May 1, 2024

Research Publication

More Than 6 in 10 Hispanic Children’s Households Experienced Material Hardship in 2020

Authors:

Overview

When families are able to meet their basic needs, they experience less stress and are better able to support their children1 and help them thrive. For many Hispanica families, experiences of material hardship are common, with roughly half of Hispanic households with children reporting any degree of material hardship.2 Researchers define material hardship as the “direct indicators of consumption and physical living conditions to examine whether families meet certain basic needs.”3

Research shows that measures of material hardship4—which most often assess a family’s ability to meet their housing, bill-paying, food, and medical needs—are independently meaningful5 and provide a useful complement to poverty measures6 when assessing a family’s economic well-being.b In fact, prior research has found that 75 percent of households reporting any material hardship had incomes above the official poverty threshold.7 Additionally, it is important to look at multiple dimensions of material hardship, which are only modestly correlated with one another8 and can impact child well-being in different ways.

This brief uses data from the 2021 Survey of Income and Program Participation (SIPP) to provide descriptive estimates of household-level material hardship among Latino children under age 18 in 2020, the year when COVID-19 emerged in the United States. Latinx families were among the hardest hit by COVID, both health-wise (they faced some of the highest rates of disease burden and COVID-related mortality)9 and socioeconomically (via job loss10 and reduction in work hours).11 We show data on four hardship measures—housing quality hardship, bill-paying hardship, food insecurity, and (an indirect measure of) medical hardship (see below for a deeper discussion of the material hardship measures used in this brief)—indicating the percentage of children whose households were sometimes unable to meet their needs. We look at these four domains individually and cumulatively, showing the percentage of children whose households were experiencing any of the domains of hardship, in addition to how many domains they experienced. Notably, we examine how experiences of material hardship varied within the Latino child population by parental birth within or outside the United States, household poverty status, and family structure12—all sociodemographic factors that are correlated with a family’s access to resources and support, including from publicly funded programs.

The analyses in this brief will shed light on the type and depth of household material hardship faced by diverse Hispanic children; in turn, this knowledge can supplement our understanding of the economic disadvantage families face and inform programmatic approaches to working with families.

Key Findings

Overall, most (62%) Hispanic children were in a household that experienced at least one of the four domains of material hardship in 2020. Experiencing at least one domain of hardship was more common among Hispanic children who lived in households with incomes below (82% of children in these households) or near (70%) the poverty thresholdc and among those living with at least one parent born outside of the United States (66%). Notably, half (50%) of Hispanic children in households not classified as having low incomes experienced at least one household material hardship domain in 2020.

Of the material hardship domains we examined, medical hardship was the most frequently reported. More than twice as many Latinx children lived in a household that reported medical hardship in the past year (43%)—that is, they had at least one parent without health insurance and/or had a parent with unpaid medical debt—than in a household reporting food insecurity (18%), housing quality hardship (20%), or bill-paying hardship (18%).

- Hispanic children in households with incomes below or near the poverty threshold and those living with one parent were more likely than other children to live in households experiencing each of the four measured domains of material hardship (food insecurity, housing quality hardship, bill-paying hardship, and medical hardship).

- Hispanic children living with a parent born outside the United States were more likely than those with U.S.-born parents to be in a household experiencing medical hardship or food insecurity.

Regarding co-occurring hardships, roughly one quarter of Latino children lived in households reporting two or more hardship domains (16% with two hardships and 9% with three or four). Just over one third of Latino children (37%) lived in households reporting only one of the hardship domains.

There was variation in co-occurring hardships across the socio-demographic characteristics we examined. For example, similar proportions of Latinx children, regardless of their household’s income status, reported one hardship (just over one third, or 36% to 38% depending on household income). However, Latinx children living in households with incomes below the poverty threshold were almost five times more likely to experience three or four hardships (18%) than those in households with incomes above 200 percent of the poverty threshold (4%).

Measuring Material Hardship in the SIPP

The measures of material hardship in this analysis include the three core domains of food insecurity, housing quality hardship, and bill-paying hardship that are commonly used13 in research and explicitly captured with the most recent waves of the SIPP.14 Research using SIPP data prior to 2014 also frequently examined the domain of medical15 or health14 hardship, captured with measures indicating whether someone did not receive medical or dental care in the past year because of cost. Unfortunately, these questions were removed from the SIPP when the survey was redesigned in 2014. As a result, this brief uses measures that indirectly tap into the domain of medical hardship. Medical hardship includes information on two factors associated with an inability to access needed medical care16 or the decision to forgo medical care17—health insurance coverage and unpaid medical debt. This conceptualization of medical hardship is also informed by recent expert recommendations to identify having health insurance as a basic need18 and to incorporate unpaid medical debt19 into measures of financial hardship,20 as well as other emerging research that explicitly uses medical debt as an indicator of medical hardship.21

The four domains of material hardship that we examine are available in the 2021 SIPP data and were asked of respondents about the 2020 calendar year.d Even within these core domains, there is variability in how material hardship is measured, and some domains are multi-dimensional. For example, the measure of housing quality hardship22 used in the SIPP captures the quality of the housing environment in which children live and has been linked to a range of child outcomes,23 including health, education, and even engagement with child social services. Additionally, the measure of bill-paying hardship includes trouble paying bills and/or a mortgage or rent payment. Trouble paying a mortgage or rent payment can also be an indicator of housing hardship.

Below, we detail how we measure the four domains of material hardship included in this analysis.

Food insecurity is a well-validated USDA scale24 that captures whether a household reported medium or high food insecurity, which happens when at least two of the five following statements were reported as true in the past year:

- Did the food you bought not last often/sometimes?

- Could you not afford balanced meals often/sometimes?

- Did you ever cut the size of your meals or skip meals because there wasn’t enough money for food?

- Did you ever eat less than you felt you should because there wasn’t enough money to buy food?

- Were you ever hungry but didn’t eat because there wasn’t enough money for food?

Bill-paying hardship captures whether a child lives in a household that reported being unable to pay their utility bills and/or their rent or mortgage in the past year.

Housing quality hardship captures whether a child lives in substandard housing, which is determined by whether a household reported yes to any of the following statements:

- Is there a problem with pests?

- Are there plumbing problems?

- Are there holes in the floor?

- Are there cracks in the ceiling or walls?

