Oct 7, 2025

Data Point, Hispanic Child and Family Facts

One in Four Hispanic Children Live in Doubled-up Households

Authors:

One quarter (25%) of all Hispanic children live in doubled-up households, according to our new analysis of 2023 American Community Survey data. Doubled-up households are defined as those in which children live in households with their parents(s) and with other adults, who can include other relatives (e.g., a grandparent) and those who are unrelated.1

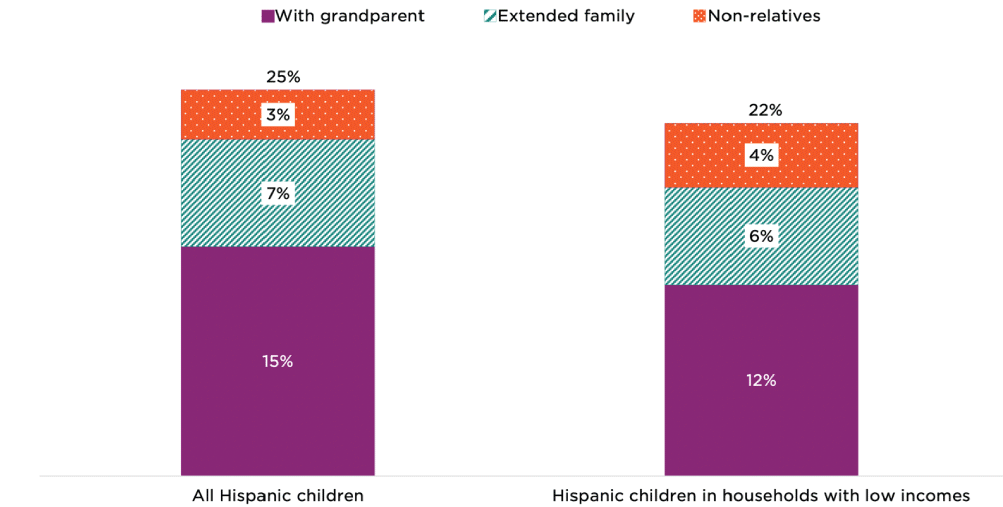

Doubling up with a grandparent is the most common among such arrangements: 15 percent of Hispanic children live with a parent and a grandparent, 7 percent live with a parent and some other extended family member, and 3 percent live with a parent and an unrelated adult. Relative to all Hispanic children, a slightly lower percentage (22%) of Hispanic children in households with low incomes are doubled-up. They are also slightly less likely to be doubled-up with a grandparent (12%) and somewhat more likely (4%) to be doubled-up with a non-relative.

Figure 1. One in four Hispanic children live in doubled-up households

Percentage of Hispanic children living in households with a parent and another adult, by type and household income

Source: Authors’ analysis of the Census Bureau’s 2023 American Community Survey and Puerto Rican Community Survey 1-Year data obtained via IPUMS USA, University of Minnesota, www.ipums.org.

Source: Authors’ analysis of the Census Bureau’s 2023 American Community Survey and Puerto Rican Community Survey 1-Year data obtained via IPUMS USA, University of Minnesota, www.ipums.org.

Notes: Sample includes Hispanic children under age 18 who were living with at least one parent, not living in group quarters, for whom data on poverty status and parental nativity were not missing, and who were not listed as head of household. Doubling up is defined as children (who live with at least one parent) who also live with any adult who is not their parent, their parent’s unmarried partner, or an adult sibling, and further categorized into doubled-up living with a grandparent, with extended family, or with non-relatives.

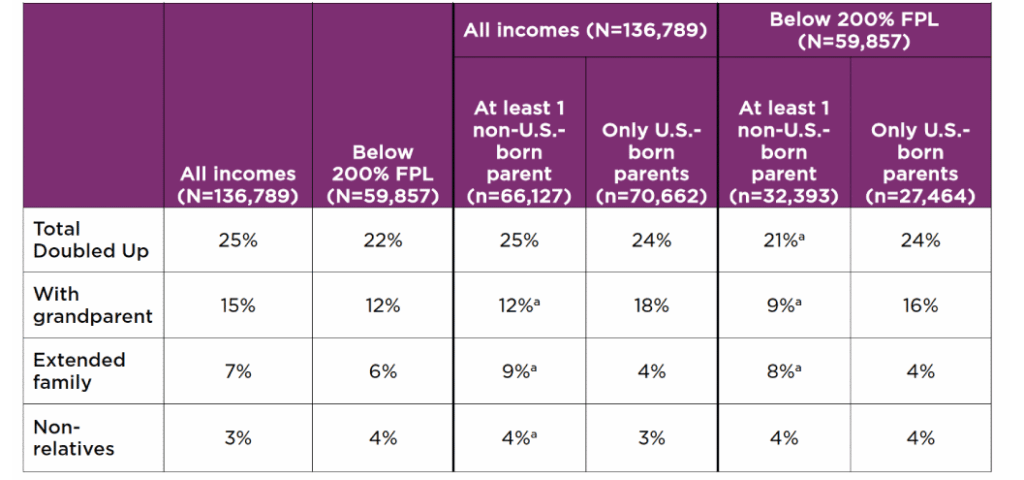

Hispanic children living in households with an immigrant parent(s) are as likely (25%) as those living with only U.S.-born parents (24%) to live in a doubled-up household (see Table A). However, the particular identity of these additional adults can vary quite substantially. Hispanic children living in households with at least one non-U.S.-born parent are more than twice as likely as those with only U.S.-born parents to also be living with an extended family member who is not a grandparent (9% vs. 4%), and slightly more likely to be living with a non-relative (4% vs. 3%). They are less likely to be living with a grandparent (12% vs. 18%). The patterns are similar for Hispanic children in households with low incomes.

