Mar 28, 2024

Research Publication

Google Trends Data May Offer Insights Into Families’ Child Care Needs

Authors:

Researchers, policymakers, and communities need real-time data to identify emerging issues and trends; these data, in turn, can inform policy decisions and programmatic responses. Digital trace data, including sources such as Google Trends (see box), hold significant promise in providing researchers, practitioners, and policymakers with free, accessible, and timely insights on children and families’ needs, preferences, and behaviors. In this brief, we explore the potential for Google Trends data to provide information regarding families’ child care needs during the COVID-19 pandemic.

Access to child care during the COVID-19 pandemic was a significant challenge for parents of preschool-age children, including Latinoa parents.1 In fact, the pandemic’s onset dramatically exacerbated many existing challenges that families already faced in accessing affordable, flexible child care.2 These challenges were especially pronounced among Latino and Black families in households with low incomes.3 Many child care providers closed—especially in Latino communities—while costs increased for child care providers that stayed open.4 Many facilities had limited enrollment and faced repeated COVID-related quarantines.

What is Google Trends?

Google Trends is a publicly available tool that provides the relative search frequency of Google web searches. Specifically, it shows how frequently a term is searched relativeb to the total search volume in a given period of time and within a given geographical space. Search results can be specified by geography (both state and national) and time period.

Additionally, the COVID-19 pandemic made collecting timely survey data more difficult because of the need for social distancing and the rapidly changing response to the pandemic.5 To address some of these gaps in data collection, many researchers turned to digital sources of data—including Google Trends—to access real-time data that did not require in-person participation to collect.6 This method of data collection is increasingly relevant given that, in 2021, more than 93 percent of U.S. adults (and 95% of Hispanic adults) reported using the internet regularly, and more than 77 percent of U.S. adults have broadband internet access at home.7 Researchers in a wide variety of fields—including economics, market research, epidemiology, and public health research—have relied on Google Trends data as a free, widely available, and near-real-time source of information on search patterns as a proxy for interest and behavior.5 In fact, previous research during the COVID-19 pandemic found a close relationship between Google Trends data on child care search and child care supply (as measured by job postings).8

This brief reports on findings from a pilot study that explored the potential for Google Trends to provide insights into child care needs during the COVID-19 pandemic, from 2019 to 2022. Specifically, the study aimed to assess the feasibility of using this data source to (1) explore trends in parents’ search for child care at the national and state levels, in both English and Spanish; and (2) explore search interest relative to the Latino population. These data may serve as a proxy for child care need that can help researchers formulate hypotheses and identify patterns for future inquiry. The data might also help anticipate child care demand, which can inform future investments in child care.

Key Findings

Our findings suggest that Google Trends is a promising source for historical, geographically specific search information that can be useful to contextualize and visualize trends across place and time.

We found that Google Trends provides the ability to:

- Track trends in search terms over time and identify seasonal patterns. Each year, from March 2019 to March 2022, searches for child care peaked in mid-August and dipped around the winter holiday season.

- Track trends of search terms in different languages. As expected, searches using English terms were more common than those using Spanish.

- Capture the volume of searches by state. The highest volume of searches for child care in English language searches was concentrated in the Upper Midwest (especially North Dakota, Minnesota, Iowa, and Nebraska), Washington, DC, and Mississippi.

We also found that combining quantitative data from Google Trends with qualitative data from focus groups allowed unique insights into child care needs and search behaviors. However, we also found that one limitation of Google Trends data is the lack of available demographic data. Future research on the use of Google Trends data should seek to further identify how to study search patterns in specific populations.

Approach

Identifying relevant terms for child care searches

Because we were particularly interested in exploring the potential for Google Trends data to provide insights into Hispanic families’ child care needs, we first conducted four focus groups of two to four Hispanic parents to identify potential terms that Hispanic parents might use to search for child care. Participants were recruited through flyers distributed by Hispanic-led community-based organizations and through religious and educational institutions serving Latino populations in Sacramento, California. Focus groups were conducted in English or Spanish, as preferred by participants. In describing how they searched for child care, many parents reported using internet searches alongside word-of-mouth and recommendations from family. By asking parents to help identify what terms they would use to search for child care, these focus groups helped us compile key search terms in English (daycare, child care, childcare, child care center, childcare center, nursery,c preschool) and Spanish (guardería, cuidado de niños, cuidado infantil, jardín de niños). Most participants in the focus groups reported using search terms in both Spanish and English, including those who primarily spoke Spanish. Many Spanish-speaking participants reported translating search terms into English to try to improve the results of their searches.

