Jan 17, 2023

Research Publication

Healthy Marriage and Relationship Education Programs May Best Support Outcomes by Addressing Hispanic Families’ Diverse Stressors

Authors:

Overview

Healthy Marriage and Relationship Education (HMRE) programming—also called marriage and relationship education or relationship education programming—is designed to teach participants (which may include youth, individuals, and unmarried, married, or co-parenting couples) how to communicate effectively, manage conflict, identify signs of an unhealthy relationship, and other skills important for developing and maintaining healthy relationships. Federal HMRE programming, in place since 2002, is tailored to people in families with lower incomes to help promote relationship quality, stability, and family well-being.1

A review of the research evaluating the effectiveness of HMRE programming reveals that programming often has positive, albeit modest, impacts on participants’ relationship attitudes, beliefs, and knowledge, and on their commitment and confidence in their relationship.2 Research also shows that HMRE programs often have limited or no effect on other long-term outcomes such as relationship stability, parenting, and family economic outcomes.2 Some of this same research indicates that many program participants face additional life stressors—such as poverty, unemployment, and psychological distress—that may interfere with healthy couple relationships and family functioning.3 To help address some of these additional stressors or needs, which are often beyond the scope of relationship education programming, federally funded HMRE programs have increasingly engaged external partners or referral networks. However, more attention needs to be paid to the role these life stressors play in the lives of program participants and to the dynamics within relationships.1

In this brief, we use data on a sample of Hispanica couples who participated in a large scale, federally funded HMRE evaluation (the Supporting Healthy Marriage [SHM] evaluation) to show the prevalence of some of the key economic, demographic, and personal stressors that research identifies as predictive of relationship quality.4 We first review some of our key findings and summarize some implications of these findings for research and practice. Second, we describe our analysis data, sample, and methods. Third, we describe, in detail, the characteristics of our sample, and the demographic, socioeconomic, and personal stressors they report in their relationships. Finally, we discuss the broader implications of our work and acknowledge some of its limitations.

Key Findings and Implications Overview

Key Findings

- In this sample of Hispanic couples eligible for federally funded HMRE programming, more than a quarter had at least one partner who reported that he or she was unhappy with their marriage and almost 3 in 4 had at least one partner who had thought their marriage was in trouble in the past year.

- Foreign-born couples reported lower rates of marital distress across both measures than U.S.-born or mixed nativity couples.

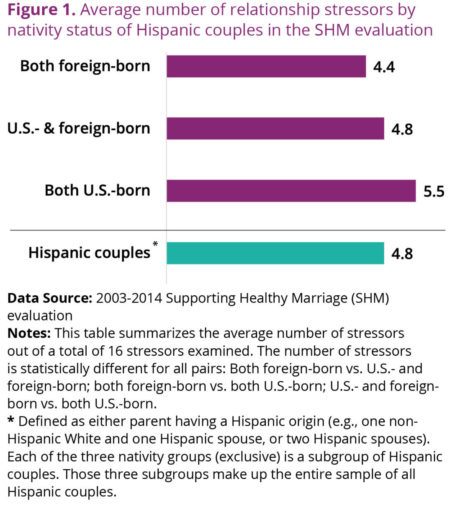

- The Hispanic couples in this sample faced multiple relationship stressors—factors that research has found can strain a couple’s relationship quality. Among the 16 stressors we examined, Hispanic couples reported having 4 to 5 stressors on average.

- The total number of stressors was the highest among U.S.-born couples (5.5), followed by mixed nativity couples (4.8).

- Foreign-born couples reported the fewest stressors, on average (4.4).

- Overall, housing hardship (68%), having stepchildren (47%), and having poor/fair health (40%) were the most common stressors reported by the Hispanic couples in this sample. In general, foreign-born Hispanic couples differed from U.S.-born and mixed nativity couples in the types and prevalence of stressors. The prevalence of most stressors was lower among foreign-born couples than the other groups. However, foreign-born couples had relatively high rates of neither partner having a high school education (30%) and neither having any emergency or emotional support other than their partner (35%).

Implications

- To support families most effectively, it is critically important to pay attention to factors inside and outside the romantic relationship. The high prevalence of relationship stressors among a sample of Hispanic couples seeking HMRE services suggests that HMRE programs may be more successful at impacting some of the longer-term programmatic outcomes—such as relationship stability and child well-being—if they support relationship skill building while also addressing other, often more pressing, stressors in couples’ lives. The positive relationship dynamics that can emerge from HMRE programming are important for healthy romantic relationships but may not be able to overcome the pressure of other relationship stressors.

- To support families most effectively, it is critically important to pay attention to factors inside and outside the romantic relationship.

- Some stressors we examined cannot be eliminated, but they can inform how programs design and deliver their services. For example, a program cannot change a background of trauma, but it can ensure that its services are trauma-informed and refer participants to mental health professionals when appropriate.

- Other stressors (e.g., housing hardship or poor health) can be addressed via other social service programs, such as TANF, Medicaid, or subsidized housing. More streamlined integration of these varied social services programs could ease accessibility for many Latino families—especially families with foreign-born members—who often face administrative barriers (including immigration status restrictions) and burdens in accessing services.5,6,7 Other social services programs working with Latino families employ approaches—such as the New Mexico TANF program’s use of immigration ambassadors to navigate complexities around immigration status—that can be adopted by other social services programs.8

- This brief focuses on relationship stressors identified in prior research and included in the SHM dataset and not on the factors and dynamics within Latino families—cultural, relational, intrapersonal—that help many Latino families thrive, especially in the context of the systematic (e.g., policies limiting access to public services based on family immigration status) and personal discrimination experienced by Hispanic populations in United States. Future evaluation efforts might incorporate some of these strength-based measures into their data collection efforts to get a more comprehensive, and less deficit-based, perspective of how Latino families in the United States are functioning.

