Sep 25, 2019

Infographic, Research Publication

How State Policies Might Affect Hispanic Families’ Access to and Use of Child Care and Development Fund Subsidies

Authors:

The Child Care Development Fund (CCDF) is a federal and state partnership that provides child care assistance, in the form of subsidies, to low-income, working families with children under age 13. These subsidies help low-income families access early care and education (ECE) for their children and support parental work or participation in education and training activities. Through their policies, states have discretion to determine who is eligible or prioritized to receive CCDF subsidies; states also play a role in managing how policy requirements are implemented in practice. These state-level policies and practices shape families’ decisions and behaviors—that is, they may facilitate or interfere with families’ use of CCDF subsidies.

This infographic highlights some of the findings from a recently published study1,2 that examined information from three publicly available sources—the CCDF Policies Database,3 CCDF grantee state plans for federal fiscal years 2016–2018,4 and lead agency websites for each state.a The study explores state-level variation in policies and practices regarding CCDF eligibility requirements, household and work documentation requirements, prioritization of TANF recipients, and availability of program information online in Spanish. This review depicts how some features of CCDF policies (as of June 2016b) and practices (as of July 2018) might shape access to CCDF subsidies for Hispanic families in 13 states. This infographic highlights three of the policy and practice dimensions included in the study: 1) minimum weekly work requirements, 2) household documentation requests, and 3) the availability of information about the program and application process in Spanish. These features may be especially relevant for immigrant and mixed-status (i.e., families in which one or more members of the household are not U.S. citizens) Hispanic families.

