Aug 4, 2025

Research Publication

Subsidy Application Policies to Support Working Families Vary Across Hispanic-Populous States

Authors:

Current federal and state Child Care and Development Fund (CCDF) dollars serve fewer than one in four children eligible for child care subsidies.1 While not all families eligible for CCDF need or seek out child care assistance, a recent study of CCDF implementation suggests that many families who could benefit from subsidies encounter barriers during the application and enrollment process2 For example, local CCDF staff report that parents must sometimes expend considerable time, effort, and resources to gather and submit application materials, which include various documents to verify their eligibility.2 Hispanic children, who make up one in four children in the United States,3 represent a large share of those who are eligible for child care subsidies, given their parents’ generally high levels of employment in the low-wage workforce.4 Yet in most states, Hispanic children are less likely than other eligible children to be served by the program.

Lead agencies in states and territoriesa (hereafter referred to as “states” for simplicity) have considerable flexibility to design their own CCDF programs, including decisions about how families apply for and become enrolled in the subsidy program. Streamlined application and enrollment procedures can minimize burdens for families (and program staff) and ensure efficient services that do not interfere with parents’ employment, education, or training—activities that promote their economic self-sufficiency. Recognizing this, federal regulations require that lead agencies implement “policies that minimize disruption to parent employment, education, or training opportunities.”5

In this brief, we highlight state-level variation in policies and procedures that affect the subsidy application process and consider how these may impact Hispanic families, who represent a large segment of the low-income workforce and those eligible for federal assistance programs. We focus on seven policy strategies, described below, related to reducing barriers and streamlining the subsidy application process that may make it easier for eligible working families, including Hispanic families, to access child care assistance. These strategies reflect both requirements and flexibilities outlined for lead agencies in federal statute (2014 CCDBG Reauthorization Act) or federal program guidelines (2024 Final Rule). Drawing on lead agencies’ descriptions of their CCDF program plans for fiscal years (FYs) 2025-2027, we summarize the extent to which these strategies are being used in Puerto Rico and 15 Hispanic-populous states that are home to more than 80 percent of Hispanic children in U.S. households with low incomes (hereafter “Hispanic-populous states”).3

Seven CCDF Policies That States May Implement to Reduce Barriers in the Child Care Subsidy Application Process

- Extended service hours. Lead agencies may choose whether to offer extended service hours to allow families to engage with staff in the evening or on weekends.

- Phone consultations. Lead agencies may choose whether to offer consultations to families by phone.

- Applications accepted at local community-based locations. Lead agencies may opt to accept subsidy applications at community-based locations (e.g., a local Child Care Resource and Referral agency).

To meet the federal requirement that CCDF enrollment policies minimize disruptions to employment, education, and training activities (CCDBG Reauthorization Act of 2014) and lessen the burden of CCDF administrative requirements on families, federal regulations encourage lead agencies to use the following four optional strategies (2024 Final Rule):

- Online subsidy application. Lead agencies are encouraged to offer an online application option to facilitate the enrollment process (2024 Final Rule). Lead agencies without an online application must explain in their CCDF plan why it is impracticable.

- Cross-program eligibility. Lead agencies are encouraged to leverage families’ participation in other public programs to determine or automatically grant eligibility for child care subsidies (2024 Final Rule). This practice is also sometimes referred to as “adjunctive financial eligibility” or “fast track” eligibility.

- Presumptive eligibility. Lead agencies are encouraged to use presumptive eligibility so that families who are likely eligible for subsidies can receive provisional authorization while the verification process is finalized (2024 Final Rule). Lead agencies opting to use this strategy can define the populations to whom it applies and the length of the presumptive eligibility period.

- Coordinated determinations for children in the same household. Lead agencies are encouraged to coordinate eligibility determinations for households with multiple children and align periods of eligibility (permissible as long as each child receives at least 12 months of eligibility).

About the Policies and Practices Shaping Child Care Subsidy Access in Hispanic-Populous States Series

The Child Care and Development Block Grant Act of 1990 (CCDBG), as amended in 2014, is the main federal law governing child care programs that support parents’ employment, families’ economic security, and children’s learning and development. Through the Child Care and Development Fund (CCDF) program, state, territory, and Tribal lead agencies receive federal CCDBG dollars to help subsidize eligible families’ child care expenses and improve the quality and supply of affordable care options in communities.

