Oct 4, 2023

Research Publication, Research Series

Early Care and Education Providers Vary in Their Availability and Flexibility to Meet Hispanic Families’ Needs

Authors:

Introduction

High-quality early care and education (ECE) services have been shown to promote Latinoa children’s early development1 while providing critical support for parental employment.2 Optimizing these social benefits, however, requires an adequate and accessible supply of ECE providers who serve Hispanic families. Among the factors that shape ECE access are whether providers offer care services that align with families’ needs.3,4 For example, many Hispanic children have parents who work nonstandard, irregular, and/or unpredictable hours, necessitating flexible care options that can accommodate these types of schedules.5

In this brief, we use data from the 2019 National Survey of Early Care of Education (NSECE)6 to describe, on a national level, several aspects of ECE provider availability and flexibility that may influence how accessible these providers are to Latino households, including those with low incomes. We report on the percentages of providers offering full-time, year-round, and nonstandard hours; flexible care schedules and payment options; and enrollment availability across three broad types of child care: center-based programs, listed home-based providers (most of whom are licensed and have no prior relationship with the children in their care), and unlisted home-based providers (commonly referred to as ‘family, friend, and neighbor care’). For each type of care provider, we compared whether indicators of availability and flexibility in high-Hispanic-serving settings, in which Hispanic enrollment is 25 percent or more, differed from those in low-Hispanic-serving settings, where Hispanic enrollment is below 25 percent.b,c,7 We also tested whether provider characteristics in high- and low-Hispanic-serving settings in 2019 differed from those reported for the ECE supply in 2012.8

ABOUT THIS BRIEF

This series draws on nationally representative data from the 2019 National Survey of Early Care and Education (NSECE) to describe multiple aspects of child care access and utilization for children in low-income Latino families, including the availability, flexibility, and affordability of care, as well as the characteristics of settings and providers that serve Hispanic children. These descriptive analyses update similar analyses focused on ECE access for Latino families with young children that drew from the 2012 NSECE. For more information, readers are encouraged to review other reports in the series, as well as our synthesis on child care access for Latino families.

Our analysis of the 2019 NSECE offers two important sets of insights. First, as an update to the national portrait provided in 2012, these data reveal the state of child care supply and services for Latino families seven years later—after a period of additional public investments in ECE and expanded state pre-kindergarten programs9 but also following a marked shift in the sociopolitical environment featuring heightened anti-immigrant sentiment and policy actions.10 Second, the 2019 data document the state of the child care sector leading into the COVID-19 pandemic, which created unprecedented strains on ECE systems and families, especially in Black and Brown communities. Emerging evidence suggests that many parents of young children—primarily mothers, and especially Latina mothers—have had to reduce their employment because of challenges finding care that meets their needs.11,12,13 Indeed, child care closures during the pandemic occurred disproportionately in high-Hispanic-density communities14 and the size of the Latina child care workforce, especially in Hispanic-dense metro areas, has not returned to pre-pandemic levels.15 Thus, the ECE accessibility gaps for Latino families highlighted below in our results (e.g., limited care options during nonstandard hours, enrollment denials because of limited space) have almost certainly worsened in the wake of the pandemic. Future releases of the NSECE data coupled with these 2019 estimates will provide an important assessment of how the accessibility of providers serving Latino families with low incomes has changed and where critical improvements are needed.

Key Findings

Nationally, in 2019, one in four center-based programs and roughly one in five listed and unlisted home-based providers served a high proportion of Hispanic children (25% or more of children enrolled were Hispanic). Comparing features of high- and low-Hispanic-serving providers within each type of care, we found similar levels of schedule availability and enrollment capacity, but lower levels of flexibility among high-Hispanic-serving providers. Profiles of accessibility on these dimensions varied across centers, listed home-based providers, and unlisted home-based providers, suggesting potential areas of unmet child care needs for working Hispanic families.