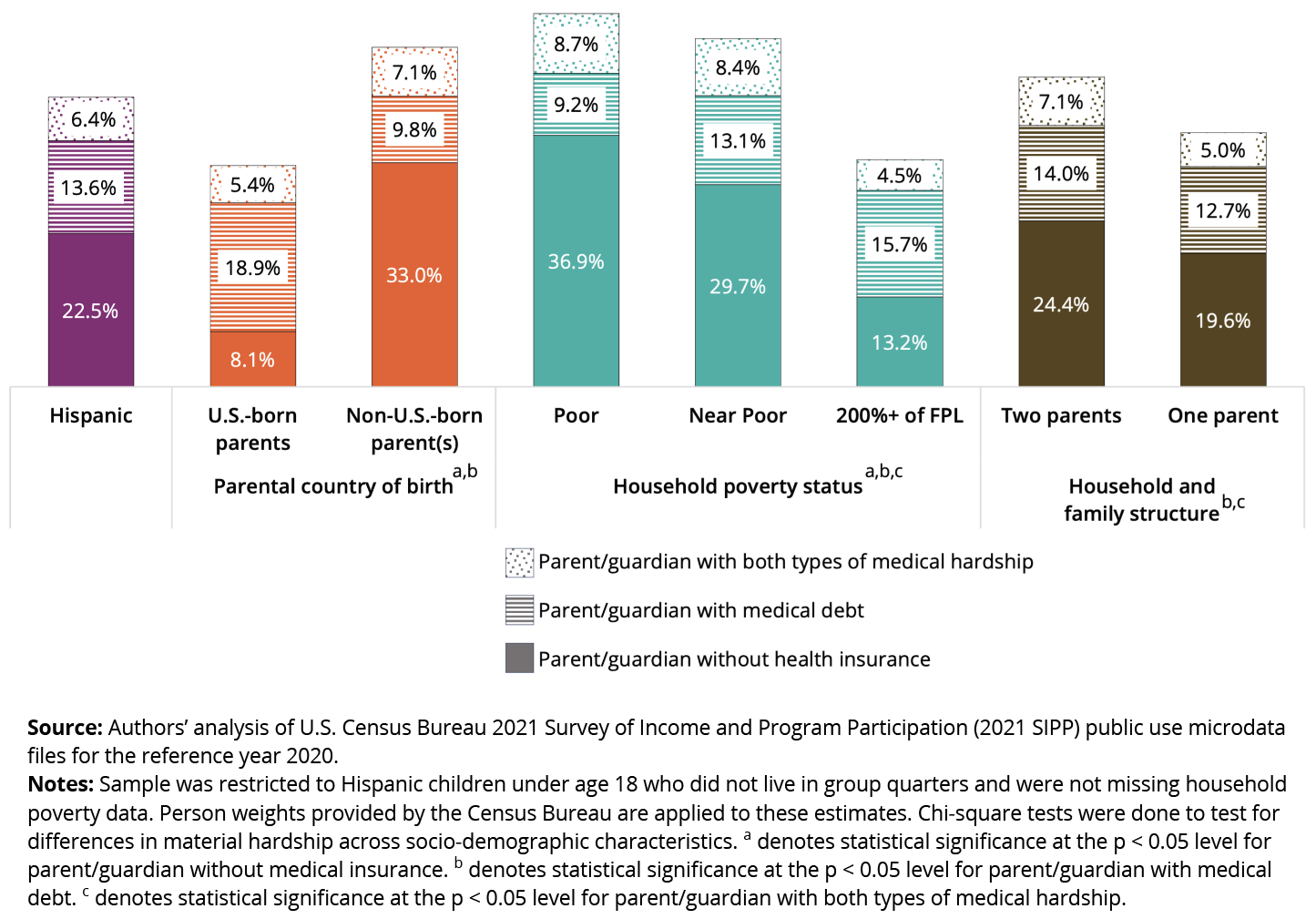

Medical hardship indicates whether a child lived in a household that reported having unpaid medical debt and/or whether at least one coresident parent/guardian was without health insurance in the past year. Because this measure is not well established in the field, we show medical hardship overall, but also note whether the hardship is the result of medical debt, a lack of health insurance, or both.