Federal CCDF regulations, as set forth in the CCDBG statute or the 2024 Final Rule, include both program requirements and flexibilities that lead agencies may opt to use to meet their specific program goals. The final rule also includes federal recommendations to inform state program design and operations. Within broad federal guidelines, lead agencies have considerable discretion to structure their CCDF programs in ways that align with state priorities and family and community needs. To apply for continued federal funding, lead agencies must submit a triennial CCDF Plan to the federal Office of Child Care that describes how their program is meeting regulatory provisions and how it will direct CCDF funds for the next three years.

In this series, we draw on lead agency CCDF Plans for fiscal years (FYs) 2025-2027 to describe the extent to which various strategies—both required and optional—are in effect in Puerto Rico and across 15 states with large populations of Hispanic children eligible for child care subsidies (“Hispanic-populous states”): Arizona, California, Colorado, Florida, Georgia, Illinois, Massachusetts, Nevada, New Jersey, New Mexico, New York, North Carolina, Pennsylvania, Texas, and Washington. Across the series, we focus on subsets of policies and practices with potential relevance for Hispanic families’ child care access, several of which reflect requirements or flexibilities newly established in the 2024 Final Rule. In addition to the current summary of state/territory policy strategies related to the application process, we have conducted similar policy scans related to eligibility practices and family co-payments and care affordability.

Findings

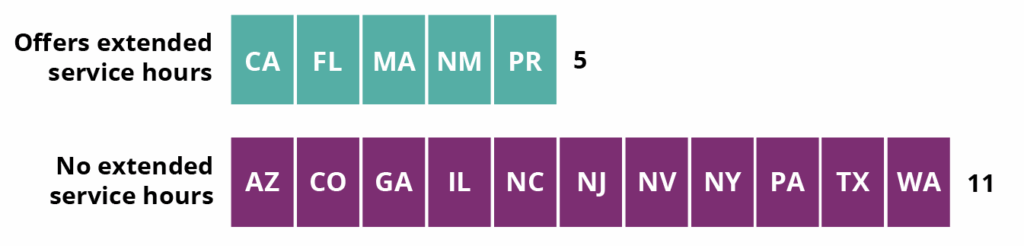

Among Hispanic-populous states, just over one in four (5 of 16) offer extended subsidy office service hours. This suggests that, in most states included in this scan, families can only visit subsidy offices or engage with agency staff during regular weekday business hours, which may conflict with parents’ work schedules. Limited service hours may constrain some families’ ability to successfully navigate and complete the application process.

Figure 1. Less than half of Hispanic-populous states offer evening and/or weekend subsidy office service hours.

States categorized by whether they offer evening and/or weekend service hours

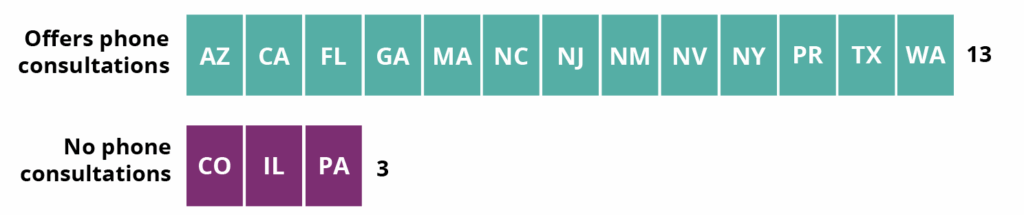

Of the 16 Hispanic-populous states, most (13) offer phone consultations with staff. Having staff available to answer families’ questions about program eligibility criteria and application requirements can facilitate the enrollment process and may reduce the time families need to visit the program office or submit materials for incomplete applications.

Figure 2. Most Hispanic-populous states offer phone consultations.

States categorized by whether they offer phone consultations

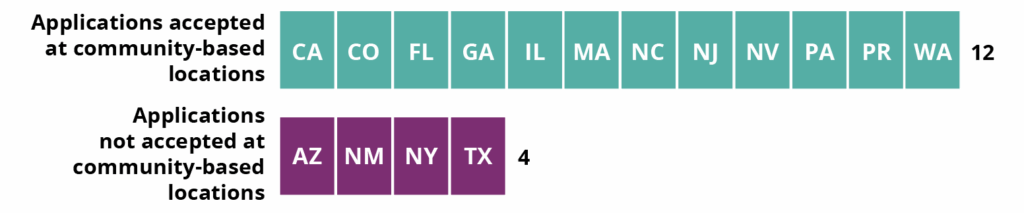

Among Hispanic-populous states, many (12 of 16) also allow applications to be submitted at community-based locations. While lead agencies are not asked directly to report all ways in which families may submit a subsidy application, they are asked about whether they accept applications at community-based locations (e.g., a local Child Care Resource and Referral agency) as part of their outreach strategy. We find that many Hispanic-populous states/territories implement this practice, which may offer families convenience and facilitate the enrollment process.

