Sep 13, 2023

Research Publication

Child Care Subsidy Staff Share Perspectives on Policy Implementation Practices and Effective Outreach with Latino Families in California

Authors:

This brief is part of a research series on Latino families’ access to social assistance that examines how government programs that offer benefits to income-eligible families are structured and the ways they are implemented that shape families’ access and uptake. Here, we use findings from a survey of California subsidy workers to inform federal and state efforts to reduce administrative burden on families and improve the efficiency, equity, and efficacy of service delivery.

Introduction

The federal Child Care and Development Fund (CCDF), administered through individual states, subsidizes access to affordable early care and education (ECE) for families with low incomes. CCDF subsidies can support parents’ ability to work and positively impact their children’s early academic and social development. While many Latinoa families—who tend to have high rates of parental employment but also low levels of income—stand to benefit from these subsidies, they are currently underserved by the CCDF program in most states. Hispanic children make up approximately 35 percent of those eligible for subsidized care nationwide, but just 20 percent of the population served.1 This is because available CCDF funding serves only a fraction (16%) of eligible children2 and because a smaller proportion of eligible Hispanic children receive subsidized care, relative to eligible children from other racial and ethnic backgrounds.1

This brief—as part of a larger multi-state study of CCDF access for Hispanic families3—aims to improve our understanding of families’ access to subsidies in California, including barriers and facilitators. To that end, we report on findings from our survey of California child care subsidy workers in Spring 2022, which asks frontline staffb and supervisors about their implementation practices and experiences, with a focus on their interactions with Hispanic families. Staff reported on multiple aspects of the subsidy application and eligibility determination process that may present access challenges for some families, as well as their agency’s outreach and communication strategies. California is home to the largest number of Latino children living in households with low incomes. As in most other states, however, Latino families in California are underrepresented among those receiving subsidized care despite being overrepresented among groups with high need for access to affordable care.4

Insights from community-level staff who implement subsidized child care and interact with families can help identify barriers and facilitative practices, thereby informing ongoing system work in California and federal and state efforts to reduce administrative burdens and improve the efficiency, equity, and efficacy of government service delivery.

Key Findings

In documenting the perceptions and experiences of local staff who implement subsidized child care in California, this study has identified areas of potential administrative burden for Latino parents seeking child care assistance, especially related to documentation of work hours and pay. Staff reports also highlighted resources and strategies being used to help Hispanic families learn about, apply for, and receive benefits—including considerable cultural and linguistic capacity among agency staff to serve Spanish-speaking applicants and the use of relationship-based methods to connect with Latino families.

Staff perspectives on child care subsidy eligibility and the application process

Most subsidy staff surveyed were in alignment with California state policy about which activities qualify families for child care assistance and the documentation required from applicants, suggesting consistency for families in the information they receive across staff and office. Many staff also identified challenges that families—including Hispanic families—encounter when trying to provide required documentation.

- According to subsidy staff, Latino families commonly apply for subsidized care to support employment, job training, job search, and ESL classes.

- Consistent with state policy, subsidy staff did not routinely ask applicants for documentation that can create administrative burden for some Latino families, such as Social Security numbers or proof of citizenship.

- More than half of responding staff rated verification of work hours and income as challenging for both Hispanic and other applicants.

Staff perspectives and capacity-related issues around language accessibility of services

Many subsidy staff in California reported racial, ethnic, and language backgrounds similar to the families they serve; on average, subsidy staff had several years of experience helping families access subsidized child care. Some staff noted capacity challenges in serving households who speak primarily Indigenous languages.

- Over half of surveyed staff self-identified as Hispanic, Latino, Latina, or Latinx and reported being a native or fluent Spanish speaker. In addition, more than 60 percent of staff reported being the first or second generation of their families to live in the United States, and thus are familiar with the immigrant experience.

- A majority of local subsidy staff described program materials and interpreter/ translation services as very accessible to families in Spanish, but much less accessible in Indigenous languages from Latin America. For example, only 12 percent of staff described on-site and/or phone translation or interpreter services in Indigenous languages as very accessible to families.

- Although 3 in 4 subsidy staff (68.9%) reported feeling well prepared to help Spanish-speaking families apply for child care assistance, only 18 percent felt at least moderately prepared to help families who speak an Indigenous language.

Staff perspectives on outreach to Latino communities

Many local California subsidy staff shared that they or their agency engage in various types of outreach activities and relationship-based methods to help connect Latine families with child care subsidies and other social services—for example, some staff use community contacts and partnerships with local organizations, such as health providers and pediatrician offices, religious groups, school districts, and community agencies serving Latine families.

- More than 60 percent of those surveyed reported having a community partnership to help them connect Latine families to subsidies and 70 percent reported having a community partnership to help them connect Hispanic families to other services.

- In reporting on how families learn about subsidized child care, most staff (80%) believed word-of-mouth to be effective for Latine applicants. More than half also identified outreach, referrals, and family-initiated phone calls as important information sources for Latino families seeking child care; technology-based sources, such as websites and social media, were rated as less commonly used by Latinx applicants.

Recommendations for reducing subsidy access barriers

The results of this study suggest several policy and practice actions that could reduce access barriers for Hispanic families who are eligible for subsidized child care:

- Employment and income verification/documentation that better reflects the range of parents’ work conditions (including irregular schedules, multiple jobs, and undocumented pay) would reduce administrative burdens for many families with low incomes, including Hispanic families.

- Guidance and training for subsidy workers can clarify eligibility and documentation requirements and help these staff communicate requirements to potential applicants. For example, although driver’s licenses are not required documentation in California, more than half of the responding staff reported that they collect or request them from applicants.

- A diverse social service workforce, with staff who reflect the cultural and linguistic backgrounds of Hispanic families, can be an important resource in promoting greater access to CCDF funding. In California, for example, a potential area for capacity building is communication with Latino families who speak Indigenous languages.

- Strategic partnerships with community organizations may be effective for subsidy offices to connect with Hispanic families and share relevant program information.

California: A Long Established, Diverse, and Changing Hispanic Population State

As the most populous state in the nation, California is also home to the largest number of Hispanic children (4.7 million), who represent 52 percent of the state’s child population.i And this segment of the population is growing: From 2010 to 2020, the number of Hispanic children in the state increased by approximately 15.4 percent, while the non-Hispanic child population decreased by about 7.2 percent.9

A key characteristic of the state’s Latino population is its tremendous diversity and various ancestry groups, including residents tracing their origins to Mexico (83% of all Hispanics in California), El Salvador (5%), Guatemala (3%), South America (2%), and Puerto Rico (1%).10 Two thirds of Hispanic Californians were born in the United States and more than 40 percent of those born outside the United States are citizens, for an overall citizenship rate of more than 80 percent.11 Latino families in California are also linguistically diverse. Roughly 60 percent of young children in the state are Dual Language Learners (DLL), meaning they live in a home where a language other than English is spoken.12 While Spanish is the second most common language to English spoken in the state, a variety of other languages and dialects are spoken within the broader Latino population, including a variety of Indigenous languages from Latin America. Although national and state-level estimates of Indigenous populations and languages are widely unavailable, one study of migrant agricultural workers in rural California in the late 2000s estimated that nearly 30 percent were from Indigenous Mexican communities and spoke 23 different Indigenous languages (with Mixteco, Zapoteco, and Triqui predominant).13 Additionally, a community-based survey of undocumented Indigenous individuals living in Los Angeles during the COVID-19 pandemic included nearly 11,000 people who spoke 17 Indigenous languages from Mexico and Central America.14

