Mar 13, 2024

Research Publication, Research Series

Nearly Half of Hispanic Children in Households With Low Incomes Used Early Care and Education in 2019

Authors:

Access to high-quality early care and education (ECE) arrangements supports children’s development and households’ economic well-being, a link that may be especially critical to understand for children in Hispanic households with low incomes. Using data from the 2019 National Survey of Early Care and Education, this brief finds that nearly half of Hispanic children in households with low incomes used ECE in 2019, but usage patterns varied by child age and whether the household included immigrant members.

Introduction

Public investment in early care and education (ECE) opportunities for children who live in households with low incomes has expanded over the last decade, with research showing that access to ECE supports children’s growth and development.1 When child care arrangements support parents’ work opportunities and schedules, family economic well-being may increase as well2—but only when those child care arrangements have minimal disruptions.3

Understanding the relationship between child care stability and children and families’ well-being may be especially important for Hispanics in the United States. The Latino population is one of the fastest-growing and largest racial and ethnic groups in the United States today4; they also experience high rates of poverty. As a result, it is important to understand access to and utilization of early care and education among Hispanica families with low incomes, defined here as households with incomes at or less than 200 percent of the federal poverty line.

Research shows that many Latino households are underserved by ECE programs. National data indicate that, while 3 in 4 Latino households can find no-cost and lower-cost ECE arrangements (defined as less than 7% of their household budget) that meet their needs, 1 in 4 households using ECE are paying high costs that exceed recommended thresholds.5 Moreover, state-level estimates for child care subsidy receipt show that, relative to other households with low incomes, Hispanic households are underserved by child care subsidy programs.6 Finally, many Hispanic households encounter barriers when searching for ECE arrangements, including insufficient knowledge of how to apply for programs, language barriers interacting with office staff, and difficulty providing eligibility documents needed for applications. Together, such factors prevent these households’ uptake of the financial supports needed for ECE program enrollment and may result in lower access to and use of ECE by Latino households.7

In this brief, we use the most recently available nationally representative dataset on ECE utilization—the 2019 National Survey of Early Care and Education (NSECE)8—to provide a snapshot of ECE use among children in households with low incomes, with a focus on Hispanic children in immigrant and non-immigrant families. We also update our earlier analysis comparing ECE use among Latino, Black, and White households using the 2012 NSECE to identify and monitor racial and ethnic gaps in ECE use.b We define ECE as any center-based; home-based; and family, friend, and neighbor (FFN) care arrangements that children experience when they are not in the care of their parents or guardians.

We first focus our analysis on the percentage of young children participating in nonparental care who live in Hispanic households with low incomes—including both immigrant and non-immigrant households—relative to non-Hispanic households. Next, we provide an overview of the different types of ECE options that Latino families use, namely, center-based and home-based options. We then offer estimates of the percentage of families from different racial and ethnic backgrounds who use multiple ECE arrangements. Finally, we assess how these national estimates of ECE utilization for Latino children from the 2019 NSECE compared to those from the 2012 NSECE. Point-in-time comparisons of these cross-sectional data offer insight as to how population-level rates may have changed or sustained.

Key Findings

Hispanic ECE Access Data Series

Reports in this series draw on nationally representative data from the 2019 National Survey of Early Care and Education (NSECE) to describe multiple aspects of early care and education (ECE) access and utilization for Hispanic households with low incomes who have young children. The series presents estimates on the availability, flexibility, and affordability of care, as well as the characteristics of settings and providers serving Hispanic children from households with low incomes. Descriptive analyses in this report update similar analyses focused on ECE access for Latino families that drew from 2012 NSECE data and provide a comprehensive picture of the landscape of ECE just prior to the onset of the COVID-19 pandemic. The cross-sectional design of these surveys allows researchers to also monitor trends and shifts in the data. For more information, readers are encouraged to review other reports in the series, as well as our synthesis on ECE access for Latino families.

In 2019, nearly half of Hispanic children younger than age 6 who lived in households with low incomes used early care and education (ECE).