Data, Sample, and Methods

Data

Data for the analysis came from the 2003-2014 Supporting Healthy Marriage (SHM) evaluation. The SHM was the first federal, large-scale, randomized evaluation of HMRE programs for low-income couples with or expecting children who identified as married. Yearlong SHM programs were implemented in 10 locations in eight states across the United States. All sites offered (a) structured curricula in group workshops, (b) supplemental activities to reinforce workshop themes, and (c) referrals for other family needs. Eight of the 10 sites served couples with children under age 18 (or 73% of all couples), while two focused specifically on pregnant and expecting parents.

The SHM evaluation collected data from 6,298 couples, or 12,596 individuals, who sought and were eligible for SHM services, and who were randomly assigned to treatment and control groups in each site. Evaluation enrollment began in early 2007 and ended in late 2009, and the evaluation tracked couples for 30 months following enrollment.

Sample

For this analysis, we used data on Hispanic couples from the baseline and child longitudinal data sets and included respondents in the control and treatment groups. The baseline dataset included information from both spouses participating in the evaluation. The child longitudinal data included information on all children in each household at baseline and at the 12- and 30-month follow-ups. Because the programs in this evaluation worked with couples, we selected the couple as our unit of analysis.

We limited our sample to Hispanic couples enrolled in the evaluation from the eight sites that served participants with children (n=2,963).b Hispanic couples were defined as those in which both partners reported ethnicity and nativity status, and at least one partner self-identified as Hispanic. Prior analysis revealed that Hispanic couples in the SHM evaluation were, on average, somewhat younger and more likely to have both partners born in the United States than the general population of low-income Hispanic couples in the United States during the same time frame.6 In addition, we eliminated 42 observations in which more than two-thirds of the 16 stressors we examined were missing, resulting in a final sample of 2,921 Hispanic couples.

These data are a valuable source of information for social services programs serving Latino individuals and families. Marriage is relatively common among Hispanic populations eligible for services, and 40 percent of participants in the SHM evaluation identified as Hispanic.9 Although the Hispanic couples included in these data differed somewhat from U.S. couples in the general population, the data included a large proportion of couples who lived in households with more limited income and were potentially eligible for a wide range of federally funded programming.10

Measures

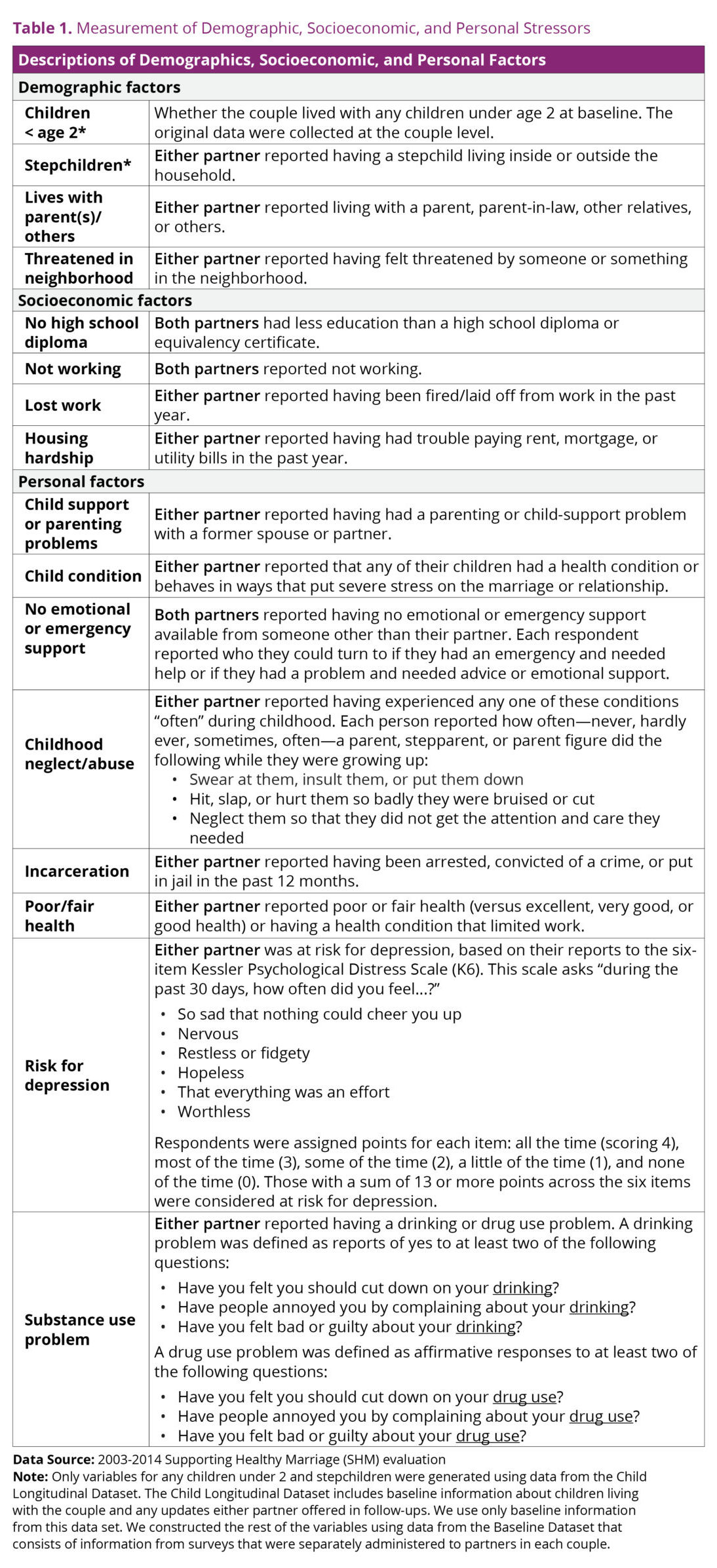

We focused our analysis on the socioeconomic, demographic, and personal factors research has linked to poorer relationship quality and dynamics in the general population and that were included in the SHM data.4