Latino individuals make up 38 percent of California’s workforce and are disproportionately represented among workers with low wages.15 For example, the percentage of Latina women in jobs paying less than two thirds of the overall state median hourly wage (28.1%) is roughly twice as high as among White (13.2%), Asian (15.4%) and Black women (15.2%).16 Thus, although Latinos in California have higher incomes and lower poverty rates, on average, than Latino people in other states and territories, they are more likely to experience poverty than individuals from other racial and ethnic groups in California.10 More than two thirds (68%) of Latino children younger than age 13 in the state are eligible for child care subsidies based on federal household income guidelines.1

California’s Subsidized Child Care and Development System

To help families gain affordable access to a range of care and education settings that can support parents’ work and children’s development, California relies on a complex mixed delivery system that combines federal CCDF dollars with several streams of state funding to subsidize the costs of care for children from birth through age 12 through a variety of subsidized child care programs (see below). Across these various programs, eligible families may receive financial assistance through a child care voucher that is used to pay a provider of their choice, or they may be offered a subsidized slot in a state-contracted child care center or family child care home.

California delivers subsidized child care through a variety of programs

- CalWORKs Stages 1-3: Provides child care vouchers to families with low incomes who currently receive (or are transitioning from) cash assistance; served approximately 178,000 children in FY 2020-21

- Alternative Payment Program: Provides child care vouchers to families earning less than 85 percent of the state median income; served approximately 75,000 children in FY 2020-21

- California State Preschool Program: Funds subsidized slots in centers serving children ages 3 and 4 who meet Title 5 requirements; served approximately 143,000 children in FY 2020-21

- General Child Care Program (GCC): Funds subsidized slots in centers and family child care home networks meeting Title 5 requirements; served approximately 32,000 children in FY 2020-21

- Migrant Alternative Payment Program/Migrant Child Care Program: Provides subsidized child care options for families who earn 50 percent or more of their income from agricultural or fishing-related work

While specific eligibility criteria, populations served, and operating guidelines vary across California’s multiple subsidy programs, we describe a few general features of the system (as reported in the state’s CCDF plan for 2022-2024) that are relevant to the findings reported in this brief.17 California’s subsidy system is centralized in that all CCDF program rules and policies are set by the state, except those pertaining to waiting lists, which are managed at the local level. Subsidy implementation and service delivery, however, are decentralized and occur largely at the county level. To administer the various subsidized programs across the state’s 58 counties, the lead agency—the Child Care and Development Division of the California Department of Social Services (DSS)—contracts with numerous local agencies, community-based organizations, and providers; these include county offices of education, county DSS offices, Child Care Resource and Referral offices, contracted child care centers, community-based organizations, school districts, and community college administrative offices. Local partners may administer one or more types of subsidized programs. California families generally qualify for subsidized care by meeting income eligibility guidelines (capped at 85% of state median income) and requirements for parents’ engagement in work, job training, or education activities. Families approved to receive a subsidy may choose any participating licensed or license-exempt child care provider, including center-based care, faith-based programs, and home-based and in-home care. Many families receiving subsidized care in the state are required to pay monthly copayments, which are calculated on a sliding scale and can be as high as 10 percent of annual household income. During the COVID-19 pandemic, parent copayments were waived. In recent years, there have been significant new ECE investments and initiatives in California, but also transitions and new challenges. Pandemic-related, one-time federal relief funds of more than $5 billion dollars increased California’s federal child care dollars more than six-fold from 2019 to 2021.18 Although relief funds have not yet been fully allocated,17 funding for subsidized care and development programs in the state budget totaled $6.9 billion in 2021-2022 and more than 400,000 children were served.19 Despite increased public investments, several datapoints suggest high levels of unmet need for subsidized care in California. Of the state’s more than 2.8 million children younger than age 6, it is estimated that 30 percent are eligible to receive subsidized child care, yet only 8.5 percent are served.20 In addition, 60 percent of the state’s population lives in a “child care desert” with insufficient ECE supply to meet need.21While Latino children are the largest racial/ethnic group served within the state’s subsidized child care program numerically, they are disproportionately underserved relative to their non-Hispanic Black and White peers. Estimates indicate that only 6 percent of state-eligible Hispanic children received CCDF subsidies compared to 19 percent of eligible Black children and 9 percent of eligible White children.22

Staff Perspectives on Child Care Subsidy Eligibility and the Application Process

Qualifying activities for child care subsidy eligibility

One state-level policy choice with implications for subsidy access is the choice of which types of parent/guardian activities or family circumstances can qualify a household for child care assistance. In most states, there are multiple pathways or entry points by which families might be connected to subsidized care. Some families will qualify for this benefit based on parents’ activities to support family well-being, such as employment, training, or job searches. Child care subsidies may also be provided for more child-focused reasons to provide direct support to children experiencing challenging environment circumstances, such as involvement with protective services. In California, each activity and circumstance listed in Figure 1 is considered an eligible qualifying activity for subsidized child care,c with the exception of employment and training activities linked to the Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program (SNAP).23 At the implementation level, local staff perceptions and understanding of state policy can further shape families’ access.

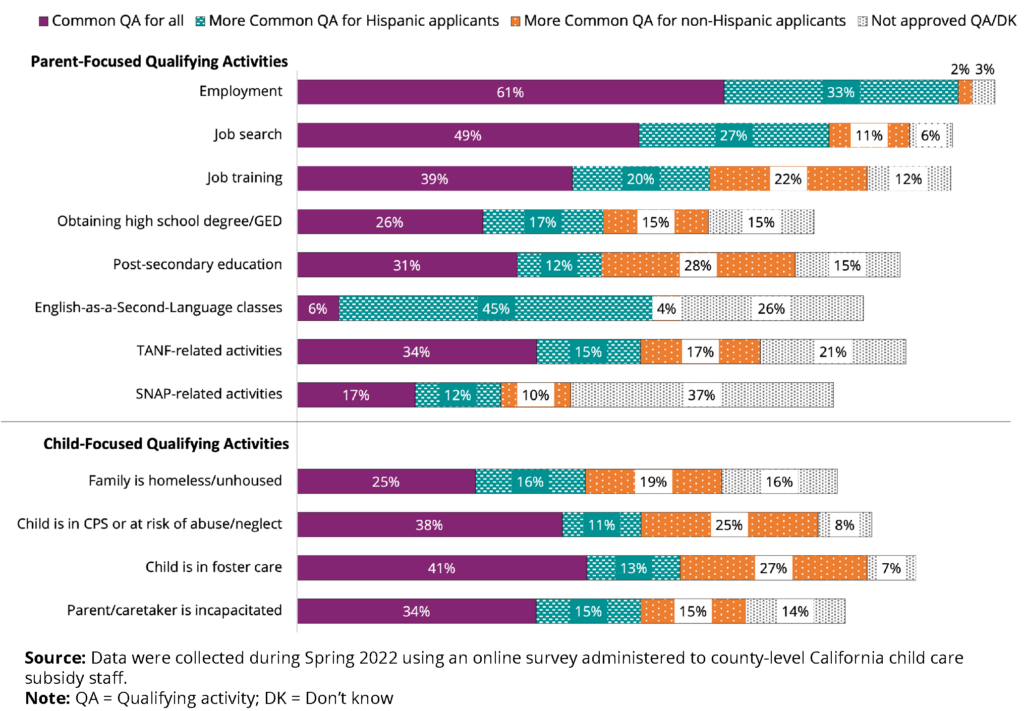

In our survey, California staff reported on which activities they considered to be eligible for subsidized care, as well as those they perceived as common eligibility activities for applicants—both Hispanic and non-Hispanic. In these data, reported in Figure 1, we find that:

- Local subsidy staff generally agreed about which activities are considered qualifying, and their reports largely aligned with California state policy. The highest levels of uncertainty or disagreement were for English as Second Language (ESL) classes and activities related to TANF income assistance; more than 1 in 5 staff did not know or did not consider these to eligible activities. Additionally, nearly 40 percent of staff identified SNAP-related activities as qualifying even though they are not, according to state policy.

