Sep 22, 2022

Research Publication

Child Care Subsidy Staff Share Perspectives on Administrative Burden Faced by Latino Applicants in North Carolina

Authors:

This is an abbreviated version of the complete study. To read the full version, download the PDF.

Through the federal Child Care and Development Fund (CCDF), states administer child care subsidy programs to support low-incomea parents’ employment and expand children’s access to high-quality child care. Many Hispanicb children stand to benefit from this key public investment,1 given that most live with an employed parent2 and more than half live in low-income households.3 Still, Latino families are generally less likely to use many forms of public assistance4 and are underrepresented among child care subsidy recipients.5

Policy features and administrative practices are important levers in facilitating or restraining access to programs including child care subsidies.6 Federal CCDF guidelines provide states with considerable flexibility in setting rules, policies, and procedures related to child care subsidies, including those related to eligibility criteria, documentation requirements, and the application and waitlist processes.7 Hill, Gennetian, and Mendez8 previously described how several state CCDF policy choices on these dimensions determined at the state or local levels can differentially affect Hispanic parents’ access to child care subsidies.

In this brief, we extend the Hill et al. analysis by examining how CCDF policies are interpreted and implemented on the ground by local caseworkers and administrators who work directly with families seeking subsidies. To assess how state and local CCDF contexts may contribute to administrative burden for Hispanic applicants, we conducted an online survey of county-level subsidy agency supervisors and frontline caseworkers. We compared on-the-ground practices of local child care subsidy staff to state-level policy and guidance documents highlighting cases where practices align or diverge from documented policies and discuss the implications of this for Latino families’ access to child care subsidies.

Key Findings

Local subsidy staff in North Carolina utilized a range of administrative practices when assisting families with the subsidy application process, and their perceptions of qualifying activities, prioritized populations, documentation requirements, and the language accessibility of program materials varied widely. Reported implementation practices reveal some inconsistencies with documented state-level policies and guidance. While some local subsidy staff practices may facilitate eligible Hispanic families’ access to child care subsidies, others are likely to increase administrative burden and restrict access.

Qualifying activities for child care subsidy eligibility

- All local subsidy staff identified employment as an approved activity; most (80% or more) considered education, job training, and activities related to the Temporary Assistance to Needy Families (TANF) program to be approved; and fewer (60% to 70%) considered job search and activities related to the Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program (SNAP) to be approved. According to state policy documents, though, all these activities qualify a family to receive assistance.

- On the other hand, most subsidy staff considered English as a Second Language (ESL) classes and housing search for homeless families to be qualifying activities, even though these are not described as eligible activities in state policy documents.

- In terms of the prevalence of different qualifying activities, most subsidy staff reported that employment, education, and TANF-related activities are common across the families they serve. In addition, just more than half reported job search and job training activities as common, and roughly one quarter reported SNAP-related activities, ESL classes, and housing search as common.

Prioritized applicant groups

- Most local subsidy staff (87%) said that, given limited funding, their office prioritizes certain applicants. Staff members’ most commonly identified priority groups—children in child protective services (77%), children in foster care (63%), families in the TANF income assistance program (53%), children who are homeless (41%), and children with disabilities (36%)—align with those identified as prioritized populations in state policy documents, although there was variation in how consistently these groupings were endorsed across staff.

Required or requested documents as part of the application process

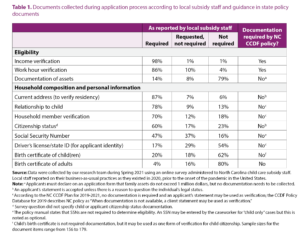

- Consistent with state policy, nearly all local subsidy staff reported that documents verifying income (98%) and work hours (86%) are required as part of the subsidy application.

- Most subsidy staff said they also require or request other documents from applicants that are not explicitly required by state policy but are left to local subsidy staff’s discretion. Most staff reported requiring or requesting documentation verifying applicants’ home address (87% require, 7% request), relationship to the child (78% require, 9% request), household membership (70% require, 12% request), citizenship status (60% require, 17% request), and Social Security Number (47% require, 37% request). Fewer than half of surveyed staff said they require or request driver’s licenses, birth certificates, or documentation of household assets.

- More than half (57%) of local subsidy staff reported that, in their experience, applicants have difficulty providing one or more types of documentation. They report the most challenging documents to be those verifying income, work hours, citizenship status, and Social Security Numbers, with the latter two reported to be especially difficult for Latino applicants.

Language accessibility of program information and resources

- More than half of the staff surveyed said that program information and resources are generally available in Spanish for in-person settings but are less accessible online. Most subsidy staff also reported having access to Spanish translation and interpreter services when needed, either on-site (58%) or by phone (76%). Only a small percentage of staff (roughly 5%) described themselves as fluent in Spanish.

- According to local staff, supports for families speaking Indigenous languages from Latin America were far less available than those for Spanish-speaking families. Fewer than 20 percent said program information or application materials exist in any Indigenous language. Roughly 20 percent reported having access to translation or interpreter services on-site to support communication with families who speak an Indigenous language, although more than 40 percent felt they could access these services by phone if needed.