- Demographic stressors included the presence of infants and toddlers or stepchildren, co-residence with persons other than the nuclear family (which may provide some extra supports but has been linked to relationship stress), the presence of child health or behavioral issues, and neighborhood disadvantage.11,12,13,14,15,16,17,18

- Socioeconomic stressors included earnings, housing hardships, employment, and education.21,25,19,20,21,22,23

- Personal characteristics included incarceration history, mental and physical health status, substance (mis)use, and lack of social support.21,24,25,26

Table 1 lists the specific measures we used in this analysis; variables with an * indicate those that come from the child longitudinal data, while the remainder come from the baseline data. Data were collected from both partners, and we combined their reports to create couple-level measures as detailed below. We also used imputed variables from the evaluation in cases with missing reports.c Most measures captured if either partner reported a stressor, though a few measures required both partners to report it (education level, not working, and no emotional or emergency support).

Analytic Approach

To provide context, we first summarized basic demographic characteristics of the Hispanic couples in the sample and showed their responses to two questions about relationship distress. We then detailed the prevalence of the demographic, socioeconomic, and personal factors that can operate as stressors to a couple’s relationship. Importantly, we considered nativity status in our analysis. For immigrants, the conditions of sending and receiving countries influence families, their economic circumstances, and the kinds and levels of hardships they face.27,28 Although immigrants are resilient, having to adjust to a new environment adds another layer of complexity to couple relationships.29,30,31

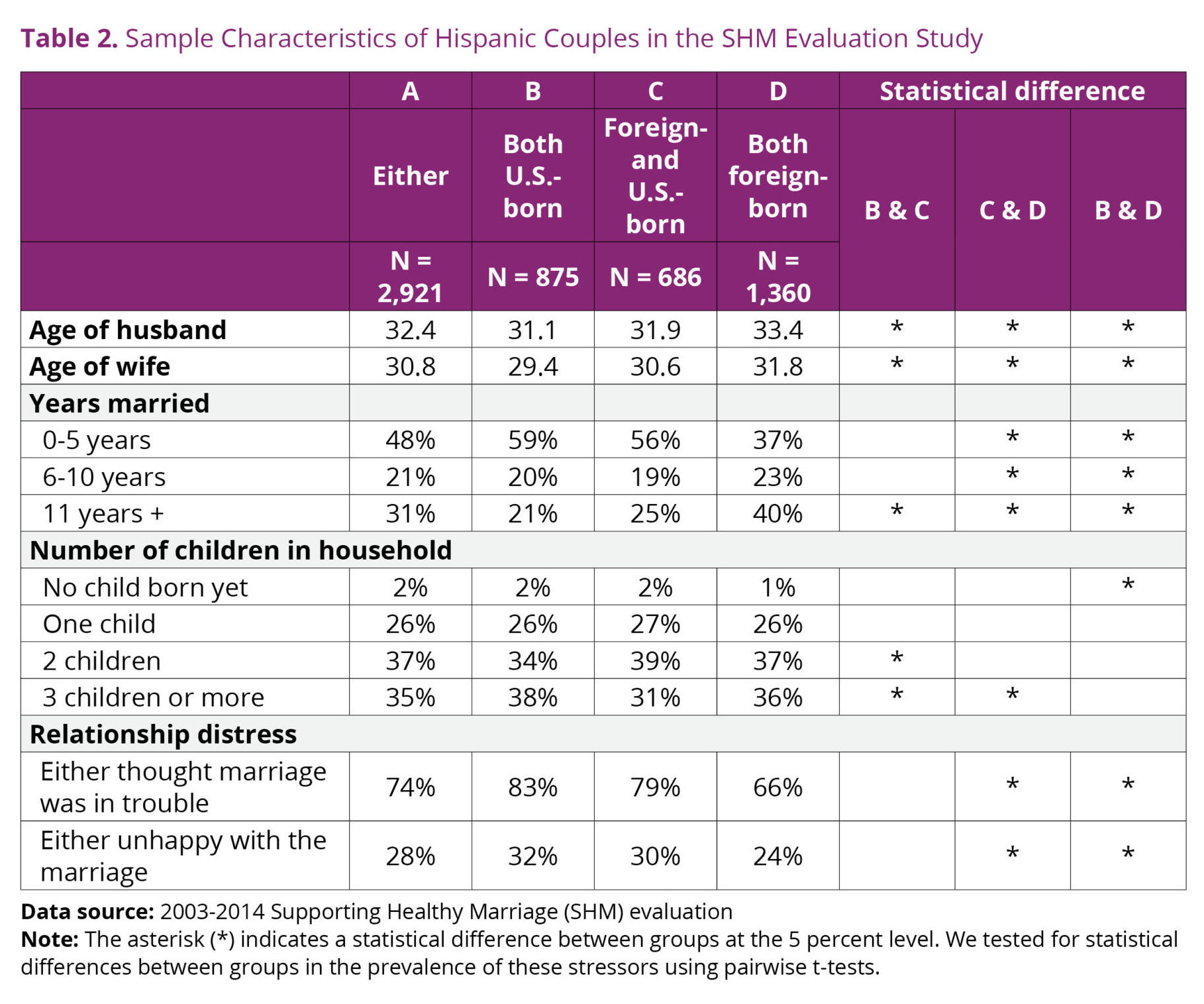

We showed the prevalence of these measures for all Hispanic couples and then separately by nativity status, distinguishing couples in which (1) both partners are U.S.-born (U.S. born couples) (N = 875; 30% of the sample), (2) one partner is U.S.-born and the other is foreign-born (mixed nativity couples) (N = 686; 23%), and (3) both are foreign-born (foreign-born couples) (N = 1,360; 47%). We tested for statistical differences in the prevalence of these stressors. Finally, to get a sense of the overall stress burden among the couples, we showed the average number of reported couple level stressors. We presented descriptive statistics conditioning on non-missing values throughout our analysis, except for one variable—the total number of stressors. To count stressors, we first imputed means by nativity status for missing values in each stressor variable before we summed up across stressors.