Availability of full-time, year-round, and nonstandard care hours

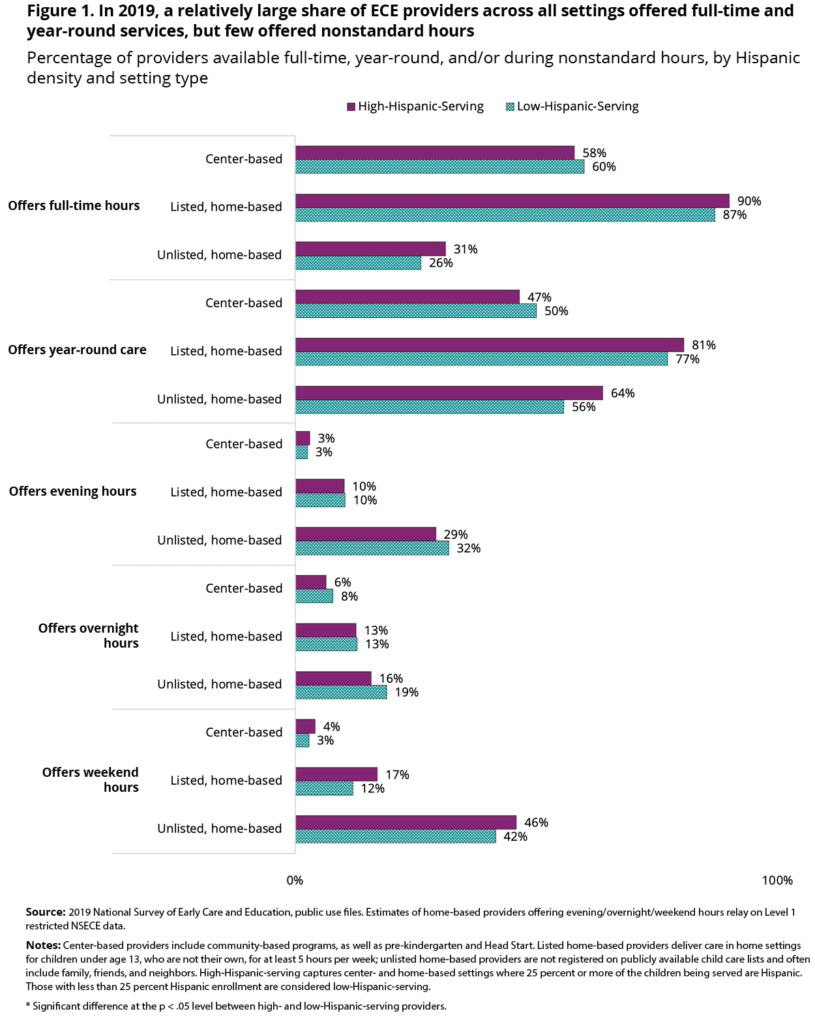

In 2019, provider availability at different times of the day and year was generally similar across high- and low-Hispanic-serving ECE settings but varied by provider type.

- Among centers, roughly half offered full-time hours and/or year-round care; less than 10 percent offered evening, overnight, or weekend hours.

- Among listed home-based providers, most offered full-time hours and year-round care; less than 20 percent offered evening, overnight, or weekend hours.

- Among unlisted home-based providers, approximately 30 percent offered full-time hours, and more than half offered year-round care. Nonstandard hours (and weekend hours in particular) were more common for this type of care, but still offered by fewer than half of providers.

Schedule and payment flexibility for families

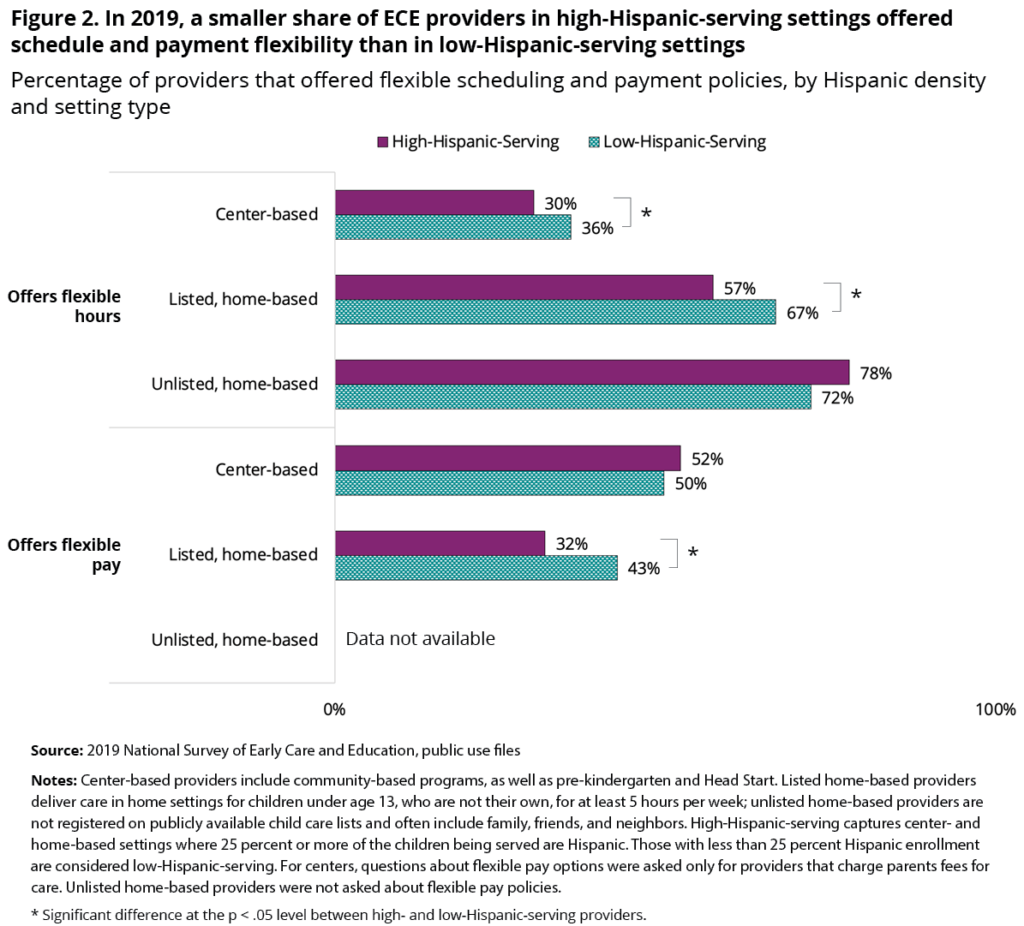

- Roughly one in three centers and two in three listed and unlisted home-based providers offered flexible care schedules, allowing families to vary their hours; this flexibility was generally less prevalent in high-Hispanic-serving settings than in low-Hispanic-serving settings.

- In terms of flexible pay options, approximately half of all centers that charge parents for care allowed them to pay for variable hours instead of a flat tuition fee. Among listed home-based providers, flexible pay options were less likely to be offered in high-Hispanic-serving compared to low-Hispanic-serving settings.

