Nov 8, 2023

Research Publication

National Profile of Latino Parents’ Educational Attainment Underscores the Diverse Educational Needs of a Fast-growing Population

Authors:

Introduction

Education plays a key role in facilitating socioeconomic mobility in the United States, both for individuals and for their children. Parents’ educational backgrounds are associated with their children’s life outcomes, including the children’s educational attainment and occupational success later in life.1

While the educational attainment of Black and White parents has been well-studied—along with this metric’s relationship to their children’s later educational and life outcomes—much less is known about the educational attainment of Latinoa parents. Yet Latino children represent the largest racial and ethnic minority group among children in the United States today, as well as a growing segment of the country’s future labor market, economy, and citizenry.2 Understanding the educational attainment of Latino parents is critical to understanding Latino families’ needs and how school systems can better support and engage them. It may also highlight challenges and opportunities in the U.S. educational (e.g., student retention and success), labor market (e.g., occupational segregation), and social safety net systems (e.g., job training and skill development programs).

This brief presents the first national portrait of the educational attainment of Latino children’s parents. We begin by comparing the parental education profiles of Latino children with at least one U.S.-born parent to those who live with immigrant-only parent(s). We do this for three reasons: First, while more than 90 percent of Latino children today were born in the United States, roughly half have a parent who is an immigrant.3 Second, the educational experiences of individuals differ based on where they completed their education. Third, children with parents born in the United States presumably have at least one parent who attended school in the United States and who is familiar with the U.S. education system.4,5 Following this comparison, we focus our analysis on the economic diversity within the Latino population. In this section, we examine how parental education levels vary with parental income: Parental education may be even more important for children in low-income families by serving as a conduit for economic mobility. Finally, we explore differences in the educational profiles of Hispanic children’s parents by elements of heterogeneity within the Latino population: parents’ country of heritage, English language proficiency, citizenship status, and time lived in the United States. Our analyses draw on one-year data from the 2019 American Community Survey.

Key Findings and Implications

Overall findings for all Latino children

- Just over half of Latino children have a parent whose highest level of education is at least some college experience; this ranges from some college credits without a degree through a bachelor’s degree or higher. Nearly 1 in 4 (23%) Latino children have a parent with a bachelor’s degree or higher.

- Still, for roughly 1 in 5 Latino children (21%), the highest level of education completed by a parent is less than a high school degree.

- Hispanic children with at least one U.S.-born parent have parents with significantly higher levels of education than their peers with no U.S.-born parents; for the latter, this reflects, in part, the educational experiences available in parents’ countries of origin. While 32 percent of Hispanic children whose parents were born outside of the United States have parents with at least some college experience, the most common highest level of parental education among this population is less than a high school degree (38%).

Findings by family income

- Parental education is generally lower among children whose families have low incomes, defined here as families with incomes below 200 percent of the official poverty threshold.

- About 2 in 5 Latino children in families with low incomes have parents whose highest level of educational attainment is at least some college experience, which includes some college credits without a degree through a bachelor’s degree or higher.

- The most common level of parental education for children in families with low incomes is a high school degree or GED.

- Differences in parental education between children with at least one parent born in the United States and those with no U.S.-born parents are somewhat smaller among Latino children in families with low incomes, relative to what we observed in the overall sample of Latino children irrespective of family income.

Findings by other features of Latino sociodemographic heterogeneity

The highest level of education completed by parents of Latino children varies by their country of heritage, English language proficiency, citizenship status, and generational status—factors that shape a family’s access to resources, the labor market, and their experiences in the United States.

- Hispanic children whose parents have Cuban, South American, or Spanish heritage tend to have parents with the highest levels of education. Approximately half of these children have parents whose highest level of education completed is a bachelor’s degree or higher.

- Latino children with parents who are reported to be proficient in English, who have U.S. citizenship, or who were born in the United States tend to have parents with higher levels of education than their counterparts.

Policy and program implications

- Latino parents may benefit from a range of adult education programs that align with their range of current education levels, including English as a second language (ESL) programs, job training and skill enhancement programs, GED programs for adults without high school degrees, and higher education for parents with high school diplomas. Such programs may support the economic security and mobility of Latino parents and their children.

- Parents who did not go through the U.S. education system themselves may need additional support navigating the K-12 school system with their children. Such supports might include learning how to advocate for their child and connecting them with other services in the community. K-12 schools can facilitate engagement via flexible scheduling of parent events, providing transportation and child care for events, providing materials in Spanish and Indigenous languages, creating opportunities for involvement with and for Latino parents, and training school personnel on engaging Latino parents.

- Higher education systems can demystify college for first-generation students and their parents by, for example, simplifying the financial aid process (and related communications), staffing bilingual financial aid counselors, providing materials in multiple languages, and offering parental engagement opportunities throughout the entire college experience.

Background

The mechanisms linking parental education and child development are interwoven and complex. Parents with higher levels of education, in general, have better labor market outcomes, which allow them to provide more material resources for their children, including access to better schools and more professional social networks, on which they can later draw.6 Additionally, stable job arrangements—gained in part through education and educational credentials—may facilitate parents’ investments in their children in other ways. Parents with higher levels of education tend to spend more time with their children and more frequently read to or with their children and help them with homework.7,8,9 U.S. educational systems also reinforce dominant middle class social norms that help students and their families smoothly navigate institutions and open up opportunities throughout the course of their lives.10

Parents’ educational attainment is shaped by their access to educational opportunities, whether in the United States or abroad, and varies widely among Latino parents in the United States. The educational opportunities available to Latino individuals also reflect resource inequities due to structural racism in the U.S. education system, including racial and ethnic segregation of schools,11,12 a property tax-funded school system,13 and residential segregation.14 For the approximately half of Latino children with a parent who is an immigrant, their parents’ educational opportunities were likely shaped by their country of origin and their timing of immigration to the United States.15 While immigrants tend to have higher levels of education than the rest of the population in their countries of origin,16,17 their educational experiences are also shaped by the social and economic conditions of that country. The push and pull factors that lead Latino immigrants and other immigrant groups to come to the United States (e.g., political volatility, natural disasters, and economic uncertainty abroad versus perceived economic opportunities in the United States) may help us understand the educational and economic opportunities that immigrant groups had available in their home countries, and, hence, their educational levels.18 Once in the United States, though, Latino immigrants—like immigrant groups who migrated to the United States before them—tend to experience educational mobility, with second- and higher-generation Latino adults acquiring more years of education than their first-generation peers.19,20