Figure 3. Many Hispanic-populous states accept applications at community-based locations.

States categorized by whether they accept applications at community-based locations

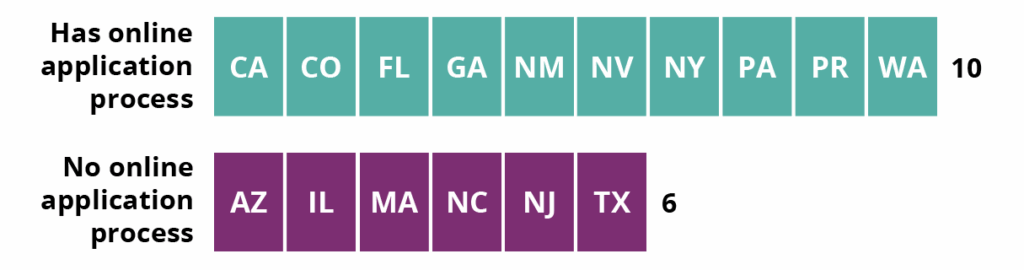

More than half of Hispanic-populous states (10 of 16) have an online application process. Online application portals can offer working parents valuable flexibility and convenience, potentially eliminating the time and travel needed to complete paperwork during an in-person office visit. Many of the states included in this scan report having an online application process, but it is unclear from the information reported in the FY 2025-2027 CCDF plans whether applications can also be submitted in-person. This may be an important option for families with limited access to or comfort with technology.

Figure 4. More than half of Hispanic-populous states have an online application process.

States by whether they have an online application process

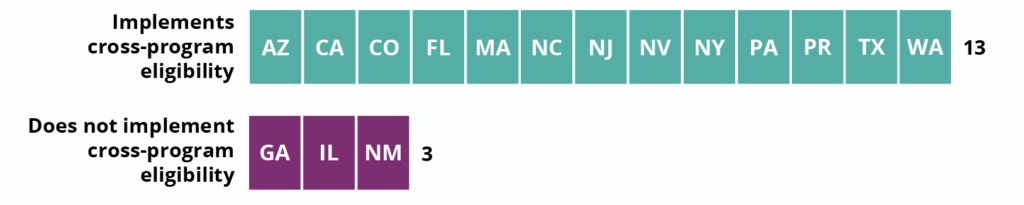

Most Hispanic-populous states (13 of 16) leverage family enrollment in other public assistance programs to determine subsidy eligibility. This practice of cross-program eligibility can streamline and expedite subsidy enrollment and facilitate more coordinated and comprehensive supports for families. Lead agencies vary widely in how—and for which programs—they implement this practice, as further detailed in their CCDF plans.

Figure 5. Many Hispanic-populous states leverage cross-program eligibility.