Results

Sample characteristics

Women in the sample were 31 years of age, on average, while men were 32. Individuals in U.S.-born couples were the youngest, on average. Approximately half the couples in the sample had been married for less than five years, while more than a fifth had been married for 6 to 10 years. Foreign-born couples were married longer, on average, than U.S.-born or mixed nativity couples. Overall, almost all couples had children in the household; only 2 percent had none and were expecting children. More than one-third of couples had three or more children, although this was somewhat lower among mixed nativity couples.

Looking at relationship distress, we found that approximately 3 in 10 of the couples in our sample had at least one partner who reported they were not happy with their marriage. However, almost three-quarters of the couples had at least one partner who thought their marriage was in trouble in the past year. Foreign-born couples were significantly less likely than U.S.-born or mixed nativity couples to report being unhappy in their marriage or that their marriage was in trouble.

Relationship stressors

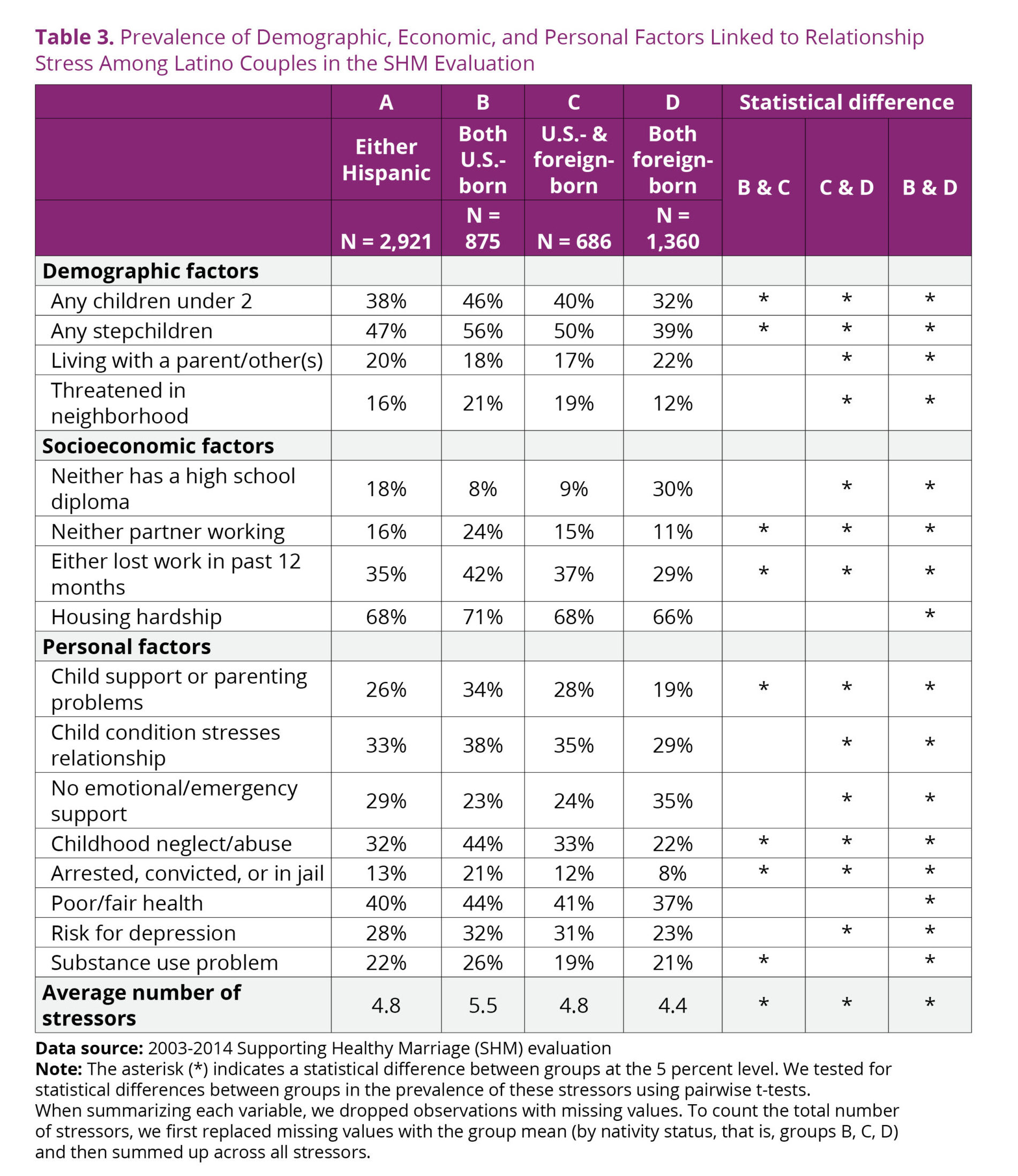

Table 3 details the prevalence of the measured demographic, socioeconomic, and personal stressors among Hispanic couples in our sample. Overall, housing hardship (68%), having stepchildren (47%), and having poor/fair health (40%) were the most common stressors reported by the Hispanic couples in this sample. In general, foreign-born Hispanic couples stood out from U.S.-born and mixed nativity couples in the types and prevalence of stressors. The prevalence of most stressors was lower among foreign-born couples than the other groups. However, foreign-born couples had relatively high rates of neither partner having a high school education (30%) and neither having any emergency or emotional support other than their partner (35%).