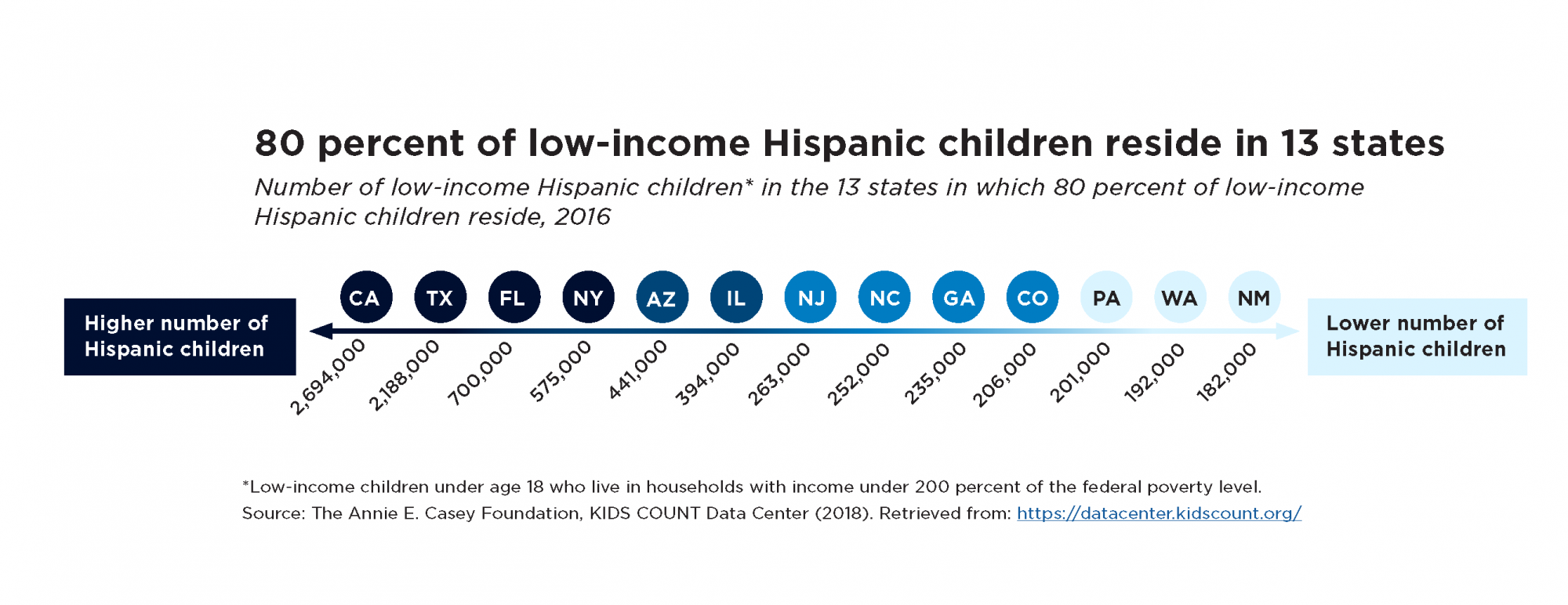

Our review focuses on 13 states with large populations of low-income Hispanic children. In 2016, 80 percent of the United States’ estimated 10.6 million low-incomec Latinod children resided in 13 states: Arizona, California, Colorado, Florida, Georgia, Illinois, New Jersey, New Mexico, New York, North Carolina, Pennsylvania, Texas, and Washington.2,5

Figure 1. 80 percent of low-income Hispanic children reside in 13 states

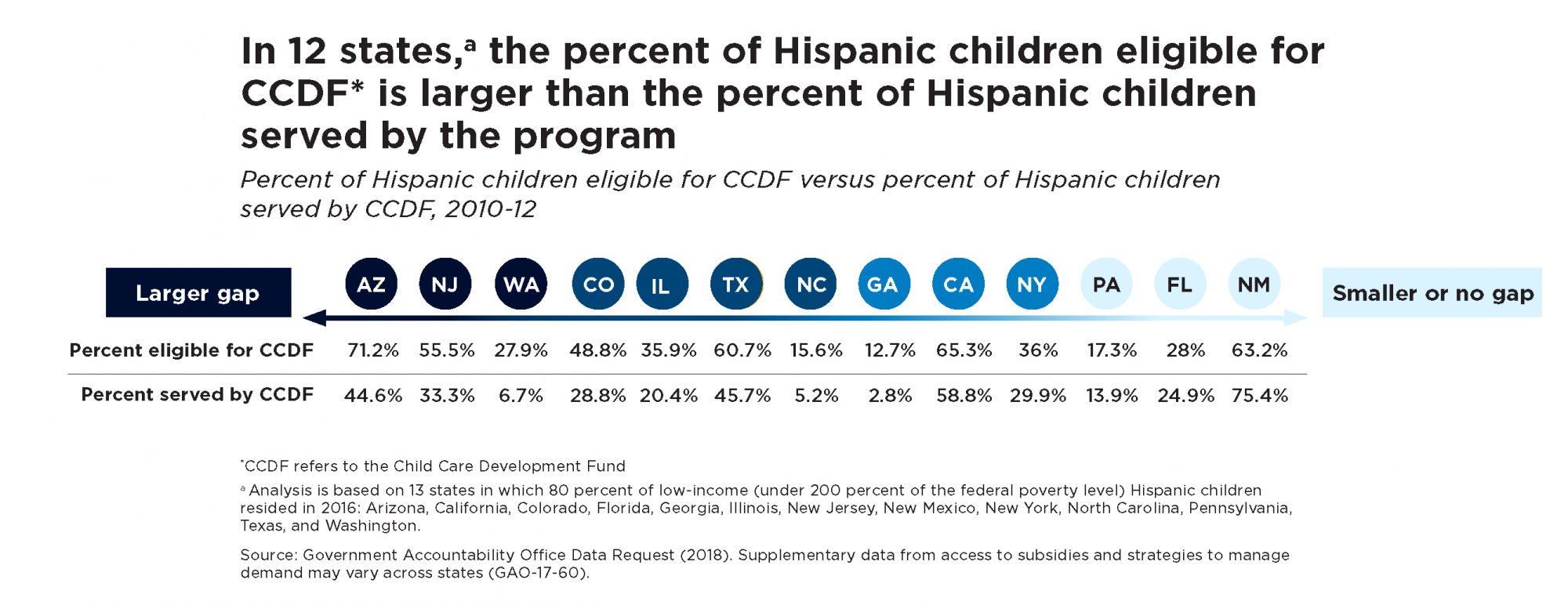

There is a gap in the percent of Hispanic families who are eligible for CCDF and the percent served by CCDF subsidies. While Hispanic children make up an estimated 35 percent of the population eligible for CCDF subsidies,e the United States Government Accountability Office estimates that just 20 percent of the population served by CCDF is Hispanic.6 In 12 of the 13 states included in this review, the share of Hispanic children eligible for CCDF is larger than the share of Hispanic children served by the program.6