Findings

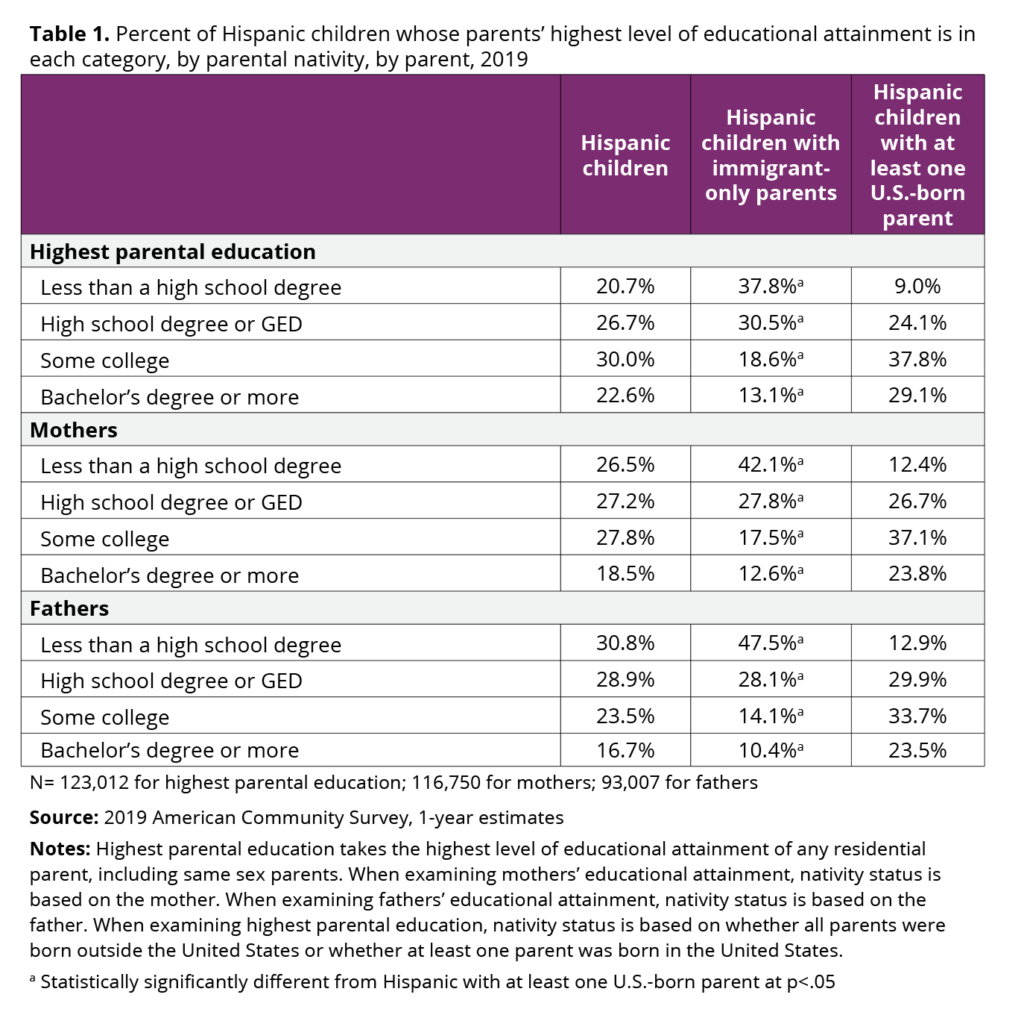

In this section, we look broadly at the education levels of parents of Latino children. Because patterns of parents’ education were similar whether we examined mothers’ education, fathers’ education, or highest parental education, we present highest parental education throughout this section. Results for mothers’ and fathers’ education are presented in the tables in the appendix.b

In our presentation of the findings, we focus on the proportion of children who have a parent with at least some college experience. This includes a wide range of educational experiences—from a single college credit, to an associate degree, to a bachelor’s degree or higher. While economic advancement is generally tied to degree completion, any college experience demonstrates some degree of cultural and navigational capital required to enroll in education beyond high school and register for classes, which may benefit a parent’s children.

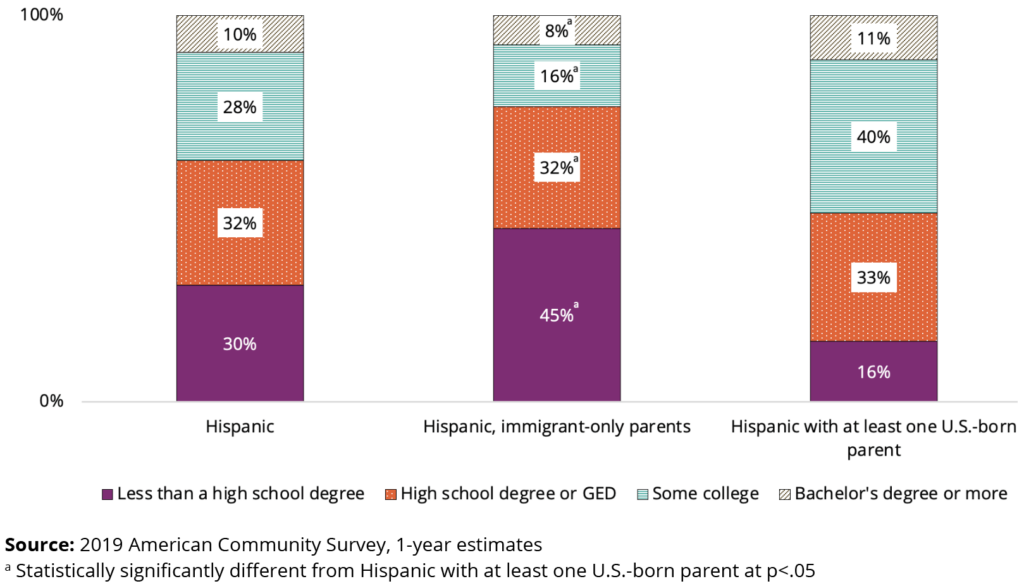

More than half of Latino children have a parent with at least some college experience