Overall, the proportion of children in the United States living in doubled-up households has increased over the past several decades and is more common among Hispanic and Black children than among White children. Research suggests that these living arrangements are more common when a family is navigating economic pressures—such as low income, high housing costs, or unemployment—or when they have specific family needs related to, for example, caring for a young child or a family member in poor health. While doubling up can help families navigate some of their immediate economic stressors and family needs, it is also linked to increased residential instability, which can disrupt children’s schooling and their relationships with friends and caregivers.

However, who a family doubles up with can matter for children’s outcomes. Research finds that more time spent living with non-grandparent extended family or unrelated adults during one’s childhood is associated with relatively worse health and educational outcomes in young adulthood (relative to youth who did not live in doubled-up households); the same is not true for grandparent co-residence. And, as we have discussed in previous work, living with a grandparent—even one who may also need some caregiving support themselves—can expose children to valuable cultural traditions, family stories and history, and languages.

For children in households with low incomes, living in doubled-up arrangements can have implications for public assistance programs that support families’ economic self-sufficiency. For example, income from other adults in the household (besides the parent) may be counted toward a family’s eligibility for public assistance programs, such as Temporary Assistance for Needy Families (TANF), although this varies across states. Additionally, doubling up may signify a more pressing need for housing support. Given that the demand for rental assistance outpaces supply, some states have leveraged the flexibility of the TANF program to help families with children pay for their rent, utilities, and other housing-related necessities.

Methods

For this analysis, we used data from the U.S. Census Bureau’s 2023 nationally representative American Community Survey (ACS) and Puerto Rican Community Survey (PRCS) 1-year samples, obtained from IPUMS USA. We define Hispanic children as children under age 18 for whom a Latino, Hispanic, or Spanish origin was reported, regardless of their race. Our analytic sample includes Hispanic children under age 18 who were living with at least one parent and not living in group quarters, for whom data on poverty status and parental nativity were not missing, and who were not listed as head of household, resulting in a full unweighted sample of 136,789 Hispanic children.

Our measure of doubling up is defined as children (who live with at least one parent) who also live with any adult who is not their parent, their parent’s unmarried partner, or an adult sibling. We use the data’s parent pointers and household relationship markers to identify children in doubled-up households, and then to further identify whether any of those adults are a grandparent, another non-grandparent family member (extended family), or unrelated to the child. This approach is guided by that used by Amorim & Pilkauskas (2023) and Harvey, Dunifon, & Pilkauskas (2021) and treats each doubling up category as mutually exclusive, prioritizing doubling up with a grandparent first, followed by extended family, and then non-relatives. For example, if a child lives with their parent, a grandparent, and an unrelated adult, they are considered to be doubled up with a grandparent. For children whose parent is not the household reference person, we rely on the household rosters and the IPUMS household relationship markers to identify the child’s and their parents’ relationship to the household reference person. The IPUMS household relationship markers identify unmarried partners when one of the partners is the household reference person and the data’s parent pointers include unmarried partners of children’s parents. For cases in which none of the child’s parents are the household reference person, the data do not identify resident unmarried partners of a child’s parent. In some cases, this could result in a parent’s unmarried partner being identified as an unrelated adult; however, we expect this to affect only a small number of cases.

We created the category of families with low incomes using the IPUMS-constructed poverty variable, which calculates each person’s family income as a percentage of their family’s poverty threshold (see this summary of the poverty measure in IPUMS). We also show estimates according to whether children’s coresidential parents were born in the United States (i.e., their nativity) using two categories: 1) at least one parent in the household was born in another country or 2) all parents in the household are U.S.-born. For children with only one parent in the household, parental nativity was assigned based on the nativity of that parent alone.

Table A. Percentage of Hispanic children who are doubled up, by whether their parents were born in the United States, for all family incomes and for families with incomes below 200 percent FPL

Source: Authors’ analysis of the Census Bureau’s 2023 American Community Survey and Puerto Rican Community Survey 1-Year data obtained via IPUMS USA, University of Minnesota, www.ipums.org.

Source: Authors’ analysis of the Census Bureau’s 2023 American Community Survey and Puerto Rican Community Survey 1-Year data obtained via IPUMS USA, University of Minnesota, www.ipums.org.Notes: Sample includes Hispanic children under age 18 who were living with at least one parent, not living in group quarters, for whom data on poverty status and parental nativity were not missing, and who were not listed as head of household. Doubling up is defined as children (who live with at least one parent) who also live with any adult who is not their parent, their parent’s unmarried partner, or an adult sibling.

a Differences by parental nativity are statistically significant at p<0.001.

Suggested citation

Wildsmith, E., Alvira-Hammond, M. (2025). One in four Hispanic children live in doubled-up households. National Research Center on Hispanic Children & Families. DOI: https://doi.org/10.56417/9540p5652t

Footnote

1An unrelated adult household member is not the child’s parent, their parent’s unmarried partner, or an adult sibling.