Sep 17, 2019

Research Publication

An Economic Portrait of Low-Income Hispanic Families: Key Findings from the First Five Years of Studies from the National Research Center on Hispanic Children & Families

Authors:

Most Hispanic children under age 18 (57 percent) lived in poor or near-poor households in 20171—that is, households with income less than 200 percent of the federal poverty level.a,b Growing up in poverty presents risks to children’s development and overall well-being.2,3 Collectively, the findings synthesized here offer a portrait of the economic life of Hispanic families that highlights ways in which the experiences of Hispanic families with low incomes differ from those of their non-Hispanic peers, and point to ways in which policy and programs can help support their economic well-being.

This synthesis covers key findings from the National Research Center on Hispanic Children & Families’ first five years (2013–2018) regarding Hispanic families’ economic well-being, including parents’ employment and the characteristics of their jobs; the prevalence and level of poverty experienced by Hispanic families; the stability (or lack thereof) in household income; families’ use of public assistance programs; and (because work, income, and policy shape family time) parents’ investment of time in their children. To better understand how the experiences of Hispanics might differ from other demographics, many of the findings describe comparisons between Hispanic families and children and their non-Hispanic white and black peers.c When feasible, findings also describe how the economic experiences of Hispanic families varied by whether a parent was born in the United States.d Data for the findings described here were drawn from large, nationally representative data, including the Survey of Income and Program Participation (SIPP), the American Time Use Survey (ATUS), and the American Community Survey (ACS). One goal of the National Research Center on Hispanic Children & Families is to advance the field’s understanding of the socioeconomic context of Hispanic children and families who live in poor or low-income households to inform programs and services designed to support their economic self-sufficiency and socioeconomic mobility.

How common is adult employment in low-income Hispanic families compared to their white and black peers?

Most Hispanic children residing in households with low incomes live with an employed adult. A key distinguishing feature of low-income Hispanic households with children was the presence of an employed adult.4 Parental employment rates were especially high among low-income Latino children who resided with at least one parent who was an immigrant (81 percent of these children resided in a household with at least one employed adult), in 2012.4 In comparison, 64 percent of low-income Latino children living with parents who were both nonimmigrants lived with an employed adult, compared to 67 percent of white and 54 percent of black children.4

What are the employment characteristics of low-income Hispanic parents and how do they differ for those born in the United States versus outside it?