States categorized by use of cross-program eligibility

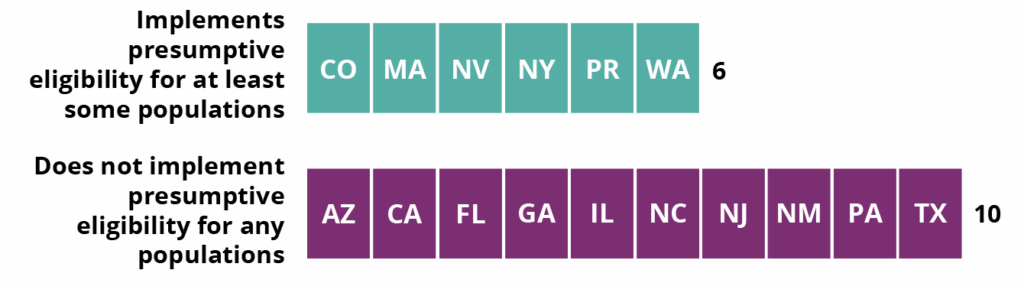

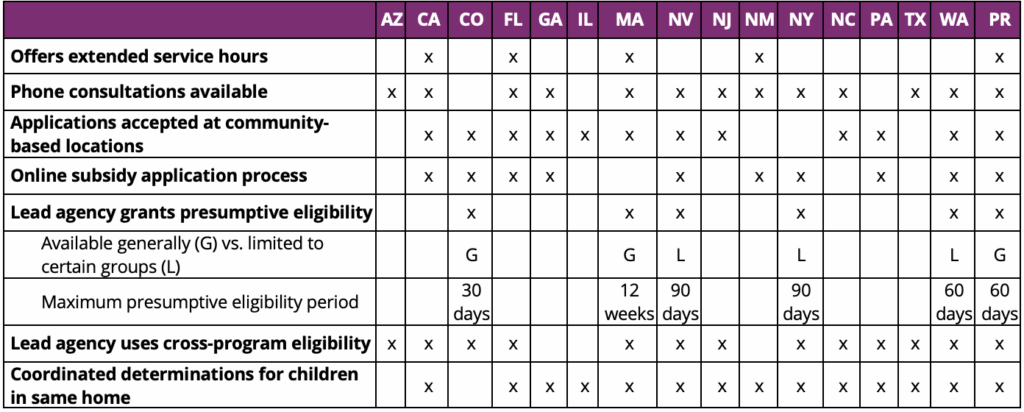

Less than half of Hispanic-populous states (6 of 16) choose to implement presumptive eligibility, wherein families may begin receiving subsidies while their eligibility verification is finalized. Three of the lead agencies that allow presumptive eligibility (Colorado, Massachusetts, Puerto Rico) implement it generally, while the other three (Nevada, New York, Washington) offer it for certain priority populations only (see Appendix Table 1). For example, New York grants presumptive eligibility only to households experiencing homelessness. In the other two states, presumptive eligibility applies to households experiencing homelessness, as well as to families involved with child protective services or foster care (Nevada) and families with new employment (Washington). Across the six states that allow it, provisional eligibility periods range from 30 to 90 days.

Figure 6. Fewer than half of Hispanic-populous states implement presumptive eligibility.

States by whether they implement presumptive eligibility

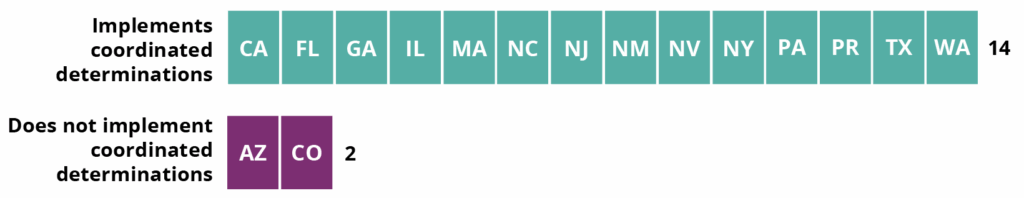

Finally, among Hispanic-populous states, most (14 of 16) coordinate eligibility determinations for children living in the same household. When households include multiple children who are potentially eligible for child care subsidies, coordinating their eligibility determinations and aligning eligibility periods can significantly streamline both initial enrollment and redetermination processes. Most Hispanic-populous states use this practice, which can help minimize disruptions to parents’ employment, education or training activities.

Figure 7. Most Hispanic-populous states coordinate eligibility determinations for children in the same household.

States by whether they coordinate eligibility determinations for children in the same household

Summary and Implications

Policies and practices that help eligible families successfully navigate and complete the child care subsidy application process without undue burden and delay can deliver timely support for working parents’ access to the child care services they need to maintain employment without disruption. Consistent with this, current federal CCDF regulations require state, territorial, and Tribal lead agencies to implement strategies that minimize disruptions to employment, education, and training—activities that support families’ economic self-sufficiency and mobility (CCDBG Reauthorization Act of 2014).

In this policy scan, we examine which policies and practices to streamline the application process Hispanic-populous states have adopted, as described in their triennial CCDF plans covering FYs 2025-2027. We focused our scan on Puerto Rico and the 15 states in which more than 80 percent of Hispanic children in U.S. households with low incomes live, a population that tends to be overrepresented among those eligible for child care subsidies but underrepresented among those served by the program.6

Like other parents employed in the low-wage workforce, many Hispanic parents work in jobs characterized by nonstandard and unpredictable work hours,7 which can create challenges for securing child care arrangements and applying for subsidies. Flexible subsidy program services that can accommodate parents’ schedules can be helpful, as are services that do not require significant time away from work or travel to agency offices. At the same time, it is important that programs offer a range of ways that families can engage with staff and complete the application process. For example, while technology can be used to streamline and automate the application and enrollment process—a possible motivation for the many lead agencies that have implemented an online application process—some families may be more effectively served by in-person services for a host of reasons, including technology-related barriers, language and literacy considerations, and the value of staff facilitation for understanding and meeting complex paperwork requirements. Notably, most of the lead agencies included in this scan with an online application process also report that they allow applications to be submitted at community-based locations.