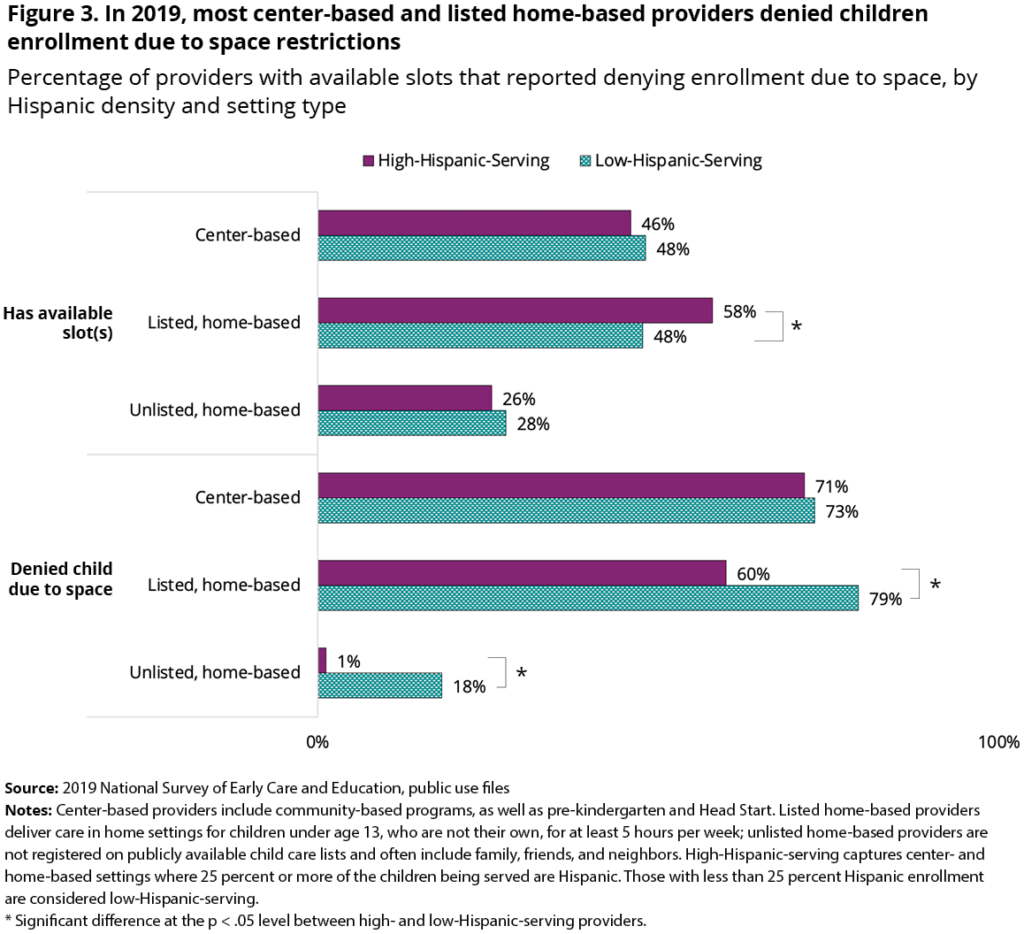

Availability of enrollment slots and children not served

- Across both high- and low-Hispanic-serving settings, most centers and listed home-based providers had denied enrollment in the past year due to space restrictions, although nearly half also reported having at least one open slot at the time of the survey. Among listed home-based providers, high-Hispanic-serving settings were more likely to have open slots than low-Hispanic-serving settings.

- Relatively few unlisted home-based providers reported either open slots or enrollment denials. Those serving a high proportion of Hispanic children were especially unlikely to have denied enrollment.

Comparison of ECE provider supply in 2019 and 2012

Compared to 2012,8 ECE providers across the country in 2019 were more accessible to families on some indicators but less accessible on others.

- A larger share of center-based providers in 2019 offered full-time and year-round hours, while a smaller share of listed and unlisted home-based providers offered nonstandard hours of care.

- In addition, compared to 2012, a smaller share of providers in 2019 offered flexible scheduling and a larger share turned families away because of lack of space, though these differences across time were only significant among low-Hispanic-serving settings.

Findings

Availability of full-time, year-round, and nonstandard care hours

Across high- and low-Hispanic-serving ECE settings, many providers offered full-time and/or year-round services in 2019 (Figure 1). We found that roughly 30 percent of unlisted home-based providers, 60 percent of centers, and 90 percent of listed home-based providers offered full-time care (defined as≥8 hours per day, Monday-Friday). In addition, roughly 50 percent of centers and unlisted home-based providers and more than 75 percent of listed home-based providers offered year-round services. In contrast, across all types of care, few providers offered services during evening, overnight, and weekend hours, especially among center-based programs. Unlisted home-based providers reported the highest levels of nonstandard availability, with roughly 30 percent reporting evening hours and just over 40 percent reporting weekend hours. Within each type of care, the prevalence of nonstandard hours care did not differ significantly between high- and low-Hispanic-serving settings.

Schedule and payment flexibility for families

Roughly one third of center-based programs offered flexible care hours, as did more than half of listed and unlisted home-based providers (Figure 2). Among centers and listed home-based providers, flexible hours were less common in high-Hispanic-serving settings than in low-Hispanic-serving settings. In terms of flexible payment policies that allow parents to pay only for the care hours they use—rather than a flat tuition fee—roughly half of centers that charge parent fees offered this type of flexibility, regardless of Hispanic enrollment density. Notably, 28 percent of centers were not asked about flexible payment policies because they reported being free to families, a feature that clearly addresses affordability barriers. Among listed home-based providers, low-Hispanic-serving settings (43%) were more likely to offer flexible payment options than high-Hispanic-serving settings (32%).