Gathering Google Trends data

Using the search terms identified in the focus groups, we next collected quantitative data from Google Trends on relative search frequency of all suggested search terms from March 2019 to March 2022. Google makes this information on relative search frequency available publicly through the Google Trends website (https://trends.google.com/trends). For this project, we collected data on the weekly search frequency of all terms, both nationally and at the state level through the Google Trends website.

We considered all spelling variations (including the presence or absence of accent marks), pluralization, and capitalization9 when entering search terms. Figure 1 shows how the user interface can be used to gather comparative search frequency data.

Figure 1: Google Trends Shows Comparative Interest in Search Terms over Time

Volume of searches for “daycare” and “childcare,” as tracked by Google Trends, March 2019 to March 2022

Source: Google Trends (https://www.google.com/trends).

Google Trends does not provide any demographic data about households making these searches, which precluded us from examining searches in Latino households specifically. We included Spanish-language search terms because it is most likely that searches in Spanish within the United States originate from Latino households.

Google Trends provides relative numbers on a scale from 0 to 100. The values are in relation to the most popular term’s peak search frequency. For example, in English-language data collected for this project, the search term “daycare” was the most searched term. Within the time range selected for data collection, “daycare” searches peaked the week of August 11, 2019. Thus, the relative interest values for all other search terms are in relation to searches for “daycare” recorded during this week. A relative interest value of 50 indicates that the term had half the search volume on that date compared to the peak search date for “daycare.” The relative interest values for Spanish terms are also in relation to the peak in searches for the term “daycare.”

Google Trends also makes search data available with geographical disaggregation, as long as there is sufficient data to protect users’ privacy. Using the “Explore” feature in the Google Trends interface, we downloaded data on search volume at the state level for all terms during this time period.

In addition, to provide demographic context to the geographic Google Trends data, we downloaded estimates of total population and Hispanic population at the state level from the U.S. Census Bureau’s American Community Survey.10 States were categorized as low Hispanic population if the proportion of Hispanic residents was below the median for all US states. States were categorized as high Hispanic population if they were above the median.

Findings

Searches of English-language child care terms over time

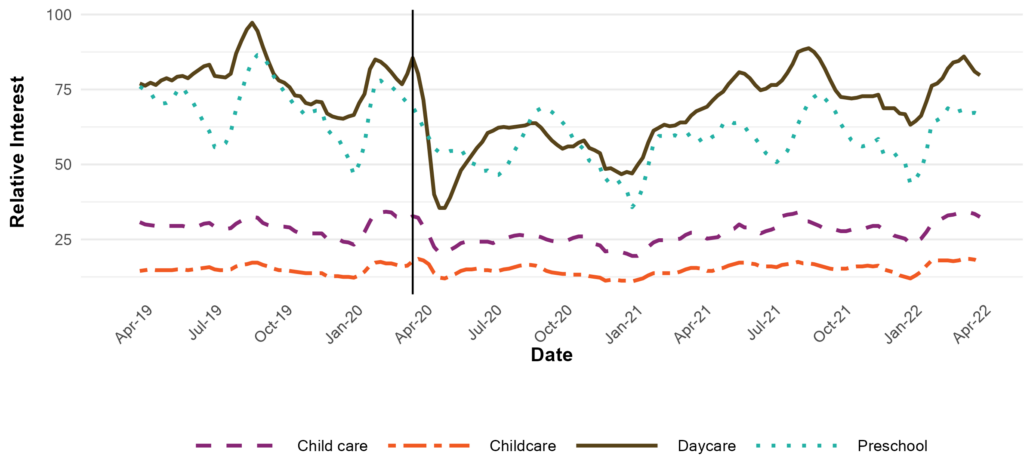

Figure 2 shows English-language searches of child care terms from March 2019 to March 2022. “Daycare” was the most-used English-language term, peaking on the week of August 11, 2019 (and thus serves as the reference comparison for Google Trends estimates shown in this graph). There was a dramatic dip in searches immediately following the start of the COVID-19 pandemic in March 2020 (marked by the vertical line in the graph). On the week of April 12, 2020, we see that the search for “daycare” hit its lowest point, with a relative interest of 32. That is, “daycare” had less than one third the search volume on that date compared to its peak on August 11, 2019. In addition, the data show seasonal patterns, including dips during the winter holiday season and increases around August.