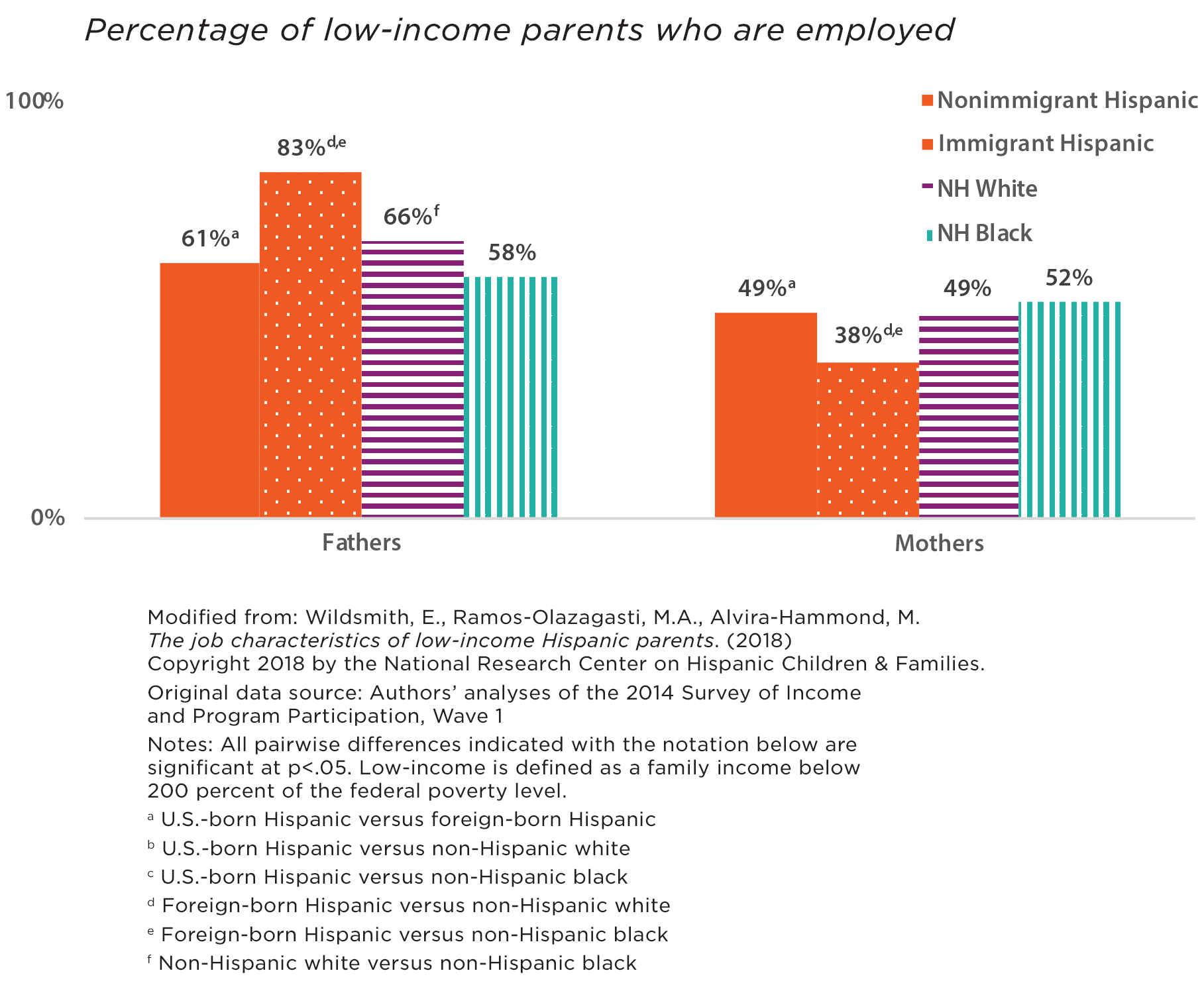

Most low-income Hispanic fathers and many low-income Hispanic mothers are employed, but employment varies by whether these parents were born in the United States. In any given month in 2013, Hispanic fathers who were immigrants and had low incomes were more likely to be employed than their nonimmigrant counterparts (83 vs. 61 percent, respectively).5 In the same year, many low-income Hispanic mothers were employed, but those who were immigrants were less likely to be employed than those who were born in the United States (38 vs. 49 percent, respectively; Figure 1).5

Figure 1. Among low-income fathers, Hispanics born outside of the United States were most likely to be employed

Notably, most immigrant and nonimmigrant Hispanic fathers with low incomes had been stably employed in one job for an average of four to five years.5 Low-income Hispanic mothers who were born outside of the United States had been in their longest-held job for longer (four years) than their nonimmigrant counterparts (three years); up to one third had been at their current job for less than a year.5

About half of Hispanic parents with low-income have jobs with irregular or nonstandard work schedules, with few differences by whether they were born in the United States. In 2013, 56 percent of nonimmigrant Latino fathers with low incomes and 49 percent of low-income Latino immigrant fathers worked a nonstandard or irregular schedule—that is, a schedule that was not a regular Monday to Friday daytime schedule.5 Among mothers with low incomes, 44 percent of those born in the United states and 53 percent of those who were immigrants had an irregular or nonstandard work schedule at their current job.