- According to staff, the most common qualifying activities for California families receiving subsidized child care are employment, job searches, and children in foster care; however, staff identified a wide range of other qualifying activities among families they serve.

- Qualifying activities reported by staff as relatively more common for Latino families were employment, job searches, and ESL classes. Activities and circumstances reported as relatively more common for non-Latine families were post-secondary education, housing search, involvement with protective services or foster care, or parent/guardian incapacitation.

Figure 1. According to subsidy staff, employment and employment-related activities are common qualifying activities for all applicants, including Hispanic applicants

Percentage of staff who report that each parent- and child-focused activity qualifies families for subsidies, and staff perceptions of how common these activities are among Hispanic and non-Hispanic applicants, 2022

Documents collected as part of the application process

As part of the application process for subsidized child care, staff may request various documents to verify families’ eligibility for the program. Across different states, these requirements can be burdensome or streamlined, depending upon how difficult it is for families to collect and submit documentation.3 Our survey revealed wide agreement among local California subsidy staff about what information is collected as part of the application process and which documentation is challenging for families to provide.

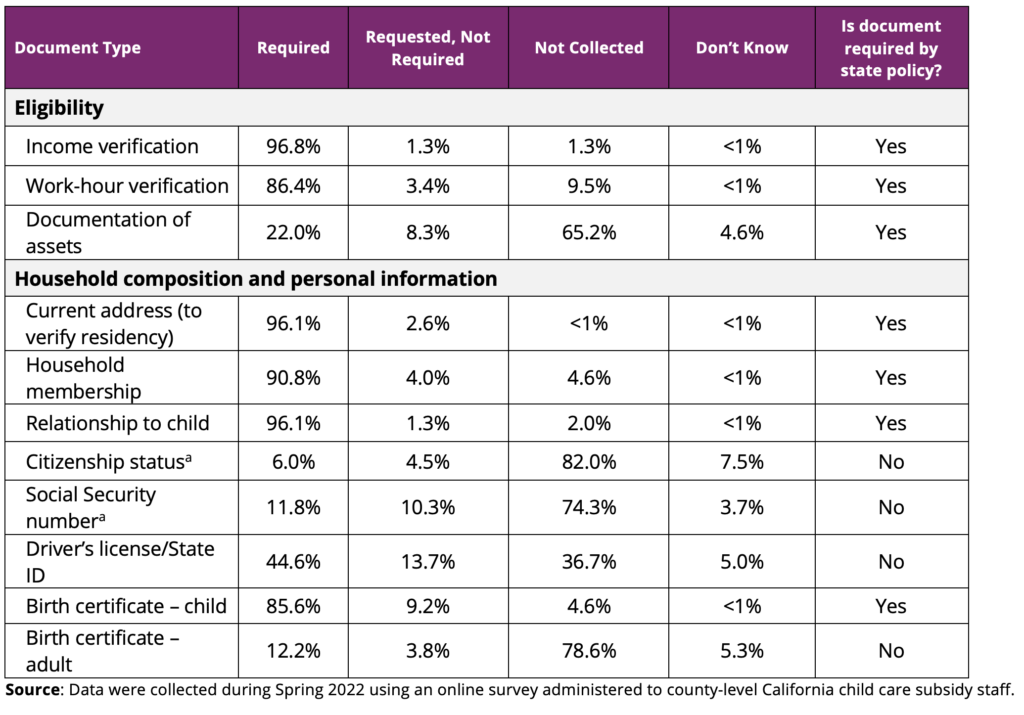

Types of documentation collected from families

- As shown in Table 1, local subsidy workers generally agreed on the types of documents families must provide to apply. Most staff reported collecting documentation related to income and work hour verification, household address and membership, parent/guardian relationship to child, and child birth certificates.

- Most subsidy staff reported that they do not collect additional documents, such as citizenship status documentation, Social Security numbers, or adult birth certificates.

- There was less consistency in staff responses about whether families are required to provide a valid driver’s license/state ID and documentation of assets.

Table 1. Documents collected during application process according to local subsidy staff, and whether documents are required by state policy, 2022

Staff reports of documentation challenges

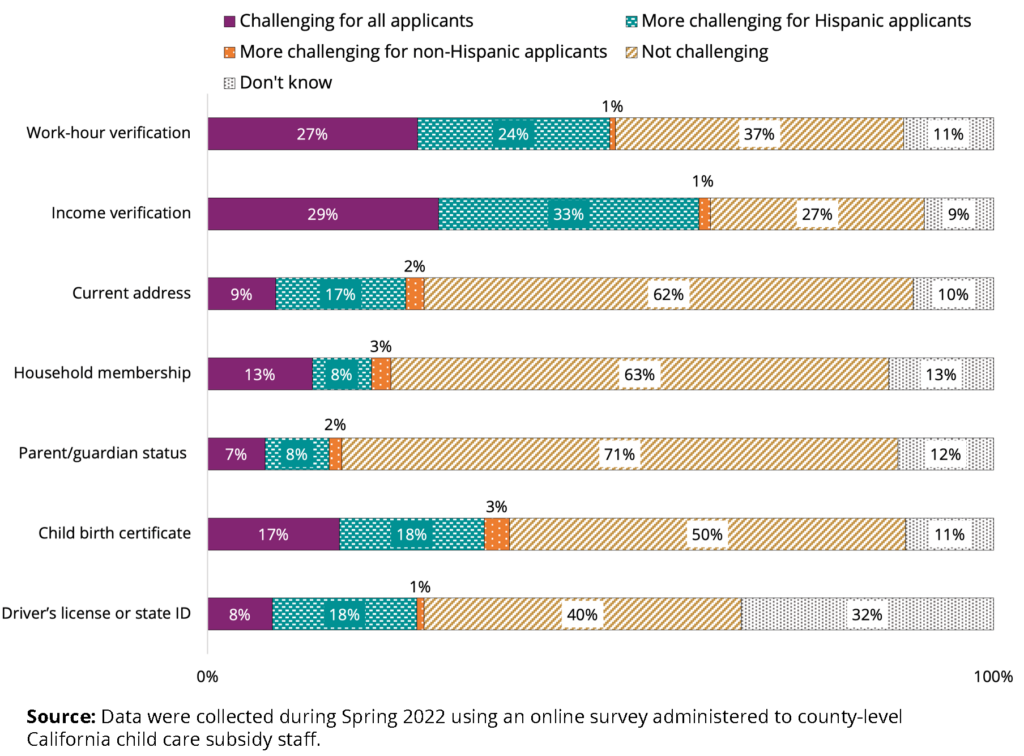

- Many local subsidy staff did not perceive any challenges for families in providing documents required to apply for subsidies, although this varied by type of documentation (Figure 2). However, when staff did report challenges, they generally felt that these challenges particularly impacted Latinx applicants.