Figure 2. In 12 states, the percent of Hispanic children eligible for CCDF is larger than the percent of Hispanic children served by the program

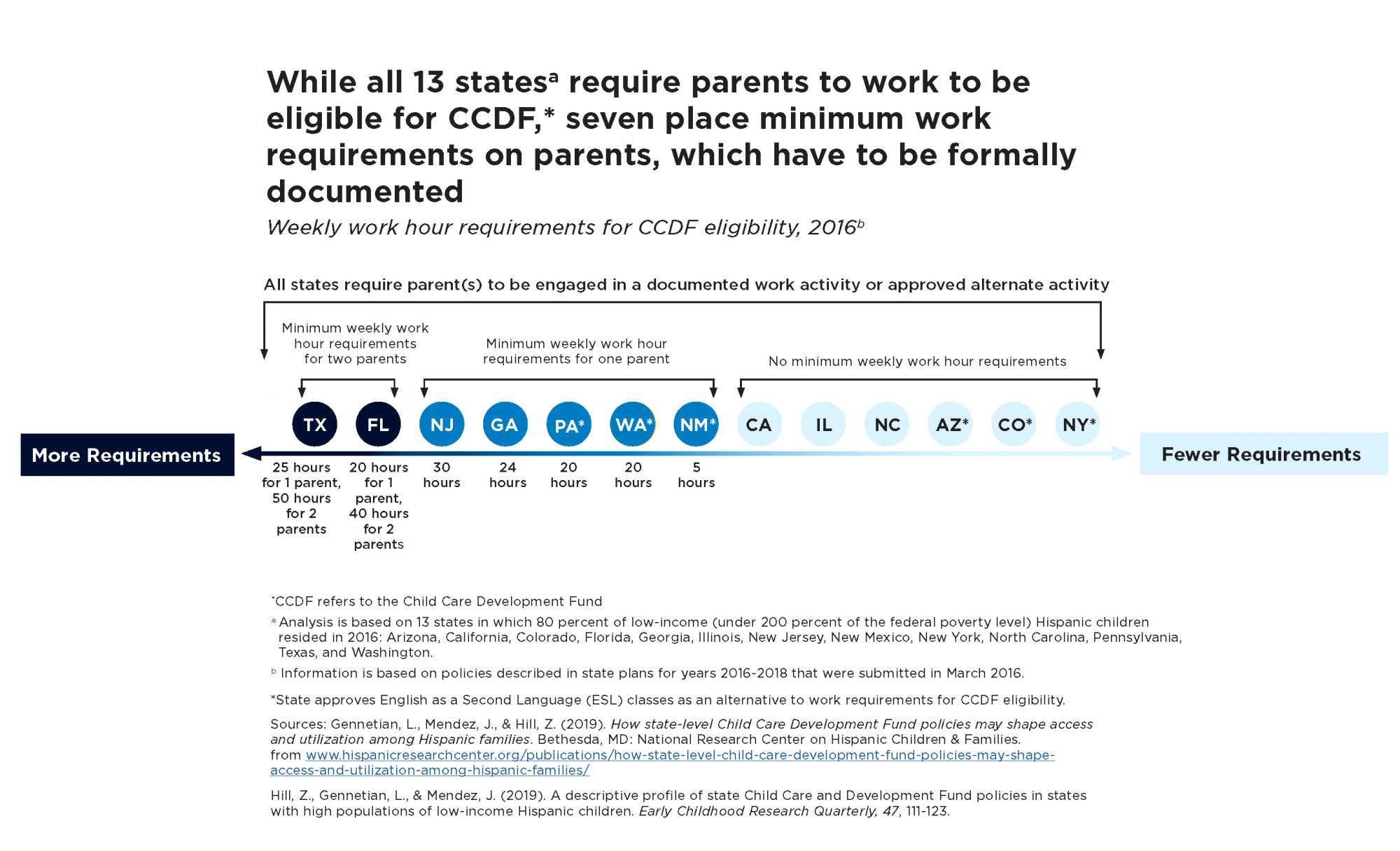

States require verification of work hours, and some place minimum work requirements on parents to qualify for CCDF subsidies.1,2 All 13 states in this review require CCDF recipients to provide documentation of work hours (e.g., pay stubs, letters from employers, etc.). Seven states impose minimum weekly work requirements on parents. Five of these states impose minimum weekly work requirements on one parent, while two impose them for both parents. Low-income Latino parents (especially fathers) tend to have high rates of employment,7 but they report high rates of nonstandard hours and frequent short notification of work schedules.7,8 This means that it can be difficult for them to document their work hours for the purpose of determining eligibility or to meet minimum requirements from week to week. Notably, six of the 13 states approve ESL classes as an alternative to work requirements, while seven states do not. Allowing ESL classes to count toward work requirements may be helpful for the approximately 2 in 3 Hispanic adults born outside of the United States who report that they do not speak English well (or at all).9

Figure 3. While all 13 states require parents to work to be eligible for CCDF, seven place minimum work requirements on parents, which have to be formally documented