Demographic stressors

Overall, close to 4 out of 10 of the Hispanic couples in our sample had children under the age of 2; this was more prevalent among U.S.-born couples (46%) than mixed nativity or foreign-born couples. Additionally, many Hispanic couples had complex families or lived in complex households; 47 percent of couples reported having at least one stepchild living in or outside their households, and 20 percent lived in a household with a parent, in-law, or other adults. Notably, 56 percent of U.S.-born couples had a stepchild compared to 39 percent of foreign-born couples. Conversely, foreign-born couples were more likely to be living with a parent or other adults (22%) than U.S.-born and mixed nativity couples (17% and 18%, respectively). A sizable minority of Hispanic couples (16%) reported feeling unsafe in their neighborhood, although this was much more common among U.S.-born (21%) and mixed nativity (19%) couples than among foreign-born couples (12%).

Socioeconomic stressors

Of the four socioeconomic stressors included in this analysis, experiencing job loss in the past 12 months and housing hardships were the most common. One-third of couples reported that at least one partner lost a job in the past year, although this was most common among U.S.-born couples (42%). Slightly more than two-thirds of couples reported that they had trouble paying their rent, mortgage, or utilities in the past year, and this was relatively similar across the separate groups. Foreign-born couples were more likely to report having neither partner having at least completed high school (30%), although they were also the least likely to report that neither partner was working (11% compared to 24% of U.S.-born couples and 15% of mixed nativity couples).

Personal stressors

We looked at the prevalence of eight personal stressors in this analysis. Of the measures related to children, one-quarter of Hispanic couples noted that they experienced parenting or child support issues with a prior partner, while one-third reported having a child with a health or behavioral condition that stressed their marriage. These stressors were less common among foreign-born couples than among U.S.-born or mixed nativity couples.

About 3 out of 10 Hispanic couples reported not having anyone other than their partner to turn to for emotional or emergency support, and this was significantly higher among foreign-born couples (35%) than other couples (roughly 24%). Notably, close to one third of the couples in the sample reported that at least one partner often experienced at least one of three abuse or neglect conditions while they were growing up. This was significantly more prevalent among U.S.-born (44%) and mixed nativity couples (33%) than among foreign-born couples (22%). Similarly, U.S.-born (21%) and mixed nativity couples (12%) were more likely than foreign-born couples (8%) to report having at least one partner who was arrested, convicted, or jailed in the past year.

Overall, 40 percent of Hispanic couples reported poor/fair health (or the presence of a health condition that limited work); 22 percent reported some sort of substance use problem; and 28 percent reported being at risk for depression. U.S.-born couples reported higher prevalence of poor/fair health and being at risk for depression than foreign-born couples, with mixed nativity couples falling in between.

Average number of stressors

The final row in Table 3 shows the average number of stressors reported by the couples. Hispanic couples reported an average of 4.8 stressors among the 16 examined in this analysis. The total number of stressors is the lowest among foreign-born couples, averaging about 4.4 stressors, and highest among U.S.-born couples, averaging 5.5 stressors. The average number of stressors reported by mixed nativity couples (4.8) falls in between the number of stressors for the other two groups.

Discussion

HMRE programs serve many individuals and couples who identify as Hispanic. Knowing more about the life circumstances and experiences that might impact the quality of relationships of Hispanic couples in HMRE programs can help ensure that programs have the information needed to make their content relevant for their clients’ needs. This is important because, although participant satisfaction with HMRE programs is generally high, HMRE programs have had limited impacts on relationship stability in the long term.

A rich body of family research documents the important role that the demographic, socioeconomic, and personal factors included in this analysis play in shaping relationship quality and the dynamics within relationships. Our analysis found that Hispanic participants in the HMRE programs included in the SHM evaluation reported about five of the stressors we examined. Additionally, the prevalence of most stressors varied by the couples’ nativity status. U.S.-born couples faced the highest total number of stressors examined, followed by mixed-status and then foreign-born couples. The prevalence of most stressors was also the highest for U.S.-born couples and the lowest for foreign-born couples, although foreign-born couples were the most likely to report living in a household with others, not having high school education, and not having anyone other than their partner to turn to for emotional or emergency support.

Both the broader research literature and our findings suggest that HRME programs may find additional success impacting some of the key program outcomes—such as relationship stability and child well-being—if they support relationship skills while also addressing other, often more pressing, stressors in couples’ lives. Future research should examine this possibility.

Some of the stressors Hispanic couples face can be addressed within existing HMRE programs (e.g., adapting or developing more robust program content targeting the needs of stepfamilies or new parents). Additionally, many programs are critical to building important social and emotional connections among families who attend. In fact, research finds that these social connections are one of the reasons that program attendees value HMRE programs so highly.32 This may be particularly important for foreign-born couples who report lower levels of social support in this analysis.

Some of the stressors can be addressed by other existing federal, state, and local social services programs that provide, for example, subsidies for housing and utilities, work training and placement, and public health insurance and health care. We know that many families in need, including Hispanic families, are not accessing many of these programs.33 Investing in more effectively integrating social services programs (e.g., same application process for multiple programs, automatic rereferrals) and in ensuring that barriers limiting accessibility to these programs for Hispanic families (particularly families with immigrant members) are removed would help ensure that more people receive services to help their families thrive. Additionally, successful strategies employed by some social services programs working with Latino families—such as immigration ambassadors used in the TANF program in New Mexico to help navigate complexities around immigration status—can be adopted by other social services programs.34 Similarly, case managers or social service navigators can help facilitate access to and coordinate supports and services across varied systems.35

However, some of the stressors we examined cannot be eliminated, but they can help inform how programs design and deliver their services. For example, a program cannot change a background of trauma, but it can ensure that its services are trauma informed, and it can refer participants to mental health professionals when appropriate. Programs must try to understand the stressors their participants face and then identify and implement evidence-based strategies that are appropriate and effective in supporting families in the context of these stressors.