Figure 2. English-language child care searches decreased dramatically following the start of the COVID-19 pandemic

Relative interest in English-language child care search terms, March 2019 to March 2022

Source: Authors’ analyses of Google Trends data (https://www.google.com/trends) from March 2019-March 2022.

The data also show interesting differences in search patterns depending on the specific search term. For example, in Figure 2, we see some differences in patterns of searches for “daycare” and “preschool.” Searches for daycare declined more sharply in the immediate wake of the pandemic relative to searches for preschool, but also rebounded more quickly. These search terms are likely used to seek somewhat different forms of care (i.e., preschool serves older children and may reflect a greater focus on educational experiences, compared to daycare), which may drive some of these patterns. Determining what these differences mean would require additional data collection (including primary data from interviews or surveys to investigate the motivations of individuals in choosing particular terms for searchers, as well as data to validate the relationship of these patterns to labor market participation, stay-at-home orders or other relevant behavioral data). However, these patterns point to new lines of inquiry that would allow a deeper understanding of families’ motivations and needs in searching for child care.

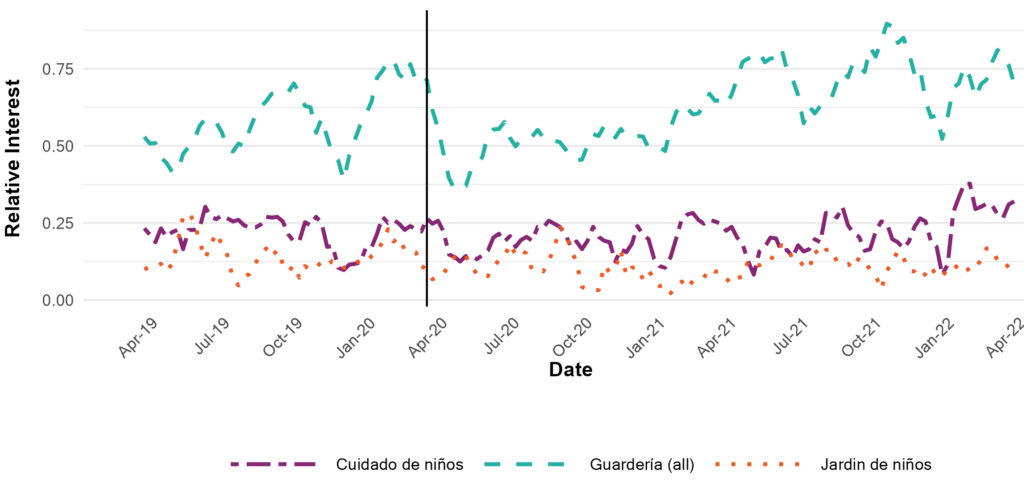

Searches of Spanish-language child care terms over time

Figure 3 depicts relative interest in Spanish-language search terms. For child care searches in Spanish, there was a similar dip across search terms immediately following the start of the COVID-19 pandemic. For “guardería,” there was a slight increase in searches over time following this dip. Notably, the relative interest in Spanish-language searches (relative to the peak in searches for “daycare”) was substantially lower than interest in English-language search terms. (The relative interest in Spanish-language terms peaked at 0.8 on the 0-100 scale.) One limitation of Google Trends is that it does not allow users to select which term to use to set the scale; rather, it calculates relative interests based on the most frequently searched term in the data set. In cases for which some terms are searched substantially more often than others—for example, where English-language searches are hugely more common, or where one term is used far more frequently than other terms of interest—this can make the scale more difficult to interpret.

Figure 3. Spanish-language searches decreased following the start of the COVID-19 pandemic

Relative interest in Spanish-language child care search terms, March 2019 to March 2022

Source: Authors’ analyses of Google Trends data (https://www.google.com/trends) from March 2019-March 2022.

