findings on organizational practices (such as language barriers and application forms and documentation), as well as organizational culture (program offerings, office services, and office safety and security). Within this analysis, we compare the perspectives shared by county administrators and frontline staff.

Organizational practices and processes

Ease of program navigation: Approximately 71 percent of practitioners reported that income assistance and TANF programs in North Carolina were easy for English-speaking Hispanic applicants to navigate.c However, only 59 percent of practitioners reported the same for non-English-speaking Hispanic applicants. When stratified by position, about 71 percent of administrators reported that the program offered easy navigation for non-English-speaking Hispanics, while only 30 percent of frontline workers agreed. This may point to a potential language barrier that could impact program participation but that may not be evident to administrators, who do not interact often with clients.

for English-speaking Hispanic applicants to navigate.c However, only 59 percent of practitioners reported the same for non-English-speaking Hispanic applicants. When stratified by position, about 71 percent of administrators reported that the program offered easy navigation for non-English-speaking Hispanics, while only 30 percent of frontline workers agreed. This may point to a potential language barrier that could impact program participation but that may not be evident to administrators, who do not interact often with clients.

Availability of program and application supports for non-English speakers: Practitioners also reported differing views regarding the application process and availability of some resources for non-English speakers. Seventy-nine percent of administrators reported that in-person application forms in Spanish were very accessible, compared with 57 percent of frontline workers. Relatedly, when asked about Spanish interpreters for non-English-speaking Hispanic applicants, 73 percent of administrators said that full-time, on-site interpreters were very accessible 44 percent of frontline workers agreed. Similarly, application interviews in Spanish were seen as very accessible by 85 percent of administrator practitioners but by 48 percent of frontline staff. In contrast, approximately three in four administrators (79%) and frontline staff (74%) alike felt that Hispanic applicants had easy access to on-demand, remote interpreters.

In North Carolina, clients can find, fill out, and apply online for SNAP and Medicaid benefits using the ePASS platform. In contrast, the Work First (TANF) application can be found and filled out online but would-be applicants cannot submit and apply for TANF benefits online. About 40 percent of practitioners indicated that the Spanish language version of the application was very accessible through the website. Furthermore, while 65 percent of practitioners noted increased availability of Spanish application materials over the five years prior to the survey, only 52 percent of frontline workers felt that Spanish applications were easy to access, compared to 71 percent of administrators.

Collection of documents for applicants and household members: Over two thirds of all surveyed practitioners indicated that they collect household members’ Social Security Numbers (SSNs) and birth certificates, and about one quarter collect passports, driver’s licenses, and bank statements as well (Table A1). Reports of which documents are requested during applications differed by the job position surveyed: More than four in five administrators said they collect applicants’ SSNs, compared to just three in five frontline workers. Similarly, 71 percent of administrators reported collecting an applicant’s birth certificate, while only 48 percent of frontline workers request that document. Most administrators also reported that the application process collects SSNs (reported by nearly 80%) and birth certificates (nearly 75%) of other household members. Approximately one third reported that other household members’ drivers licenses or bank statements may also be collected. Reports from frontline workers did not substantively differ from administrators with respect to documents collected about other household members.

Co-location of TANF with other income assistance and related services: Co-locating services may also increase access to other public benefits for those applicants who qualify (Table A1). In North Carolina, approximately half of responding practitioners indicated that child care benefits could be accessed through the TANF office on-site, and just over two thirds mentioned that representatives from other agencies (i.e., SNAP, SSI, Medicaid, etc.) were are also available on-site. More administrators reported on-site transportation assistance (54%) and substance abuse support (37%) than frontline workers (only 35% of frontline workers referenced transportation assistance and 17% referenced substance abuse support).

Physical office environment and security: Physical elements of office safety and security can also affect how Hispanic (or any) clients experience services. These elements may include the design of the physical office space, staff behavior and sensitivity, and the co-location of other services.25 For example, the physical office space in which individuals apply for social benefits may implicitly or explicitly be construed as welcoming or threatening. As such, the presence of office security and safety elements may matter.

Witnessing an arrest by a security or police officer, for any cause or violation, may invoke either fear or feelings of safety. Approximately 63 percent of practitioners reported that a client had never been arrested in a TANF office (Table 1). In addition, roughly 35 percent of administrators and 26 percent of frontline practitioners indicated that private security officers were on their premises, while only 10 percent of practitioners mentioned the presence of metal detectors in their office space and almost none mentioned bulletproof glass (Table A1).