- Documents related to income and work-hour verification were the most likely to be reported by staff as difficult for families—and especially Hispanic families—to provide. More than half of the responding staff identified these as challenges.

Figure 2. More than half of staff report that work-hour and income verification documents are challenging for families to provide, and relatively more challenging for Latine than non-Latine families

Percentage of subsidy staff who report that application documents are challenging to collect, 2022

Staff perceptions of why documents are challenging for families to provide

Many surveyed subsidy staff (more than 100 respondents, 59% of the full sample) provided open-ended descriptions of the challenges they perceived—or had experienced—related to collecting documentation from families. The sample survey respondent quotes provided below illustrate how providing work and income verification can create stress and potential hurdles to families when they apply for CCDF subsidies. The challenge of collecting and keeping documents from multiple jobs, especially informal and irregular job arrangements, is evident. Research has shown that non-standard, irregular hours are particularly common among low-income Latine workers. 24

“Parents who work irregular hours, whose employment is informal, or who work multiple jobs may struggle to provide work-hour verification.”

“Our program collects 12 months’ worth of income verification documents, due to serving seasonal migrant workers and this is very challenging as they move around and often [lose] documents and work for multiple companies or independent contractors.”

“Documents are most challenging for self-employed families to show need and income regardless of their background. Employees that have varying schedule[s] can be difficult to provide documentation for as well as income for employees that are not on an official payroll.”

“Many times our Latino/a/x families are working for cash and are concerned to ask their employer for documentation of income or hours worked. Even families that are paid checks are [leery] to provide this information.”

Staff Perspectives on Communication and Outreach Efforts

Language accessibility of program information and resources

Approximately 1 in 4 U.S. Hispanic children in families with low incomes live in a household in which no adult is proficient in English.25 These families may experience greater administrative burden and learning costs associated with accessing child care assistance.6 Providing program information in Spanish and Indigenous languages as part of a state’s broader CCDF consumer education efforts—and having staff or interpreter/translation services available—can be important tools for facilitating subsidy access among linguistically diverse households.

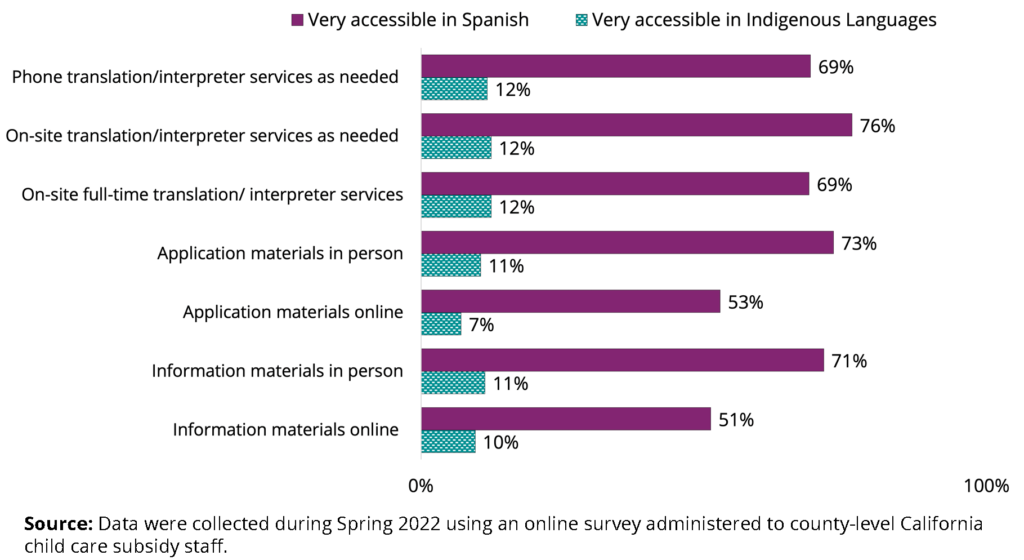

California’s child care subsidy staff responded to multiple questions about the language accessibility of program materials and services, and about their personal capacity to communicate with families who speak Spanish and Indigenous languages. Among the findings shown in Figure 3, we find that:

- More than half of the surveyed local staff felt that informational and application materials are very accessible online in Spanish, and nearly three quarters perceived Spanish-language materials to be very accessible in person.

- Most staff also felt that Spanish-language translation or interpretation services are very accessible when needed, both on-site or by phone.

- Only 12 percent of local staff felt that on-site and phone translation/interpreter services are very accessible to help them serve Indigenous-language-speaking families, with 69 percent reporting these services are barely or not accessible at all.

Figure 3. Most staff viewed program materials and services as very accessible in Spanish but not accessible in Indigenous languages

Percentage of staff reporting program materials and services are very accessible in Spanish and Indigenous Latin American languages, 2022

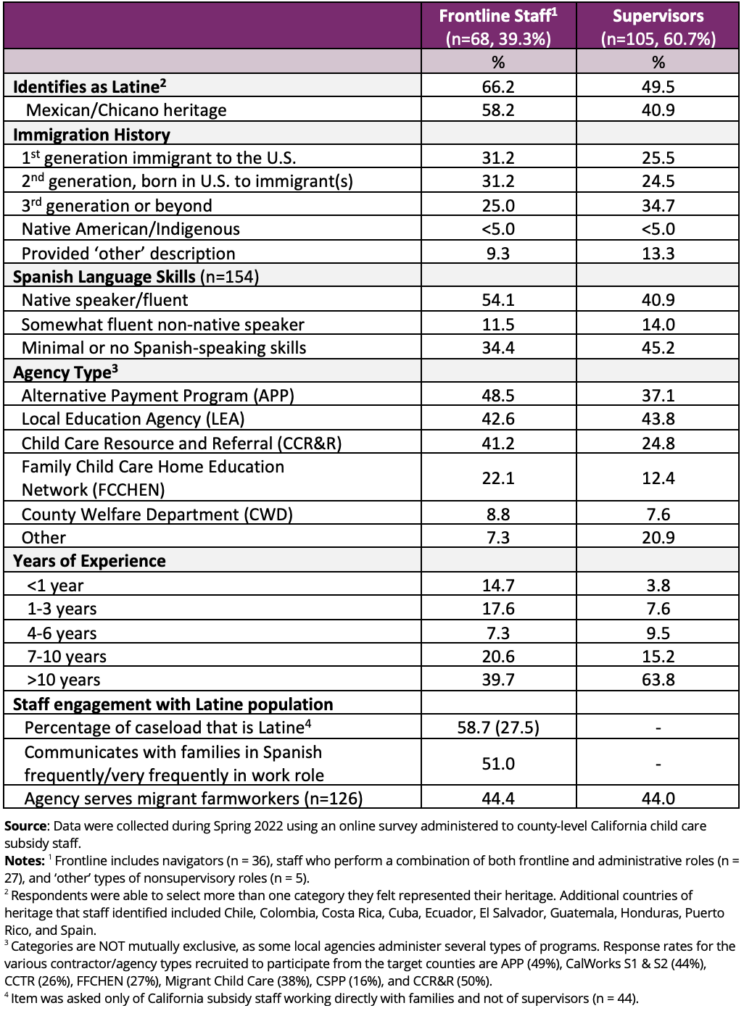

Similarly, many staff have the cultural and linguistic capacity to engage with Spanish-speaking families but appear to be more limited in their ability to communicate with families who speak Indigenous languages (see Table 3).

- Roughly two thirds of staff self-identified as Hispanic, Latino, or Latinx (66%) and a majority of those reported being of Mexican/Chicano heritage.