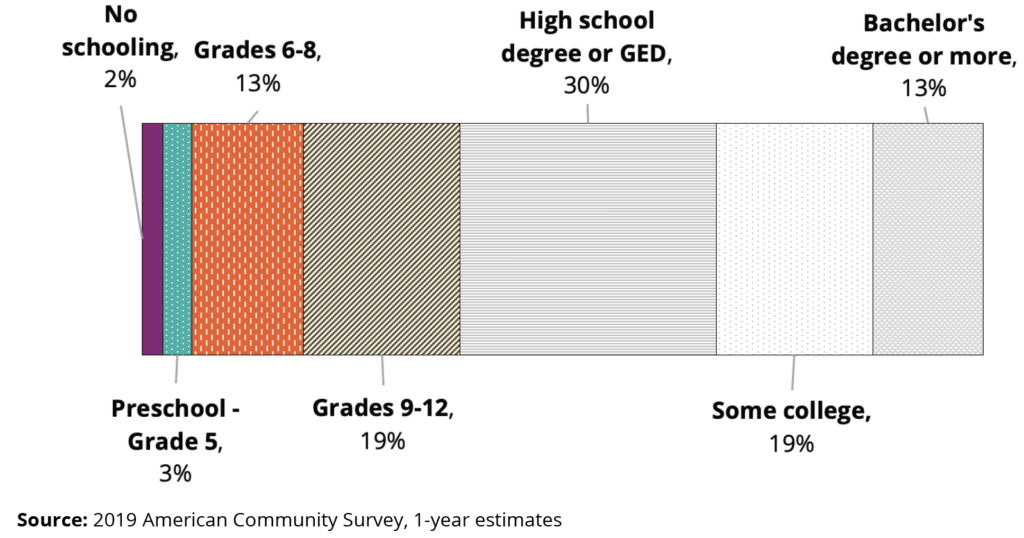

For 23 percent of Latino children, the highest level of education completed by their parents is a bachelor’s degree or higher; for an additional 30 percent, their parents have completed some college (see Figure 1 and Table 1). The highest level of parental education for 27 percent of Latino children is high school, while the parents of 21 percent of Latino children have completed less than a high school education.

Figure 1. While more than half of all Latino children have a parent with at least some college experience, the parents of 1 in 5 Latino children have not completed a high school degree.

Percent of Latino children whose parent’s highest level of educational is in each category, by parental nativity, ACS 2019

Hispanic children with at least one U.S.-born parent have parents whose highest level of educational attainment is significantly higher than their peers whose parents are all immigrants

Roughly one in three Latino children from immigrant families have parents with at least some college experience, including parents whose highest level of education is some college (19%) or a bachelor’s degree or higher (13%). Among those with at least one U.S.-born parent, two thirds have parents with at least some college experience; this includes 29 percent whose highest level of parental education completed is a bachelor’s degree or higher and 38 percent for whom the highest level of parental education is some college.

The most common highest level of parental education for Latino children with immigrant-only parents is less than a high school degree. Thirty-eight percent of Latino children with immigrant-only parents have parents whose highest educational attainment is less than high school. This is true for 9 percent of Latino children with at least one U.S.-born parent.

A closer look at children with immigrant-only parents

Hispanic children with immigrant-only parents have parents with lower levels of educational attainment, likely reflecting the social and economic conditions of the countries from which they immigrated. Thirty-eight percent of these children have parents whose highest level of education is less than a high school degree, including roughly one in five who have parents with an eighth-grade education or less.

Figure 2. More than one third of Hispanic children with immigrant-only parents have parents whose highest level of education is less than a high school degree, including roughly 1 in 5 whose highest education is eighth grade or less.

Percent of Hispanic children with immigrant-only parents whose parents’ highest level of educational attainment is in each category, ACS 2019

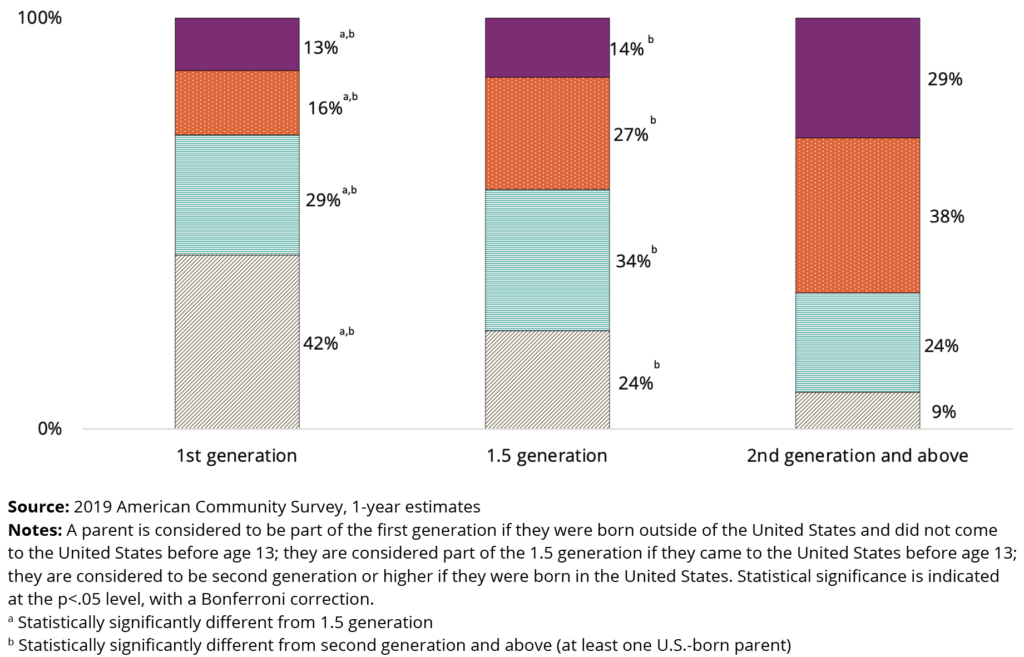

Parental education is generally lower among Hispanic children whose families have low incomes

Parental education levels for Hispanic children in families with low incomes—defined here as families with incomes below 200 percent of the federal poverty line—tend to be lower than for Hispanic children from higher-income families (at or above 200% of the federal poverty line). About two in five Latino children in families with low incomes have a parent with at least some college experience, including 10 percent with a parent holding a bachelor’s degree or higher and 28 percent with a parent who has some college. The most common level of parental education for children in families with low incomes is a high school degree or GED (32%), and about 30 percent of Hispanic children in these families have no parent with a high school degree.