Preschool-age Hispanic children used ECE at higher rates than children younger than age 3, and ECE rates were higher for Hispanic infants and toddlers in non-immigrant households than among those in households with an immigrant member.

Among Hispanic children from households with low incomes who participated in ECE, use of different types of care providers—center- or home-based—varied by child age and by whether their household included an immigrant member.

In general, among children from Latino households with low incomes who participated in care, we found that:

- Center-based care was more common for preschool-age children than for younger children, and more common for preschoolers from immigrant households than those from non-immigrant households. About two thirds of Hispanic preschool-age children from immigrant (64%) and non-immigrant (54%) households with low incomes used center-based care. Roughly one in four Latino infants and toddlers from immigrant and non-immigrant households attended center-based care.

- Most Hispanic infants and toddlers in both immigrant and non-immigrant households were in home-based care (>80%). Among preschool-age children, those in non-immigrant households were more likely to be in home-based care (63%) than those in immigrant households (47%).

- The type of home-based provider households used also varied by whether households included an immigrant member; children from immigrant Latino households with low incomes were less likely to be in unpaid home-based care than those from non-immigrant Latino households.

Participation in multiple ECE arrangements was common for children from most racial and ethnic groups in households with low incomes, but significantly less so for Hispanic children from immigrant households.

- Just 25 percent of preschool children and 33 percent of infants and toddlers from Hispanic immigrant households with low incomes were in multiple ECE arrangements, which is significantly lower than their same-age peers (46-55% of whom had multiple arrangements).

In 2019, overall rates of ECE use among Latino children from households with low incomes did not differ significantly from 2012 rates, especially among preschoolers. However, findings on type of care used suggest that Latino households with low incomes relied on home-based care to a greater extent in 2019 than in 2012.

- Based on cross-sectional comparisons, we found similar rates of ECE use among Latino children in households with low incomes in both 2012 and 2019; this was especially the case for preschool-age children.

- We also found evidence that households with low incomes (including Latino households) were more likely to use home-based care options in 2019 than in 2012.

- Among Hispanic children in non-immigrant households with low incomes, a larger percentage of infants and toddlers—but a smaller percentage of preschool-age children—were in multiple care arrangements in 2019 than in 2012.

- This set of cross-sectional findings suggests that policymakers should prioritize supports that reach all providers—especially home-based providers who provide care for Latino children at substantial (and potentially increasing) rates.

Taken together, our findings on 2019 ECE utilization patterns among young children in Latino households with low incomes show that nonparental child care is relatively common for this group (experienced by 1 in 2 children)—and especially for preschool-age children, who tend to be in center-based programs. At the same time, many Latino preschoolers from households with low incomes also receive care from home-based providers, which is the predominant arrangement for infants and toddlers. High rates of home-based ECE use could reflect households’ needs for flexible care options to support work schedules, and for care that is more affordable. While center-based care is often subsidized or offered at no cost, it may be less available in some Latino communities, serve a narrower child age range, and/or may not meet the nonstandard work schedule needs prevalent among many Latino households with low incomes.2