- Notably, more than half of responding staff described themselves as having native or fluent Spanish-speaking skills, suggesting that many California subsidy staff have personal capacity to support Spanish-speaking Latine families. Indeed, 51 percent reported that they communicate with families in Spanish frequently or very frequently in their work role.

- In contrast, while more than half say they engage with families who need translation or interpreter services in an Indigenous language, most staff do not describe this as a frequent occurrence and very few reported speaking an Indigenous language themselves.

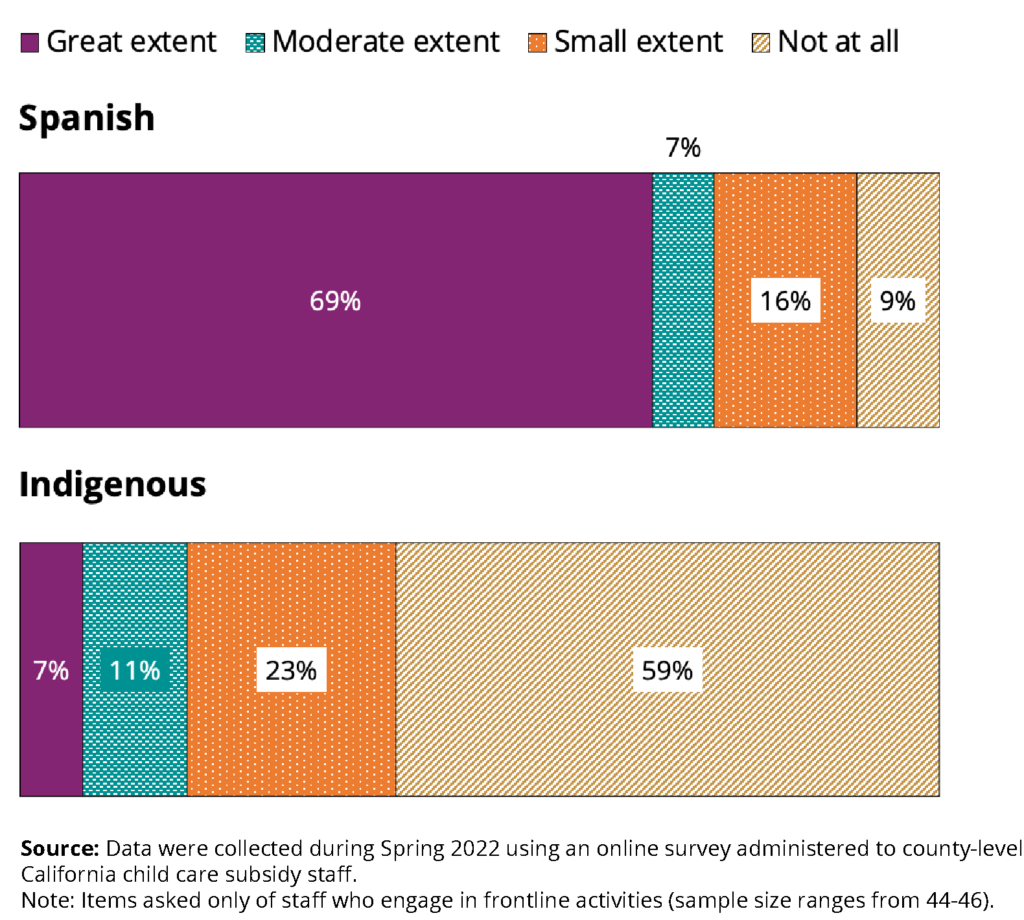

This divergence in language accessibility of program materials and services for Latine families who primarily speak Spanish and those who primarily speak an Indigenous language is mirrored in staff reports of the degree to which they are prepared to serve families with these different communication needs (Figure 4).

- The majority of staff (68.9%) reported feeling prepared to a great extent to serve Spanish-speaking families, with only a small percentage (8.9%) saying they feel not at all Additionally, nearly 85 percent of staff report that there are dedicated staff in their office who work with Spanish-speaking families (data not shown).

- In contrast, the majority of staff (59.1%) felt not at all prepared to serve families who need communications in an Indigenous language, with only a small percentage (6.8%) saying they feel prepared to a great extent to serve these families.

Figure 4. A majority of local subsidy staff feel well-prepared to help Spanish-speaking families, but less feel this way for families who speak an Indigenous language

Percentage of staff reporting different levels of preparedness to serve families who speak Spanish and families who speak an indigenous language, 2022

Common methods by which Latino families learn about and apply for subsidies

Access to child care subsidies requires that families be aware of the program and application process. Results from a study of White, Black, and Hispanic families with middle to low incomes found that 1 in 5 did not apply for government assistance because they did not know it was possible to receive such assistance, while an additional 10 to 15 percent believed they were ineligible.26 Understanding the most common methods by which Latine families learn about child care subsidy programs can potentially help subsidy offices and workers use these strategies to promote greater ECE access.

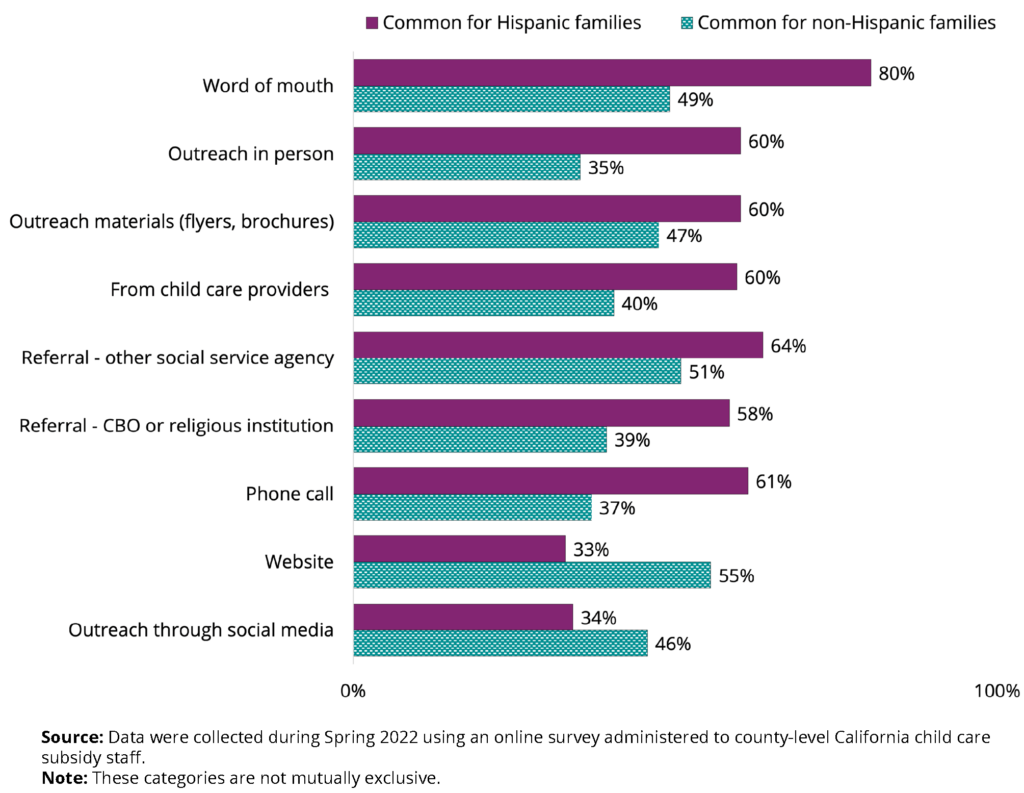

According to local Californian subsidy staff, families learn about the availability of subsidized child care through a variety of methods, with some perceived differences in how Latine and non-Latine families commonly obtain information (Figure 5).