We also looked at differences in parental education by whether a Latino child in a family with low income had at least one U.S.-born parent or had immigrant-only parents. Among families with low incomes, Hispanic children with at least one U.S.-born parent have parents who have completed higher levels of education than children with immigrant-only parents (see Figure 3 and Table 2).

Figure 3. While 2 in 5 Latino children in families with low incomes have a parent with at least some college experience, the most common level of parental education is a high school degree.

Percent of Latino children in families with low incomes whose parents’ highest level of educational attainment is in each category, by parent immigrant status, ACS 2019.

Findings by other features of Latino sociodemographic heterogeneity

In this section, we examine variations in parental education among Latino children by examining differences by parents’ country of heritage, reports of English language proficiency, citizenship status, and generational status—all factors that shape families’ access to resources and their experiences in the labor market.

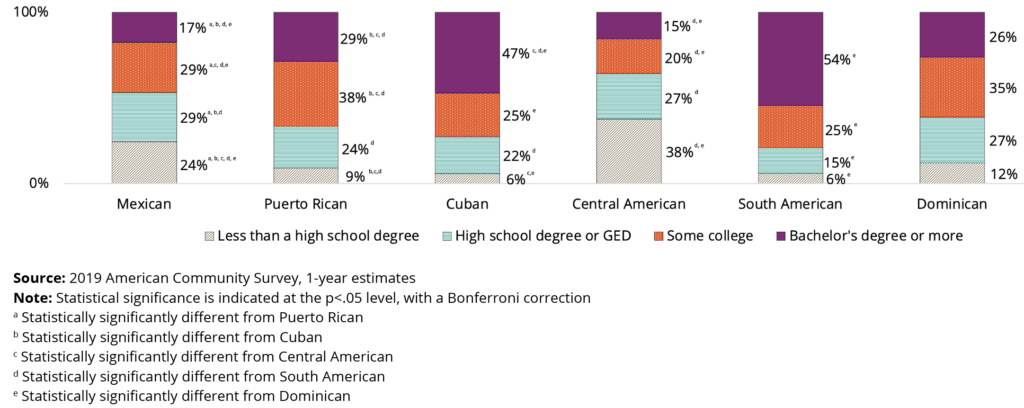

Parental educational attainment varies significantly by parents’ country of heritage

Among Hispanic children, parental educational attainment varies based on parents’ country of heritage (see Figure 4 and Table 3). Latino individuals of Mexican descent make up the largest group of Latino people in the United States, while those hailing from the Dominican Republic, Guatemala, Honduras, and Venezuela are among the fastest-growing groups of Latino people.21

Hispanic children whose parents have Cuban, South American, or Spanish heritage tend to have parents with the highest levels of education: About one half of children in these groups have a parent with a bachelor’s degree or more and another 25 percent have parents whose highest level of education is some college.

Latino children whose parents have Mexican or Central American heritage tend to have parents with lower levels of educational attainment than their counterparts. One in four children whose parents have Mexican heritage and more than one third of those whose parents have Central American heritage have parents whose highest level of education completed is less than high school. Conversely, 47 percent of children whose parents have Mexican heritage and 36 percent of children whose parents have Central American heritage have at least one parent with at least some college experience, which includes some college credits without a degree through a bachelor’s degree or higher.

Figure 4. The highest level of education completed by parents of Latino children varies by their parents’ country of heritage.

Percent of Hispanic children whose parents’ highest level of educational attainment is in each category, by parents’ country of heritage, ACS 2019

Latino children with parents who are proficient in English, have U.S. citizenship, or were born in the United States generally have parents who have completed higher levels of education.

Latino children with at least one parent who is reported to be proficient in English have parents with higher levels of education than their counterparts (see Table 4).c More than half of children whose parents are reported to be proficient in English have a parent with at least some college experience; 24 percent of Latino children whose parents are reported to have limited proficiency in English have a parent with some college experience. Almost half of Hispanic children with parents who are reported to have limited proficiency in English have parents whose highest level of educational attainment is less than high school; this is true for 10 percent of Hispanic children with parents who are proficient in English.

Similarly, Hispanic children whose parents are U.S. citizens tend to have parents with higher levels of educational attainment than those whose parents are not U.S. citizens (see Table 4). Parents who are not U.S. citizens include legal permanent residents, parents with temporary protective status, parents with other legal status to reside in the United States, and unauthorized immigrants. Two thirds of Hispanic children with U.S. citizen-only parents have a parent with at least some college experience, as do half of children with one parent who is a U.S. citizen and one parent who is not, and 22 percent of children with no U.S citizen parents. Nearly half (47%) of Hispanic children with no parent who is a U.S. citizen have parents whose highest level of education is less than a high school degree, as do 19 percent of those with one parent who is a U.S. citizen and one parent who is not, and 10 percent of children with U.S. citizen-only parents.

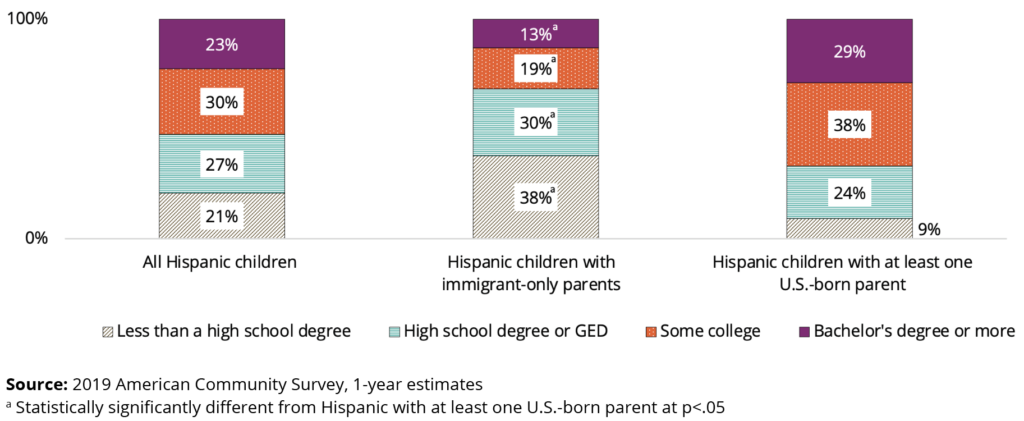

Parents’ highest levels of education are positively associated with the amount of time they have spent in the United States: Children whose parents immigrated as adults have parents with the lowest level of completed education, followed by children whose parents came to the Unites States as children (also known as 1.5 generationd), and then by children whose parents were born in the United States.