Results

Proportion of Latino children in households with low incomes in ECEc

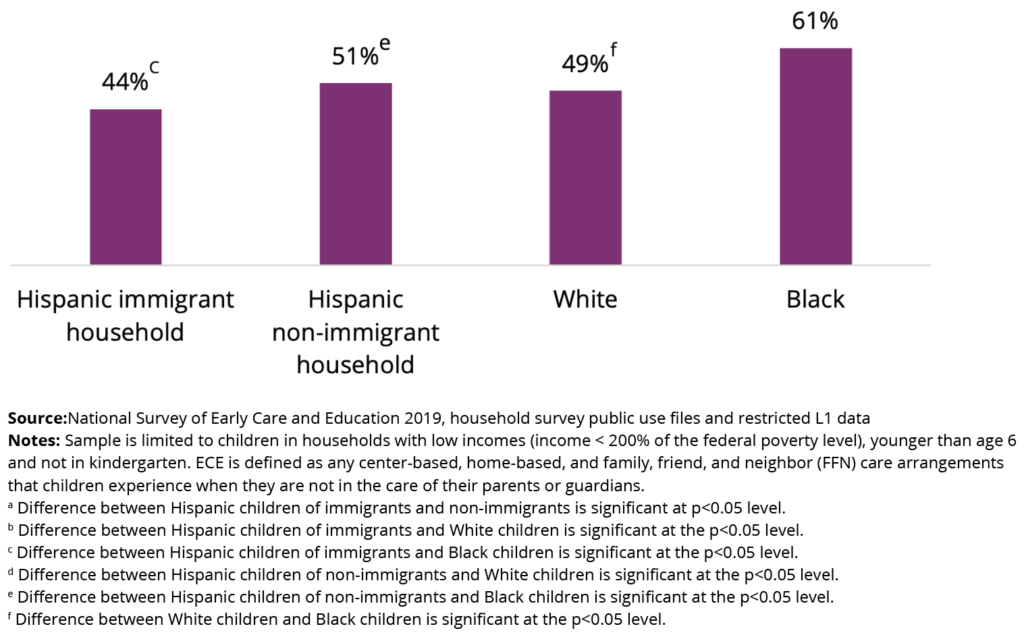

In 2019, about half of Latino children under age 6 residing in households with low incomes were using nonparental care (e.g., ECE). ECE utilization rates were higher among children from non-immigrant households than among their peers from immigrant households (see Figure 1); these differences, however, were not statistically significant. Fifty-one percent of Latino children from non-immigrant households and 44 percent of Latino children from immigrant households were in some form of nonparental care. ECE utilization rates among Latino children in households with low incomes were comparable to those among White children, but were lower than among their Black peers, whose rates of utilization were the highest of the sample.

Figure 1. Hispanic children in households with low incomes had moderate rates of ECE use in 2019

Percentage of children from households with low incomes utilizing any ECE, by race and ethnicity, 2019

The Importance of National Data on ECE Use

Nationally representative studies, such as the National Survey of Early Care and Education (NSECE), that assess families’ use of ECE help us uncover potential unmet needs facing parents with young children, as well as barriers to ECE use across different subgroups in the United States. Moreover, understanding how Latino children’s ECE participation may have changed over time can inform specific policy priorities and identify where gaps remain in our ability to provide ECE opportunities for this population. Finally, this study offers a context for understanding ECE use patterns among Latino children just prior to the disruptions of the COVID-19 pandemic and allows for comparisons going forward during the post-pandemic recovery.

