Oct 12, 2021

Research Publication

Many Latino and Black Households Made Costly Work Adjustments in Spring 2021 to Accommodate COVID-Related Child Care Disruptions

Authors:

This data snapshot is part of a series documenting how Latino children, families, and households have been faring since the onset of the COVID-19 pandemic. Drawing from the latest publicly available data sources, each snapshot examines a specific domain of child and family well-being and provides a brief overview of social and policy context relevant to the findings. Recent snapshots focus on poverty, housing insecurity, food insufficiency, and multiple hardships experienced by Latino households with children during the pandemic.

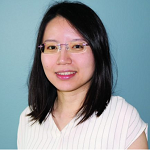

In mid-to-late Spring 2021, as many schools reopened, roughly 1 in 5 (19%) households with children reported that their children were unable to attend child care for reasons related to COVID-19. COVID-related child care disruptions were especially common among Latino and Black households: According to recent data from the U.S. Census Bureau’s Household Pulse Survey, 22 percent of Latino households, 24 percent of Black households, and 17 percent of White households reported COVID-related child care disruptions.

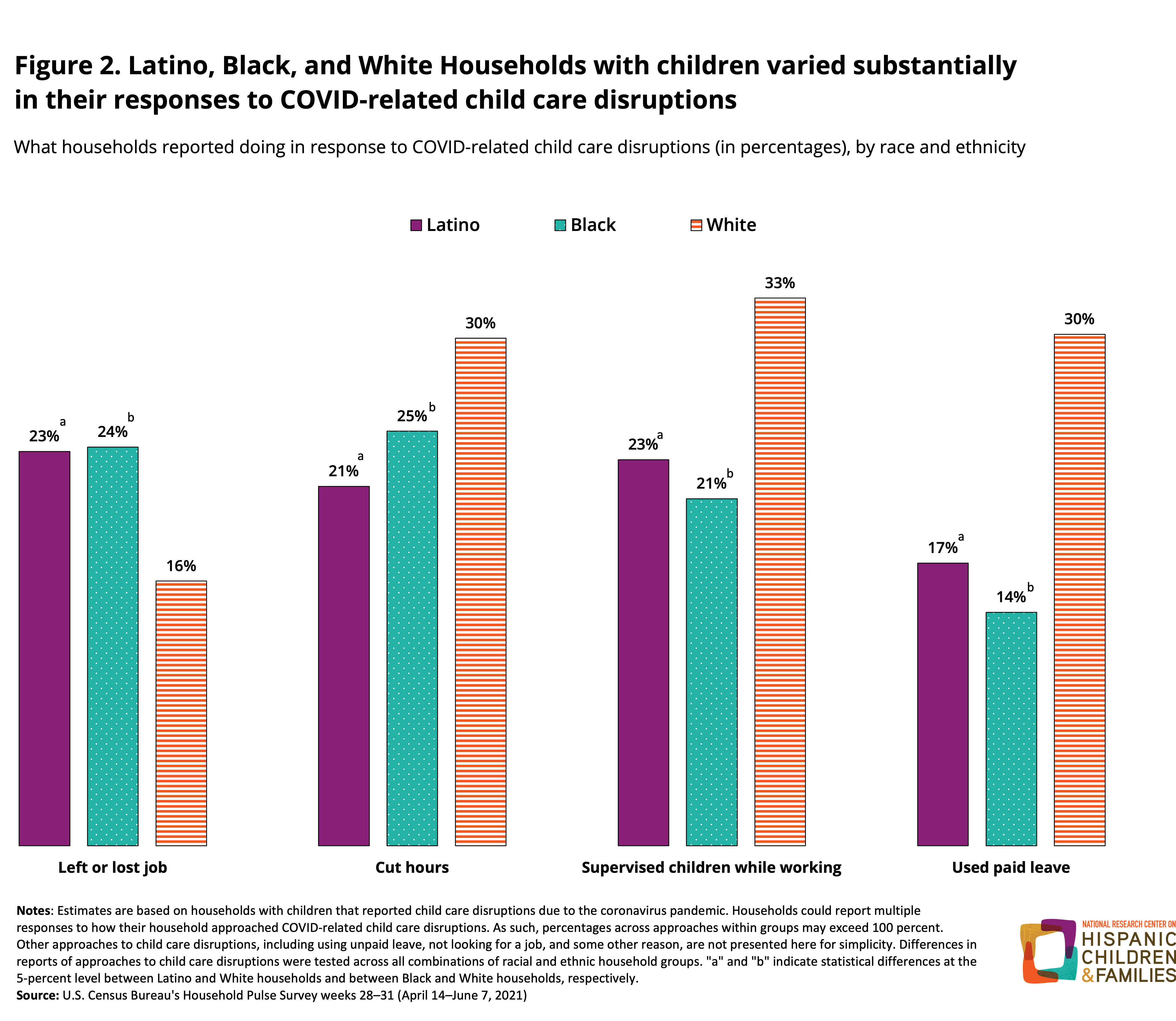

The impacts of COVID-related child care disruptions on adults’ work lives were, in many ways, particularly severe for Latino and Black households. Our analysis indicates that Latino and Black households often reported leaving or losing a job, cutting work hours, and supervising children while working in response to COVID-related child care disruptions. Although White households reported many of these same work-life adjustments, they were much more likely than Latino and Black households to report using paid leave, and less likely to report having left or lost a job in response to child care disruptions. More than 20 percent of Latino and Black households with children had an adult worker who left or lost a job; among White households with children, this number was 16 percent.

Understanding racial and ethnic disparities in responses to COVID-related child care disruptions

The COVID-19 pandemic resulted in the closure of, or reduced operations for, a substantial number of child care centers, leading to the loss of care on which many employed parents relied. The move to virtual learning also led to disruptions for many parents of school-aged children. Although child care and school closures occurred in communities throughout the nation, minority-owned child care providers that serve many Latino and Black families were at high risk of closure during the pandemic. In addition, both remote instruction and hybrid modes (mix of remote and in-person instruction) were more common in majority Latino and Black schools than in majority White districts, even when many schools and child care programs reopened in the spring. And Black and Latino families were more likely than their White counterparts to report concerns about the safety of returning their children to school or child care in the midst of an ongoing pandemic.