- Staff reported that relationship-based methods—such as word of mouth, in-person meetings, phone calls, and referrals from child care or social service providers and community-based organizations (CBOs)—were relatively more common for Latinx families than for non-Latinx families.

- On the other hand, website materials and social media outreach were reported as relatively more common sources of information about the program for non-Hispanic families, relative to Hispanic families.

Figure 5. Word of mouth and relationships are important outreach practices for Hispanic families

Subsidy staff reports of common ways by which families learn about subsidized child care, 2022

Staff outreach efforts

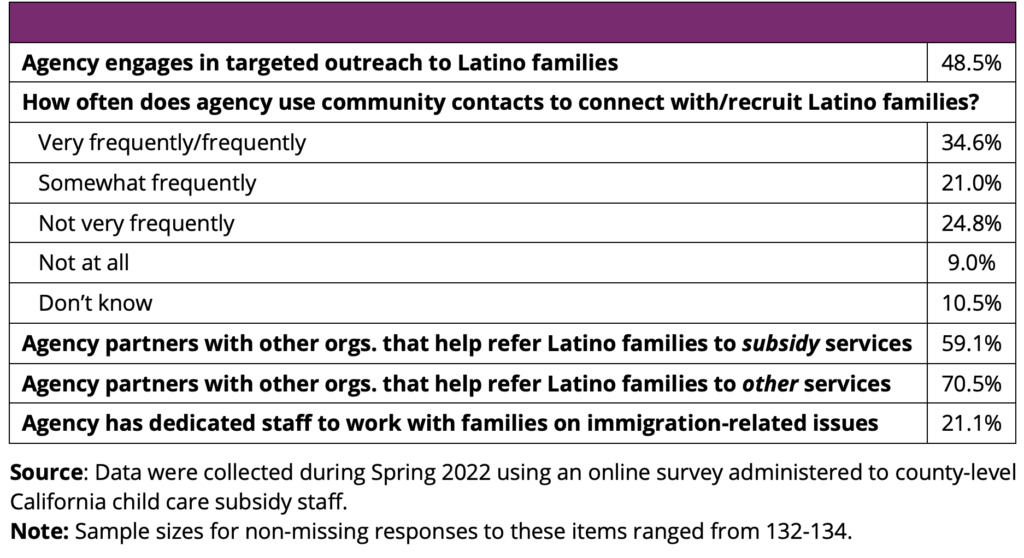

Culturally and linguistically appropriate methods of outreach can be important tools for helping families learn about and access subsidized child care. We asked subsidy workers in California to describe some of their efforts to connect with Latine families and the frequency with which they engaged in these activities. We find that:

- Nearly half of local subsidy staff (48.5%) reported that their agency engaged in outreach targeted for Latinx families, and 1 in 3 staff reported that their agency uses community contacts to connect with Latinx families regularly.

- Many staff also reported that their agency partners with organizations that refer Hispanic families to subsidies (59%) and other social service supports (70%).

- Local organization partner categories mentioned by subsidy staff include health providers and pediatrician offices, religious groups, school districts, and community agencies serving Latine families.

- 1 in 5 staff reported that their subsidy agency has at least one dedicated staff member who works with families on immigration-related issues.

Table 2. Subsidy staff reports of local agency outreach efforts and resources, 2022

Conclusion and Future Directions

Previous research has shown that state CCDF policy choices impact families’ access to subsidized child care, with more restrictive policies being one possible reason that eligible Hispanic children are underserved by the CCDF program in a majority of states.3 Relatively less research has examined the role of local frontline and supervisory staff who help administer the child care subsidy program and whose implementation practices might either facilitate access or exacerbate existing administrative burdens and inequities. To this end, a 2021 executive order from the White House expressed interest in making improvements in “service delivery and customer experience” to reduce administrative burden and the “time tax” on people seeking access to government services.6

As part of a larger effort to understand how social assistance programs are structured and implemented on the ground in ways that may shape Hispanic families’ access, the current study shares the perspectives of local child care subsidy staff in California who reported on their administrative practices and experiences serving Hispanic families. Staff survey responses provided several insights on how Hispanic children may be more equitably served by the CCDF program, both in California and other states. In describing how families apply and qualify for child care assistance, staff reports identified areas that could be addressed to reduce the complexity of the application and certification process, such as simplifying or modifying employment and income documentation requirements to better reflect the realities of many Hispanic workers’ jobs. The data reported here also suggest a need to clarify—through guidance or training for subsidy workers—which documents are required in California, and to share this guidance with potential applicants. Careful communication of the range of activities that qualify for assistance and the documentation used to determine eligibility could help reduce learning costs for families seeking CCDF funding. According to local staff, in-person and relationship-based communication methods may be more helpful for connecting with Hispanic families than online sources of information. To be effective, however, these communications and CCDF consumer education materials must also be provided in the languages that families speak. While the experiences and language skills of responding staff suggest that program resources and interactions are widely available in Spanish (at least in the relatively Hispanic-dense communities we sampled), they also highlight a need to build capacity to serve families who speak Indigenous languages.

The results reported in this brief point to several important directions for future research. A closer investigation of how local-level variation in program implementation, community demographics, and supply and demand of services relate to program uptake among Latinos could provide useful insights. In addition, although CCDF workers reported significant outreach to families, more research is needed to explore how families receive these communications, and how the characteristics of workers (e.g., their gender, race, experiences, etc.) may also be important factors in uptake of programs. Specifically, how does word of mouth help families apply for or pursue subsidies and to what extent does knowledge of the subsidy program that is shared within communities reflect up-to-date policy and program information? Also, from families’ perspectives, what obstacles to being served by the program do they experience? Answering these questions can help ensure that CCDF funds have the widest reach and impact and that they equitably serve eligible families, in California and in other states.

Methodology and Study Design

For our multi-state study of how state and local CCDF implementation may impact Hispanic families’ access to subsidized child care, the research team developed an online survey for community-level staff who help administer the program. For each state participating in the larger study, we tailored the survey to reflect the state context based on conversations with the state lead CCDF agency. In California, leadership at the Child Care and Development Division at California Department of Social Services provided input and helped facilitate distribution of the survey to county-level frontline caseworkers (often referred to as navigators in the California system) and administrators completed via a hyperlink to the REDCapd platform;27 the survey was available from May to August 2022. Through a series of closed- and open-ended items, subsidy staff were asked about their practices and experiences helping families apply for child care subsidies (currently and during the COVID-19 pandemic), as well as their perceptions of challenges, opportunities, and strategies for engaging Hispanic families who might benefit from child care assistance. Survey respondents answered largely the same survey items, with a few subsets of questions asked only of frontline staff (i.e., caseload characteristics) and administrative staff (i.e., agency operations). The survey was comprised of multiple sections that covered the following areas: staff and agency characteristics, the subsidy eligibility and application process, outreach to Hispanic communities, language accessibility, impacts of the COVID-19 pandemic on CCDF services, perceived barriers to subsidized child care, and recommendations for improving services.