Availability of enrollment slots and children not served

Roughly half of all centers and listed home-based providers (45% to 58%) reported available enrollment slots at the time of the survey, with fewer unlisted home-based providers (25% to 28%) reporting vacancies (Figure 3). Among listed home-based providers, a larger share of high-Hispanic-serving providers had enrollment vacancies, compared to those that were low-Hispanic-serving (58% versus 48%). At the same time, most centers and listed home-based providers (but few unlisted home-based providers) reported denying children enrollment in the past year due to space restrictions. Among both listed and unlisted home-based providers, high-Hispanic-serving providers were less likely to have denied care than their low-Hispanic-serving counterparts.

How do indicators of availability and flexibility among Hispanic-serving ECE providers compare across 2019 and 2012?

The 2012 NSECE study provided the first representative portrait of early care and education providers across the full range of care settings used by families in the United States. 16 Using the same design and similar surveys, the 2019 NSECE offers an updated point-in-time snapshot of the national child care supply just prior to the Covid-19 pandemic. While the cross-sectional design of the NSECE surveys means that individual providers were not tracked over time, comparisons across the two studies offer insight as to how characteristics of the formal and informal child care sector may have shifted from 2012 to 2019. Notably, the NSECE study team reported that the number of individuals providing home-based child care services was roughly 25 percent lower in 2019 than in 2012.17 With these caveats in mind, we compare our 2019 results with similar analyses using the 2012 NSECE data and observe many similarities as well as a few key differences (Table 2).

- In 2019, a significantly larger percentage of high-Hispanic-serving centers offered full-time and year-round services than in 2012. Alternatively, fewer listed and unlisted home-based providers offered evening, overnight, and weekend care hours in 2019 than in 2012.

- In 2019, fewer ECE providers across all care types offered flexible schedule and payment options than in 2012. Among centers, though, the lower rate of flexible schedules in 2019 compared to 2012 was limited to low-Hispanic-serving settings.

- In 2019, a larger share of center-based providers in low-Hispanic-serving settings denied children’s enrollment due to a lack of space than in 2012. In contrast, enrollment denials were reported by a smaller share of unlisted home-based providers in 2019 than in 2012, across both high- and low-Hispanic-serving settings.

Conclusion and Implications

Drawing on national data from the 2019 NSECE, this brief provides a profile of the nation’s ECE supply along indicators of availability, in terms of care offered at a range of times when parents might need it and whether providers have available slots, and flexibility, such that parents are able to use and pay for varying hours of care according to their needs. Given evidence that high-quality ECE can promote positive outcomes for Latino children and families when it is accessible to them,1 we were particularly interested in what these indicators looked like for the one in four center-based programs and one in five listed and unlisted home-based providers in the United States that serve a high proportion (25% or more) of Hispanic children, and how these compared to availability and flexibility of low-Hispanic-serving providers. Our results highlight the need for policies that can improve the fit between ECE programs and the needs of working Hispanic families.

Scheduling challenges for working Hispanic parents trying to access center-based programs

Many Hispanic parents—in particular, those with low incomes—are employed in jobs that include part-time, variable, and nonstandard hours, with short advance notice of work schedules.5,18 ECE providers who offer a wide range of hours and flexible schedules may thus facilitate access for Latino families and support parental employment. However, our findings show that a relatively small share of center-based programs have operating schedules likely to accommodate the needs of working Latino parents, across both high- and low-Hispanic-serving settings. While just over half of centers offered full-time hours (a larger share than in 2012), fewer than half operated year-round and less than 10 percent were open during nonstandard hours. Additionally, most centers, and especially high-Hispanic-serving centers, did not allow for flexible or varying hours of care. Together, these findings may partially reflect that some center-based programs focused on developmental enrichment—especially those that are publicly funded and for preschool-age children (e.g., public pre-K, Head Start)—often operate on a part-time, part-year basis with a set attendance schedule.

In other analyses of the 2019 NSECE data,19 we found that high-Hispanic-serving centers were more likely than those with low Hispanic enrollment to receive public funding, to have teaching staff who are culturally and linguistically representative of the Latino population, and to offer staff coaching and mentoring opportunities shown to support higher-quality classroom interactions. While these features may contribute to higher-quality experiences for children, the current findings on schedule availability suggest that, to access these educational opportunities, working Latino parents are likely to need additional arrangements to cover their child care needs. Potential strategies to increase families’ access to these settings include extended and more flexible service hours and/or seamless wraparound care options, as well as more family-friendly employment policies (e.g., employee-centered scheduling practices) in the low-wage job sector, where Latino parents make up a substantial share of the workforce.