Two thirds of surveyed practitioners reported that clients received legal information about their immigration-related concerns, known as “Know Your Rights” information.26 Among the practitioners who responded to the item, approximately one quarter reported that their program office has an explicit policy that does not allow Immigration and Customs Enforcement (ICE) agents on the premises. The pattern of valid responses on these close-ended items is also noteworthy. Approximately 75 percent of respondents skipped this survey item even though they had the option of selecting “I do not know.” However, there is no direct evidence to suggest that this skip pattern can be attributed to typical survey response fatigue.

These practitioner perspectives are notable since one of the main reported barriers to access from the open-ended survey items was families’ fear of government action and concerns related to the immigration status of either the applicant or someone else in their household. A welcoming (or non-threatening) office environment can have many types of spillover effects, including more favorable word-of-mouth impressions offered in communities. In fact, in response to open-ended survey items (see more detail in the next section), practitioners noted that word of mouth is the main way in which program knowledge spreads though the Hispanic community (a similar finding emerged in analyses of qualitative data in North Carolina conducted in Barnes and Gennetian, 2021).27 Indeed, 61 percent of practitioners reported that Hispanic applicants learned about the TANF and related income assistance programs through word-of-mouth. Because applicants’ experiences are shared within the broader community, having offices that are perceived as a safe, welcoming space is even more important.