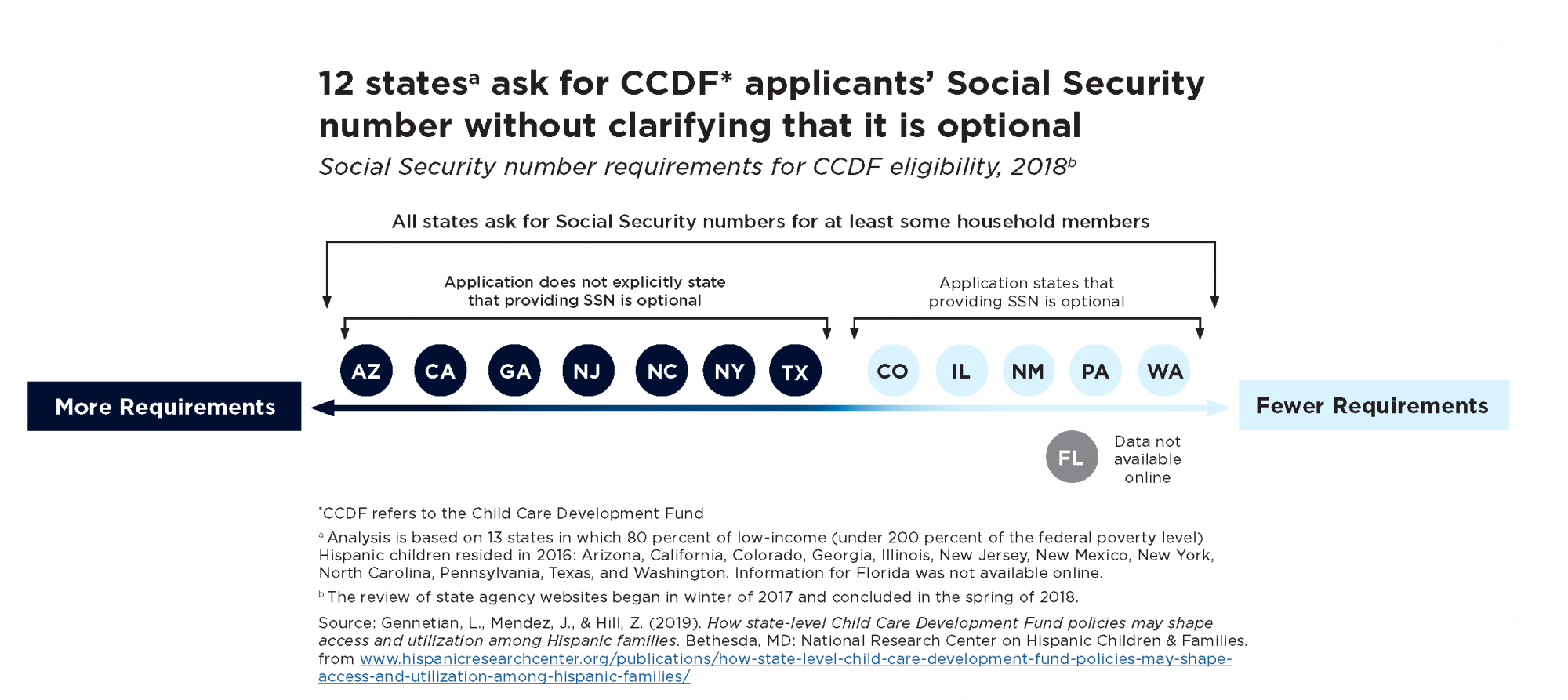

Documentation requirements for CCDF applicants may limit low-income Hispanic families’ access to CCDF.1,2 Although 94 percent of Hispanic children were born in the United States in 2014 and are U.S. citizens,10 documentation requirements during the application process may deter some Hispanic families—particularly immigrant and mixed-status families—from seeking CCDF subsidies.11,12,13 Eight of the states reviewed require CCDF applicants to provide documentation verifying household membership (e.g., birth certificates, baptismal records, marriage records, tax records, etc.).1 In addition, all 12 states for which an online application was available ask CCDF applicants to provide a Social Security number in their applications. While providing a Social Security number is not required, only five of the 12 states explicitly specify that providing the information is optional.

Figure 4. 12 states ask for CCDF applicants' Social Security number without clarifying that it is optional