Home-based providers often fill important care gaps, but need additional supports

Our findings on the availability and flexibility of home-based providers serving Latino children aligns with other research highlighting home-based ECE as a critical support to low-income working parents,20 of whom many are Latino.21 Listed home-based providers, which tend to be licensed and operate within the formal child care market, were very likely to report offering full-time and year-round services, although less than 20 percent provided care during nonstandard hours. These providers also offered families a moderate amount of flexibility around schedules and fees, even though a smaller share of high-Hispanic-serving providers offered flexibility compared to their low-Hispanic-serving counterparts. Inconsistent or unpredictable income is likely to be financially challenging for providers running a home-based child care business and may limit their ability to offer flexibility without outside support or subsidization. Data suggest that this segment of the ECE workforce was shrinking prior to the pandemic and has sustained additional losses since 2020.17

Although unlisted home-based providers—also referred to as family, friend, and neighbor (FFN) care—are not part of the formal ECE market and not subject to the same policy levers as centers and listed/licensed home-based providers, we included them in this descriptive profile to capture the full range of care accessed by families and because of their potential importance in filling care gaps not met by other providers. Indeed, our findings showed that, in 2019, a larger share of FFN providers across both high- and low-Hispanic-serving settings provided care during nonstandard hours and offered families flexible scheduling relative to centers and listed home-based providers. These results join other work showing that parents may choose FFN providers not only because of familiarity and possible cultural/linguistic congruence, but also because they tend to be more available, flexible, and affordable than other options.22 We find that FFN providers serving a high proportion of Hispanic children are especially likely to identify as Latino and Spanish-speaking, but are also less likely than low-Hispanic-serving FFN providers to have an ECE degree, field experience, or engagement in professional development. Given their significant role in caring for Latino children and supporting parents’ work, policy efforts should seek additional ways to support this sector of ECE providers. For example, expanding FFN providers’ eligibility to receive CCDF subsidies and/or including them in professional development opportunities and initiatives may improve the quality and stability of care they are able to provide. Networks seeking to advocate for and organize home-based providers have emerged at the local, state, and national levels and may serve as an important liaison in these efforts to the extent that they are meaningfully embedded in Hispanic communities.

Signs of constrained supply and unmet care needs leading into the global pandemic

Finally, our analyses also offer insights about whether high-Hispanic-serving providers have the capacity to serve the number of children who need ECE services. Even when providers can offer care hours and scheduling policies that match families’ needs, these settings will be inaccessible if they do not have vacancies to enroll children. Notably, in 2019, most centers and listed home-based providers across both high- and low-Hispanic-serving settings reported turning families away in the year prior to the survey because of limited capacity. This echoes other work indicating that the ECE supply in many communities is inadequate to meet demand and that Hispanic families are more likely than other racial/ethnic groups to live in “child care deserts” characterized by an insufficient number of licensed providers relative to the number of young children.23 At the same time, roughly half of centers and listed home-based providers in our sample also reported having at least one vacancy at the time of the survey. Taken together, these relatively high rates of denials and vacancies in formal ECE settings may reflect substantial enrollment turnover and/or indicate that providers struggle to meet demand for some types of care (e.g., infant and toddler slots, children with disabilities, or children exhibiting challenging behaviors). Unlisted home-based providers were less likely than other providers to report open slots and very few—especially among high-Hispanic-serving providers—had turned away a family due to lack of space. These results may be unsurprising given these providers’ tendency to care for children from their immediate community or among their network of family and friends.

The capacity of ECE providers to meet families’ care scheduling needs is only one aspect of a complex set of factors that impact ECE access, underscoring the challenging trade-offs that Hispanic families may face in securing and maintaining child care—especially in the context of low incomes and systemic inequities linked to race, ethnicity, and immigration status. Further research is needed to explore how ECE provider schedules covary with other aspects of care (e.g., ages served, quality, services offered, and affordability) and how Hispanic families navigate potential tradeoffs. For example, centers that operate full-time and year-round tend to serve a wider age range of children (infants through school-age) than publicly funded programs for preschool-aged children but may be less affordable given that they are primarily funded through parent fees. Additional research is also needed to identify supports and resources that can help both center- and home-based providers deliver high-quality ECE services to children across various types of care schedules (e.g., evening care or care that accommodates highly variable employment hours), and to identify innovative ways of helping families more seamlessly and sustainably coordinate care across multiple providers. Other reports in this series draw on complementary NSECE provider and household data to provide a more complete picture of ECE access for Latino families as the ECE landscape continues to change emerging from the global Covid-19 pandemic.d Recent estimates suggest the pandemic exacerbated existing child care supply gaps, especially in predominantly Black and Hispanic communities.24 Given disproportionate consequences of the pandemic for Latino families, caregivers/teachers, and communities,15 data-informed strategies for building and sustaining equitable access to high-quality ECE services will be critical going forward.

Data and Methods

The data for this analysis come from the 2019 National Survey of Early Care and Education (NSECE), a set of four interrelated, nationally representative surveys of 1) households with children under age 13, 2) center-based ECE programs, 3) the center-based provider workforce, and 4) home-based providers. This analysis draws specifically on public use data from the center- and home-based surveys to describe the characteristics of center-based providers (includes community-based programs, as well as pre-kindergarten and Head Start). Additionally, public use data and Level 1 restricted data are used to examine the characteristics of listed, home-based providers (those who regularly care for children in home settings that appear on publicly available child care lists as meeting state regulations) and unlisted home-based providers (who provide care for children under age 13, who are not their own, on a regular basis for at least five hours per week; unlisted home providers are not registered on publicly available child care lists and often include family, friends, and neighbors).

The analytic sample for this brief includes 5,465 center-based, 3,294 listed home-based, and 990 unlisted home-based providers serving children from birth to age 5, and for which information was available on the proportion of Hispanic children served (see Table 1). Notably, a significant share of the center-based (20%) and listed home-based workforce (21%) could not be included in the current analysis because of missing data on the key variable of percent Hispanic child enrollment. In most of these cases, providers reported serving at least one Hispanic child but did not provide a specific number and could therefore not be classified as high- or low-Hispanic-serving. Analyses comparing providers with and without percent Hispanic enrollment data available suggested a few differences between these two groups on the characteristics reported in this brief. Notably, center-based providers with missing Hispanic enrollment data were less likely to offer overnight hours and offer flexible schedules and more likely to deny enrollment due to a lack of available space. Additionally, home-based providers with missing Hispanic enrollment data were less likely to have denied enrollment due to a lack of available space and more likely to be open during full-time hours and have a vacant enrollment slot. This is a limitation of our study, as the results reported here may have overestimated or underestimated the prevalence of these features relative to the broader population of ECE providers.