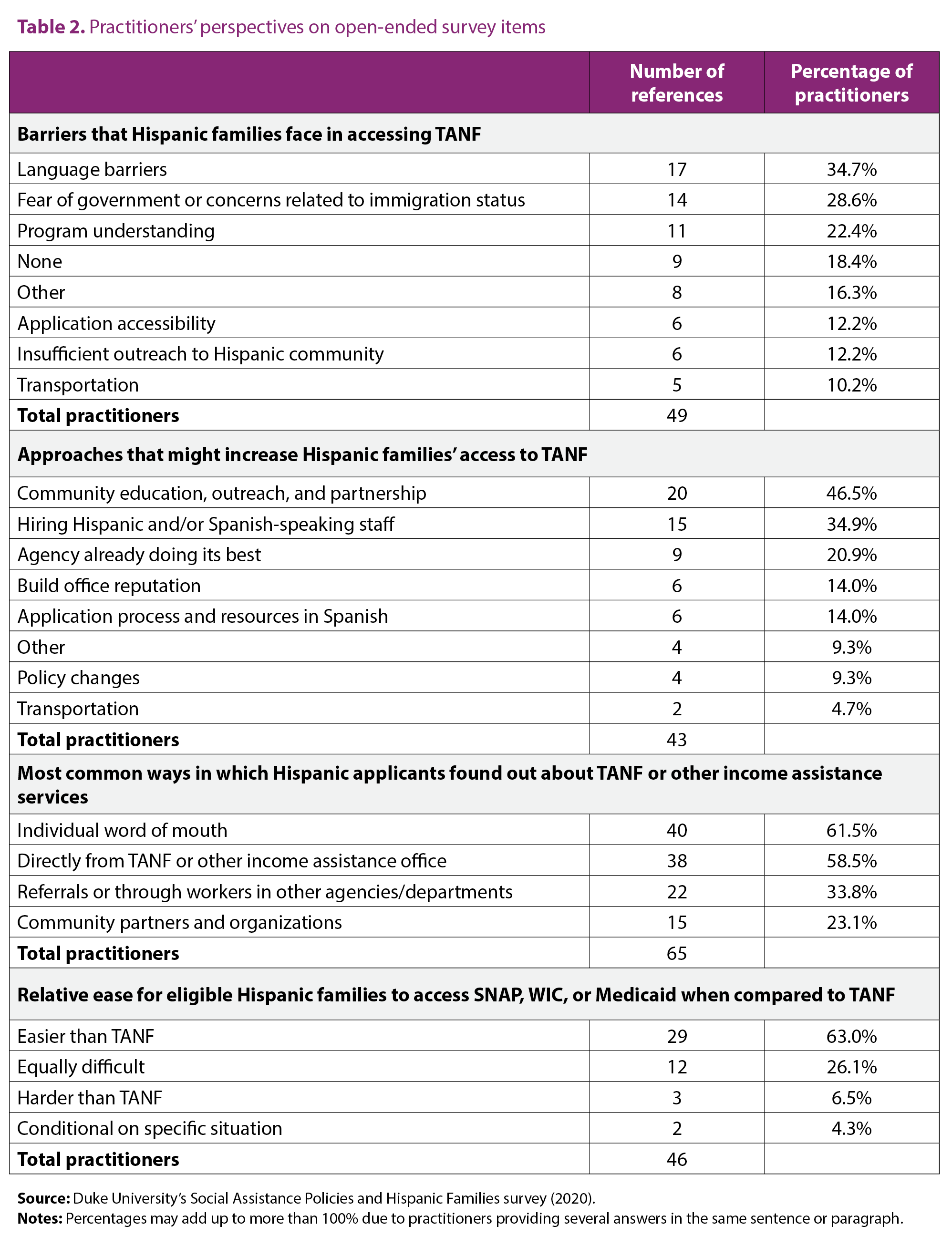

Additional practitioner insights from open-ended survey questions

Here, we supplement our analysis of practitioners’ responses to the questionnaire by examining their responses to the open-ended survey questions designed to elicit practitioner-identified barriers to access, recommendations on increasing access, and perceptions of how TANF compares to other social benefits such as SNAP, WIC, or Medicaid. Of the main sample, 65 practitioners answered the question on TANF service awareness among Hispanics, 49 answered the barriers question, 43 answered the recommendations question, and 46 answered the comparison question. Of the 66 practitioners that answered at least one open-ended question, 19 were frontline workers, 45 were administrators, and 2 did not indicate their job title. In contrast with the close-ended questions, we analyzed these answers for all practitioners combined to minimize sample size issues. The analyses performed for this section of the study identified patterns of responses and classified them into categories to gain more nuanced insights into the results from the previous section. Table 2 lists the findings that we will discuss below.

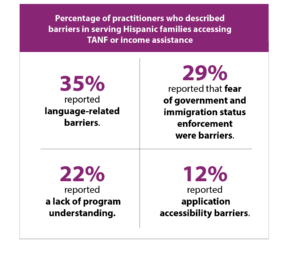

Approximately two thirds of providers felt that SNAP, WIC, or Medicaid were easier to access than TANF for Hispanic applicants.d Over three quarters indicated that Hispanic families faced some barriers to applying for TANF benefits, with language and immigration status reported most often as barriers. Other barriers included transportation, applicants’ uncertainty about whether they would find a welcoming environment, and an application process that clients may see as lengthy and taxing. Only 18 percent of practitioners reported that Hispanic families did not face any barriers. Specific barriers are included in the table below.

Practitioners also provided insight on strategies and approaches that might make it easier for Hispanic families to access TANF. In addition to community outreach and partnership, most recommendations involved creating more welcoming, safe-feeling spaces for Hispanic clients. Several practitioners suggested hiring more Hispanic staff to build their offices’ reputation in the community (for example, through word of mouth). Practitioners felt that they are doing their best to ease Hispanic families’ access to TANF, “given that policy does not allow applications any other way but face-to-face interview[s].” Some felt that the current process had evolved to allow more flexibility for clients to apply for TANF through other channels (besides in-person). Many felt that having “bilingual staff” and “easier access to translated applications and other supportive services” would make the application process easier to navigate for all Hispanics. Some practitioners mentioned that “the overall program is so very strict that it makes it difficult for families to always comply” and that “there is way too much paperwork required.” Practitioners also believe that an “increase in Spanish advertisements and pamphlets” would improve awareness around the TANF program’s offerings. Some indicated that TANF offices need to build relationships with applicants and clients, and that they need to “find a way to connect with Hispanic communities and build up the program’s reputation as a service where the intention is to assist individuals and households.” Other recommendations included providing transportation and employment services and coordinating better with other agencies. See the chart below for other recommendations.

Discussion of Implications

The perspectives and experiences of TANF and income assistance program practitioners are largely missing from policy discussions about providing services and benefits to families. Further, researchers previously understood little about how practitioners’ perspectives might vary when serving different populations. In this brief, we’ve taken a unique approach by reporting on the perspectives of income assistance program practitioners who serve Hispanic families in North Carolina.