Moreover, due to the nature of their jobs, many Latino and Black workers faced barriers to meeting the additional caregiving responsibilities created by school and child care disruptions. Latino and Black individuals are overrepresented in low-wage jobs and in jobs that do not offer paid leave benefits or telework options. Latino and Black households also lost earnings at higher rates than White households, likely making it untenable for them to continue paying for child care while earning less income. During the pandemic, these features of work likely constrained the options available to Latino and Black households faced with COVID-related child care disruptions.

Methodology

This snapshot draws on data from the Household Pulse Survey, a Census Bureau initiative that gathers nationally representative data on how the COVID-19 pandemic has impacted households and individuals in the United States. We restricted our analytic sample to 37,310 households with children (under age 18) who answered the question about the pandemic’s impact on child care between April 14, 2021 and June 7, 2021 (and who did not indicate that this question was not applicable). The question specifically asked about COVID-related child care disruptions in the last four weeks, capturing circumstances from mid-March to early June, when most K-12 schools were still in session.

Child care disruptions were assessed with a question on whether any children under age 18 in the household were unable to “attend daycare or another child care arrangement in the last 4 weeks because of the coronavirus pandemic.” Those with any child care disruptions were asked whether, in order to care for the children, any adult in the household, including themselves, (1) took unpaid leave; (2) used vacation, sick days, or other paid leave; (3) cut hours; (4) left a job; (5) lost a job; (6) did not look for a job; (7) supervised one or more children while working; (8) other; or (9) none of the above. Respondents were able to select all responses that applied. For this snapshot, we combined responses for losing a job and leaving a job.

The prevalence of child care disruptions and the work-related consequences of those disruptions are presented separately for Latino, Black, and White households with children. Race and ethnicity is defined by the respondent’s reported race and ethnicity. We conducted statistical tests to compare (1) Hispanic and Black households, (2) Hispanic and White households, and (3) Black and White households. In the second figure, we present the approaches to child care disruptions for which statistical differences across groups have been found. We applied household weights to all analyses.