Descriptive analyses on select characteristics of child care providers (see definitions below) were conducted by provider type and the proportion of Hispanic children enrolled. Mean differences across high- and low-Hispanic-serving providers were tested within type of care; significant differences at the p=.05 level are reported in the tables and text. Due to the number of comparisons performed within each type of care, we also used Benjamini-Hochberg adjusted p-values to assess whether significant findings were due to chance.25 This correction did not substantially alter the key findings. Given that the 2012 and 2019 NSECE studies are cross-sectional, our statistical comparisons of estimates across the two time points suggest how characteristics of the overall ECE supply may have shifted during this period but do not reflect changes for individual providers. All analyses were conducted in STATA and were weighted to be nationally representative of center- and home-based providers.26 The sampling frames and weights for listed and unlisted home-based providers vary substantially, so these two groups were analyzed separately.

Definitions

High-Hispanic-serving captures center- and home-based settings where 25 percent or more of the children being served are Hispanic.

Low-Hispanic-serving captures center- and home-based settings where Hispanic children make up less than 25 percent of enrollment.

Year-round care offered captures whether a provider remains open 50 or more weeks per year.

Full-time hours offered indicates whether a provider operates for eight or more hours per day from Monday through Friday, based on providers’ report of their program’s start and end times for up to three different slots per day.

Evening hours offered indicates whether a provider offers care between 7:00pm and 11:00pm.

Overnight hours offered indicate whether a provider offers care between 11:00pm and 6:00am.

Weekend hours offered indicates whether a provider offers care services on weekend days (Saturday and/or Sunday) at any time.

Flexible schedules or hours offered captures whether the provider permits parents to use child care services on a schedule that varies from week to week.

Flexible pay options offered captures whether the provider permits parents to pay for a varying number of child care hours each week. Center-based providers that do not charge parent fees were not asked this question and were coded as missing. Unlisted home-based centers did not respond to this item.

Provider has at least one vacancy captures whether the provider had any open child care enrollment slots at the time of the survey. Center providers reported on the proportion of vacancies in the classroom and home-based providers reported on the number of vacancies for the program. Center- and home-based providers who reported not having an enrollment cap were coded as having at least one vacancy.

Recent enrollment denial due to space indicates whether the provider denied care for a child due to a lack of space (i.e., an available slot) in the 12 months prior to the survey. Center- and home-based providers who indicated that they have placed children on a waiting list were coded as having denied enrollment due to a lack of space.

Table 1. High- and Low-Hispanic-Serving ECE Providers, by Type of Care

Source: National Survey of Early Care and Education 2019, public use files

Notes: This analysis included center-based, listed home-based, and unlisted home-based providers serving children from birth to age 5 with valid information on the number of enrolled Hispanic children; 21% of centers (n = 1,452), 24% of listed home-based providers (1,071), and 15% of unlisted home-based providers (n = 176) were excluded from this report’s analysis, primarily because of missing data on number of Hispanic children enrolled.

Table 2. ECE Provider Characteristics, by Provider Type and Percentage of Hispanic Children Served

Source: 2019 and 2012 National Survey of Early Care and Education, public use files

Notes: Center-based providers include community-based programs, as well as pre-kindergarten and Head Start. Listed home-based providers deliver care in home settings for children under age 13, who are not their own, for at least 5 hours per week; unlisted home-based providers are not registered on publicly available child care lists and often include family, friends, and neighbors. High-Hispanic-serving captures center- and home-based settings where 25 percent or more of the children being served are Hispanic. Those with less than 25 percent Hispanic enrollment are considered low-Hispanic-serving.

1 Analysis relied on Level 1 Restricted NSECE 2019 data.

2 Data are reported only among settings that do charge parents a fee for care and do not incorporate providers that are free of charge to families.

3 Information on the availability of flexible pay among unlisted home-based settings was not available in the public use files as of December 2022 and was not included in these analyses.

4Information about whether center-based providers have at least one vacancy was not available in the 2012 NSECE.

* Significant difference at the p < .05 level between high- and low-Hispanic-serving providers.

a indicates significant difference at the p < .05 level between high-Hispanic-serving settings in 2019 vs. 2012, where the estimate was higher in 2019.

b indicates significant difference at the p < .05 level between high-Hispanic-serving settings in 2019 vs. 2012, where the estimate was higher in 2012.

c indicates significant difference at the p < .05 level between low-Hispanic-serving settings in 2019 vs. 2012, where the estimate was higher in 2019.

d indicates significant difference at the p < .05 level between low-Hispanic-serving settings in 2019 vs. 2012, where the estimate was higher in 2012.

Footnotes

a We use “Hispanic” and “Latino” interchangeably throughout this report. These terms reflect the U.S. Census definition and include individuals having origins in Mexico, Puerto Rico, and Cuba, as well as other “Hispanic, Latino or Spanish” origins.

b We use 25 percent as the cutoff for defining “high-Hispanic-serving” because approximately 25 percent of children in the United States are Hispanic and a higher cutoff would exclude providers in lower-Hispanic-density communities.

c Although we do not make statistical comparisons across centers, listed home-based providers, and unlisted home-based providers, we describe how the pattern of findings varies by provider type.

d To assess the impact of the pandemic on the ECE landscape, the NSECE fielded a COVID-19 supplemental follow-up survey in 2020 and 2021 with center- and home-based providers included in the original 2019 NSECE sample.