As a Southern state with a growing Hispanic population, North Carolina’s income assistance practitioners can offer policy-relevant perspectives to help their peers in similar states understand Hispanics’ experiences and how they engage with income assistance. These insights are likely particularly relevant to North Carolina, but also to other states where program officials increasingly serve Latino families; as in North Carolina, practitioners in these states are striving to ensure that access and availability are equitable across populations who live under differing circumstances (English language and literacy proficiency, citizenship status, and feelings of safety and security amidst shifting anti-immigrant rhetoric and regulations).28

Using a survey distributed to county-level income assistance program administrators and frontline workers, we found that most of these practitioners believe that Hispanic clients have adequate access to on-demand interpreters, that there has been an increase in Spanish-language application materials over the last five years, and that Hispanic communities are well aware of the program services and resources offered by their local income assistance program office. However, we also found that administrators and frontline workers sometimes hold different views on matters such as the accessibility of Spanish-language application materials or the ease of navigating the application process for Latino applicants. Similar to our survey findings in New Mexico,29 our practitioner respondents articulated that the top three barriers to program access among Hispanics in North Carolina involve language barriers, fear of government and immigration-related concerns, and a lack of understanding about programs (including their goals and eligibility requirements). Practitioners also identified several opportunities to increase Hispanic families’ access to income assistance programs, including community education, outreach, and partnership.

Future work will offer a broader view across all 11 states, and will assess how these aspects of practitioner perspectives affect uptake of benefits among Latino families with children.

Survey Design and Methods

This brief draws from Duke University’s Social Assistance Policies and Hispanic Families survey to better understand how the design and implementation of income assistance policies shape Hispanic families’ experiences with safety net programs. The survey was administered online to TANF and related income assistance practitioners, including administrators and frontline workers in 11 states, including North Carolina. The questionnaire draws from many other well-established surveys and questionnaires, including work by Gaffney, Glosser, and Agoncillo (2018); Hahn Kassabian, Breslav, and Lamb (2015); and Heinrich et al. (2022).30,31,32 It also incorporates feedback from other subject matter experts, state representatives, and staff from the Administration for Children and Families in the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services. The survey content was further developed in consultations with experts (e.g., Elizabeth Lower-Basch, Peter Germanis, and Heather Hahn) and reviewed by the Steering Committee of the National Center for Research on Hispanic Children & Families. The survey collected information about organizational processes (language barriers, application processes, requested documentation), training and staff development, economic climate and budgetary constraints, demographics, office space, the welcomeness and physical safety of office spaces to TANF applicants, and the external political environment.

The North Carolina survey was fielded from June to September 2020, although responses filtered in through January 2021. It was distributed to all county social services administrators in the state via an existing listserv and sent out with a corresponding Dear County Director Letter. Administrators were asked to nominate frontline workers to receive the survey, too. A first reminder to complete the survey was sent in late August, with a direct follow-up in September for select practitioners in counties with a high share of Hispanic residents. The survey was voluntary and did not ask practitioners for any demographic information except for county of employment and job title.

In total, 78 practitioners from 49 counties across North Carolina—27 urban and 22 rural—consented to take the survey and submitted a response. Practitioner respondents were sorted into groups based on job titles, with a final sample of 52 administrators and 23 frontline workers. Three practitioners did not report a job title and were only included in the total count of responses. Data are available from an administrator and at least one frontline worker for only seven counties, which is too few to separately analyze. The counties represented in the survey varied in their percentages of Hispanic residents in the overall population, from 3 percent Hispanic in one county to 23 percent in another. Combined, the counties represented in the survey were home to approximately 78 percent of the state’s Hispanic population.

We use chi-squared significance tests to assess significant differences between the practitioner respondent groups: frontline staff and county administrators. In addition to the close-ended questions, 66 practitioners also answered four open-ended questions (40 practitioners fully responded to the open-ended questions and 26 did so partially) about the following: their views on barriers that Hispanic families face when accessing TANF; approaches that would facilitate access to the program; how TANF access compares to SNAP, WIC, or Medicaid; and how Hispanic clients discovered the TANF program. The thematic analysis of these questions was conducted using NVIVO and the coding was conducted independently by two researchers.