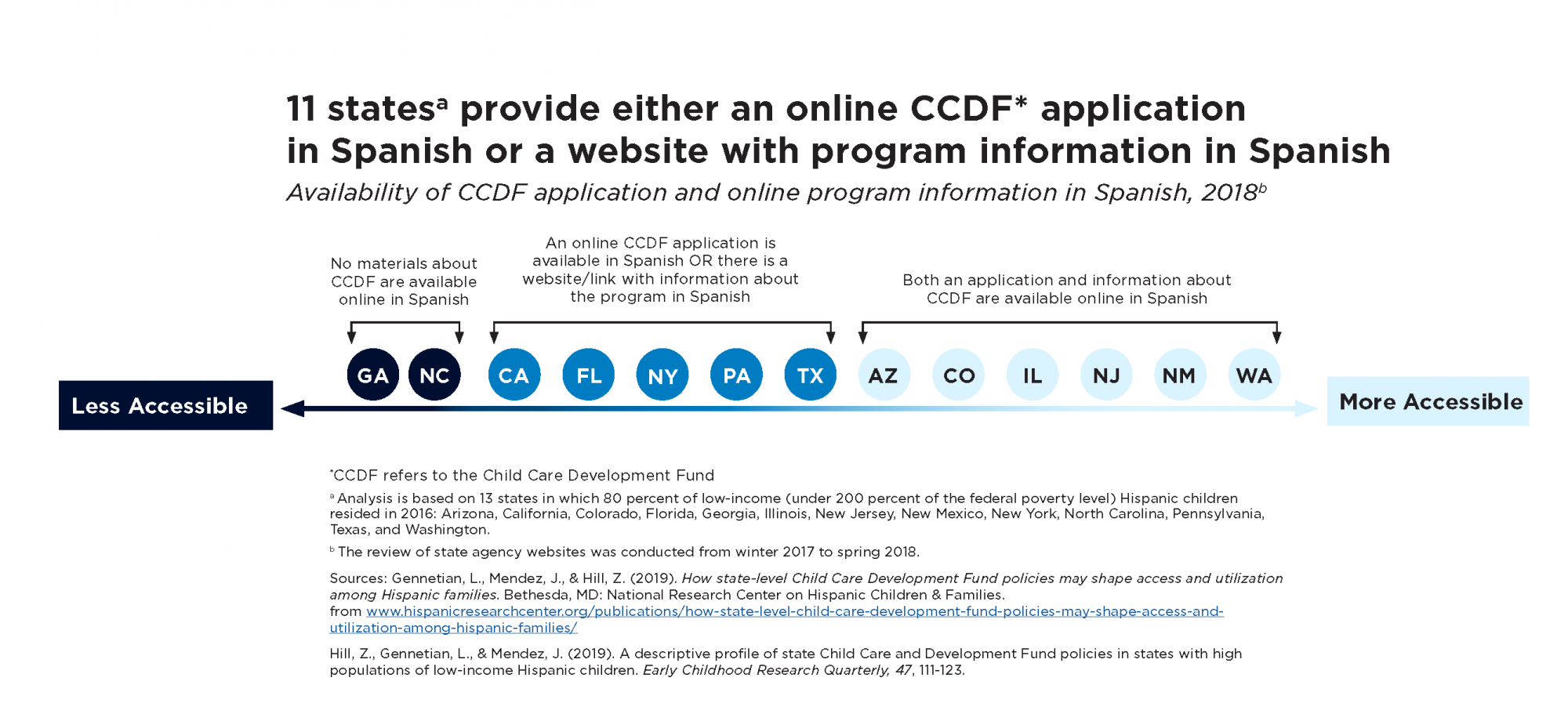

Most states provide information in Spanish.1,2 The availability of online information about CCDF in Spanish may facilitate access to CCDF subsidies among low-income Latino families, especially those with greater fluency in Spanish. Sixty-two percent of foreign-born Hispanic adults score low on English literacy skills, as do 1 in 4 U.S.-born Hispanic adults.14 Six states provide both an online application and web-based information about CCDF in Spanish; five states provide either an application translated in Spanish or offer a link within their application to a website with information about the program in Spanish. In two states, online information about the CCDF program and applications are readily accessible in Spanish.

Figure 5. 11 states provide either an online CCDF application in Spanish or a website with program information in Spanish

This infographic showcases how certain policies and practices may facilitate or inhibit access to CCDF subsidies for eligible Hispanic populations.

a This qualitative review of state agency websites was conducted from winter 2017 to spring 2018.

b This review mostly reflects policies described in state plans for fiscal years 2016–2018 that were submitted in March 2016, and therefore may not capture current policies and practices.

c Low-income is defined as living in a household with an income under 200 percent of the federal poverty level.

d The terms “Hispanic” and “Latino” are used interchangeably in this paper. The Census Bureau gives survey respondents the option of identifying themselves (or their minor children) as having origins in Mexico, Puerto Rico, Cuba, or “another Hispanic, Latino, or Spanish origin.”

e As determined by federal income and work requirements.

Suggested Citation:

Hill, Z., Gennetian, L., & Mendez, J. (2019). How state policies might affect Hispanic families’ access to and use of Child Care and Development Fund subsidies. Report 2019-04. Bethesda, MD: National Research Center on Hispanic Children & Families. https://doi.org/10.59377/971v1930l

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to thank the Steering Committee of the National Research Center on Hispanic Children & Families, and staff from OPRE, for their feedback on earlier drafts of this brief. Additionally, we thank Maria Ramos-Olazagasti for her assistance through various drafts of this publication and Sara Dean, Isabel Griffith, and Deja Logan for their research assistance support.

Editor: Brent Franklin

Designers: Susan Balding and Catherine Nichols

About the Center

The National Research Center on Hispanic Children & Families (Center) is a hub of research to help programs and policy better serve low-income Hispanics across three priority areas: poverty reduction and economic self-sufficiency, healthy marriage and responsible fatherhood, and early care and education. The Center is led by Child Trends, in partnership with NORC at the University of Chicago, New York University, University of North Carolina at Greensboro, and University of Maryland, College Park. The Center is supported by grant #90PH0028 from the Office of Planning, Research and Evaluation within the Administration for Children and Families in the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services. The National Research Center on Hispanic Children & Families is solely responsible for the contents of this publication, which do not necessarily represent the official views of the Office of Planning, Research and Evaluation, the Administration for Children and Families, or the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services. Copyright 2019 by the National Research Center on Hispanic Children & Families.