Our scan reveals considerable variation in the number and types of strategies that lead agencies in Hispanic-populous states use to reduce barriers in the subsidy application process. For example, Puerto Rico implements all seven of the strategies reviewed here, while Arizona, Illinois, and Texas implement only two or three. In addition, some lead agencies choose to apply certain strategies, like presumptive eligibility, to select priority populations only, while others report broader implementation. The practical impacts of various strategies to streamline the application and enrollment process for eligible families will depend on the specifics of how they are applied and for whom. Additional research is warranted on how such policies are implemented across state and local programs and in combination with one another.

Methods

The data reported in this brief come from a review of publicly available state and territory CCDF plans for federal fiscal years 2025-2027, submitted to and approved by the federal Office of Child Care with the Administration of Children and Families, U.S. Department of Health and Human Services. Every three years, to apply for federal funds, state, territory, and Tribal grantees submit a CCDF Plan that describes—and provides assurances for—how the lead agency will administer its child care program in alignment with federal regulations. We focused our analysis on Puerto Rico and 15 states with large populations (i.e., greater than 100,000) of Hispanic children who live in households with low incomes (i.e., below 200% of the federal poverty level) as a key population to be served by the federal child care subsidy program.8

The subset of CCDF application policies and practices summarized in this analysis were selected because of potential relevance for Hispanic families’ access to and utilization of child care subsidies. As noted above, the policy strategies reviewed here may be used by states to reduce barriers in the application and enrollment process, thereby making it easier for eligible working families, including Hispanic families, to access child care assistance. In this analysis, we identify lead agencies as using a particular policy strategy only if they reported it as an element of their program effective FYs 2025-2027 (October 1, 2024 – September 20, 2027). The data presented in this brief do not capture any policy or legislative changes that occurred after approved state/territory CCDF Plans were posted on the ACF website in January 2025. More detailed and up-to-date information about the implementation of state/territory CCDF programs can typically be found in lead agency caseworker manuals and are tracked on an annual basis in the CCDF Policies Database.

Footnote

a Tribal lead agencies also administer CCDF programs and are subject to some of the same federal regulations, while also having unique considerations. Given our focus on states and territories with large populations of subsidy-eligible Hispanic children, we do not include Tribal CCDF programs in this policy scan.

Suggested Citation

Crosby, D.A., Jacome Ceron, A., Wrather, A., Mendez, J., & Omondi, F. (2025). Subsidy application policies to support working families vary across Hispanic-populous states. National Research Center on Hispanic Children & Families. DOI: 10.59377/506z7640f

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to thank the Steering Committee of the National Research Center on Hispanic Children & Families—along with Kristen Harper and Laura Ramirez—for their helpful comments, edits, and research assistance at multiple stages of this project. The Center’s Steering Committee is made up of the Center investigators—Drs. Natasha Cabrera (University of Maryland, Co-PI), Danielle Crosby (University of North Carolina at Greensboro, Co-PI), Lisa Gennetian (Duke University; Co-PI), Lina Guzman (Child Trends, PI), Doré LaForett (Child Trends, Co-I), Julie Mendez (University of North Carolina at Greensboro, Co-PI), and Maria Ramos-Olazagasti (Child Trends, Deputy Director and Co-PI)—and federal project officers Drs. Jenessa Malin and Kimberly Clum (Office of Planning, Research and Evaluation).

This product is supported by Grant Number 90PH0032 from the Office of Planning, Research & Evaluation within the Administration for Children and Families, a division of the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services totaling $7.84 million with 99 percentage funded by ACF/HHS and 1 percentage funded by non-government sources. Neither the Administration for Children and Families nor any of its components operate, control, are responsible for, or necessarily endorse this product. The opinions, findings, conclusions, and recommendations expressed are those of the author(s) and do not necessarily reflect the views of the Administration for Children and Families and the Office of Planning, Research & Evaluation. For more information, please visit the ACF website, Administrative and National Policy Requirement.

Editor: Brent Franklin

Designers: Catherine Nichols and Joseph Boven

About the Authors

Danielle A. Crosby, PhD, is a co-principal investigator of the National Research Center on Hispanic Children & Families, co-leading the research area on early care and education. She is an associate professor in the Department of Human Development and Family Studies at the University of North Carolina at Greensboro. Her research focuses on understanding how policies and systems shape early education access and quality for young children in low-income families.