Footnotes

a We use “Hispanic and “Latino” interchangeably throughout the brief. Consistent with the U.S. Census definition, this includes individuals having origins in Mexico, Puerto Rico, and Cuba, as well as other “Hispanic, Latino or Spanish” origins.

b This brief complements Barnes and Gennetian (2021) and a recently released brief on New Mexico using data from the same survey.

c The specific survey item was: “Overall, I feel that my TANF program in 2019 was easy to navigate for the following Hispanic families,” with response options ranging from strongly agree=1 to strongly disagree = 5

d In North Carolina, applicants can apply to SNAP and Medicaid using ePass, which also shows program eligibility rules. For WIC, applicants must be physically present at the benefits office to apply, but eligibility rules can be found online as well.

Suggested Citation

Basurto, L., & Gennetian, L. (2022). Practitioners in North Carolina’s TANF and related income assistance programs offer perspectives on Latino families’ experiences. National Research Center on Hispanic Children & Families. https://doi.org/10.59377/672w1147z

Acknowledgements

The authors are grateful to Santiago Deambrosi, Jessica On, Carlos Gustavo Salas Flores, and Ana Paula Caruso for research assistance at multiple stages of this project. They would also like to acknowledge Carolyn Heinrich, Elizabeth Lower-Basch, Peter Germanis, and Heather Hahn for their contributions and substantive expertise on income assistance in the United States, especially during the earlier part of this effort with respect to survey design.

The authors would like to thank the Steering Committee of the National Research Center on Hispanic Children & Families—along with Julie Mendez, Kristen Harper, and Laura Ramirez—for their helpful feedback and edits, which significantly improved the manuscript. The Center’s Steering Committee is made up of the Center investigators—Drs. Natasha Cabrera (University of Maryland, Co-I), Danielle Crosby (University of North Carolina, Greensboro, Co-I), Lisa Gennetian (Duke University; Co-I), Lina Guzman (Child Trends, PI), Julie Mendez (University of North Carolina, Greensboro, Co-I), and Maria Ramos-Olazagasti (Child Trends, Building Capacity lead)—and federal project officers Drs. Ann Rivera, Jenessa Malin, and Mina Addo (Office of Planning, Research and Evaluation).

Last but not least, they would like to thank all those involved from the multiple state health and human services agencies or departments, especially to those who filled out the questionnaire. This analysis would not have been possible without their insight and collaboration.

Editor: Brent Franklin

Designer: Catherine Nichols

About the Authors

Luis E. Basurto is a research associate at the Center for Child and Family Policy working with Professor Lisa Gennetian. Mr. Basurto holds an MS in mathematics and statistics from Georgetown University, and an undergraduate degree in economics and finance from the University of Texas Rio Grande Valley.

His current work examines the health and economic well-being of Latino families and children, their experiences with poverty and social programs, and the impact of poverty reduction policies on families and children.

Lisa Gennetian, PhD, is a co-investigator of the National Research Center on Hispanic Children & Families, leading the research area on poverty and economic self-sufficiency. She is the Pritzker Professor of Early Learning Policy Studies at Duke University Sanford School of Public Policy. One of her research foci is income instability among children and families, the ways this is informed by theories emerging from behavioral economics, and implications for social policy and programs.

About the Center

The National Research Center on Hispanic Children & Families (Center) is a hub of research to help programs and policy better serve low-income Hispanics across three priority areas: poverty reduction and economic self-sufficiency, healthy marriage and responsible fatherhood, and early care and education. The Center is led by Child Trends, in partnership with Duke University, University of North Carolina at Greensboro, and University of Maryland, College Park. The Center is supported by grant #90PH0028 from the Office of Planning, Research, and Evaluation within the Administration for Children and Families in the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services.

The National Research Center on Hispanic Children & Families is solely responsible for the contents of this brief, which do not necessarily represent the official views of the Office of Planning, Research, and Evaluation, the Administration for Children and Families, or the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services.

Copyright 2022 by the National Research Center on Hispanic Children & Families.