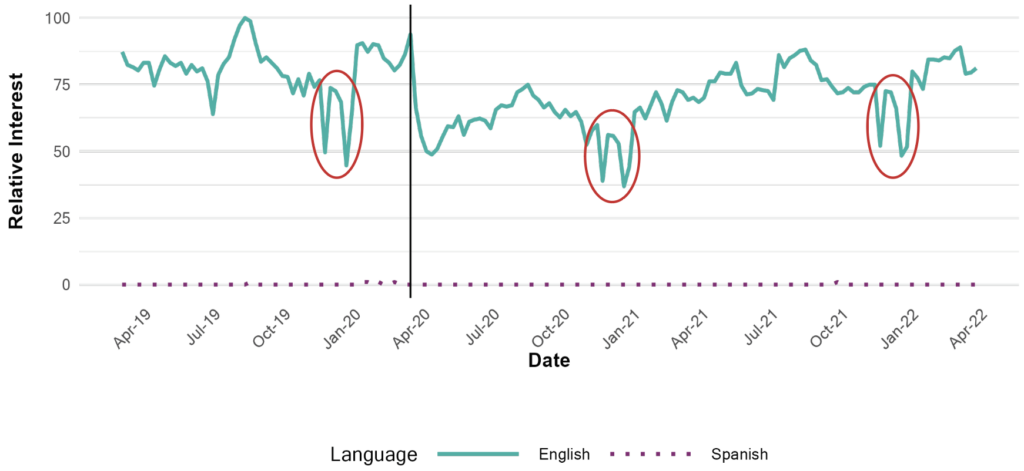

Comparison of English- and Spanish-language child care searches

Figure 4 shows the relative interest in English-language searches compared to Spanish-language searches. Overall, the Spanish-language search volume was substantially lower than searches for terms in English. Information shared during the focus groups suggests that Spanish speakers may use English to search after Spanish-language searches do not return sufficient results. For the English search terms, we observed clear seasonality in searches, with yearly dips near Thanksgiving and Christmas (circled in red).

Figure 4. English-language search volume was much higher than Spanish-language search volume and showed clear seasonal patterns

Comparative search volume in English and Spanish searches for child care (all terms), March 2019 to March 2022

Source: Authors’ analyses of Google Trends data (https://www.google.com/trends) from March 2019-March 2022.

Variation in child care searches by geographic area

Figures 5 through 7 below show search patterns for the period from March 2020 to December 2020. Because Google Trends limits download of geographic comparison data to a single time period, we chose to focus on March 2020 to December 2020 to capture the experience of families as they were adjusting to the COVID-19 pandemic. Figure 5 shows that the highest volume of English-language searches was concentrated in the Upper Midwest (especially North Dakota, Minnesota, Iowa, and Nebraska), Washington, DC, and Mississippi. Figure 5 shows the relative frequency of English language searches for child care in each state and in Washington, DC, reported in relation to the state with the highest search volume (Washington, DC in this case).

Figure 5. During the pandemic, relative interest in child care was highest in the Upper Midwest and lowest in the Southwest

English search volume by state, March to December 2020

Source: Authors’ analyses of Google Trends data (https://www.google.com/trends) from March 2020-March 2020.

Note: Numbers indicate relative search volume, proportionate to state with highest number of searches- (i.e. the state with the value of 100.). For example, a state annotated with 50 would indicate a relative search volume that is 1/2 that of the state with the highest relative search volume.