This research also has important implications for the outcome measures HMRE programs or funders choose to monitor. The primary outcomes of interest for most programs (that have been evaluated) generally focus on relationship knowledge/attitudes/beliefs and relationship quality.36 Other outcomes, including those related to some of the stressors measured in this brief (e.g., physical and mental health), are sometimes measured but not nearly as often. Given the importance of these factors for relationship well-being (as well as other outcomes more broadly), programs should consider monitoring some of these outcomes as well.

Limitations

It is important to note that this brief focused on the presence of relationship stressors identified in prior research and that were included in the SHM data set. We did not focus on the presence of the many factors and dynamics within Latino families—cultural, relational, intrapersonal—that, according to research, help Latino families thrive, especially in the context of the systematic oppression and discrimination that leads to many of the stressors we did examine.20 In a few cases, the lack of a stressor (e.g., having someone to turn to for social support) can be viewed as a strength. In most cases, however, the lack of a stressor does not represent the presence of the factors that help Latino families (or any family) thrive. It would be useful for future evaluations to also incorporate strength-based measures into their data collection efforts to get a more comprehensive, and less deficit based, perspective of how Latino families in the United States function and what resources and strategies can be leveraged to help them thrive.

Additionally, we acknowledge that the data included in this evaluation are now roughly a decade old, and some of the data were collected during the Great Recession, a period of economic uncertainty. That said, even with some post-recession economic rebound, in the past decade the country has continued to experience large-scale economic, political, and health events that have exacerbated the stressors to which many populations, especially Hispanic populations, are exposed. Thus, Hispanic families with low incomes are still likely to be experiencing many of the same stressors included in this analysis. For example, anti-immigration policies in the mid-2010s increased distrust among foreign-born Hispanic populations, mixed-status families, and Hispanic communities.37 And the COVID-19 pandemic took a particularly hard toll on Latino families—in terms of job loss, lost wages, and health38— and economic uncertainty for Latino workers, in particular women, remains higher than average post-COVID.39

Despite its limitations, the SHM evaluation resulted in one of the few large scale data sets that provide rich information on couples’ relationships, especially Latino couples. Our findings suggest that many families seeking HMRE services face multiple co-occurring stressors that affect their family well-being. These analyses would ideally be replicated with nationally representative data. However, nationally representative data that look at key factors inside and outside couples’ romantic relationships remain limited.

Footnotes

a We use “Hispanic” and “Latino” interchangeably throughout the brief. This usage is consistent with the U.S. Census definition and includes individuals having origins in Mexico, Puerto Rico, and Cuba, as well as other “Hispanic, Latino, or Spanish” origins.

b The 10 SHM sites included two sites in Washington, Texas, and Pennsylvania and one site in Kansas, Oklahoma, New York, and Florida. The site in Oklahoma and one of the two sites in Washington served mostly couples who were expecting children. Couples in the two sites that focused on expecting parents were more likely to be non-Hispanic White, U.S.-born, have higher levels of education, less likely to live in poverty, and were younger, on average, than couples in other sites. About 28 percent of couples in these two sites had at least one partner who was Hispanic, compared to 64 percent of couples in other sites.

c We employed multiple strategies to reduce missingness in the covariates. First, we used couple-level imputed variables by the evaluator when those variables were aligned with our intended construction (e.g., the couple-level imputed variable for either partner being at risk for depression). Second, we used person-level imputed variables to construct our couple-level variables for analysis (e.g., we created the couple-level variable for both partners not working using person-level imputed variables for work status). Third, we first replaced missingness in person-level reports with an affirmative category from the couple-level imputed indicator for both partners having a characteristic and then used these revised person-level reports to construct the couple-level variable that we desired (e.g., we considered each partner having a high school education if the imputed probability for both having a high school diploma was greater than 0.5). Fourth, we used only person-level reports to construct variables for either having a characteristic and assigned missingness to (1) couples in which both had missing reports, and (2) one partner did not have this characteristic and the other partner did not report. We assigned an affirmative category to couples in which one had this characteristic, and the other did not report. We followed the same logic to generate variables for both partners having a characteristic.

Suggested Citation

Wildsmith, E., & Chen, Y. (2023). Relationship Stressors among Latino Families in the Supporting Healthy Marriage Evaluation. Bethesda, MD: National Research Center on Hispanic Children & Families. https://doi.org/10.59377/914m2879v

Acknowledgements

The authors thank the Steering Committee of the National Research Center on Hispanic Children & Families—along with Allison Hyra, Kristen Harper, Tracy Gebhart, and Laura Ramirez—for their helpful comments, edits, and research assistance at multiple stages of this project. The Center’s Steering Committee is made up of the Center investigators—Drs. Natasha Cabrera (University of Maryland, Co-I), Danielle Crosby (University of North Carolina, Greensboro, Co-I), Lisa Gennetian (Duke University; Co-I), Lina Guzman (Child Trends and PI), Julie Mendez (University of North Carolina, Greensboro, Co-I), and Maria Ramos-Olazagasti (Child Trends and Building Capacity lead)—and federal project officers Drs. Ann Rivera, Jenessa Malin, and Minna Addo (Office of Planning, Research, and Evaluation).

Editors: Mark Waits and Brent Franklin

About the Authors

Elizabeth Wildsmith, PhD, is a research scholar at Child Trends and has worked with the National Research Center on Hispanic Children & Families since 2013. She is a family demographer whose research examines the process of marriage, cohabitation, and childbearing, as well as how social and family contexts may increase exposure to, or offer protection from, risk factors associated with the negative health and well-being of women, children, and families.

Yiyu Chen, PhD, is a research scientist at Child Trends. Her research examines how family structure is linked to child poverty and how antipoverty programs mitigate this relationship. Her recent studies center on child support, food assistance, the EITC, stimulus payments, and access barriers unique to Hispanic families and to families with low incomes.