Forty-two percent of Hispanic children whose parents are first-generation have parents whose highest level of education completed is less than high school, as do one quarter of Hispanic children whose parents came to the United States as children and 9 percent among those with U.S.-born parents (see Figure 5 and Table 4). Conversely, two thirds (67%) of Hispanic children with U.S.-born parents have a parent with at least some college experience, as do 42 percent of Hispanic children whose parents came to the U.S. as children, and 28 percent of those with first-generation parents.

Figure 5. Hispanic children’s parental education levels increase with time spent in the United States.

Percent of Hispanic children whose parents’ highest level of educational attainment is in each category, by timing of parents’ immigration, ACS 2019

Discussion

This brief presents the first national portrait of the educational attainment of Latino children’s parents. We find that many Latino children have parents with some college experience, including nearly one quarter who have parents with a bachelor’s degree or higher. This is important because parental experience with higher education may ease children’s own transitions into higher education. At the same time, we find that one in five Latino children have a parent with less than a high school degree. These findings point to both opportunities and challenges for Latino families’ social and economic mobility and for the systems that serve them. Moreover, as has been historically the case with immigrant groups that have preceded them, we find that Latino parents’ educational levels vary by generational status (increasing with each generation), country of heritage (reflecting push and pull factors), and other features of Latino sociodemographic diversity. Notably, we find evidence of mobility, with parents of second or higher generations having higher levels of education than those who are first generation or who came to the United States as children.

Below, we present implications of our findings organized around a two-generation approach, starting with implications of parental education for parents’ own economic well-being and education, and then examining implications for parents’ involvement with their children’s education, both in the K-12 system and in higher education.

Family economic well-being. Education is an outcome in and of itself, but it is also strongly related to workforce opportunities and earnings potential. Earnings generally increase with education: Among Latino workers in the United States, ages 25-34, who worked full-time year-round, the average income in 2019 was $28,420 among those with less than a high school degree (just over the official poverty line for a family of four), compared with $35,370 for those with a high school degree, $39,370 for those with an associate degrees, and $50,160 for those with at least a bachelor’s degree.22 Although earnings increase as education levels increase, Latino parents are disproportionately represented in occupations in which jobs include nonstandard hours, limited provision of paid leave and health insurance, and low job stability23—conditions are not optimal to raising children. Taken together, programs and policies that support the educational opportunities and success of Latino students have the potential to offer benefits for Latino workers and their children. In the next section, we outline some promising practices to improve the K-12 and higher education systems for Latino families who have historically been disadvantaged through underfunded schools.24,25 However, while improved educational opportunities are necessary for social mobility, they are not sufficient. Policies and practices to combat discrimination and segregation in the labor market are also needed, as is increased access to benefits, higher wages, and predictable work schedules.

Adult education. The disparities in parental educational attainment within the Latino population point to a need for adult education opportunities—especially within immigrant communities. Given the diversity in Latino parents’ educational attainment, a range of adult education programs are needed, including English as a second language (ESL) programs, job training and skill enhancement programs, GED programs for adults without high school degrees, and higher education for parents with high school diplomas, and likely some college experience. However, many educational and job training programs were not designed for the unique needs of adult students, parenting students, Hispanic students, or immigrant students. As such, Latino parents may struggle to navigate educational systems not designed to serve them and programs may struggle to meet their needs.26,27,28

Family engagement with early care and education and the K-12 school system. Parents’ expectations, which are partly shaped by their own educational experiences, can promote their children’s educational outcomes.29 Latino parents have expectations for their children similar to those held by parents from other racial and ethnic groups.30 However, Latino parents’ aspirations may not as easily translate into high engagement with schools or homework, due, in part, to logistical barriers. Barriers include language barriers, limited time, and child care challenges; a lack of familiarity with the U.S. school system and an associated uncertainty about roles; and schools’ biased assumptions about Latino parents’ desires for involvement.31,32,33

Latino parents with lower levels of completed education—and especially those who did not go through the U.S. education system themselves—may engage with their children’s schooling in ways that go unrecognized by school staff, potentially perpetuating negative stereotypes.34 Schools can help Latino parents engage in their children’s school by creating a welcoming environment for them; this includes meeting Latino parents where they are, building trust with them, and recognizing them as peers and experts on their children.31,34,35 Specific promising strategies include flexible scheduling of parent events, providing transportation to and from events, providing child care at events, providing materials and communication in Spanish and Indigenous languages, explaining opportunities for involvement to Latino parents, and training school personnel—the latter includes training on working with parents as collaborators and on recognizing their involvement with their children’s education, both at home and at school.31,32 ,33 ,34 ,36

Family engagement with higher education. Latino students are the fastest-growing racial/ethnic group of college students.37 While the transition to college is a big transition for all young people, it can be especially tricky to navigate for students who are the first in their families to go to college—a category that includes many Latino students.33 Latino parents with and without college experience help their children prepare for and navigate higher education with moral and emotional support.38,39,40 Parents who have not gone to college themselves may be at a disadvantage in helping their children navigate a complex and stressful process.33

K-12 schools are a primary source of information on the college application process and financial aid for Latino students and parents, but families do not always receive the necessary, up-to-date information to make the jump to higher education.41,42 Financial instability is a top concern among Latino students.28,43 Many parents—and especially those who have not gone to college themselves or who have limited proficiency in English—struggle to understand and navigate the complex financial aid process. Higher education can simplify this process, from the FAFSA form itself to the ways in which offers are communicated,27 and some progress has been made with the FAFSA Simplification ACT that will take effect for the 2024-25 school year.44 Bilingual and culturally responsive financial aid counselors can also help ensure that parents are informed about how the process works.28 Further, institutions can provide materials in Spanish and other languages so that parents with limited English proficiency can read information themselves, removing a burden on students to act as translators.28 To facilitate parental engagement throughout a student’s educational career, schools can also offer parent engagement opportunities throughout the entire course of college, not just at orientation.40