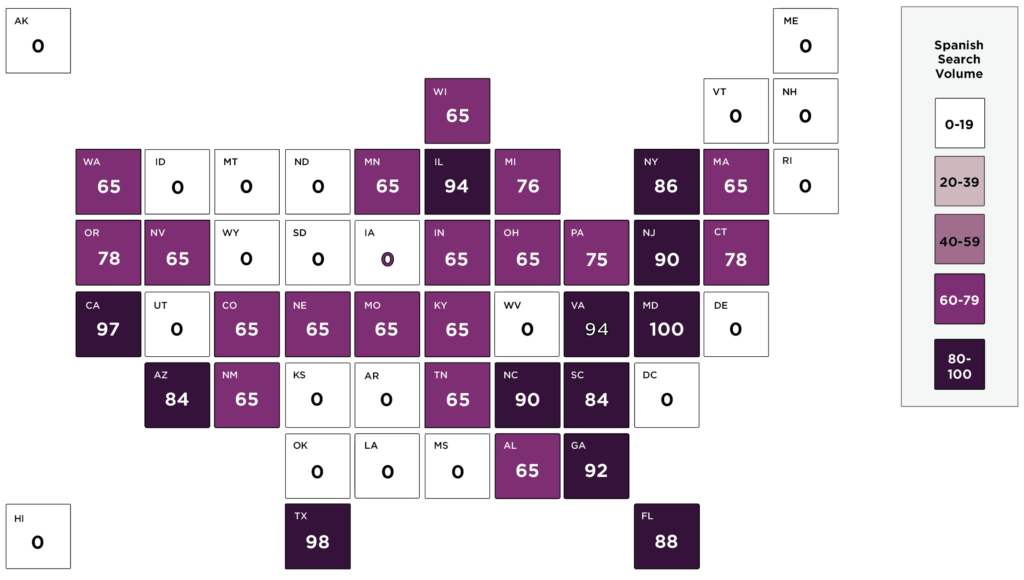

In contrast, in Figure 6, we see that the states with the highest rate of child care searches in Spanish included California, Texas, Illinois, New York, New Jersey, and much of the South Atlantic (especially Virginia, Maryland, North Carolina, South Carolina, Georgia, and Florida). Figure 6 shows the relative frequency of Spanish language searches for child care in each state and in Washington, DC, reported in relation to the state with the highest search volume (Maryland).

Figure 6. Spanish-language relative interest in child care was highest in California, Texas, and the South Atlantic

Spanish search volume by state, March to December 2020

Source: Authors’ analyses of Google Trends data (https://www.google.com/trends) from March-December 2020.

Note: Numbers indicate relative search volume, proportionate to state with highest number of searches- (i.e. the state with the value of 100.). For example, a state annotated with 50 would indicate a relative search volume that is 1/2 that of the state with the highest relative search volume.

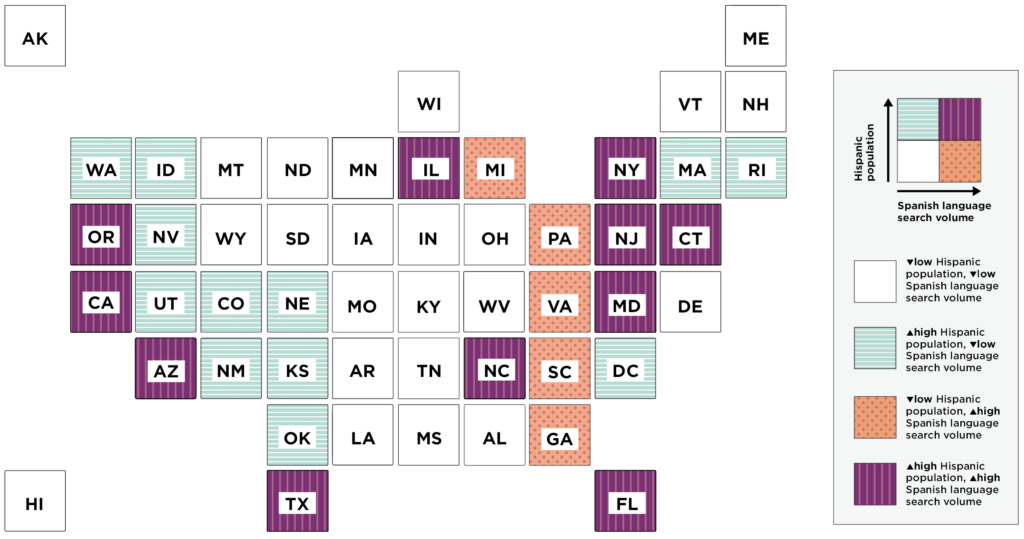

To account for geographic variation in the Hispanic population, we next considered the relationship between Hispanic population and search term volume by comparing Google Trend search volume with the percent of the population who self-identified as Hispanic in each state on the 2020 Census. Figure 7 shows that many states (including Michigan and Atlantic Seaboard states like Pennsylvania, Virginia, South Carolina, and Georgia) had a high Spanish-language search volume despite having relatively lower Hispanic populations . While this exploratory study does not provide insight into why these trends exist, it suggests that further research should explore whether this trend is related to higher child care demand among Latinx populations in these states. This could be investigated through either qualitative data collection or via quantitative survey data.

Figure 7. States in the Atlantic Seaboard had high Spanish-language search interest compared to the proportion of their population that identifies as Hispanic

Spanish-language search volume and Hispanic population, March to December 2020

Source: Authors’ analyses of Google Trends data (https://www.google.com/trends) from March -December 2020.

Conclusions

This pilot study suggests that Google Trends shows promise as a useful tool for exploring trends in searches for child care. Google Trends provides geographically and temporally detailed data that can be used to generate hypotheses and inform future work.