References

1 Gennetian, L., Mendez, J., & Hill, Z. (2019). How State-Level Child Care Development Fund Policies May Shape Access and Utilization among Hispanic Families. Bethesda, MD: National Research Center on Hispanic Children & Families. Retrieved from www.hispanicresearchcenter.org/publications/how-state-level-child-care-development-fund-policies-may-shape-access-and-utilization-among-hispanic-families/

2 Hill, Z., Gennetian, L., & Mendez, J. (2019). A Descriptive Profile of State Child Care and Development Fund Policies in States with high populations of low-income Hispanic children. Early Childhood Research Quarterly, 47, 111-123.

3 Minton, S., Giannarelli, L., & Stevens, K. (2015). Child Care and Development Fund (CCDF) Policies Database, 2014. Ann Arbor, MI: Inter-university Consortium for Political and Social Research. Retrieved from https://www.acf.hhs.gov/sites/default/files/documents/opre/ccdf_policies_database_2017_book_of_tables_final_10_09_18_508.pdf

4 Office of Child Care. (2016). Approved CCDF Plans (FY 2016-2018). Washington, DC: Office of Child Care.

5 The Annie E. Casey Foundation. (2018). KIDS COUNT Data Center. Baltimore, MD: The Annie E. Casey Foundation. Retrieved from https://datacenter.kidscount.org/

6 U.S. Government Accountability Office. (2016). Access to Subsidies and Strategies to Manage Demand Vary Across States Washington, DC: GAO. Retrieved from https://www.gao.gov/products/gao-17-60

7 Wildsmith, E., Ramos-Olazagasti, M. A., & Alvira-Hammond, M. (2018). The Job Characteristics of Low-Income Hispanic Parents. Bethesda, MD: National Research Center on Hispanic Children & Families. Retrieved from https://hispanicrescen.wpengine.com/publications/the-job-characteristics-of-low-income-hispanic-parents/

8 Crosby, D., & Mendez, J. (2017). How Common are Nonstandard Work Schedules Among Low-Income Hispanic Parents of Young Children? Bethesda, MD: National Research Center on Hispanic Children & Families. Retrieved from https://hispanicrescen.wpengine.com/research-resources/how-common-are-nonstandard-work-schedules-among-low-income-hispanic-parents-of-young-children/

9 Krogstad, J. M., Stepler, R., & Lopez, M. (2015). English Proficiency on the Rise Among Latinos: U.S. Born Driving Language Changes. Washington DC: Pew Research Center. Retrieved from https://www.pewhispanic.org/2015/05/12/english-proficiency-on-the-rise-among-latinos/

10 Patten, E. (2016). The Nation’s Latino Population Is Defined by Its Youth. Washington, DC: Pew Research Center. Retrieved from http://www.pewhispanic.org/2016/04/20/the-nations-latino-population-is-defined-by-its-youth/

11 Alvira-Hammond, M., & Gennetian, L. (2015). How Hispanic Parents Perceive Their Need and Eligibility for Public Assistance. Bethesda, MD: National Research Center on Hispanic Children & Families. Retrieved from https://hispanicrescen.wpengine.com/publications/how-hispanic-parents-perceive-their-need-and-eligibility-for-public-assistance/

12 Bernstein, H., Gonzalez, D., Karpman, M., & Zuckerman, S. (2019). One in Seven Adults in Immigrant Families Reported Avoiding Public Benefit Programs in 2018. Washington, DC: Urban Institute. Retrieved from https://www.urban.org/research/publication/one-seven-adults-immigrant-families-reported-avoiding-public-benefit-programs-2018

13 Sandstrom, H., Huerta, S., & Loprest, P. (2014). Understanding the Dynamics of Disconnection from Employment and Assistance: Final Report. Washington, DC Office of Planning, Research, and Evaluation, Administration for Children and Families, US Department of Health and Human Services. Retrieved from https://www.acf.hhs.gov/opre/resource/understanding-the-dynamics-of-disconnection-from-employment-and-assistance

14 Batalova, J., & Fix, M. (2015). What Does PIAAC Tell Us About the Skills and Competencies of Immigrant Adults in the United States? Washington, DC: Migration Policy Institute. Retrieved from https://static1.squarespace.com/static/51bb74b8e4b0139570ddf020/t/54da7824e4b026d7c8ca7cce/1423603748680/Batalova_Fix_PIAAC.pdf