About the Center

The National Research Center on Hispanic Children & Families (Center) is a hub of research to help programs and policy better serve low-income Hispanics across three priority areas: poverty reduction and economic self-sufficiency, healthy marriage and responsible fatherhood, and early care and education. The Center is led by Child Trends, in partnership with Duke University, University of North Carolina at Greensboro, and University of Maryland, College Park. The Center is supported by grant #90PH0028 from the Office of Planning, Research, and Evaluation within the Administration for Children and Families in the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services.

The National Research Center on Hispanic Children & Families is solely responsible for the contents of this brief, which do not necessarily represent the official views of the Office of Planning, Research, and Evaluation within the Administration for Children and Families, or the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services.

Copyright 2022 by the National Research Center on Hispanic Children & Families.

References

1 Herman-Stahl, M., & Scott, M. (2021). History and Implementation of the Federally Funded Healthy Marriage and Relationship Education (HMRE) Grants. Marriage Strengthening Research and Dissemination Center. http://mastresearchcenter.org/wp-content/uploads/2021/07/history-implementation-hmre-grants-aug-2021.pdf

2 Huz, I., Logan, D., Scott, M., & Wilson, A. (2020). Healthy Marriage and Relationship Education Evaluation Research: A Detailed Synthesis. Marriage Strengthening Research and Dissemination Center. https://mastresearchcenter.org/mast-center-research/healthy-marriage-and-relationship-education-evaluation-research-a-detailed-synthesis/

3 Wood, R. G., Moore, Q., Clarkwest, A., Killewald, A., & Monahan, S. (2012). The Long-Term Effects of Building Strong Families: A Relationship Skills Education Program for Unmarried Parents. OPRE Report #2012-28A. Washington, DC: Office of Planning, Research, and Evaluation, Administration for Children and Families, U.S. Department of Health and Human Services.

4 McLanahan, S., & Beck, A. N. (2010). Parental Relationships in Fragile Families. The Future of Children 20(2), 17-37. https://doi.org/10.1353/foc.2010.0007

5 Bitler, M., Gennetian, L. A., Gibson-Davis, C., & Rangel, M. A. (2021). Means-Tested Safety Net Programs and Hispanic Families: Evidence from Medicaid, SNAP, and WIC. The ANNALS of the American Academy of Political and Social Science, 696(1), 274–305. https://doi.org/10.1177/00027162211046591

6 Hayes, K. (2021). Eliminating Structural Barriers Can Improve Latino People’s Access to Health Coverage. Center on Budget and Policy Priorities. https://www.cbpp.org/blog/eliminating-structural-barriers-can-improve-latino-peoples-access-to-health-coverage

7 Barnes, C. Y., & Gennetian, L. A. (2021). Experiences of Hispanic Families with Social Services in the Racially Segregated Southeast: Views from Administrators and Workers in North Carolina. Race and social problems, 13(1), 6–21. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12552-021-09318-3

8 Finno-Velasquez, M., Gennetian, L., Sepp, S., & Deambrosi, S. (2021). Practitioners in New Mexico’s TANF Program Offer Perspectives on Engaging Hispanic Families. Report 2021-03. Bethesda, MD: National Research Center on Hispanic Children & Families. Retrieved from www.hispanicresearchcenter.org/research-resources/practitioners-in-new-mexicos-tanf-program-offer-perspectives-on-engaging-hispanic-families

9 Wildsmith, E., Scott, M., Guzman, L., & Cook, E. (2014). Family Structure and Family Formation among Low-Income Hispanics in the U.S. National Center on Hispanic Children and Families. https://www.hispanicresearchcenter.org/research-resources/family-structure-and-family-formation-among-low-income-hispanics-in-the-u-s/

10 Ramos-Olazagasti, M. A., & Guzman, L. (2018). Hispanic Couples in the Supporting Healthy Marriage Evaluation: How Representative are they of Low-Income Hispanic Couples in the United States? Bethesda, MD: National Research Center on Hispanic Children & Families. https://www.hispanicresearchcenter.org/research-resources/hispanic-couples-in-the-supporting-healthy-marriage-evaluation-how-representative-are-they-of-low-income-hispanic-couples-in-the-united-states/

11 Bulanda, J. R., & Brown, S. L. (2007). Race-ethnic differences in marital quality and divorce. Social Science Research, 36(3), 945–967. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ssresearch.2006.04.001

12 Cutrona, C. E., Russell, D. W., Abraham, W. T., Gardner, K. A., Melby, J. N., Bryant, C., & Conger, R. D. (2003). Neighborhood context and financial strain as predictors of marital interaction and marital quality in African American couples. Personal Relationships, 10(3), 389–409. https://doi.org/10.1111/1475-6811.00056

13 Guzzo, K. B., & Hayford, S. R. (2014). Fertility and the stability of cohabiting unions: Variation by intendedness. Journal of Family Issues, 35(4), 547–576. https://doi.org/10.1177/0192513X12468104

14 Högnäs, R. S., & Carlson, M. J. (2010). Intergenerational relationships and union stability in fragile families. Journal of Marriage and Family, 72(5), 1220–1233. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1741-3737.2010.00760.x

15 Jensen, T. M., Shafer, K., Guo, S., & Larson, J. H. (2017). Differences in relationship stability between individuals in first and second marriages: A propensity score analysis. Journal of Family Issues, 38(3), 406–432. https://doi.org/10.1177/0192513X15604344

16 Kvist, A. P., Nielsen, H. S., & Simonsen, M. (2013). The importance of children’s ADHD for parents’ relationship stability and labor supply. Social Science & Medicine, 88, 30–38. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.socscimed.2013.04.001

17 Moller, K., Hwang, P. C., & Wickberg, B. (2008). Couple relationship and transition to parenthood: Does workload at home matter? Journal of Reproductive and Infant Psychology, 26(1), 57–68. https://doi.org/10.1080/02646830701355782