References

1 National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine. 2019. A Roadmap to Reducing Child Poverty. Washington, DC: The National Academies Press. https://doi.org/10.17226/25246

2 Herd, P., & Moynihan, D. P. (2018). Administrative Burden: Policymaking by Other Means. Russell Sage Foundation. https://doi.org/10.7758/9781610448789

3 McDaniel, M., Woods, T., Pratt, E., & Simms, M. (2017). Identifying racial and ethnic disparities in human services: A conceptual framework and literature review. Washington, DC: Urban Institute. https://www.urban.org/research/publication/identifying-racial-and-ethnic-disparities-human-services

4 Hill, Z., Gennetian, L., & Mendez, J. (2019). A Descriptive Profile of State Child Care and Development Fund Policies in States with high populations of low-income Hispanic children. Early Childhood Research Quarterly, 47, 111-123. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ecresq.2018.10.003

5 Herd, P., & Moynihan, D. P. (2018). Administrative Burden: Policymaking by Other Means. Russell Sage Foundation. https://doi.org/10.7758/9781610448789

6 McDaniel, M., Woods, T., Pratt, E., & Simms, M.C. (2017). Identifying Racial and Ethnic Disparities in Human Services: A Conceptual Framework and Literature Review. OPRE Report #2017-69. Washington, D.C.: Urban Institute. https://www.urban.org/research/publication/identifying-racial-and-ethnic-disparities-human-services

7 Bitler, M., Gennetian, L., Gibson-Davis, C., Rangel, M. A. (2021). Means-Tested Safety Net Programs and Hispanic Families: Evidence from Medicaid, SNAP, and WIC. The ANNALS of the American Academy of Political and Social Science, 696(1), 274-305. https://doi.org/10.1177%2F00027162211046591

8 Bernstein, H., McTarnaghan, S., Islam, A. (2021). Centering Race and Structural Racism in Immigration Policy Research: Considerations and Lessons from the field. Washington, D.C.: Urban Institute. Retrieved from https://www.urban.org/research/publication/centering-race-and-structural-racism-immigration-policy-research

9 Gennetian, L., Tienda, M. (2021). Investing in Latino Children and Youth: Volume Introduction and Overview. The ANNALS of the American Academy of Political and Social Science, 696(1), 6-17. https://doi.org/10.1177%2F00027162211049760

10 Tippet, R. (2021). North Carolina’s Hispanic Community: 2021 Snapshot: North Carolina’s Hispanic population is now greater than one million people. Carolina Demography. https://www.ncdemography.org/2021/10/18/north-carolinas-hispanic-community-2021-snapshot/

11 Rosenthal, J. (2021). Hispanic Heritage Month 2021. North Carolina Department of Commerce. https://www.nccommerce.com/blog/2021/10/12/hispanic-heritage-month-2021

12 U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics (2022). Demographic Characteristics (CPS). https://www.bls.gov/cps/demographics.htm#race

13 U.S. Census Bureau. (2020). Employment Status, 2016-2020 American Community Survey 5-Year Estimates. https://data.census.gov/cedsci/table?q=labor%20force%20participation%20rate&g=0400000US37&tid=ACSST5Y2020.S2301

14 U.S. Census Bureau (2019). Poverty Status In The Past 12 Months By Age (Hispanic Or Latino), 2019 American Community Survey 1-Year Estimates. https://data.census.gov/cedsci/table?q=poverty%20by%20hispanic&g=0400000US37&tid=ACSDT1Y2019.B17020I

15 U.S. Census Bureau. (2019). Selected Characteristics Of People At Specified Levels Of Poverty In The Past 12 Months, 2019 American Community Survey 1-Year Estimates. https://data.census.gov/cedsci/table?q=poverty&g=0400000US37&tid=ACSST1Y2019.S1703

16 North Carolina Department of Health and Human Services (2022). Work First Family Assistance. https://www.ncdhhs.gov/divisions/social-services/work-first-family-assistance

17 North Carolina Department of Health and Human Services (2022). What is ePASS?. https://cms9files.revize.com/martincountync/Document%20Center/Department/Social%20Services/Forms%20&%20Documents/ePASS%20Factsheet.pdf

18 Barnes, C. Y., & Henly, J. R. (2018). “They are underpaid and understaffed”: How clients interpret encounters with street-level bureaucrats. Journal of Public Administration Research and Theory, 28(2), 165-181. https://academic.oup.com/jpart/article/28/2/165/4885362

19 Pratt, E., & Hahn, H. (2021). What Happens When People Face Unfair Treatment or Judgment When Applying for Public Assistance or Social Services? Washington, DC: Urban Institute. https://www.urban.org/research/publication/what-happens-when-people-face-unfair-treatment-or-judgment-when-applying-public-assistance-or-social-services

20 Riccucci, N. M., Meyers, M. K., Lurie, I., & Han, J. S. (2004). The implementation of welfare reform policy: The role of public managers in front‐line practices. Public Administration Review, 64(4), 438-448.