Sample and recruitment. In California, subsidies are administered through multiple programs and types of agencies, including social services, alternative payment programs, private and public pre-K providers, child care resource and referral offices, and county-level departments of education. Although the state of California has a total of 58 counties, this study targeted a subset of 31 counties based on criteria that include the prevalence of poverty among families with young children, Hispanic population density, and recommendations by state-level administrative staff regarding emerging and unique Hispanic communities.

A total of 173 subsidy workers in 41 (out of 58) counties across California participated in the survey. Subsidy staff participating on this survey represented 28 of the targeted counties, along with 13 additional California counties that were not targeted for this study but likely heard about it during statewide lead agency contractor meetings. Descriptive information about the staff who participated in this study is reported in Table 3. Notably, just over 60 percent of responding staff were in supervisor roles, and many were very experienced and possessed significant language and cultural capacity for serving Latine families.

Table 3. Characteristics of Local California Child Care Subsidy Staff (N =173), 2022

Some limitations and caveats are important to recognize with this initial descriptive study. First, our recruitment strategy of sending the study invitation to a key contact person in each local office for distribution to eligible staff yielded a higher proportion of supervisors in the final sample of respondents than frontline staff. Given that supervisory staff may have more frequent communication with the state-level administering agency, this may have contributed to the high levels of consistency between staff reports and documented state policy. Data from frontline staff who work directly with families may be particularly insightful for understanding implementation practices and staff-family interactions. Our data also represent staff perspectives from the highest-density and highest-poverty areas in California, in which significant populations of Latine children reside; we did not recruit from every county and our sample of respondents is not representative of the state’s subsidy workforce.

Some limitations and caveats are important to recognize with this initial descriptive study. First, our recruitment strategy of sending the study invitation to a key contact person in each local office for distribution to eligible staff yielded a higher proportion of supervisors in the final sample of respondents than frontline staff. Given that supervisory staff may have more frequent communication with the state-level administering agency, this may have contributed to the high levels of consistency between staff reports and documented state policy. Data from frontline staff who work directly with families may be particularly insightful for understanding implementation practices and staff-family interactions. Our data also represent staff perspectives from the highest-density and highest-poverty areas in California, in which significant populations of Latine children reside; we did not recruit from every county and our sample of respondents is not representative of the state’s subsidy workforce.

About This Series and Brief

This brief is part of a research series on Latino families’ access to social assistance that examines—from different vantage points—the ways in which government programs that offer benefits to income-eligible families are structured and then implemented on the ground in ways that shape families’ access and uptake. We apply a Hispanic lens to this work—analyzing administrative burden with a focus on Hispanic populations and families—to examine how administrative burden might limit the reach of program benefits among Latino families in particular, and to identify policies and practices that can facilitate access.

Previous work on administrative burden—including our own analysis5—suggests that programs like CCDF may be structured or implemented in ways that can exclude eligible individuals from participating by creating learning, psychological, and compliance costs. Learning costs occur when families are unaware of a resource or how to apply. Psychological and compliance costs arise from aspects of the process that create negative experiences for applicants or are too challenging to navigate. Recognizing that such costs limit access and potentially exacerbate inequities, the 2021 White House Executive Order on Transforming Federal Customer Experience and Service Delivery to Rebuild Trust in Government6 directs governmental agencies to assess and improve the customer experience and reduce access barriers to public services, especially for individuals and communities who have been historically underserved.

Research has begun to explore various ways that Latino families with low incomes may encounter administrative burdens when applying to programs like CCDF, including language barriers, challenges providing documentation to determine eligibility, and lack of time or experience to navigate agency procedures.3,7 Local staff tasked with implementing and administering these programs play a key role in this process. As the primary (and potentially sole) point of contact for families seeking assistance, agency staff members’ perceptions, knowledge, and practices shape the degree to which parents can navigate administrative hurdles and take up the benefits for which they are eligible.

Suggested Citation

Crosby, D., Mendez, J., & Stephens, C. (2023). Child Care Subsidy Staff Share Perspectives on Policy Implementation Practices and Effective Outreach with Latino Families in California. National Research Center on Hispanic Children & Families. https://doi.org/10.59377/431x7190r

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to thank the Steering Committee of the National Research Center on Hispanic Children & Families—along with Yoonsook Ha, Kristen Harper, and Laura Ramirez—for their helpful comments, edits, and research assistance at multiple stages of this project. The Center’s Steering Committee is made up of the Center investigators—Drs. Natasha Cabrera (University of Maryland, Co-I), Danielle Crosby (University of North Carolina at Greensboro, Co-I), Lisa Gennetian (Duke University; Co-I), Lina Guzman (Child Trends, PI), Julie Mendez (University of North Carolina at Greensboro, Co-I), and Maria Ramos-Olazagasti (Child Trends, Deputy Director and Building Capacity lead)—and federal project officers Drs. Ann Rivera, Jenessa Malin, and Kimberly Clum (Office of Planning, Research and Evaluation). Finally, we express our appreciation for the California state and local agency partners who helped facilitate the study and the subsidy staff and administrators who were generous with their time and responded to the survey.

Editor: Brent Franklin

Designer: Catherine Nichols

About the Authors

Danielle Crosby, PhD, is a co-investigator of the National Research Center on Hispanic Children & Families, co-leading the research area on early care and education. She is an associate professor in the Department of Human Development and Family Studies at the University of North Carolina at Greensboro. Her research focuses on understanding how policies and systems shape early education access and quality for young children in low-income families.

Julia Mendez, PhD, is a co-investigator of the National Research Center on Hispanic Children & Families, co-leading the research area on early care and education. She is a professor in the Department of Psychology at the University of North Carolina at Greensboro. Her research focuses on risk and resilience among ethnically diverse children and families, with an emphasis on parent-child interactions and family engagement in early care and education programs.

Christina Stephens, PhD, was previously a pre-doctoral fellow with the National Research Center on Hispanic Children & Families, in the research area on early care and education. Christina’s research focuses on understanding the factors and policies that promote child care access and quality, particularly among low-income families with young children. She is now a postdoctoral researcher at the University of Virginia with the Education Science Training Program on English Learners (EL-VEST). A portion of her effort on this project was supported by the Institute of Education Sciences, U.S. Department of Education, through Grant R305B210008 to the University of Virginia. The opinions expressed are those of the authors and do not represent views of the Institute or the U.S. Department of Education.

About the Center

The National Research Center on Hispanic Children & Families (Center) is a hub of research to help programs and policy better serve low-income Hispanics across three priority areas: poverty reduction and economic self-sufficiency, healthy marriage and responsible fatherhood, and early care and education. The Center is led by Child Trends, in partnership with Duke University, University of North Carolina at Greensboro, and University of Maryland, College Park. The Center is supported by grant #90PH0028 from the Office of Planning, Research, and Evaluation within the Administration for Children and Families in the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services.

The National Research Center on Hispanic Children & Families is solely responsible for the contents of this brief, which do not necessarily represent the official views of the Office of Planning, Research, and Evaluation, the Administration for Children and Families, or the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services.

Copyright 2023 by the National Research Center on Hispanic Children & Families.