Despite high rates of employment, access to employer-provided health insurance is lower among low-income Hispanic parents who are immigrants compared to those born in the United States. About one third (35 percent) of Hispanic fathers with low incomes who were born outside of the United States reported having access to health insurance through their employer in 2013, compared to 50 percent of those who were born in the United States.5 Similarly, access to employer-provided health insurance was lower among Hispanic mothers who were born outside of the United States (42 percent) than among their nonimmigrant counterparts (56 percent).

How do Hispanic families’ poverty status, income level, and income stability compare to their non-Hispanic peers?

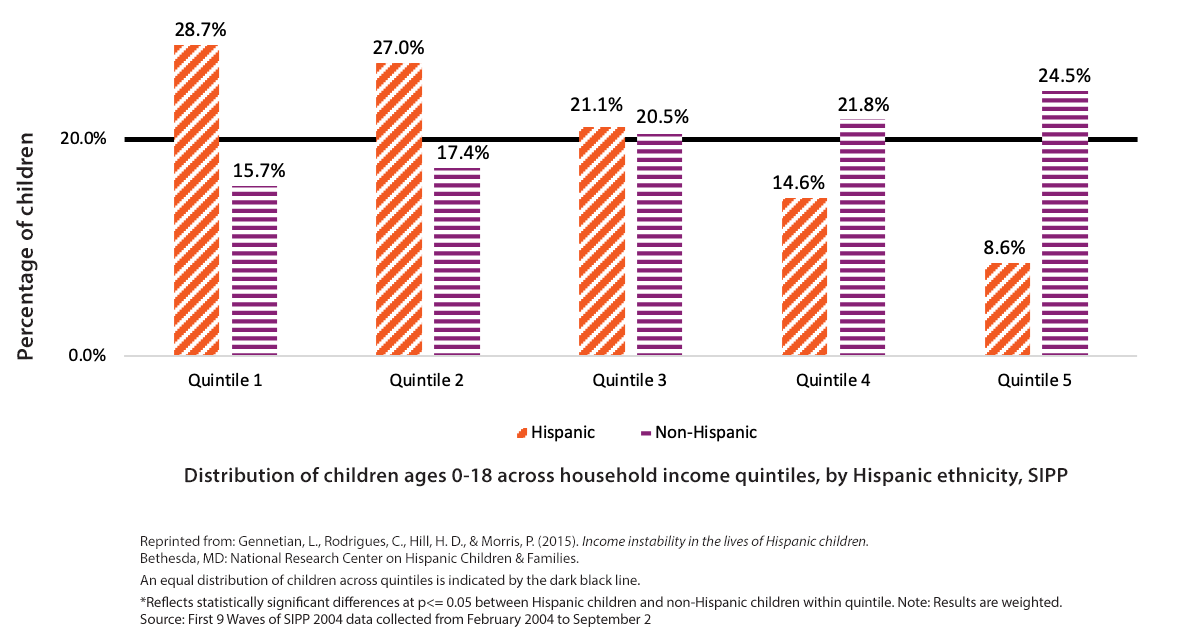

Hispanic children are twice as likely to live in poverty as white children, and many live in deep poverty. Despite the high levels of employment among Hispanic families, approximately 11 million Hispanic children lived in or near poverty in 2014.6 Of those, 2.2 million lived in deep poverty—that is, in households with incomes less than 50 percent of the federal poverty line, or $11,925 for a family of four in 2014.6 When considering the entire income distribution of households with children from birth to age 18 in the United States, from 2004 to 2006, Hispanic children were more likely than their non-Hispanic peers (black, white, and other non-Hispanic children) to live in the lowest-income households (29 vs. 16 percent, respectively) and less likely to live in the highest-income households (Figure 2).7,8

Figure 2. A higher proportion of Hispanics than non-Hispanic children lived in low-income households (2004-2006)

Household income in Hispanic households is low, but more stable than in non-Hispanic households. Hispanic children in the lowest-income households experienced more income stability than their non-Hispanic (i.e., majority black and white) counterparts, and were less likely to experience negative income shocks in the period from 2004 to 2006.7,9 In other words, they were more likely to live in households with incomes that were consistently low, and less likely to experience sudden reductions in household income.7 The co-occurrence of stable and low incomes did not vary by whether there was at least one adult in the household who was born in the United States, or by citizenship status.7

What sources of income contribute to income stability among Hispanic families with the lowest incomes?