Suggested Citation

Stephens, C., Crosby, D., & Mendez, J. (2023). Early Care and Education Providers Vary in Their Availability and Flexibility to Meet Hispanic Families’ Needs. National Research Center on Hispanic Children & Families. https://doi.org/10.59377/658l3776v

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to thank the Steering Committee of the National Research Center on Hispanic Children & Families—along with Katherine Paschall, Kristen Harper, and Laura Ramirez—for their helpful comments, edits, and research assistance at multiple stages of this project. The Center’s Steering Committee is made up of the Center investigators—Drs. Natasha Cabrera (University of Maryland, Co-I), Danielle Crosby (University of North Carolina at Greensboro, Co-I), Lisa Gennetian (Duke University; Co-I), Lina Guzman (Child Trends and PI), Julie Mendez (University of North Carolina at Greensboro, Co-I), and Maria Ramos-Olazagasti (Child Trends and Building Capacity lead)—and federal project officers Drs. Ann Rivera, Jenessa Malin, and Mina Addo (Office of Planning, Research and Evaluation).

Editor: Brent Franklin

Designer: Catherine Nichols

About the Authors

Christina Stephens, PhD, was a predoctoral fellow of the National Research Center on Hispanic Children & Families, in the research area on early care and education. She is now a postdoctoral research associate at the University of Virginia with the Education Science Training Program on English Learners (EL-VEST). Her research focuses on understanding the factors and policies that promote child care access and quality, particularly among low-income families with young children.

Danielle Crosby, PhD, is a co-investigator of the National Research Center on Hispanic Children & Families, co-leading the research area on early care and education. She is an associate professor in the Department of Human Development and Family Studies at the University of North Carolina at Greensboro. Her research focuses on understanding how policies and systems shape early education access and quality for young children in low-income families.

Julia Mendez, PhD, is a co-investigator of the National Research Center on Hispanic Children & Families, co-leading the research area on early care and education. She is a professor in the Department of Psychology at the University of North Carolina at Greensboro. Her research focuses on risk and resilience among ethnically diverse children and families, with an emphasis on parent-child interactions and family engagement in early care and education programs.

About the Center

The National Research Center on Hispanic Children & Families (Center) is a hub of research to help programs and policy better serve low-income Hispanics across three priority areas: poverty reduction and economic self-sufficiency, healthy marriage and responsible fatherhood, and early care and education. The Center is led by Child Trends, in partnership with Duke University, University of North Carolina at Greensboro, and University of Maryland, College Park. The Center is supported by grant #90PH0028 from the Office of Planning, Research, and Evaluation within the Administration for Children and Families in the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services.

The National Research Center on Hispanic Children & Families is solely responsible for the contents of this brief, which do not necessarily represent the official views of the Office of Planning, Research, and Evaluation, the Administration for Children and Families, or the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services.

Copyright 2023 National Research Center on Hispanic Children & Families

References

1 Mendez Smith, J., Crosby, D., & Stephens, C. (2021). Equitable access to high-quality early care and education: opportunities to better serve young Hispanic children and their families. In L. Gennetian & M. Tienda (Eds.): Investing in Latino Youth. Annals of the American Academy of Political and Social Science (AAPSS), 696(1), 80–105. Sage. https://doi.org/10.1177/00027162211041942

2 Mendez, J., Crosby, D., & Siskind, D. (2020). Work Hours, Family Composition, and Employment Predict Use of Child Care for Low-Income Latino Infants and Toddlers. National Research Center on Hispanic Children and Families. https://www.hispanicresearchcenter.org/research-resources/work-hours-family-composition-and-employment-predict-use-of-child-care-for-low-income-latino-infants-and-toddlers/

3 Mendez, J., & Crosby, D. (2018). Why and How Do Low-income Hispanic Families Search for Early Care and Education (ECE)? National Research Center on Hispanic Children and Families. https://www.hispanicresearchcenter.org/research-resources/why-and-how-do-low-income-hispanic-families-search-for-early-care-and-education-ece/

4 Sandstrom, H. & Chaudry, A. (2012). ‘You have to choose your childcare to fit your work’: Childcare decision-making among low-income working families. Journal of Children and Poverty, 2, 89-119. https://doi.org/10.1080/10796126.2012.710480

5 Crosby, D., & Mendez, J. (2017). How Common Are Nonstandard Work Schedules Among Low-Income Hispanic Parents of Young Children? National Research Center on Hispanic Children and Families. https://www.hispanicresearchcenter.org/research-resources/how-common-are-nonstandard-work-schedules-among-low-income-hispanic-parents-of-young-children/

6 NSECE Project Team (National Opinion Research Center). (2021). National Survey of Early Care and Education (NSECE), [United States], 2019. Inter-university Consortium for Political and Social Research [distributor]. https://doi.org/10.3886/ICPSR37941.v3

7 Chen, Y., & Guzman, L. (2021). Latino Children Represent Over a Quarter of the Child Population Nationwide and Make Up at Least 40 Percent in 5 Southwestern States. National Research Center on Hispanic Children and Families. https://www.hispanicresearchcenter.org/research-resources/latino-children-represent-over-a-quarter-of-the-child-population-nationwide-and-make-up-at-least-40-percent-in-5-southwestern-states/