Footnotes

a We use “Hispanic,” “Latino,” “Latinx,” and “Latine” interchangeably throughout the brief. The terms are used to reflect the U.S. Census definition to include individuals having origins in Mexico, Puerto Rico, and Cuba, as well as other “Hispanic, Latino or Spanish” origins.

b In California, the term “navigator” is used to capture frontline child care subsidy workers who assist families with processing applications for child care subsidies. In this brief, we use subsidy staff or navigator interchangeably.

c As a conceptual framing, we organized qualifying activities by whether they are parent-focused versus child-focused; however, readers, should note that these are not official designations.

d Study data were collected and managed using REDCap electronic data capture tools hosted at University of North Carolina at Greensboro. REDCap (Research Electronic Data Capture) is a secure, web-based software platform designed to support data capture for research studies, providing 1) an intuitive interface for validated data capture; 2) audit trails for tracking data manipulation and export procedures; 3) automated export procedures for seamless data downloads to common statistical packages; and 4) procedures for data integration and interoperability with external sources.

References

1 U.S. Government Accountability Office. (2016). Access to subsidies and strategies to manage demand vary across states (GAO-17-60). https://www.gao.gov/products/GAO-17-60

2 U.S. Government Accountability Office. (2023). Child Care: Subsidy Eligibility and Use in Fiscal Year 2019 and State Program Changes during the Pandemic (GAO-23-106073). https://www.gao.gov/products/GAO-23-106073

3 Lin, Y., Crosby, D., Mendez, J. & Stephens, C. (2022). Child care subsidy staff share perspectives on administrative burden faced by Latino applicants in North Carolina. National Research Center on Hispanic Children & Families. https://www.hispanicresearchcenter.org/wp-content/uploads/2022/08/HC-NC-CCDF-brief_FINAL.pdf

4 Schumacher, K. (2019). Subsidized Child Care Can Help Reduce Barriers to Success. California Budget & Policy Center. https://calbudgetcenter.org/resources/subsidized-child-care-can-help-reduce-barriers-to-success/

5 Hill, Z., Gennetian, L.A., & Mendez, J. (2019). A descriptive profile of state Child Care and Development Fund policies in states with high populations of low-income Hispanic children. Early Childhood Research Quarterly, 47, 111-123. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ecresq.2018.10.003

6 The White House. (2021, December 13). Executive Order on Transforming Federal Customer Experience and Service Delivery to Rebuild Trust in Government. https://www.whitehouse.gov/briefing-room/presidential-actions/2021/12/13/executive-order-on-transforming-federal-customer-experience-and-service-delivery-to-rebuild-trust-in-government/

7 Barnes, C. & Gennetian, L. (2021). Experiences of Hispanic Families with Social Services in the Racially Segregated Southeast: Views from Administrators and Workers in North Carolina. Race and Social Problems, 13(1), 6-21. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12552-021-09318-3

8 U.S. Census Bureau. (2020). American Community Survey. https://www.census.gov/programs-surveys/acs/data/summary-file.html

9 California Department of Finance. (2020). California County Population Estimates and Components of Change by Race/Ethnicity, 2010-2020. https://dof.ca.gov/forecasting/demographics/estimates/estimates-e6-2010-2021/

10 Ahn, T., De Leon, H., Galdámez, M., Oaxaca, A., Perez, R., Ramos-Vega, D., Renteria Salome, L., & Zong, J. (2022). 15 Facts About Latino Well-Being in California. Los Angeles, CA: UCLA Latino Policy and Politics Institute. https://latino.ucla.edu/research/15-facts-latinos-california/

11 Public Policy Institute of California. (2022). California’s Hispanic Community. https://www.ppic.org/blog/californias-hispanic-community/

12 Holtby, S., Lordi, N., Park, R., & Ponce, N. (2017). Families with young children in California: Findings from the California Health Interview Survey, 2011-2014 by geography and home language. UCLA Center for Health Policy Research. https://healthpolicy.ucla.edu/publications/Documents/PDF/2017/Child_PB_FINAL_5-31-17.pdf

13 Mines, R. Nichols, S. & Runsten, D. (2010). California’s Indigenous Farmworkers: Final report of the indigenous farmworker study (IFS) to the California endowment. http://www.indigenousfarmworkers.org/IFS%20Full%20Report%20_Jan2010.pdf

14 Comunidades Indígenas en Liderazgo. (2022). We are Here. CIELO, UCLA AISC, UCLA Promise Institute for Human Rights, UCLA Bunche Center. https://storymaps.arcgis.com/stories/618560a29f2a402faa2f5dd9ded0cc65

15 U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics. (2021). Hispanics or Latinos made up over one-fourth of the labor force in six states in 2020. The Economics Daily. https://www.bls.gov/opub/ted/2021/hispanics-or-latinos-made-up-over-one-fourth-of-the-labor-force-in-six-states-in-2020.htm

16 Schumacher, K. (2017). Subsidized Child Care and Development Programs Vary by Race and Ethnicity. California Budget & Policy Center. https://calbudgetcenter.org/resources/subsidized-child-care-and-development-programs-vary-by-race-and-ethnicity/

17 California Department of Social Services. (2023). Child Care and Development Fund State Plan. https://www.cdss.ca.gov/inforesources/child-care-and-development/fund-state-plan

18 Schumacher, K. (2022). Moving beyond Relief for California Child Care. California Budget & Policy Center. https://calbudgetcenter.org/resources/moving-beyond-relief-for-california-care/

19 Legislative Analyst’s Office. (2021). The 2021-22 Budget: Child Care Proposals. https://lao.ca.gov/reports/2021/4363/Child-Care-Proposals-021121.pdf

20 Center for American Progress (2021). Early Learning Fact Sheet 2021: California. https://www.americanprogress.org/wp-content/uploads/sites/2/2021/12/California.pdf

21 Malik, R., & Hamm, K. (2017). Mapping America’s Child Care Deserts. Center for American Progress. https://www.americanprogress.org/article/mapping-americas-child-care-deserts/

22 Ullrich, R., Schmit, S. & Cosse, R. (2019). Inequitable Access to Child Care Subsidies. CLASP. https://www.clasp.org/sites/default/files/publications/2019/04/2019_inequitableaccess.pdf

23 Minton, Sarah, Kelly Dwyer, and Danielle Kwon (2022). Key Cross-State Variations in CCDF Policies as of October 1, 2020: The CCDF Policies Database Book of Tables. OPRE Report 2022-60, Washington, DC: Office of Planning, Research, and Evaluation, Administration for Children and Families, U.S. Department of Health and Human Services. https://www.acf.hhs.gov/opre/report/key-cross-state-variations-ccdf-policies-october-1-2020-ccdf-policies-database-book

24 Wildsmith, E., Ramos-Olazgasti, M., & Alvira-Hammond, M. (2018). The Job Characteristics of Low-Income Hispanic Parents. National Research Center on Hispanic Children and Families. https://www.hispanicresearchcenter.org/research-resources/the-job-characteristics-of-low-income-hispanic-parents/

25 Wildsmith, E., Alvira-Hammond, M., & Guzman, L. (2016). A National Portrait of Hispanic Children in Need. National Research Center on Hispanic Children and Families. https://www.hispanicresearchcenter.org/wp-content/uploads/2019/08/Hispanics-in-Need-Errata-11.29-V21.pdf

26 Alvira-Hammond, M. & Gennetian, L. (2015). How Hispanic parents perceive their eligibility and need for public assistance. National Research Center on Hispanic Children & Families. https://www.hispanicresearchcenter.org/research-resources/how-hispanic-parents-perceive-their-need-and-eligibility-for-public-assistance/

27 Harris, P. A., Taylor, R., Thielke, R., Payne, J., Gonzalez, N., & Conde, J. G. (2009). Research electronic data capture (REDCap)–a metadata-driven methodology and workflow process for providing translational research informatics support. Journal of biomedical informatics, 42(2), 377–381. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jbi.2008.08.010