Findings

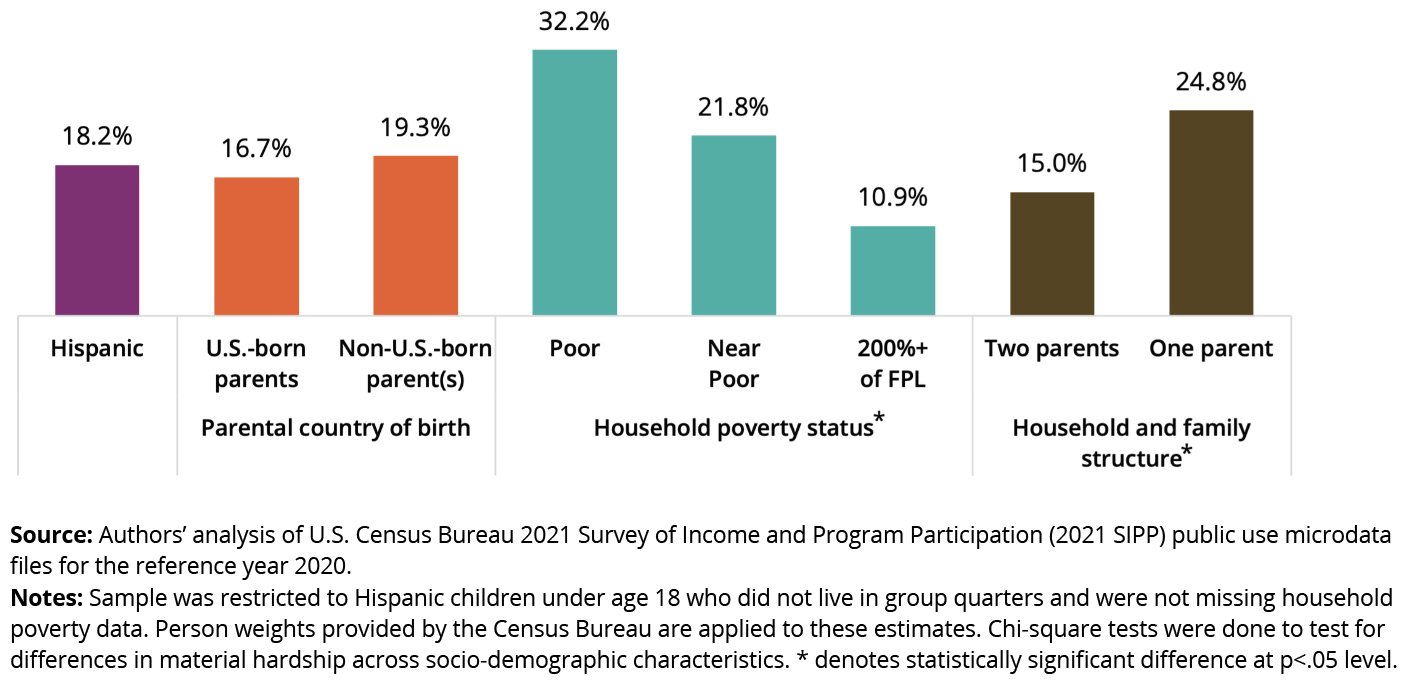

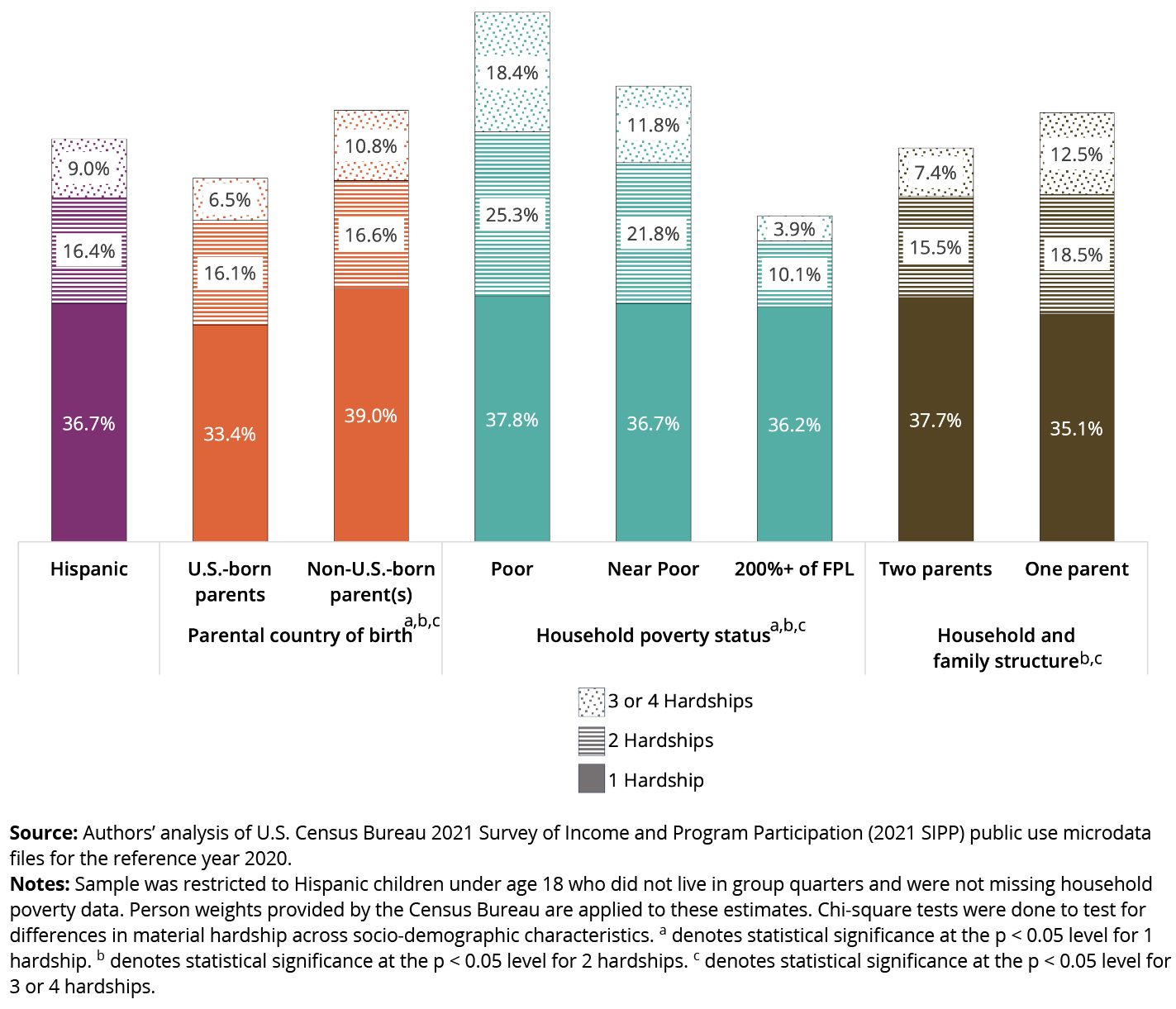

Figures 1 to 4 show the 2020 prevalence of household-level material hardship among Hispanic children. We show results separately for the four domains of hardship included in this analysis—food insecurity (Figure 1), housing quality hardship (Figure 2), bill-paying hardship (Figure 3), and medical hardship (Figure 4). Each figure shows the prevalence among all Hispanic children, as well as separately by parents’ birth within or outside the United States (U.S.-born and foreign-born); household poverty status (<100% of the federal poverty level [FPL; poor], 100-199% of FPL [near poor], and >200% of the FPL); and family structuree (one-parent vs. two-parent household). See Table A1 for the distribution of the sample across sociodemographic characteristics. Figure 5 shows the proportion of Hispanic children who faced one, two, and three or four of these hardship domains in 2020. See Table A2 for the data used to construct Figures 1-5.

Food insecurity

As shown in the first column of Figure 1, 18 percent of Latino children lived in a household that reported experiencing food insecurity at some point in 2020. However, there was quite a bit of variability in this experience across the sociodemographic factors we examined.

- Parent birth within or outside the United States. In 2020, Latinx children who lived in households with at least one parent born outside of the United States were more likely to be in households that experienced food insecurity in the past year (19%) than those whose parents were both U.S.-born (15%).

- Poverty status. Nearly one third (32%) of Hispanic children who lived in households with incomes below the poverty threshold experienced food insecurity in 2020, compared to just under one quarter of children (23%) living in households with incomes near poverty (100-200% of the poverty threshold) and less than 1 in 10 children (9%) in households with incomes above 200 percent of the poverty threshold.

- Family structure. In 2020, one quarter of Latino children living with one coresident parent were in a household that reported food insecurity in the past year; this is 70 percent higher than the percentage of children living in two-parent families (15%).

Figure 1. Eighteen percent of all Hispanic children, and nearly one third of those living in households with incomes below the poverty threshold, live in a household that reported experiencing food insecurity

Percentage of Hispanic Children living in a household that reported experiencing food insecurity at some point in the past year, overall, and by parental birth within or outside of the United States, poverty status, and family structure, 2020

Housing quality hardship

The first column of Figure 2 shows that, in 2020, one in five Latinx children (20%) lived in a household reporting some form of housing quality hardship. Again, there was variability in the experience of housing quality hardship among Hispanic children across the sociodemographic factors we examined.