The main source of income stability is earnings. Income stability for low-income families typically comes from two sources: 1) earnings from employed adults and 2) monthly receipt of government benefits such as food stamps. In contrast to their non-Hispanic peers, earnings are the primary source of income stability for low-income Hispanic households, rather than receipt of public benefits.7 In fact, other studies document that participation in public assistance programs like the Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program (SNAP), which can alleviate poverty-related hardships, is lower among Latino families with children living in poverty than among their black counterparts.10 Low wages, however, mean that these income-stable Latino households have chronically low incomes, despite their earnings stability.7

Why do many Hispanic parents living in poverty not apply for public assistance?

Parents with low to middle incomes report not using public assistance for a number of reasons, the most common of which is their belief that they do not need any. While these reasons varied among parents with low to middle incomes,e they did not differ by race or ethnicity of the parent.11 The most commonly reported reason for not applying for public assistance among Hispanic, white, and black parents was “don’t need any.”11

However, while low- to middle-income parents report a lack of knowledge about public assistance programs similarly across racial/ethnic groups, Hispanic parents report immigration-related concerns as additional reasons for not using public assistance. Low-income families of all racial/ethnic backgrounds reported a lack of knowledge about the availability of benefits as one of the main reasons for not using them, even among those families who had previously received assistance and those with the lowest earned incomes.11 However, low-income Latino parents were more likely than their white or black peers to report ineligibility due to immigration status as a reason for not applying for aid; this was true even for those who became naturalized citizens.11

How do Hispanic parents with low incomes balance their time with their children, in paid work, and in other activities, and how does this balance compare to their white and black peers?