Anyela Jacome Ceron, MPS, is a graduate student in a Clinical Psychology program at the University of North Carolina at Greensboro. She received her Master’s degree from the University of Maryland, College Park in Clinical Psychological Science. Her research interests focus on the well-being of children and families and understanding risk and protective factors in the context of culture. She also has interests in family engagement in early care and education programs.

Amy Wrather, MS, is a doctoral student in the Human Development and Family Studies department at the University of North Carolina at Greensboro. She recently completed her Master’s degree in the same program. Her research interests focus on promoting high-quality learning environments for young children with disabilities across traditional and alternative models of early childhood education.

Julia Mendez, PhD, is a co-principal investigator of the National Research Center on Hispanic Children & Families, co-leading the research area on early care and education. She is a professor in the Department of Psychology at the University of North Carolina at Greensboro. Her research focuses on risk and resilience among low-income and Latino children and families, with an emphasis on parent-child interactions and family engagement in early care and education programs.

Favour Omondi, MS, is a doctoral student in the Human Development and Family Studies department at the University of North Carolina at Greensboro. She recently completed her Master’s degree in the same program. Her research interests focus on the multi-level factors that place young children at risk for maltreatment and the role of protective mechanisms (including access to high-quality early childhood education) in mitigating these risks.

About the Center

The National Research Center on Hispanic Children & Families (Center) conducts research to inform programs and policy to better serve Hispanic children and families with low incomes. Our research focuses on poverty reduction and economic self-sufficiency; child care and early education, including federal programs such as Head Start (HS) and the Child Care and Development Fund (CCDF); and cross-cutting topics that include parenting, family structure, and family dynamics. The Center is led by Child Trends, in partnership with Duke University, University of North Carolina at Greensboro, and University of Maryland, College Park.

Copyright 2025 by the National Research Center on Hispanic Children & Families.

Appendix

Appendix Table 1. Variation in Key CCDF Policies Related to the Application Process Across 16 States/Territories With Large Populations of Hispanic Children

Source: Authors’ review of state and territory Child Care and Development Fund Plans FYs 2025-2027 (and appendices) approved and posted by the Office of Child Care, as of March 2025, https://acf.gov/occ/form/approved-ccdf-plans-fy-2025-2027.

References

1 Office of the Assistant Secretary for Planning and Evaluation, U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, Factsheet: Estimates of Child Care Eligibility and Receipt for Fiscal Year 2021 (Washington, D.C.: Sept. 2024)

2 Crosby, D. A., Mendez, J., Stephens, C., & Adegbesan, I. (2024). Perspectives from local CCDF program staff in four states on improving Latino families’ access to child care subsidies. National Research Center on Hispanic Children & Families. DOI: 10.59377/334p6150d

3 Ramirez, L., Guzman, L., & Alvira-Hammond, M. (2024). Latino children represent at least 1 in 4 kids nationwide, and more than 40 percent in 5 states and Puerto Rico. National Research Center on Hispanic Children & Families. DOI: 10.59377/865v5358m

4 Hill, Z., Gennetian, L. A., & Mendez, J. (2019b). A descriptive profile of state Child Care and Development Fund policies in states with high populations of low-income Hispanic children. Early Childhood Research Quarterly, 47, 111-123. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ecre- sq.2018.10.003

5 Child Care and Development Fund (CCDF) Program, 89 FR 15366 (March 1, 2024). https://www.federalregister.gov/documents/2024/03/01/2024-04139/improving-child-care-access-affordability-and-stability-in-the-child-care-and-development-fund-ccdf

6 Chien, N. (September 2024). Estimates of Child Care Eligibility & Receipt for Fiscal Year 2021. Office of the Assistant Secretary for Planning and Evaluation, U.S. Department of Health and Human Services.

7 Crosby, D.A., & Mendez, J.L. (2017). How Common Are Nonstandard Schedules Among Low-Income Hispanic Parents of Young Children? National Research Center on Hispanic Children and Families. https://www.hispanicresearchcenter.org/research-resources/how-common-are-nonstandard-work-schedules-among-low-income-hispanic-parents-of-young-children/

8 Alvira-Hammond, M. (2024). 2022 American Community Survey (ACS)/Puerto Rican Community Survey (PRCS) 1-Year Estimates. [Unpublished analyses]. IPUMS USA, University of Minnesota. www.ipums.org