- Parent birth within or outside the United States. In contrast to food insecurity, in 2020, Hispanic children who lived in a household with at least one parent born outside of the United States were statistically no more likely to be in a household experiencing housing quality hardship than those whose parents were U.S.-born.

- Poverty status. However, as with food insecurity, housing quality hardship in 2020 varied by poverty status. Latino children living in households with incomes below or near the poverty threshold were significantly more likely to experience housing quality hardship (28% and 23%, respectively) than those in households with higher incomes (16%).

- Family structure. More than one quarter (26%) of Hispanic children living with one parent were in a household that reported some form of housing quality hardship in 2020, compared to 17 percent of Hispanic children living with two parents.

Figure 2. Twenty percent of all Hispanic children, and 28 percent of those living in households with incomes below the poverty threshold, live in a household that reported experiencing housing quality hardship

Percentage of Hispanic children living in a household that reported experiencing housing quality hardship at some point in the past year, overall, and by parental birth within or outside of the United States, poverty status, and family structure, 2020.

Bill-paying hardship

The first column of Figure 3 shows that, in 2020, 18 percent of Latino children lived in a household that reported trouble paying for utilities or their rent or mortgage in the past year.

- Parent birth within or outside the United States. In 2020, Hispanic children who lived in households with at least one parent born outside of the United States were statistically no more likely to be in households experiencing bill-paying hardship—although their percentage was slightly higher—relative to those with U.S.-born parents.

- Poverty status. However, bill-paying hardship varied by poverty status in 2020. Nearly one third (32%) of Latino children living in households with incomes below the poverty threshold were in a household that experienced bill-paying hardship, compared to 22 percent living in households with incomes near poverty and just over 1 in 10 children (11%) in households with incomes above 200 percent of the poverty threshold.

- Family structure. Nearly one quarter (25%) of Latinx children living with one parent in 2020 were in a household that reported some form of bill-paying hardship, compared to 15 percent of Hispanic children living with two parents.

Figure 3. Eighteen percent of all Hispanic children, and nearly one third of those living in households with incomes below the poverty threshold, live in a household that reported experiencing bill paying hardship

Percentage of Hispanic children living in a household that reported experiencing bill-paying hardship at some point in the past year, overall, and by parental birth within or outside of the United States, poverty status, and family structure, 2020.

Medical hardship

In 2020, parental medical hardship was much more prevalent among Hispanic children than the other measures of hardship examined in this brief. The first column of Figure 4 shows that more than 4 in 10 (43%) Hispanic children lived in a household that reported unpaid medical debt and/or at least one parent without health insurance. Just over 6 percent of Latino children lived in households with both types of hardship, while 23 percent faced only insurance hardship and 14 percent faced only medical debt. There was substantial variation in reports of medical hardship—and in this domain’s more specific dimensions—within the Hispanic child population across the sociodemographic measures we examined.

- Parent birth within or outside the United States. In 2020, approximately half (50%) of Hispanic children with at least one parent born outside of the United States lived in a household that reported experiencing medical hardship in the past year (most often a lack of health insurance), compared to one third (32%) of Hispanic children with U.S.-born parents (most often unpaid medical debt).

- Poverty status. Over half of Latinx children living in households with incomes below (55%) or near the poverty threshold (51%) in 2020 had parent(s) in households that reported experiencing medical hardship (most often a lack of health insurance), compared to one third (33%) living in households with incomes above 200 percent of the poverty threshold (most often unpaid medical debt).

- Family structure. In 2020, Latino children living with two parents reported more medical hardship (45.5%) than those living with one parent (37%). In both family types, a lack of health insurance was the most common hardship.

Figure 4. Forty-three percent of all Hispanic children, and more than half of those living in households with incomes below the poverty threshold, live in a household that reported experiencing medical hardship.

Percentage of Hispanic children living in a household that reported experiencing medical hardship at some point in the past year, overall, and by parental birth within or outside of the United States, poverty status, and family structure, 2020.

Cumulative hardship

Figure 5 depicts cumulative reports of material hardship across all four domains examined. Specifically, it shows the percentage of Latinx children who lived in a household experiencing one, two, or three or four of the hardship domains we included in this analysis at some point in 2020.f

Overall, we see that most (62%) Hispanic children lived in a household that experienced at least one form of material hardship in the past year; 37 percent were in households that experienced just one hardship, 16 percent experienced two hardships, and 9 percent experienced three or four. Mirroring the patterns seen across the individual hardship domains, there was substantial variation in cumulative hardship across the socio-demographic measures included in this analysis.

- Parent birth within or outside the United States. In 2020, approximately two thirds (66%) of Hispanic children who lived with at least one parent born outside of the United States were in households reporting at least one hardship in the past year, as were 56 percent of Hispanic children with U.S.-born parents. Approximately, 28 percent of Latino children with a non-U.S.-born parent were in households that experienced two (17%) or more (11%) hardships, as were 23 percent of children with U.S.-born parents (16% experienced two and 7% experienced three or four).

- Poverty status. In 2020, most Latino children in households with incomes below (82%) or near the poverty threshold (70%) were in households that experienced at least one of the measured hardships in the past year. Combined, more than 4 in 10 Hispanic children in households with incomes below the poverty threshold were in households that experienced two (25%) or more (18%) hardships, as were one third (22% experienced two and 12% experienced three or four) of those in households with incomes near poverty. Half (50%) of Latinx children in households with income above 200 percent of the FPL experienced at least one hardship, while 14 percent were in households reporting two (10%) or more (4%).

- Family structure. The percentages of Hispanic children in households experiencing one or two hardships in the past year were relatively similar in 2020, regardless of whether these children lived with one or two parents. However, children who lived with one parent were more likely (13%) than those living with two parents (7%) to be in households that have experienced three or four hardships.

Figure 5. Sixty-two percent of Hispanic children, and over 80 percent of those living in households with incomes below the poverty threshold, live in a household that reported experiencing at least one form of material hardship

Percentage of Hispanic children living in a household that reported experiencing at least one form of material hardship at some point in the past year, overall, and by parental birth within or outside of the United States, poverty status, and family structure, 2020.

Summary and Implications

Despite overall declines in levels of child and family poverty25 in the United States over the past several decades, far too many Latinx children continue to live in households that struggle economically. This brief, which has examined the burden of material hardship among Latino children, contributes to the growing body of descriptive research on material hardship by providing updated statistics on material hardship among Hispanic children (as opposed to households or adults) while paying attention to important diversity within the Hispanic population by parent birth within or outside the United States, poverty status, and family structure.