Conclusion

As with all segments of the population, the educational attainment of Latino parents reflects the opportunities available to them. These opportunities, in turn, reflect structural factors, including the quality of schools in Latino families’ communities (whether in the United States or another country), their access to resources and opportunities to pursue a college education, policies (e.g., school funding, housing, loans, etc.) that facilitate the accumulation of family assets that afford or preclude the pursuit of education opportunities, and racism (among other factors). In the case of Latino parents who are immigrants, educational attainment also reflects the push (e.g., civil war, economic uncertainty) and pull (e.g., work opportunities) factors that lead Latino and other immigrant groups to come to the United States. These differences in opportunity manifest in differing levels of parental education by country of heritage, proficiency in English, U.S. citizenship, and time spent in the United States.

In many ways, the story of Latino populations in the United States mirrors that of other immigrant groups and the economic development of sending countries. Educational attainment among Latinos in the United States has been rising, a trend that is expected to continue. Indeed, the U.S. Hispanic population has seen sharp increases in both high school graduation and college enrollment rates.45 At the same time, the educational attainment of new immigrants has also been increasing over time, reflecting changes in sending countries’ educational opportunities and the countries of origin themselves.46 Given these rapidly changing conditions, repeated updates of educational profiles of Latino parents will help ensure that the education system meets the needs of this growing population.

Footnotes

a We use “Hispanic” and “Latino” interchangeably throughout the brief. The terms are used to reflect the U.S. Census definition to include individuals having origins in Mexico, Puerto Rico, and Cuba, as well as other “Hispanic, Latino or Spanish” origins.

b For those born outside of the United States, we do not know whether a parent received their schooling in the United States or in their country of origin.

c The survey respondent, who is typically the household head, reported on household members’ proficiency in English.

d We distinguish between those who came to the United States as children (1.5 generation) and those who came as adults because these two groups of immigrants differ in their exposure and familiarity with the U.S. education system. Those who are considered 1.5 generation typically went through some or all of their educational careers in the United States.

Suggested Citation

Ryberg, R., & Guzman, L. (2023). National profile of Latino parents’ educational attainment underscores the diverse educational needs of a fast-growing population. National Research Center on Hispanic Children & Families. DOI: 10.59377/665j6906g

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to thank the Steering Committee of the National Research Center on Hispanic Children & Families—along with Juan Manuel Pedroza, Kristen Harper, and Laura Ramirez—for their helpful comments, edits, and research assistance at multiple stages of this project. The Center’s Steering Committee is made up of the Center investigators—Drs. Natasha Cabrera (University of Maryland, Co-I), Danielle Crosby (University of North Carolina at Greensboro, Co-I), Lisa Gennetian (Duke University; Co-I), Lina Guzman (Child Trends, PI), Julie Mendez (University of North Carolina at Greensboro, Co-I), and Maria Ramos-Olazagasti (Child Trends, Deputy Director and Building Capacity lead)—and federal project officers Drs. Ann Rivera, Jenessa Malin, and Kimberly Clum (Office of Planning, Research and Evaluation).

Editor: Brent Franklin

Designers: Catherine Nichols & Joseph Boven

About the Authors

Renee Ryberg, PhD, is a senior research scientist in the education research area at Child Trends. Trained as a life-course sociologist and demographer, her work focuses on creating equitable environments to allow youth and young adults to thrive throughout their education and into adulthood.

Lina Guzman, PhD, is the principal investigator and director of the National Research Center on Hispanic Children & Families, where she oversees a broad research agenda; robust communication and capacity building activities, including efforts to build the pipeline of diverse scholars; and strategic partnerships with the research, policy, and practice community. She is chief strategy officer at Child Trends and serves as the director of the Child Trends Hispanic Institute. Her research focuses on describing the characteristics and experiences of diverse communities of Latinos living in the United States to help inform policies and programs.

About the Center

The National Research Center on Hispanic Children & Families (Center) is a hub of research to help programs and policy better serve low-income Hispanics across three priority areas: poverty reduction and economic self-sufficiency, healthy marriage and responsible fatherhood, and early care and education. The Center is led by Child Trends, in partnership with Duke University, University of North Carolina at Greensboro, and University of Maryland, College Park. The Center is supported by grant #90PH0028 from the Office of Planning, Research, and Evaluation within the Administration for Children and Families in the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services.

The National Research Center on Hispanic Children & Families is solely responsible for the contents of this brief, which do not necessarily represent the official views of the Office of Planning, Research, and Evaluation, the Administration for Children and Families, or the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services.

Copyright 2023 by the National Research Center on Hispanic Children & Families.

Data Source and Methodology

This brief used data from the 2019 American Community Survey (ACS), attained from IPUMS. The ACS—a nationally representative household survey—is conducted by the U.S. Census Bureau on a rolling basis, from January through December of each year.

For this brief, we began with all 640,382 children in the 2019 ACS 1-year sample. We then limited our analytical sample to Hispanic children under age 18 who live with at least one parent, for a final analytic sample of 123,012 Hispanic children living with at least one parent. Given our focus on children, we linked the characteristics of residential parents to each child record. Because families and households may have more than one child, some children in our sample resided in the same household. All analyses were conducted in Stata and weighted (using person-level weights) to be nationally representative.

We conducted descriptive analyses of parents’ education by immigrant status first across all income groups (Figures 1-2 and Table 1) and then for children living in families with low incomes (Figure 3 and Table 2). In our final set of analyses (Figures 4-5 and Tables 3-4), we examined parental education across a number of measures known to influence access to resources and the labor market, including country of heritage, English language proficiency, citizenship status, and generational status. Analyses by country of heritage have a smaller sample size than other analyses: For 6 percent of our sample of children identified as Hispanic, no residential parent identified as Hispanic.