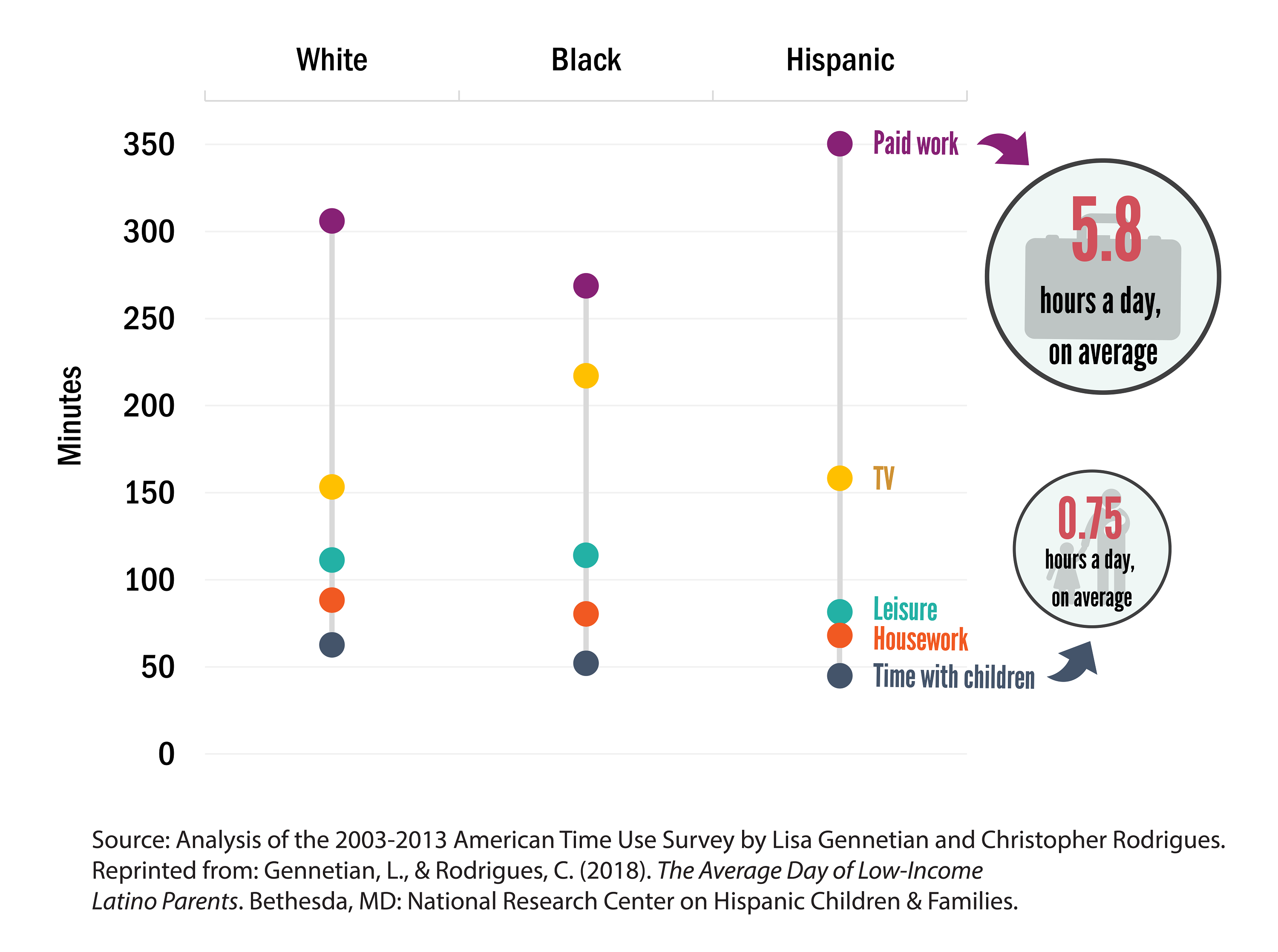

The ways in which low-income residential fathers spend their time varies by race and ethnicity; the opposite is true for low-income mothers. Strong labor force participation among Hispanic fathers may confer economic and other benefits to families but may also come at a cost to family life. From 2003 to 2013, low-income Hispanic fathers residing with their children spent more time on paid work but less time with their children (activities including caring for and helping raise children, education, play, health, and travel) than their white and black peers (Figure 3).12

Figure 3. Low-income Hispanic fathers spent substantially more time on paid work and less time on housework or leisure than low-income white or black fathers

On an average day, low-income Hispanic fathers spent 45 minutes on the aforementioned activities with their children, whereas white fathers spent an average of 62 minutes and black fathers spent an average of 52 minutes. Of the time that Hispanic fathers spent with their children, roughly 33 minutes were spent caring for and helping their children (versus educational activities, play, health, or travel).12 Low-income Hispanic fathers spent substantially more time on paid work and less time on housework or leisure than low-income white or black fathers. Other estimates suggest that an hour spent in paid work among low-income Hispanic fathers reduces time spent with their children by 11 minutes, a tradeoff that is not present among low-income black or white fathers (or mothers).13

Low-income Hispanic mothers spent an average of 105 minutes per day on educational activities, play, health, travel, and caring for and helping their children, similar to the amount of time black and white mothers spent with their children. But Hispanic mothers spent more time on housework and less time on paid work or leisure than their peers.12

Conclusion and Future Directions for Research

The economic characteristics of Hispanic children’s households display both strengths and risks to children’s development. On the one hand, Hispanic children in low-income households tend to reside in households with high employment and stable incomes, which can be a stabilizing force for family routines, reducing parental stress and promoting child well-being.14,15 Still, household income among many Hispanic families is chronically low, and earnings are from jobs with low wages and unreliable or irregular hours16; this can interfere with families’ economic mobility and make it challenging for parents to juggle work with time and energy to invest in their children.