Our analysis shows that, in 2020, most (62%) Hispanic children lived in households that experienced at least one form of the material hardships we measured. Just over one third of Latino children (37%) lived in households that experienced only one of the hardship domains, but a notable percentage experienced co-occurring hardships: 16 percent lived in households that experienced two hardships and almost 1 in 10 (9%) lived in households that experienced three or four hardships.

A wide range of income support policies in the United States26 are designed to support child and family well-being and reduce the material hardships they face. However, these programs may not be accessible to all those in need27 and the process of securing various assistance can be burdensome.28 As we have shown, more than one quarter of Latino children lived in a household with two or more of the measured hardship domains, as did 44 percent of Latinx children whose households had incomes below the federal poverty threshold. Applying and maintaining eligibility for any one program can be challenging, but doing so for more than one program may pose insurmountable barriers for families. While some states offer combined application processes for certain public benefits programs, many families still face significant challenges to both applying for and maintaining eligibility29 across multiple programs. For instance, while applying for benefits might occasionally be streamlined, the process of staying eligible for each program often remains separate and burdensome.28 Efforts to improve coordination and integration of services across policies and programs could enhance the efficiency of these processes, reducing the overall burden on families navigating multiple benefit programs. Additionally, continued and expanded investments in programs that provide families with the flexibility to use income supports as they see fit (including work-conditioned and unconditional cash transfer programs) would also allow families to better address co-occurring hardships across multiple domains.

Medical hardship—having a parent with no health insurance or reporting unpaid medical debt—was the most frequently reported hardship indicator in 2020, with more than 4 in 10 children living in a household that experienced it at some point in the past year. Notably, among those experiencing medical hardship, children with a parent born outside of the United States were most likely to have a parent with no health insurance, while children with U.S.-born parents were most likely to have unpaid medical debt. Even though children typically have greater access to public health insurance than adults,30 high medical bills and uninsured parental care can create financial burdens that may lead to other aspects of material hardship like housing and food security31; these burdens are also associated with poorer health outcomes.32 Increasing access to affordable health insurance options through Medicaid expansion/subsidies33 and community-based programs34 might help address medical affordability and cost burdens for Hispanic families, particularly those in households with low incomes. However, while Medicaid is a valuable resource, it is not available to most non-citizens.35 In addition, policy measures that help control health care costs more broadly may also reduce out-of-pocket expenses.

Though less prevalent than medical hardship, similar proportions of Latinx children—approximately one fifth—lived in households that experienced each of the other hardship domains in 2020, including food insecurity, housing quality hardship, and bill-paying hardship. Hispanic children in households with incomes below or near the poverty threshold and those living with one parent (vs. two) were more likely than other children to live in households that experienced these hardships. Increasing enrollment in and the accessibility of community- and federally funded food assistance programs—like SNAP and WIC—could help Hispanic families alleviate food insecurity; however, such actions must address the unique barriers many Latino families face, including language barriers36 and immigration-related concerns.37 These efforts—complemented with community-level interventions such as food banks and other local food programs—have been found to improve food accessibility.38,39 Similarly, housing and bill-paying hardship may be mitigated by expanding policies that support housing affordability and stability, including rental assistance40 and tenant protections.

Finally, expanding financial literacy and budgeting education programs41—or ensuring that these programs are embedded in other existing programs (e.g., TANF)—could provide families with the skills and knowledge needed to manage their finances effectively, particularly those struggling to pay bills.

Limitations

This analysis measured the prevalence of material hardship in 2020, the year when COVID-19 emerged as a pandemic in the United States. As has been well-documented, the pandemic had wide-ranging impacts on family well-being. As noted above, Latino families experienced some of the largest health42 and socioeconomic impacts43,44 from COVID, which likely increased the prevalence of material hardship experienced by Hispanic families over the course of that year (relative to prior years)—despite the fact that the federal relief efforts implemented that year helped decrease overall rates of material hardship by the end of 2020.45 Although the economy has since recovered—and Hispanic families currently have above average employment rates46—high inflation in 2021 and 2022 led to substantial increases in the cost of living, which continued to put pressure on families’ ability to meet their basic needs.

Additionally, the measures we examined are only a subset of hardships families may face. One pressing—and increasing—hardship for many families is the cost of high-quality and reliable child care. Latinx families already face significant challenges finding affordable child care,47 a struggle further exacerbated by rising child care costs.48 The absence of affordable child care often disrupts the careers of parents or caregivers, which depletes their income-earning potential and hinders their economic mobility.49 Although we did not examine child care hardship in this analysis, we agree with recommendations to more fully integrate child care burden into future measures of economic and material hardship.50 Not considered in this analysis are other sources of financial stress (beyond medical debt) many families face, such as student loans, other credit card debt, and transportation insecurity.51 Finally, it is important to remember that we have assessed material hardships in a one-year period; current experiences of hardship do not necessarily capture past experiences,52 which still matter for the health and well-being of children and their families.

Data, Measures, and Methods

Data and sample

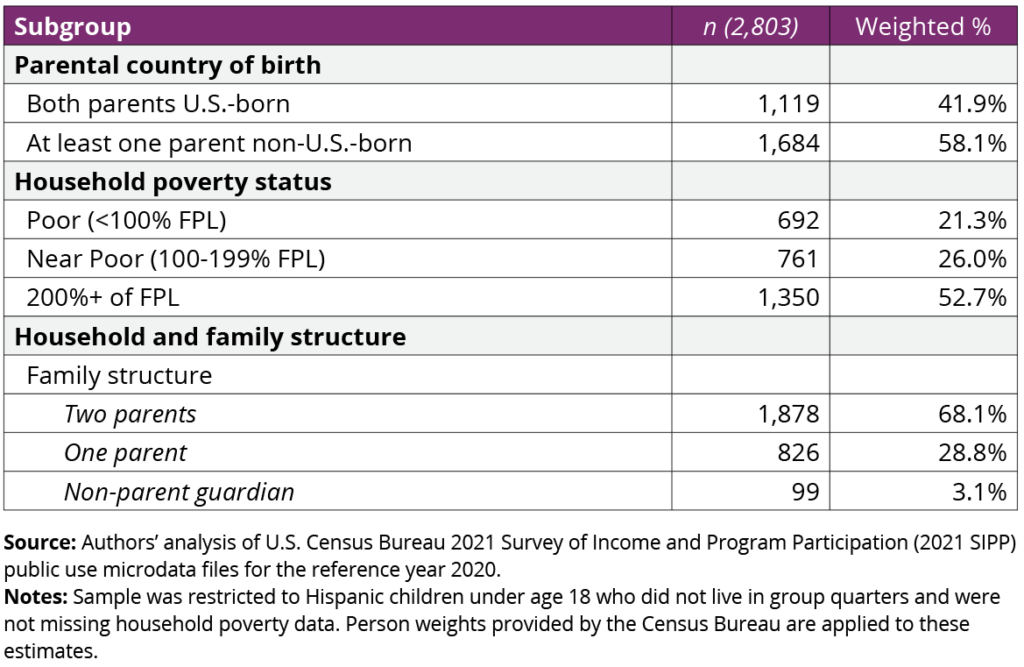

For this analysis, we used data from the 2021 Survey of Income and Program Participation (SIPP), a nationally representative longitudinal survey administered by the U.S. Census Bureau covering the reference period January–December 2020. It provides information on the income, employment, household composition, and government program participation of individuals and households.