We conducted analyses for mothers and fathers separately; given that the patterns in parents’ education were similar, we created a combined measure of highest level of parents’ education. We conducted tests of differences between groups based on parental characteristics, as applicable; significant differences are noted in the text and in the appendix tables. We corrected for multiple comparisons using a Bonferroni correction that uses a p-value of 0.05 divided by the number of comparisons. Where data allow, we present education profiles for Hispanic children’s mothers and fathers separately in the appendix tables below.

Below, we describe the measures used in our analysis. Throughout, parental measures are limited to residential parents.

Definitions

Parental education is classified into four categories for most analyses: less than high school, high school degree or GED, some college, and bachelor’s degree or more. Highest parental education takes the highest level of educational attainment of any residential parent, including same sex parents. Because of the relatively high percentage of Hispanic children with immigrant-only parents whose parents have less than a high school degree, we further break down the “less than high school degree” category to differentiate in some analyses between those who received no schooling, those with some schooling up to fifth grade, those whose education was completed in the sixth to eighth grades, and those with school experience into the ninth to 12th grades but who did not receive a high school degree or equivalent. Since respondents were asked to “report schooling completed in foreign or ungraded schools as the equivalent level of schooling in the regular American school system,” this measure does not differentiate between education received in the United States and in other countries. Finally, we recognize that some college includes a wide range of educational levels, ranging from taking one postsecondary class to obtaining an associate degree to being one class shy of a bachelor’s degree. There are some benefits to having an associate degree in comparison to some college without a degree, including a lower unemployment rate and higher earnings.47 However, for parsimony, we have included associate degrees within the some college category—and because both subcategories demonstrate experience with the higher education system.

Parental nativity is classified as having: 1) only parent(s) born outside the United States; or 2) having at least one U.S.-born parent. We also examined children with one U.S.-born and one immigrant parent separately from children with only U.S.-born parents (results not presented). While the overall patterns were similar, the biggest differentiator in our analyses was clearly having at least one U.S.-born parent.

Families with low incomes are identified as families with incomes below 200 percent of the official poverty threshold. In 2018, the federal poverty line for a family of four was $25,465 per year.48 Analyses limited to families with low incomes are limited to a sample size of 60,192 children.

Heritage. In the ACS, respondents are asked to indicate whether they are of Hispanic, Latino, or Spanish origin. If the answer is yes, they are asked to select between Mexican American; Puerto Rican; Cuban; or another Hispanic, Latino, or Spanish origin, with write-in options. The write-in options are then categorized into larger groups: Central American, South American, Spaniard, Dominican, and other. Central American includes Costa Rican, Guatemalan, Honduran, Nicaraguan, Panamanian, and Salvadoran. South American includes Argentinean, Bolivian, Chilean, Colombian, Ecuadorian, Paraguayan, Peruvian, Uruguayan, and Venezuelan. If two residential parents report different Hispanic heritages among the higher-level categories, they are categorized as having “multiple Hispanic heritages” in the main analyses.

English language proficiency. A child is considered to have at least one parent who is proficient in English if the survey respondent (typically the household head) reports that a residential parent speaks only English at home, or speaks a language other than English at home and speaks English very well. Because we are focused on parental human capital, we focus on parental language ability rather than a more general household measure.

U.S. citizenship. Parents’ U.S. citizenship status is categorized into three groups: 1) no residential parents are U.S. citizens, 2) one parent is a U.S. citizen and one is not, and 3) all residential parents are U.S. citizens. Parents who are not U.S. citizens include legal permanent residents, parents with temporary protective status, parents with other legal status to reside in the United States, and unauthorized immigrants.

Generational status. Parents’ generational status is categorized into three groups: 1) all parents are first-generation immigrants, 2) all parents are born outside the United States and at least one is a 1.5 generation immigrant, and 3) at least one parent is U.S.-born. A parent is considered part of the 1.5 generation if he/she came to the United States before age 13. Less than 1 percent of cases are reported as having come to the United States before birth. These cases are recoded as coming to the United States as infants.

Maternal measures are based on reports of mothers’ educational attainment, heritage, English language proficiency, citizenship, and generational status. Similarly, paternal measures are based on fathers’ educational attainment, heritage, etc. Highest parental education is based on all residential parents, including same sex parents, as are demographic characteristics when examining highest parental education.

References

1 Dubow, E. F., Boxer, P., & Huesmann, L. R. (2009). Long-term Effects of Parents’ Education on Children’s Educational and Occupational Success: Mediation by Family Interactions, Child Aggression, and Teenage Aspirations. Merrill-Palmer Quarterly (Wayne State University. Press), 55(3), 224–249.

2 The Annie E. Casey Foundation. (2022). Child population by race and ethnicity in the United States. KIDS COUNT Data Center.

3 National Center for Research on Hispanic Children and Families. (2020). Over 90 percent of all U.S. Latino children were born in the United States.

4 Batalova, J., Fix, M., Mittelstadt, M., & Zeitlin, A. M. (2016). Untapped Talent: The Costs of Brain Waste Among Highly Skilled Immigrants in the United States— Report in Brief. Migration Policy Institute, New American Economy, and World Education Services.

5 Mattoo, A., Neagu, I. C., & Ozden, C. (2005). Brain waste? Educated immigrants in the U.S. labor market. World Bank Policy Research Working Paper 3581.

6 Eccles, J. S. (2005). Influences of parents’ education on their children’s educational attainments: the role of parent and child perceptions. London Review of Education, 3(3), 191–204.

7 Guryan, J., Hurst, E., & Kearney, M. (2008). Parental Education and Parental Time with Children. Journal of Economic Perspectives, 22(3), 23–46.

8 Kalil, A., Ryan, R., & Corey, M. (2012). Diverging destinies: maternal education and the developmental gradient in time with children. Demography, 49(4), 1361–1383.

9 Cabrera, N. J., & Hennigar, A. (2019). The early home environment of Latino children: A research synthesis. National Research Center on Hispanic Children & Families.

10 Lareau, A. (2015). Cultural knowledge and social inequality. American Sociological Review, 80(1), 1-27.

11 Fuller, B., Kim, Y., Galindo, C., Bathia, S., Bridges, M., Duncan, G. J., & Valdivia, I. G. (2019). Worsening school segregation for Latino children? Educational Researcher, 48(7), 407-420.