8 Guzman, L., Hickman, S., Turner, K., & Gennetian, L. (2017). How well are early care and education providers who serve Hispanic children doing on access and availability? National Research Center on Hispanic Children and Families. https://www.hispanicresearchcenter.org/research-resources/how-well-are-early-care-and-education-providers-who-serve-hispanic-children-doing-on-access-and-availability/

9 U.S. Department of the Treasury (2021). The Economics of Child Care Supply in the United States. https://home.treasury.gov/system/files/136/The-Economics-of-Childcare-Supply-09-14-final.pdf

10 Rabin, J., Stough, C., Dutt, A., & Jacquez, F. (2022) Anti-immigration policies of the Trump administration: A review of Latinx mental health and resilience in the face of structural violence. Analyses of Social Issues and Public Policy, 22, 876– 905. https://doi.org/10.1111/asap.12328

11 RAPID-EC Project Team. (2022). Forced Out of Work: The Pandemic’s Persistent Effects on Women and Work. https://rapidsurveyproject.com/our-research/forced-out-of-work-pandemics-effect-on-women-and-work

12 Ranji, U., Frederiksen, B., Salganicoff, A., & Long, M. (2021). Women, Work, and Family During COVID-19: Findings from the KFF Women’s Health Survey. KFF. https://www.kff.org/womens-health-policy/issue-brief/women-work-and-family-during-covid-19-findings-from-the-kff-womens-health-survey/

13 Chen, Y. (2023). Latino households with children continued to experience pandemic-related disruptions to their child care arrangements. National Research Center on Hispanic Children & Families. https://www.hispanicresearchcenter.org/research-resources/latino-households-with-children-continued-to-experience-pandemic-related-disruptions-to-their-child-care-arrangements

14 Lee, E. K., & Parolin, Z. (2021). The Care Burden during COVID-19: A National Database of Child Care Closures in the United States. Socius, 7. https://doi.org/10.1177/23780231211032028

15 Laurito, A., & Guzman, L. (2023). Top Latino metro areas saw large declines in child care employment early in the pandemic, with slow recovery among Latino child care workers. National Research Center on Hispanic Children & Families. https://doi.org/10.59377/618h9115q

16 NSECE Project Team (National Opinion Research Center). (2022). National Survey of Early Care and Education (NSECE), [United States], 2012. Inter-university Consortium for Political and Social Research [distributor]. https://doi.org/10.3886/ICPSR35519.v15

17 Datta, A.R., Milesi, C., Srivastava, S., Zapata-Gietl, C. (2021). NSECE Chartbook – Home-based Early Care and Education Providers in 2012 and 2019: Counts and Characteristics. OPRE Report #2021-85. Office of Planning, Research and Evaluation, Administration for Children and Families, U.S. Department of Health and Human Services. https://www.acf.hhs.gov/opre/report/home-based-early-care-and-education-providers-2012-and-2019-counts-and-characteristics

18 Wildsmith, E., Ramos-Olazagasti, M.A., & Avira-Hammond, M. (2018). The Job Characteristics of Low-Income Hispanic Parents. National Research Center on Hispanic Children and Families. https://www.hispanicresearchcenter.org/research-resources/the-job-characteristics-of-low-income-hispanic-parents/

19 Crosby, D., Mendez, J., & Stephens, C. (2023). Characteristics of the early childhood workforce serving Latino children. National Research Center on Hispanic Children & Families. https://www.hispanicresearchcenter.org/research-resources/characteristics-of-the-early-childhood-workforce-serving-latino-children

20 Tonyan, H.A., Paulsell, D., & Shivers, E.A. (2017). Understanding and incorporating home-based child care Into early education and development systems. Early Education and Development, 28(6), 633-639. https://doi.org/10.1080/10409289.2017.1324243

21 Wildsmith, E., Ramos-Olazagasti, M.A., & Alvira-Hammond, M. (2018). The Job Characteristics of Low-Income Hispanic Parents. National Research Center on Hispanic Children & Families. https://hispanicrescen.wpengine.com/publications/the-job-characteristics-of-low-income-hispanic-parents/

22 Administration for Children and Families, Office of Child Care (n.d.) Informal In-Home Child Care. ChildCare.gov. https://childcare.gov/consumer-education/informal-in-home-child-care

23 Malik, R., Hamm, K., Adamu, M., & Morrissey, T. (2018). Child care deserts: An analysis of child care centers by ZIP code in 8 states. Washington, DC: Center for American Progress. https://www.americanprogress.org/issues/early-childhood/reports/2016/10/27/225703/child-care-deserts/

24 Child care Aware of America. (2022). Demanding Change: Repairing our Child Care System. Child Care Aware of America. https://info.childcareaware.org/hubfs/2022-03-FallReport-FINAL%20(1).pdf?utm_campaign=Budget%20Reconciliation%20Fall%202021&utm_source=website&utm_content=22_demandingchange_pdf_update332022

25 Benjamini, Y., & Hochberg, Y. (1995). Controlling the False Discovery Rate: A Practical and Powerful Approach to Multiple Testing. Journal of the Royal Statistical Society. Series B (Methodological), 57(1), 289–300. http://www.jstor.org/stable/2346101

26 National Survey of Early Care and Education Project Team. (2021). 2019 National Survey of Early Care and Education (NSECE) User’s Guide – Center-based Provider. OPRE Report #2021. Washington, DC: Office of Planning, Research, and Evaluation, Administration for Children and Families, U.S. Department of Health and Human Services.