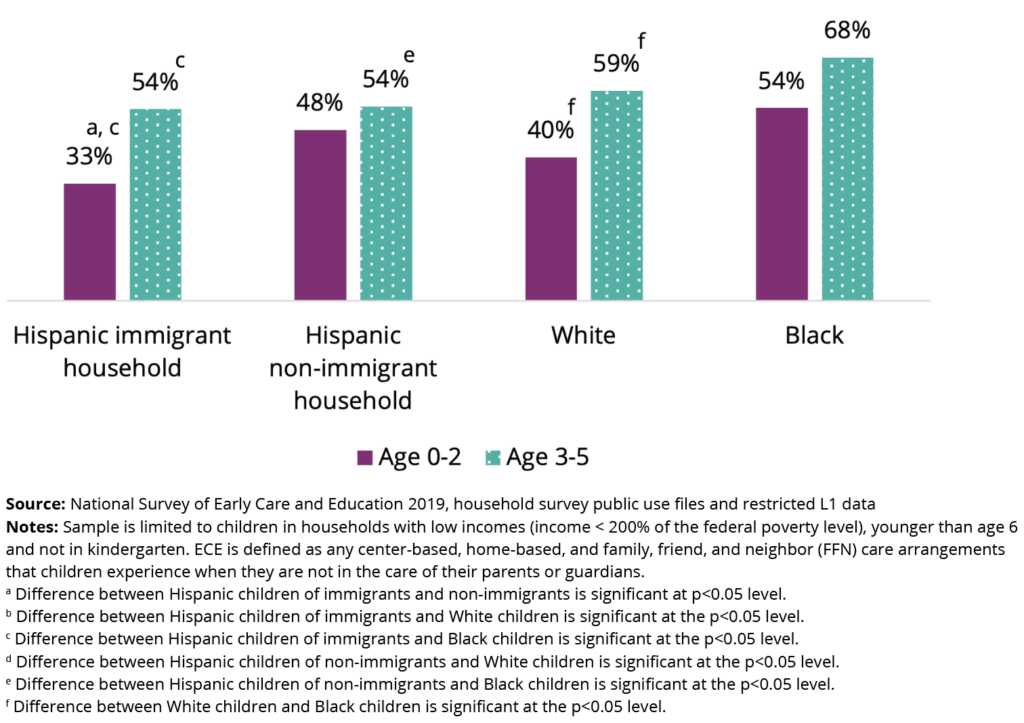

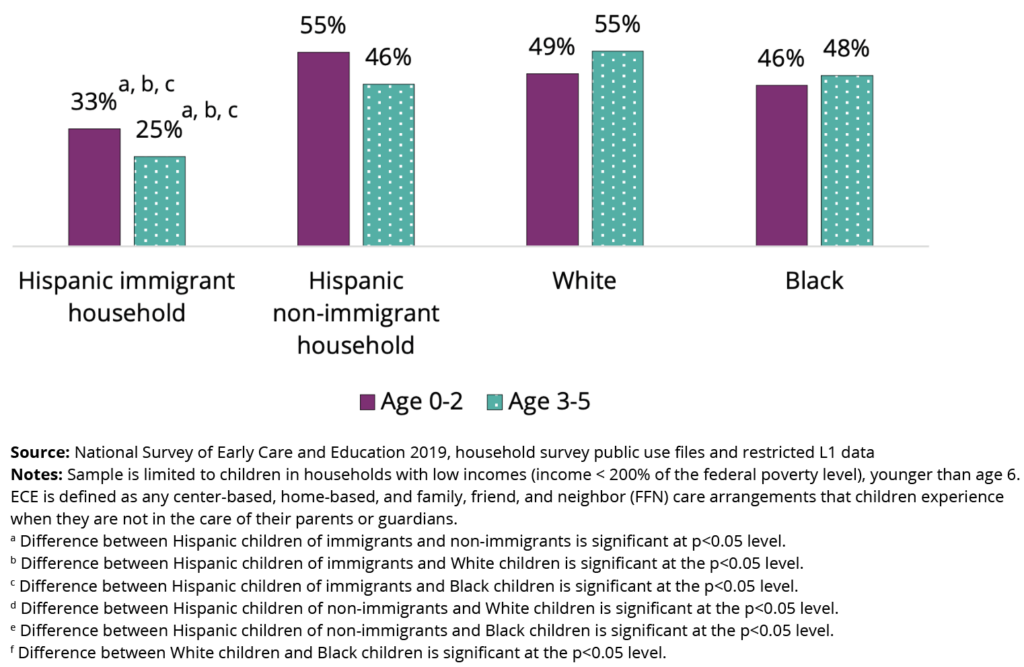

In 2019, use of ECE arrangements among Latino children varied by age of child (Figure 2). Over half of Hispanic preschool-age children (ages 3 to 5) from immigrant and non-immigrant households with low incomes were in ECE arrangements (54%). A different picture emerges among Latino infants and toddlers, with rates of ECE use lower among those from immigrant households than among those in non-immigrant households. Approximately one third of Hispanic infant- and toddler-age children in immigrant households were in ECE arrangements (33%), while nearly half of their non-immigrant Hispanic peers participated in ECE (48%); this difference of 15 percentage points is statistically significant. ECE use among Latino preschoolers (from immigrant and non-immigrant households) was similar to that of their White peers but was lower than among their Black peers. ECE use among Latino infants and toddlers was again similar to rates among their White peers. However, while Latino infants and toddlers from non-immigrant households participated in ECE at similar rates to Black infant and toddlers, those from immigrant households participated at significantly lower rates than their Black peers.