12 Orfield, G., Ee, J. (2014). Segregating California’s Future: Inequality and its alternative 60 years after Brown V. Board of Education. The Civil Rights Project.

13 Baker, B. D., Di Carlo, M., Green, Preston C. III. (2022). Segregation and school funding: How housing discrimination reproduces unequal opportunity. Albert Shanker Institute.

14 Frey, W. H. (2021). Neighborhood segregation persists for Black, Latino or Hispanic and Asian Americans. Brookings Institution.

15 Federal Interagency Forum on Child and Family Statistics. (2022). America’s Children in Brief: Key National Indicators of Well-Being, 2022, Table FAM4. Government Printing Office.

16 Feliciano, C. (2005). Educational selectivity in U.S. immigration: How do immigrants compare to those left behind? Demography, 42(1), 131–152.

17 Lowell, B. L., & Suro, R. (2002). The improving educational profile of Latino immigrants. Pew Hispanic Center.

18 Hanson, G., Orrenius, P., & Zavodny, M. (2023). US immigration from Latin America in historical perspective. Journal of Economic Perspectives, 37(1), 199-222.

19 Antman, F. M., Duncan, B., & Trejo, S. J. (2023). Hispanic Americans in the labor market: Patterns over time and across generations. Journal of Economic Perspectives, 37(1), 169-198.

20 Gambino, C. (2017). Random samplings: Immigrant families and educational attainment. United States Census Bureau.

21 Krogstad, J. M., & Noe-Bustamante. (2021). Key facts about U.S. Latinos for National Hispanic Heritage Month. Pew Research Center.

22 National Center for Education Statistics. (2023). Median annual earnings of full-time year-round workers 25 to 34 years old and full-time year-round workers as a percentage of the labor force, by sex, race/ethnicity, and educational attainment: Selected years, 1995 through 2020. Digest of Education Statistics 2021. Institute of Education Sciences, U.S. Department of Education.

23 Wildsmith, E., Ramos-Olzagasti, M., & Alvira-Hammond, M. (2018). The job characteristics of low-income Hispanic parents. National Research Center on Hispanic Children & Families.

24 The Century Foundation. (2020). Closing America’s Education Funding Gaps.

25 Yuen, V. (2020). The $78 billion community college funding shortfall. Center for American Progress.

26 Lynn Lewis, N. & Haynes, D. (2020). National student-parent survey results & recommendations: Uncovering the student-parent experience and its impact on college success. Generation Hope.

27 Mwangi, C. A. G., Mansour, K., & Hedayet, M. (2021). Immigrant identity and experiences in U.S. higher education research: A systematic review. International Journal of Multicultural Education 23(2), 45-69.

28 Poppe, S. V. (2021). Following their drams in an inequitable system: Latino students share their college experience. UnidosUS.

29 Cross, F.L., Marchand, A. D., Medina, M., Villafuerte, A., & Rivas‐Drake, D. Academic socialization, parental educational expectations, and academic self‐efficacy among Latino adolescents. Psychology in the Schools, 56(4), 483-496.

30 Kim, Y., Sherraden, M., & Clancy, M. (2013). Do mothers’ educational expectations differ by race and ethnicity, or socioeconomic status? Economics of Education Review, 33, 82–94.

31 Arias, M. B., & Morillo-Campbell, M. (2008). Promoting ELL parental involvement: Challenges in contested times. Education Policy Research Unit and Education and the Public Interest Center.

32 Quiocho, A. M. L., & Daoud, A. M. (2006). Dispelling myths about Latino parent participation in schools. The Educational Forum, 70, 255-267.

33 Sosa, A. S. (1996). Involving Hispanic parents in improving educational opportunities for their children. In Children of La Fronters: Binational Efforts to Serve Mexican Migrant and Immigrant Students.

34 Poza, L., Brooks, M. D., & Veldés, G. (2014). Entre Familia: Immigrant parents’ strategies for involvement in children’s schooling. School Community Journal, 24(1), 119-148.

35 Delgado-Gaitan, C. (2007). Fostering Latino parent involvement in the schools: Practices and partnerships.

36 LeFevre, A. L., & Shaw, T. V. (2011). Latino parent involvement and school success: Longitudinal effects of formal and informal support. Education and Urban Society, 44(6), 707-723.

37 Mora, L. (2022). Hispanic enrollment reaches new high at four-year colleges in the U.S., but affordability remains an obstacle. Pew Research Center.

38 Auerbach, S. (2006). “If the student is good, let him fly”: Moral support for college among Latino immigrant parents. Journal of Latinos and Education, 5(4), 275-292.

39 Ceja, M. (2004). Chicana college aspirations and the role of parents: Developing educational resiliency. Journal of Hispanic Higher Education, 3(4), 338-362.

40 Rodriguez, S. L., Garbee, K., & Martinez-Podolsky, E. (2019). Coping with college obstacles: The complicated role of Familia for first-generation Mexican American college students. Journal of Hispanic Higher Education, 20(1).

41 Martinez, M. A., Cortez, L. J., & Saenz, V. B. (2013). Latino parents’ perceptions of the role of schools in college readiness. Journal of Latinos and Education, 12(2), 108-120.

42 Zarate, M. E., & Pachon, H. P. (2006). Perceptions of college financial aid among California Latino youth. The Tomás Rivera Policy Institute.

43 Elengold, K. S., Dorrance, J., & Agans, R. (2020). Debt, doubt, and dreams: Understanding the Latino college completion gap. The University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill and UNIDOS US.

44 Collins, B., & Dortch, C. (2022). The FAFSA Simplification Act. Congressional Research Service.

45 de Brey, C., Musu, L., McFarland, J., Wilkinson-Ficker, S., Diliberti, M., Zhang, A., Branstetter, C., & Wang, X. (2019). Status and Trends in the Education of Racial and Ethnic Groups 2018. (NCES 2019-038). U.S. Department of Education. National Center for Education Statistics.

46 Noe-Bustamante, L. (2020). Education levels of recent Latino immigrants in the U.S. reached new highs as of 2018. Pew Research Center.

47 Torpey, E. (2018). Measuring the value of education. Career Outlook. U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics.

48 U.S. Census Bureau. (2022). Poverty thresholds.