The potential role of anti-poverty policies in supporting Latino families remains unclear, in part because Latino families underutilize public assistance programs that can help mitigate poverty-related hardships.10,17 To that end, the Center’s work examines ways in which state policies and practices might shape Hispanic families’ access to public assistance programs that can increase household resources and support child well-being. For example, in How State-level Child Care Development Fund Policies May Shape Access and Utilization among Hispanic Families, the authors examined ways in which eligibility and documentation requirements vary by state. They also examined state-level variation in how program information is made accessible to parents. Based on their review, the authors identified ways that policies and practices might differentially affect access to Child Care Development Fund (CCDF) subsidies among Hispanic families.18 Similar reviews of Temporary Assistance for Needy Families, Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Programs, and related income supports are underway. And because education is a main pathway toward economic mobility, future research will explore the education trajectories of Hispanic parents, along with variation by mothers and fathers, household income, nativity status, and English language proficiency.

NOTES

a The terms “Hispanic” and “Latino” are used interchangeably in this paper. The Census Bureau gives survey respondents the option of identifying themselves (or their minor children) as having origins in Mexico, Puerto Rico, Cuba, or “another Hispanic, Latino, or Spanish origin.”

b The federal poverty level in 2017 for a family of four was $24,600.

c Comparisons to other racial groups were often not possible due to small sample sizes.

d Hereafter, for simplicity, referred to as immigrant versus nonimmigrant, respectively.

e The majority had incomes below 185 percent of the federal poverty line—a commonly used threshold for federal assistance programs.

Suggested Citation:

Gennetian, L., Guzman, L., Ramos-Olazagasti, M., & Wildsmith, E. (2019). An Economic Portrait of Low-Income Hispanic Families: Key Findings from the First Five Years of Studies from the National Research Center on Hispanic Children & Families. Report 2019-03. Bethesda, MD: National Research Center on Hispanic & Families. Retrieved from: https://hispanicrescen.wpengine.com/research-resources/an-economic-portrait-of-low-income-hispanic-families-key-findings-from-the-first-five-years-of-studies-from-the-national-research-center-on-hispanic-children-families.

References

1 KIDS Count Data Center. (2019). Children Below 200 Percent Poverty by Race in the United States Baltimore, MD: The Annie E. Casey Foundation. Retrieved from https://datacenter.kidscount.org/data/tables/6726-children-below-200-percent-poverty-by-race?loc=1&loct=1#detailed/1/any/false/871,870,573,869,36,868,867,133,38,35/10,11,9,12,1,185,13/13819,13820

2 Bradely, R. H., & Corwyn, R. F. (2002). Socioeconomic Status and Child Development. Annual Review of Sociology, 53(1), 371-399.

3 Duncan, G. J., & Brookes-Gunn, J. (2000). Family Poverty, Welfare Reform, and Child Development. Child Development 71(1), 188-196.

4 Turner, K., Guzman, L., Wildsmith, E., & Scott, M. (2015 ). The Complex and Varied Households of Low-Income Hispanic Children. Bethesda, MD: National Research Center on Hispanic Children and Families. Retrieved from https://hispanicrescen.wpengine.com/research-resources/the-complex-and-varied-households-of-low-income-hispanic-children/

5 Wildsmith, E., Ramos-Olazagasti, M. A., & Alvira-Hammond, M. (2018). The Job Characteristics of Low-Income Hispanic Parents. Bethesda, MD: National Research Center on Hispanic Children & Families. Retrieved from https://hispanicrescen.wpengine.com/publications/the-job-characteristics-of-low-income-hispanic-parents/

6 Wildsmith, E., Alvira-Hammond, M., & Guzman, L. (2016). A National Portrait of Hispanic Children in Need (No. 2016-15). Bethesda, MD: National Research Center on Hispanic Children & Families. Retrieved from https://hispanicrescen.wpengine.com/publications/a-national-portrait-of-hispanic-children-in-need/

7 Gennetian, L., Rodriguez, C., Hill, H. D., & Morris, P. A. (2015). Income Instability in the Lives of Hispanic Children Bethesda, MD: National Research Center on Hispanic Children & Families. Retrieved from https://hispanicrescen.wpengine.com/research-resources/income-instability-in-the-lives-of-hispanic-children/

8 Gennetian, L., Rodriguez, C., Hill, H. D., & Morris, P. A. (2018). Income Level and Volatility by Children’s Race and Hispanic Ethnicity. Journal of Marriage and Family, 81(1), 204-229.