To generate actionable insight from this data, further work is needed to tie search data to parental preferences, parents’ labor force participation, child care availability, or other external measures of behavior and preferences. Future research might explore the association of state child care policies with search volume, or the utility of search data as a leading indicator to forecast parental needs. All of these approaches would be strengthened by using Google Trends data in conjunction with alternative sources.

More broadly, this study suggests that Google Trends offers a promising source of information that could contribute to further research, with several advantages including the opportunity for more real-time insights and lower-cost data collection relative to traditional data sources. Google Trends may prove particularly useful for quick and low-cost development of data drive hypotheses, which could be tested by more extensive primary data collections.

However, this project also highlighted some limitations of Google Trends data—most notably, the inability to obtain demographic information. In this study, we used Spanish-language searches as a proxy for what Latine families specifically may have searched, but this is not sufficient for researchers hoping to draw conclusions for any demographic group or explore variation within demographic groups. This inexact proxy is further complicated by our finding that parents may switch from Spanish to English searches when they do not find the results they were looking for using Spanish search terms. Future research should include more extensive qualitative explorations of how respondents use search as a tool, and how these patterns of searching may tie to families’ preferences and behaviors.

Caveats

This study was not designed to make causal or evaluative claims, but to show how Google Trends may be a promising tool to help researchers and policymakers develop hypotheses and identify patterns for further inquiry. Search behavior is not a primary outcome of interest to researchers, but it does serve as one way to approximate users’ needs and behaviors. While previous research has suggested close links between child care searches and employment-based measures of child care demand,7 further research is needed to completely understand the relationship between Google searches and other child care-related behaviors. Future research could also explore, in more detail, how parents’ search behavior is driven by their needs and preferences.

One added complication is the use of Spanish-language searches as a way to understand the experiences of Latino households. We found in this study that many Latino parents searched in both English and Spanish, which complicates any empirical comparison of English and Spanish searches. Some English-language searches probably come from Hispanic households. We can, however, reasonably confidently assume that most Spanish-language searches originate from Latinx households. This suggests that further research on Spanish-language search trends might be the most promising way to understand Hispanic families’ behaviors.

Footnotes

a We use “Hispanic,” “Latino,” “Latinx,” and “Latine” interchangeably throughout the brief. The terms are used to reflect the U.S. Census definition to include individuals having origins in Mexico, Puerto Rico, and Cuba, as well as other “Hispanic, Latino or Spanish” origins.

b Data on search frequency is relative to the search frequency for the most searched term included in the analysis. Thus, search frequencies can only be compared across terms within a single study and not across projects.

c This term was removed after our review of search data, as “nursery” is thought to be associated with plants and “cuidado” is believed to be associated with the act of being careful—rather than either term being used to search predominantly for child care.

Suggested citation

Kelley, C., Kelley, S., Ferreira van Leer, K., & Balén, Z. (2024). Google Trends data may offer insights into families’ child care needs. National Research Center on Hispanic Children & Families. DOI:10.59377/851a2414c

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to thank the focus group participants and the Steering Committee of the National Research Center on Hispanic Children & Families—along with Todd Grindal, María Ramos-Olazagasti, Valerie Martinez, Laura Ramirez, and Ana Maria Pavić—for their helpful comments, edits, and research assistance at multiple stages of this project. The Center’s Steering Committee is made up of the Center investigators—Drs. Natasha Cabrera (University of Maryland, Co-PI), Danielle Crosby (University of North Carolina at Greensboro, Co-PI), Lisa Gennetian (Duke University; Co-PI), Lina Guzman (Child Trends, PI), Julie Mendez (University of North Carolina at Greensboro, Co-PI), and María Ramos-Olazagasti (Child Trends, Deputy Director and Building Capacity lead)—and federal project officers Drs. Ann Rivera, Jenessa Malin, and Kimberly Clum (Office of Planning, Research and Evaluation), and Dr. Shirley Huang (Society for Research in Child Development Policy Fellow, Office of Planning, Research and Evaluation).

Editor: Brent Franklin

Designers: Catherine Nichols and Joseph Boven

About the Authors

Claire Kelley is a senior data scientist at Child Trends whose work focuses on the intersection of data science and social science research. She is particularly interested in how machine learning, natural language processing, and artificial intelligence enable us to solve problems in health, juvenile justice, and education research.