18 Perini, T., Ditzen, B., Fischbacher, S., & Ehlert, U. (2012). Testosterone and relationship quality across the transition to fatherhood. Biological Psychology, 90(3), 186–191. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.biopsycho.2012.03.004

19 Amato, P. R. (2014). Does social and economic disadvantage moderate the effects of relationship education on unwed couples? An analysis of data from the 15-month Building Strong Families evaluation. Family Relations, 63(3), 343–355. https://doi.org/10.1111/fare.12069

20 Lichter, D. T., Qian, Z., & Mellott, L. M. (2006). Marriage or dissolution? Union transitions among poor cohabiting women. Demography, 43(2), 223–240. https://doi.org/10.1353/dem.2006.0016

21 Maume, D. J., & Sebastian, R. A. (2012). Gender, nonstandard work schedules, and marital quality. Journal of Family and Economic Issues, 33(4), 477–490. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10834-012-9308-1

22 Sassler, S., & McNally, J. (2003). Cohabiting couples’ economic circumstances and union transitions: A re-examination using multiple imputation techniques. Social Science Research, 32(4), 553–578. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0049-089X(03)00016-4

23 Weisshaar, K. (2014). Earnings equality and relationship stability for same-sex and heterosexual couples. Social Forces, 93(1), 93–123. https://doi.org/10.1093/sf/sou065

24 Cranford, J. A., Floyd, F. J., Schulenberg, J. E., & Zucker, R. A. (2011). Husbands’ and wives’ alcohol use disorders and marital interactions as longitudinal predictors of marital adjustment. Journal of Abnormal Psychology, 120(1), 210–222. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0021349

25 Lehmiller, J. J., & Agnew, C. R. (2007). Perceived marginalization and the prediction of romantic relationship stability. Journal of Marriage and Family, 69(4), 1036–1049. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1741-3737.2007.00429.x

26 Turney, K. (2015). Hopelessly Devoted? Relationship Quality During and After Incarceration. Journal of Marriage and Family, 77(2), 480–495. https://doi.org/10.1111/jomf.12174

27 McKenzie, D., & Rapoport, H. (2010). Self-Selection Patterns in Mexico-U.S. Migration: The Role of Migration Networks. The Review of Economics and Statistics, 92(4), 811–821. https://doi.org/10.1162/REST_a_00032

28 Sullivan, D. H., & Ziegert, A. L. (2008). Hispanic immigrant poverty: Does ethnic origin matter? Population Research and Policy Review, 27(6), 667. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11113-008-9096-3

29 Cardoso, J. B., & Thompson, S. J. (2010). Common Themes of Resilience among Latino Immigrant Families: A Systematic Review of the Literature. Families in Society, 91(3), 257–265. https://doi.org/10.1606/1044-3894.4003

30 Greeff, A. P., & Holtzkamp, J. (2007). The Prevalence of Resilience in Migrant Families. Family and Community Health, 30(3), 189–200. https://doi.org/10.1097/01.fch.0000277762.70031.44

31 Johnson, M. D., Neyer, F. J., & Anderson, J. R. (2019). Development of Immigrant Couple Relations in Germany. Journal of Marriage and Family, 81(5), 1237–1252. https://doi.org/10.1111/jomf.12580

32 Meekin-Halpern, S. (2019). Social Poverty: Low-Income Parents and the Struggle for Family and Community Ties. NYU Press. https://nyupress.org/9781479891214/social-poverty/

33 Alvira-Hammond, M., & Gennetian, L. (2015). How Hispanic Parents Perceive Their Need and Eligibility for Public Assistance. Bethesda, MD: National Research Center on Hispanic Children and Families. https://www.hispanicresearchcenter.org/research-resources/how-hispanic-parents-perceive-their-need-and-eligibility-for-public-assistance/

34 Finno-Velasquez, M., Gennetian, L., Sepp, S., & Deambrosi, S. (2021). Practitioners in New Mexico’s TANF Program Offer Perspectives on Engaging Hispanic Families. Report 2021-03. Bethesda, MD: National Research Center on Hispanic Children & Families. Retrieved from www.hispanicresearchcenter.org/research-resources/practitioners-in-new-mexicos-tanf-program-offer-perspectives-on-engaging-hispanic-families

35 Di Biase, C., Mochel, M. (2021). Manhattan Strategy Group. Navigators in Social Service Delivery Settings: A Review of the Literature with Relevance to Workforce Development Programs. Chief Evaluation Office, U.S. Department of Labor. https://www.dol.gov/sites/dolgov/files/OASP/evaluation/pdf/NavigatorLitReview_20211203_508.pdf

36 Briggs, S., Wilson, A., Scott, M., & Logan, D. (2020). Outcomes and Outcome Domains Examined in HMRE Evaluation Studies. Marriage Strengthening Research and Dissemination Center. http://mastresearchcenter.org/wp-content/uploads/2020/08/MAST-Outcomes-brief_August-2020.pdf

37 Almeida, J., Biello, K. B., Pedraza, F., Wintner, S., & Viruell-Fuentes, E. (2016). The association between anti-immigrant policies and perceived discrimination among Latinos in the US: A multilevel analysis. SSM – Population Health, 2, 897–903. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ssmph.2016.11.003

38 Macias Gil, R., Marcelin, J. R., Zuniga-Blanco, B., Marquez, C., Mathew, T., & Piggott, D. A. (2020). COVID-19 Pandemic: Disparate Health Impact on the Hispanic/Latinx Population in the United States. The Journal of Infectious Diseases, 222(10), 1592–1595. https://doi.org/10.1093/infdis/jiaa474

39 Gilbert, K. (2022). How Does Economic Uncertainty Play Out at the Local Level? Kellogg Insight. https://insight.kellogg.northwestern.edu/article/economic-policy-uncertainty-state-and-local