Our analytic sample was restricted to children under age 18 identified as Hispanic (n=2,803). Hispanic children who lived in group quarters or other nonpermanent residences and who were missing household income-to-poverty ratio data were excluded from the analytic sample. Consistent with the U.S. Census definition, respondents were included in the Hispanic sample if they responded affirmatively to having Hispanic, Latino, or Spanish origin.

Our analysis resulted in descriptive estimates of the above measures of household material hardship—individually and cumulatively—for the full sample of Hispanic children and separately for Hispanic children by parental country of birth (both parents born in United States vs. at least one parent born outside the United States); household poverty status (<100% of the Federal Poverty Level [FPL; in poverty], 100–199% of the FPL [low income], and 200%+ of FPL); and family structure (two-parent vs. one-parent). A small percentage of children in this sample lived in households with no parent present, so results are not shown for this group. We tested whether the prevalence of household hardship measures among Hispanic children statistically differed (p<.05) by parental birth in or outside the United States, household poverty status, and family structure using chi-square tests. All analyses were completed using Stata/MP version 16.1.

Table A: Percent of Hispanic children experiencing material hardship, overall and by subgroup, 2020

Table B. Socio-demographic characteristics of Hispanic children <18

Footnotes

a We use “Hispanic,” “Latino,” “Latinx,” and “Latine” interchangeably throughout the brief. The terms are used to reflect the U.S. Census definition to include individuals having origins in Mexico, Puerto Rico, and Cuba, as well as other “Hispanic, Latino or Spanish” origins.

b Income-based poverty measures and material hardship measure distinct aspects of economic well-being. As summarized by Iceland and Sakamoto (2019), income-based poverty measures “capture an outcome of instrumental importance—income compared to a needs standard,” while hardship measures “have the advantage of measuring concrete problems households face rather than being a proxy measure of the resources people have to avoid true hardship.” Economic hardship has multifaceted effects on the well-being and functioning of families and children, influencing various aspects of their lives. For this reason, researchers employ poverty measures and measures of material hardship to monitor the economic well-being of families and households. The most used poverty measures—the official poverty measure (OPM) and the supplemental poverty measure (SPM)—use different strategies to measure a family’s access to economic resources. These income-based measures, however, do not always capture the full economic reality of children’s families or whether they have access to the basic resources they need to thrive.

c The poverty threshold for a family of four in 2020 was $24,600.

d The SIPP’s measures of adult well-being are household measures that refer to conditions experienced during a reference year. We preserved the data from December of the reference year and applied calendar year weights to assess the experience of material hardship in 2020, in alignment with the 2021 Survey of Income and Program Participation Users’ Guide. For measures related to housing quality, SIPP questions refer to the residence in which the reference person lived for the majority of the year if they lived in multiple locations within the reference year.

e Two-parent households include parents who are married or cohabitating/unmarried, and children can be biological, adopted, and stepchildren.

f Relatively small percentages of children were in households that reported four hardships.

Suggested citation

Wildsmith, E., Alvira-Hammond, M., McClay, A., & Cedeño, D. (2024). More than 6 in 10 Hispanic children’s households experienced material hardship in 2020. National Research Center on Hispanic Children & Families. DOI: 10.59377/158w4977o

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to thank the Steering Committee of the National Research Center on Hispanic Children & Families—along with Natasha Pilkauskas, Dana Thomson, Yiyu Chen, Kristen Harper, Laura Ramirez, and Ana Maria Pavic—for their helpful comments, edits, and research assistance at multiple stages of this project. The Center’s Steering Committee is made up of the Center investigators—Drs. Natasha Cabrera (University of Maryland, Co-PI), Danielle Crosby (University of North Carolina, Greensboro, Co-PI), Lisa Gennetian (Duke University; Co-PI), Lina Guzman (Child Trends, PI), Julie Mendez (University of North Carolina, Greensboro, Co-PI), and Maria Ramos-Olazagasti (Child Trends, Deputy Director and Building Capacity lead)—and federal project officers Drs. Ann Rivera, Jenessa Malin, and Kimberly Clum (Office of Planning, Research and Evaluation), and Dr. Shirley Huang (Society for Research in Child Development Policy Fellow, Office of Planning, Research and Evaluation).

Editor: Brent Franklin

Designers: Catherine Nichols & Joseph Boven

About the Authors

Elizabeth Wildsmith, PhD, is a research scholar at Child Trends and has worked with the National Research Center on Hispanic Children & Families since 2013. She is a family demographer whose research examines the process of marriage, cohabitation, and childbearing, as well as how social and family contexts may increase exposure to, or offer protection from, risk factors associated with the negative health and well-being of women, children, and families.

Marta Alvira-Hammond, MA, is a research scientist at Child Trends and a former research fellow of the National Research Center on Hispanic Children & Families. She is also a PhD candidate in the Department of Sociology at Bowling Green State University. Ms. Alvira-Hammond’s research interests include immigration and immigrant families, inequality, poverty and self-sufficiency, the safety net, and health.

Alison McClay, MPH, is a research scientist at Child Trends and has worked with the National Research Center on Hispanic Children & Families since 2020. She is passionate about applied, multidisciplinary research that support and promote health equity and adolescent, young adult, and family well-being.

Diana Cedeño, PhD, is a senior researcher at The National Research Center on Hispanic Children and Families. Dr. Cedeño’s research interests include social exclusion and inclusion among low-income Latinx families, community engagement as a source if resilience, and understanding transnational and translingual families.

About the Center

The National Research Center on Hispanic Children & Families (Center) is a hub of research to help programs and policy better serve low-income Hispanics across three priority areas: poverty reduction and economic self-sufficiency, healthy marriage and responsible fatherhood, and early care and education. The Center is led by Child Trends, in partnership with Duke University, University of North Carolina at Greensboro, and University of Maryland, College Park. This publication was made possible by Grant Number 90PH0028 from the Office of Planning, Research and Evaluation, Administration for Children and Families, U.S. Department of Health and Human Services. Its contents are solely the responsibility of the authors and do not necessarily represent the official views of the Office of Planning, Research and Evaluation, the Administration for Children and Families, or the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services.