9 Gennetian, L. (2016). Income Instability Data Training Tip Sheet. Bethesda, MD: National Research Center on Hispanic Children & Families. Retrieved from https://hispanicrescen.wpengine.com/research-resources/income-instability-data-training-tip-sheet/

10 Skinner, C. (2011). SNAP Take-Up Among Immigrant Families with Children. New York, NY: National Center for Children in Poverty. Retrieved from http://www.nccp.org/publications/pdf/text_1002.pdf

11 Alvira-Hammond, M., & Gennetian, L. (2015). How Hispanic Parents Perceive their Need and Eligibility for Public Assistance. Bethesda, MD: National Research Center on Hispanic Children & Families. Retrieved from https://hispanicrescen.wpengine.com/publications/how-hispanic-parents-perceive-their-need-and-eligibility-for-public-assistance/

12 Gennetian, L., & Rodriguez, C. (2018). The Average Day of Low-Income Latino Parents. Bethesda, MD: National Research Center on Hispanic Children & Families. Retrieved from https://hispanicrescen.wpengine.com/research-resources/infographic-the-average-day-of-low-income-latino-parents/

13 Gennetian, L. A., & Rodrigues, C. (Forthcoming). Mothers’ and Fathers’ Time Spent with Children in the U.S. Variations by Race/Ethnicity Within Income from 2003 to 2013.

14 Yeung, W., Linver, M., & Brookes-Gunn, J. (2002). How Money Matters for Young Children’s Development: Parental Investment and Family Processes. Child Development, 73(6), 1861-1879.

15 Hill, H. D., Morris, P. A., Gennetian, L., Wolf, S., & Tubbs, C. (2013). The Consequences of Income Instability for Children’s Well-Being. Child Development Perspectives, 7(2), 85-95.

16 Crosby, D., & Mendez, J. (2017). How Common are Nonstandard Work Schedules Among Low-Income Hispanic Parents of Young Children? Bethesda, MD: National Research Center on Hispanic Children & Families. Retrieved from https://hispanicrescen.wpengine.com/research-resources/how-common-are-nonstandard-work-schedules-among-low-income-hispanic-parents-of-young-children/

17 Williams, S. (2013). Public Assistance Participation Among U.S. Children in Poverty, 2010. Bowling Green, OH: National Center for Family & Marriage Research. Retrieved from https://www.bgsu.edu/content/dam/BGSU/college-of-arts-and-sciences/NCFMR/documents/FP/FP-13-02.pdf

18 Gennetian, L., Mendez, J., & Hill, Z. (2019). How state-level Child Care Development Fund Policies May Shape Access and Utilization Among Hispanic Families. Bethesda, MD: National Research Center on Hispanic Children & Families. Retrieved from www.hispanicresearchcenter.org/publications/how-state-level-child-care-development-fund-policies-may-shape-access-and-utilization-among-hispanic-families/

20 Hill, Z., Gennetian, L., & Mendez, J. (2019). A Descriptive Profile of State Child Care and Development Fund Policies in States with High Populations of Low-income Hispanic Children. Early Childhood Research Quarterly, 47, 111–123.

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to thank the Steering Committee of the National Research Center on Hispanic Children & Families, and staff from OPRE, for their feedback on earlier drafts of this synthesis. Additionally, we thank Shelby Hickman for her assistance with earlier drafts of this synthesis and Sara Dean, Isabel Griffith, and Deja Logan for their research assistance support.

Editor: Brent Franklin

Designer: Catherine Nichols