Variation in local subsidy staff perspectives and experiences by role

- Responses were generally similar across frontline subsidy staff and local agency administrators. The few statistically significant differences by role indicated the following:

- Administrators were more likely than frontline workers to identify TANF recipients and employed parents as prioritized groups.

- Administrators and frontline workers were equally likely to describe one or more documents as challenging for applicants. However, administrators were less likely than frontline workers to perceive challenges related to work hours, income, home address, and citizenship verification.

- Administrators described some Spanish and Indigenous language supports as more accessible than did frontline workers.

Defining the Roles of CCDF Staff

Specific job titles, and their functions, can vary across North Carolina counties and benefit systems. As described in this brief, frontline workers are those responsible for assisting families and processing applications for child care subsidies, and administrators provide oversight and management functions. In some counties, the same person could identify as an administrator and a frontline worker. We use “local subsidy staff” as an inclusive term for both of these job functions within county offices, while recognizing that other terms—including “practitioner” or “specialist”—are often used to describe an employee who engages with families to determine eligibility for government assistance programs.

Conclusion

Our findings suggest that subsidy administration practices “on the ground” sometimes vary from state policies as they are “on the books” in ways that may exacerbate administrative exclusion8 and constrain low-income Hispanic parents’ access to child care assistance. While some staff-reported practices could be considered more facilitative of access than official state policy, many staff described practices that likely create a more restrictive environment for Latino families and create administrative burden.6

Our survey results suggest documentation as a key area where many local subsidy caseworkers and administrators engage in more restrictive practices than exist in official state policy. Consistent with North Carolina’s effort to streamline the verification process to improve access,9 official state policy requires documentation primarily only for work hours and income. Yet, a majority of local subsidy staff reported to us that they require or request a range of other documents from applicants.

Future research should examine factors that can facilitate caseworkers’ selection of more inclusive versus restrictive practices. For example, technical support and professional development for caseworkers and local administrators, especially in locations with high Hispanic growth, may support greater use of more equitable procedures during the application process and help increase access for Latino families. Researchers could also partner with state agencies to help identify and test strategies for reducing administrative burden for Hispanic populations.

Related Research on Policy Implementation

Related research involving the analysis of administrative burden with Hispanic populations are available for the Child Care and Development Fund (CCDF) child care subsidy program and Temporary Assistance to Needy Families (TANF) income assistance programs, both across and within multiple state contexts.

Footnotes

a Low-income households are consistently defined in research, and in this brief, as those with incomes below twice the federal poverty threshold adjusted for family size. For an example of this indicator, see the Annie E. Casey Foundation Kids Count Data Center, Low-income working families with children.

b We use “Hispanic” and “Latino” interchangeably throughout the brief. Consistent with the U.S. Census definition, this includes individuals having origins in Mexico, Puerto Rico, and Cuba, as well as other “Hispanic, Latino, or Spanish” origins.

References

1Mendez, J., Crosby, D., & Stephens, C. (2021). Equitable access to high-quality early care and education: Opportunities to better serve young Hispanic children and their families. In L. Gennetian & M. Tienda (Eds), Investing in Latino Youth. Annals of the American Academy of Political and Social Science (AAPSS). Sage. DOI: 10.1177/00027162211041942

2Turner, K., Guzman, L., Wildsmith, E., & Scott, M. (2015). The complex and varied households of low-income Hispanic children. Child Trends. https://www.childtrends.org/publications/the-complex-and-varied-households-of-low-income-hispanic-children

3Koball, H., Moore, A., & Hernandez, J. (2021). Basic Facts about Low-Income Children: Children Under 18 Years, 2019. National Center for Children in Poverty. https://www.nccp.org/wp-content/uploads/2021/03/NCCP_FactSheets_All-Kids_FINAL-1.pdf

4Williams, S. (2013). Public Assistance Participation among U.S. Children in Poverty, 2010 (FP-13-02). National Center for Family & Marriage Research. https://www.bgsu.edu/content/dam/BGSU/college-of-arts-and-sciences/NCFMR/documents/FP/FP-13-02.pdf

5Hill, Z., Gennetian, L. A., & Mendez, J. (2019a). How State Policies Might Affect Hispanic Families’ Access to and Use of Child Care and Development Fund Subsidies. https://www.hispanicresearchcenter.org/research-resources/how-state-policies-might-affect-hispanic-families-access-to-and-use-of-child-care-and-development-fund-subsidies/

6Brodkin, E. Z. & Majmundar, M. (2010). Administrative exclusion: Organizations and the hidden costs of welfare claiming. Journal of Public Administration Research and Theory, 20 (4), 827-848.

7Office of Child Care. (2021). History and Purposes of the CCDGB and CCDF. U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, Administration for Children and Families. https://childcareta.acf.hhs.gov/ccdf-fundamentals/history-and-purposes-ccdbg-and-ccdf

8Hill, Z., Gennetian, L. A., & Mendez, J. (2019b). A descriptive profile of state Child Care and Development Fund policies in states with high populations of low-income Hispanic children. Early Childhood Research Quarterly, 47(2), 111-123.

9Isaacs, J.B., Katz, M., & Kassabian D. (2016). Changing Policies to Streamline Access to Medicaid, SNAP, and Child Care Assistance: Findings from the Work Support Strategies Evaluation. Washington, DC: Urban Institute.