Sarah Kelley is a senior data scientist at Child Trends, where she applies natural language processing, computer vision, and machine learning technique to answer questions related to social science questions. Her most recent work focuses on using algorithmic explainability techniques to make the use of risk scoring algorithms in juvenile justice systems more equitable.

Kevin Ferreira van Leer, PhD, was a 2019 research scholar with the National Research Center on Hispanic Children & Families, supporting research on early care and education. He is an assistant professor in the Human Development and Family Sciences department at the University of Connecticut. His research examines the social and cultural contexts that promote positive development and liberation for immigrants and their families, with an emphasis on how contexts influence the educational and caregiving experiences of Latine immigrant families.

Zabryna Balén is a research analyst at Child Trends whose work centers on sexual and reproductive health, family formation, and early parenthood, with a particular focus on LGBTQ+ populations. Her work integrates quantitative analysis with data visualization to evaluate programs and share public health data in attempts to create more equitable spaces for adolescents, birthing people, and families.

About the Center

The National Research Center on Hispanic Children & Families (Center) is a hub of research to help programs and policymakers better serve low-income Hispanic families and children across three priority areas: poverty reduction and economic self-sufficiency; early care and education; and parenting, fatherhood, and family life. The Center is led by Child Trends, in partnership with Duke University, University of North Carolina at Greensboro, and University of Maryland, College Park. This publication was made possible by Grant Number 90PH0028 from the Office of Planning, Research and Evaluation, Administration for Children and Families, U.S. Department of Health and Human Services. Its contents are solely the responsibility of the authors and do not necessarily represent the official views of the Office of Planning, Research and Evaluation, the Administration for Children and Families, or the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services.

Copyright 2024 by the National Research Center on Hispanic Children & Families.

References

1Shrimali, B. P. (2020). Child care, COVID-19, and our economic future. Federal Reserve Bank of San Francisco. Retrieved July 10, 2022. https://www.frbsf.org/wp-content/uploads/sites/3/child-care-covid19-and-our-economic-future.pdf

2Stephens, C., Crosby, D., & Mendez, J. (2023). Early Care and Education Providers Vary in Their Availability and Flexibility to Meet Hispanic Families’ Needs. National Research Center on Hispanic Children & Families. https://doi.org/10.59377/658l3776v

3Child care Aware of America. (2022). Demanding Change: Repairing our Child Care System. Child Care Aware of America. https://info.childcareaware.org/hubfs/2022-03-FallReport-FINAL%20(1).pdf?utm_campaign=Budget%20Reconciliation%20Fall%202021&utm_source=website&utm_content=22_demandingchange_pdf_update332022

4Burwick, A., Davis, E., Karoly, L. A., Schulte, T., & Tout, K. (2021). Promoting Sustainability of Child Care Programs during the COVID-19 Pandemic. Child Trends. https://www.childtrends.org/publications/promoting-sustainability-of-child-care-programs-during-the-covid-19-pandemic

5Hensen, B., Mackworth-Young, C. R. S., Simwinga, M., Abdelmagid, N., Banda, J., Mavodza, C., Doyle, A. M., Bonell, C., & Weiss, H. A. (2021). Remote data collection for public health research in a COVID-19 era: ethical implications, challenges and opportunities. Health policy and planning, 36(3), 360-368. https://doi.org/10.1093/heapol/czaa158

6Mangono, T., Smittenaar, P., Caplan, Y., Huang, V. S., Sutermaster, S., Kemp, H., & Sgaier, S. K. (2021). Information-seeking patterns during the COVID-19 pandemic across the United States: Longitudinal analysis of Google Trends data. Journal of Medical Internet Research, 23(5), e22933. https://doi.org/10.2196/22933

7Pew Research Center. (2021). Internet/Broadband Fact Sheet. https://www.pewresearch.org/internet/fact-sheet/internet-broadband/

8Ali, U., Herbst, C. M., & Makridis, C. A. (2021). The impact of COVID-19 on the U.S. child care market: Evidence from stay-at-home orders. Econ Educ Rev, 82, 102094. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.econedurev.2021.102094

9Mavragani A., & Ochoa G. (2019). Google Trends in Infodemiology and Infoveillance: Methodology Framework. JMIR Public Health and Surveillance, 5(2), e13439. https://doi.org/10.2196/13439

10United States Census Bureau (2019). B03002 HISPANIC OR LATINO ORIGIN BY RACE – United States – 2019 American Community Survey 1-Year Estimates. July 1, 2019. Retrieved December 2023.