Copyright 2024 National Research Center on Hispanic Children & Families

References

1 Healthychildren.org. (n.d.). When Things Aren’t Perfect: Caring for Yourself & Your Children. https://www.healthychildren.org/English/healthy-living/emotional-wellness/Building-Resilience/Pages/When-Things-Arent-Perfect-Caring-for-Yourself-Your-Children.aspx

2 Rodems, R., & Shaefer, H. L. (2020). Many of the kids are not alright: Material hardship among children in the United States. Children and Youth Services Review, 112, 104767. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.childyouth.2020.104767

3 Measures of Material Hardship. (n.d.). ASPE. Retrieved January 18, 2023, from https://aspe.hhs.gov/reports/measures-material-hardship

4 Heflin, C., Sandberg, J., & Rafail, P. (2009). The Structure of Material Hardship in U.S. Households: An Examination of the Coherence behind Common Measures of Well-Being. Social Problems, 56(4), 746–764. https://doi.org/10.1525/sp.2009.56.4.746

5 Neckerman, K. M., Garfinkel, I., Teitler, J. O., Waldfogel, J., & Wimer, C. (2016). Beyond Income Poverty: Measuring Disadvantage in Terms of Material Hardship and Health. Academic Pediatrics, 16(3, Supplement), S52–S59. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.acap.2016.01.015

6 Thomas, M.M.C. (2022). Longitudinal Patterns of Material Hardship Among US Families. Soc Indic Res 163, 341–370. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11205-022-02896-8

7 Rodems, R. M. (2018). Hidden Hardship: Three Essays on Material Well-Being and Poverty in the United States. https://deepblue.lib.umich.edu/bitstream/handle/2027.42/145911/rodems_1.pdf

8 Schenck-Fontaine, A., & Ryan, R. M. (2022). Poverty, Material Hardship, and Children’s Outcomes: A Nuanced Understanding of Material Hardship in Childhood. Children, 9(7). https://doi.org/10.3390/children9070981

9 Hill, L., Artiga, S., & Ndugga, N. (2023). COVID-19 Cases, Deaths, and Vaccinations by Race/Ethnicity as of Winter 2022. KFF. https://www.kff.org/coronavirus-covid-19/issue-brief/covid-19-cases-deaths-and-vaccinations-by-race-ethnicity-as-of-winter-2022/#:~:text=Despite%20these%20fluctuations%20in%20patterns,deaths%20compared%20with%20White%20people

10 Gould, E., Perez, D., & Wilson, V. (2020). Latinx workers—particularly women—face devastating job losses in the COVID-19 recession. Economic Policy Institute. https://www.epi.org/publication/latinx-workers-covid/

11 Noe-Bustamante, L., Krogstad, J. M., & Lopez, M. H. (2021). 2. Latinos have experiences widespread financial challenges during the pandemic. Pew Research Center. https://www.pewresearch.org/race-ethnicity/2021/07/15/latinos-have-experienced-widespread-financial-challenges-during-the-pandemic/

12 Kim, L., Logan, D., & Scott, M. E. (2023). Supporting diverse family structures through social safety net programs. Child Trends. DOI: 10.56417/6087g1130v

13 Bureau, U. C. (n.d.). Half of People of Dominican and Salvadoran Origin Experienced Material Hardship in 2020. Census.Gov. Retrieved April 18, 2023, from https://www.census.gov/library/stories/2022/09/hardships-wealth-disparities-across-hispanic-groups.html

14 Iceland, J., & Sakamoto, A. (2022). The Prevalence of Hardship by Race and Ethnicity in the USA, 1992-2019. Population research and policy review, 41(5), 2001–2036. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11113-022-09733-3

15 Rodems, R., & Shaefer, L. H. (2019). Many of the Kids are not Alright: Material Hardship Among Children in the United States. Poverty Solutions, University of Michigan. https://poverty.umich.edu/files/2019/09/PovertySolutions-MaterialHardship-PolicyBrief-final.pdf

16 Tolbert, J., & Drake, P. (2023). Key Facts about the Uninsured Population. KFF. https://www.kff.org/uninsured/issue-brief/key-facts-about-the-uninsured-population/

17 Kalousova, L., & Burgard, S. A. (2013). Debt and Foregone Medical Care. Journal of Health and Social Behavior, 54(2), 204-220. https://doi.org/10.1177/0022146513483772

18 National Academies of Sciences, E., and Medicine. (2023). An Updated Measure of Poverty: (Re)Drawing the Line. The National Academies Press. https://doi.org/10.17226/26825

19 Mendes de Leon, C. F., & Griggs, J. J. (2021). Medical Debt as a Social Determinant of Health. JAMA, 326(3), 228–229. https://doi.org/10.1001/jama.2021.9011

20 Yabroff, K. R., Zhao, J., Han, X., & Zheng, Z. (2019). Prevalence and Correlates of Medical Financial Hardship in the USA. Journal of general internal medicine, 34(8), 1494–1502. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11606-019-05002-w

21 Health Resources and Services Administration, Maternal and Child Health Bureau. (2023). National Survey of Children’s Health, Material Hardship Among Children, 2022. https://mchb.hrsa.gov/sites/default/files/mchb/data-research/nsch-data-brief-2022-material-hardship.pdf

22 Measures of Material Hardship: Final Report. ASPE. Retrieved February 8, 2024, from https://aspe.hhs.gov/reports/measures-material-hardship-final-report

23 Clair, A. Housing: an Under-Explored Influence on Children’s Well-Being and Becoming. Child Ind Res 12, 609–626 (2019). https://doi.org/10.1007/s12187-018-9550-7

24 U.S. Department of Agriculture (USDA). (2023). Measurement. https://www.ers.usda.gov/topics/food-nutrition-assistance/food-security-in-the-u-s/measurement/#:~:text=Food%20insecurity%20is%20the%20limited,foods%20in%20socially%20acceptable%20ways.