21 Riccucci, N. M. (2005). Street-level bureaucrats and intrastate variation in the implementation of temporary assistance for needy families policies. Journal of Public Administration Research and Theory, 15(1), 89-111.

22 May, P. J., & Winter, S. C. (2009). Politicians, managers, and street-level bureaucrats: Influences on policy implementation. Journal of Public Administration Research and Theory, 19(3), 453-476.

23 Bell, E., & Smith, K. (2022). Working Within a System of Administrative Burden: How Street-Level Bureaucrats’ Role Perceptions Shape Access to the Promise of Higher Education. Administration & Society, 54(2), 167–211. https://doi.org/10.1177/00953997211027535

24 Moynihan, D., Herd, P., & Harvey, H. (2015). Administrative burden: Learning, psychological, and compliance costs in citizen-state interactions. Journal of Public Administration Research and Theory, 25(1), 43-69.

25 Gaffney, A., Webster, R. (2021). Promoting a Positive Organizational Culture in TANF Offices. OPRE Report 2021-51. Washington, DC: Office of Planning, Research, and Evaluation, Administration for Children and Families, U.S. Department of Health and Human Services. https://www.acf.hhs.gov/sites/default/files/documents/opre/promoting%20a%20positive%20organizational%20culture_april%202021_508QC.pdf

26 National Immigration Law Center (n.d.). Know Your Rights. https://www.nilc.org/get-involved/community-education-resources/know-your-rights/

27 Barnes, C. & L.A. Gennetian (2021). Experiences of Hispanic families with social services in the racially segregated southeast. Race and Social Problems. Special issue on Race, Child Welfare, and Child Wellbeing. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12552-021-09318-3

28 North Carolina Department of Health and Human Services (2022). Strategic Goals. https://www.ncdhhs.gov/about/dhhs-mission-vision-values-and-goals

29 Finno-Velasquez, M., Gennetian, L., Sepp, S., & Deambrosi, S. (2021). Practitioners in New Mexico’s TANF Program Offer Perspectives on Engaging Hispanic Families. Report 2021-03. Bethesda, MD: National Research Center on Hispanic Children & Families. www.hispanicresearchcenter.org/research-resources/practitioners-in-new-mexicos-tanf-program-offer-perspectives-on-engaging-hispanic-families

30 Gaffney, A., Glosser, A., & Agoncillo, C. (2018). Organizational culture in TANF offices: A review of the literature (OPRE Report 2018-116). Washington, DC: U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, Administration for Children and Families, Office of Planning, Research and Evaluation. https://www.acf.hhs.gov/opre/report/organizational-culture-tanf-offices-review-literature

31 Hahn, H., Kassabian, D., Breslav, L., & Lamb, Y. (2015). A descriptive study of county-versus state administered Temporary Assistance for Needy Families programs. Washington, DC: Urban Institute. https://www.urban.org/research/publication/descriptive-study-county-versus-state-administered-temporary-assistance-needy-families-programs

32 Heinrich, C. J., Camacho, S., Henderson, S. C., Hernández, M., & Joshi, E. (2022). Consequences of Administrative Burden for Social Safety Nets that Support the Healthy Development of Children. Journal of Policy Analysis and Management, 41(1), 11-44. https://doi.org/10.1002/pam.22324

Appendix

Copyright 2025 by the National Research Center on Hispanic Children & Families.

This website is supported by Grant Number 90PH0032 from the Office of Planning, Research & Evaluation within the Administration for Children and Families, a division of the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services totaling $7.84 million with 99 percentage funded by ACF/HHS and 1 percentage funded by non-government sources. Neither the Administration for Children and Families nor any of its components operate, control, are responsible for, or necessarily endorse this website (including, without limitation, its content, technical infrastructure, and policies, and any services or tools provided). The opinions, findings, conclusions, and recommendations expressed are those of the author(s) and do not necessarily reflect the views of the Administration for Children and Families and the Office of Planning, Research & Evaluation.