25 Thomson, D., Ryberg, R., Harper, K., Fuller, J., Paschall, K., Franklin, J., & Guzman, L. (2022). Lessons From a Historic Decline in Child Poverty. Child Trends. https://doi.org/10.56417/1555c6123k

26 Pilkauskas, N. V. (2023). Child Poverty and Health: The Role of Income Support Policies. The Milbank Quarterly, 101(S1), 379–395. https://doi.org/10.1111/1468-0009.12623

27 Ullrich, R., Schmit S., & Cosse, R. (2019). Inequitable Access to Child Care Subsidies. CLASP. https://www.clasp.org/wp-content/uploads/2022/01/2019_inequitableaccess.pdf

28 Barnes, C. Y. (2021). “It Takes a While to Get Used to”: The Costs of Redeeming Public Benefits. Journal of Public Administration Research and Theory, 31(2), 295-310. https://doi.org/10.1093/jopart/muaa042

29 Gennetian, L. A., Mendez, J., Hill, Z. (2019). How State-level Child Care Development Fund Policies May Shape Access and Utilization among Hispanic Families. National Research Center on Hispanic Children & Families. https://www.hispanicresearchcenter.org/research-resources/how-state-level-child-care-development-fund-policies-may-shape-access-and-utilization-among-hispanic-families/

30 Spencer, D. L., McManus, M., Call, K. T., Turner, J., Harwood, C., White, P., Alarcon, G. (2018). Health Care Coverage and Access Among Children, Adolescents, and Young Adults, 2010–2016: Implications for Future Health Reforms. Journal of Adolescent Health, 62(6), 667-673. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jadohealth.2017.12.012

31 Cha, A. E., & Cohen, R. A. (2020). Problems paying medical bills, 2018. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. NCHS data brief, no. 357. https://stacks.cdc.gov/view/cdc/85027

32 Choi S. (2018). Experiencing Financial Hardship Associated With Medical Bills and Its Effects on Health Care Behavior: A 2-Year Panel Study. Health Education & Behavior, 45(4), 616-624. https://doi.org/10.1177/1090198117739671

33 Lee, H., Porell, F. W. (2020). The Effect of the Affordable Care Act Medicaid Expansion on Disparities in Access to Care and Health Status. Medical Care Research and Review, 77(5), 461-473. doi:10.1177/1077558718808709

34 Williams D. R., Cooper L. A. (2019). Reducing Racial Inequities in Health: Using What We Already Know to Take Action. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 16(4), 606. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph16040606

35 Broder, T., Lessard, G., & Moussavian, A. (2021). Overview of Immigrant Eligibility for Federal Programs. National Immigration Law Center. https://www.nilc.org/wp-content/uploads/2021/08/overview-immeligfedprograms-article.pdf

36 Varela, E. G., McVay, M. A., Shelnutt, K. P., & Mobley, A. R. (2023). The Determinants of Food Insecurity Among Hispanic/Latinx Households With Young Children: A Narrative Review. Advances in Nutrition, 14(1), 190–210. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.advnut.2022.12.001

37 Haley, J. M., Kenney, G. M., Bernstein, H., & Gonzalez, D. (2020). One in Five Adults in Immigrant Families with Children Reported Chilling Effects on Public Benefit Receipt in 2019. Urban Institute. https://www.urban.org/sites/default/files/publication/102406/one-in-five-adults-in-immigrant-families-with-children-reported-chilling-effects-on-public-benefit-receipt-in-2019_0.pdf

38 Hsiao, B.-S., Sibeko, L., Wicks, K., & Troy, L. M. (2018). Mobile produce market influences access to fruits and vegetables in an urban environment. Public Health Nutrition, 21(7), 1332–1344. https://doi.org/10.1017/S1368980017003755

39 Roncarolo, F., Bisset, S., Potvin, L. (2016). Short-Term Effects of Traditional and Alternative Community Interventions to Address Food Insecurity. PLOS ONE. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0150250

40 Fischer, W., Rice, D., & Mazzara, A. (2019). Research Shows Rental Assistance Reduces Hardship and Provides Platform to Expand Opportunity for Low-Income Families. Center on Budget and Policy Priorities. https://www.cbpp.org/sites/default/files/atoms/files/12-5-19hous.pdf

41 Lusardi, A., Hasler, A., & Yakoboski, P. J. (2021). Building up financial literacy and financial resilience. Mind & Society, 20(2), 181–187. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11299-020-00246-0

42 Hill, L., Artiga, S., & Ndugga, N. (2023). COVID-19 Cases, Deaths, and Vaccinations by Race/Ethnicity as of Winter 2022. KFF. https://www.kff.org/coronavirus-covid-19/issue-brief/covid-19-cases-deaths-and-vaccinations-by-race-ethnicity-as-of-winter-2022/#:~:text=Despite%20these%20fluctuations%20in%20patterns,deaths%20compared%20with%20White%20people

43 Gould, E., Perez, D., & Wilson, V. (2020). Latinx workers—particularly women—face devastating job losses in the COVID-19 recession. Economic Policy Institute. https://www.epi.org/publication/latinx-workers-covid/

44 Noe-Bustamante, L., Krogstad, J. M., & Lopez, M. H. (2021). 2. Latinos have experiences widespread financial challenges during the pandemic. Pew Research Center. https://www.pewresearch.org/race-ethnicity/2021/07/15/latinos-have-experienced-widespread-financial-challenges-during-the-pandemic/

45 Karpman, M., & Zuckerman, S. (2021, April 14). Average Decline in Material Hardship during the Pandemic Conceals Unequal Circumstances. Urban Institute. https://www.urban.org/research/publication/average-decline-material-hardship-during-pandemic-conceals-unequal-circumstances

46 Employment Characteristics of Families – 2022. (2023). Bureau of Labor Statistics, U.S. Department of Labor. https://www.bls.gov/news.release/pdf/famee.pdf

47 Crosby, D. A., Mendez, J., & Barnes, A. (2019). Child Care Affordability Is Out of Reach for Many Low-Income Hispanic Households. National Research Center on Hispanic Children & Families. https://www.hispanicresearchcenter.org/research-resources/child-care-affordability-is-out-of-reach-for-many-low-income-hispanic-households/

48 Gould, E., & Cooke, T. (2015). High quality child care is out of reach for working families. Economic Policy Institute. https://www.epi.org/publication/child-care-affordability/

49 Morrissey, T. W. (2017). Child care and parent labor force participation: A review of the research literature. Review of Economics of the Household, 15(1), 1–24. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11150-016-9331-3

50 National Academies of Sciences, E., and Medicine. (2023). An Updated Measure of Poverty: (Re)Drawing the Line. The National Academies Press. https://doi.org/10.17226/26825

51 Murphy, A. K., McDonald-Lopez, K., Pilkauskas, N., & Gould-Werth, A. (2022). Transportation Insecurity in the United States: A Descriptive Portrait. Socius, 8. https://doi.org/10.1177/23780231221121060

52 Campbell, C., O’Brien, G., & Tumin, D. (2022). Timing and Persistence of Material Hardship Among Children in the United States. Maternal and Child Health Journal, 26(7), 1529–1539. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10995-022-03448-9