Figure 2. More than half of Hispanic preschoolers from households with low incomes were in ECE, with less use among infants and toddlers—especially those in immigrant Hispanic households

Percentage of children from households with low incomes in any regular ECE arrangements, by child age, race, and ethnicity, 2019

Proportion of Latino children in households with low incomes in center-based care arrangements

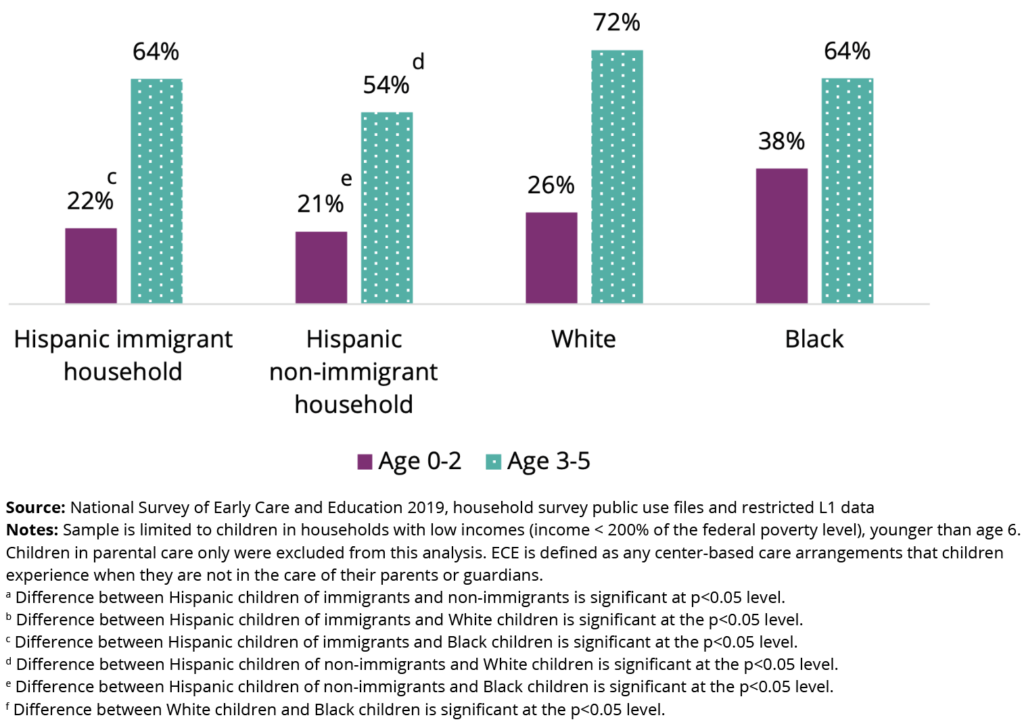

The majority of Latino preschool-age children in ECE used center-based care in 2019. Roughly two thirds of Hispanic preschool children in immigrant households (64%) and over half of Latino children in non-immigrant (54%) households with low incomes participated in center-based care. However, Hispanic children from non-immigrant households—but not those from immigrant households—were significantly less likely to use center-based care when compared to White households with preschool-age children. Center-based care use was also much less common among infants and toddlers. Among those younger than age 3, roughly 1 in 5 Hispanic children from immigrant (22%) and non-immigrant (21%) households were in center-based care. We found no differences between White and Black children in use of center-based care; however, Black children were significantly more likely to use center-based arrangements than Hispanic non-immigrant and immigrant households (Figure 3).

Figure 3. Roughly two thirds of Hispanic preschool-age children in immigrant households and over half of Hispanic preschool children in non-immigrant households participated in center-based care

Percentage of children from households with low incomes in ECE who had any center-based arrangements, by child age, Hispanic immigrant or non-immigrant household status, and race and ethnicity, 2019

Proportion of Latino children in households with low incomes in home-based care arrangements

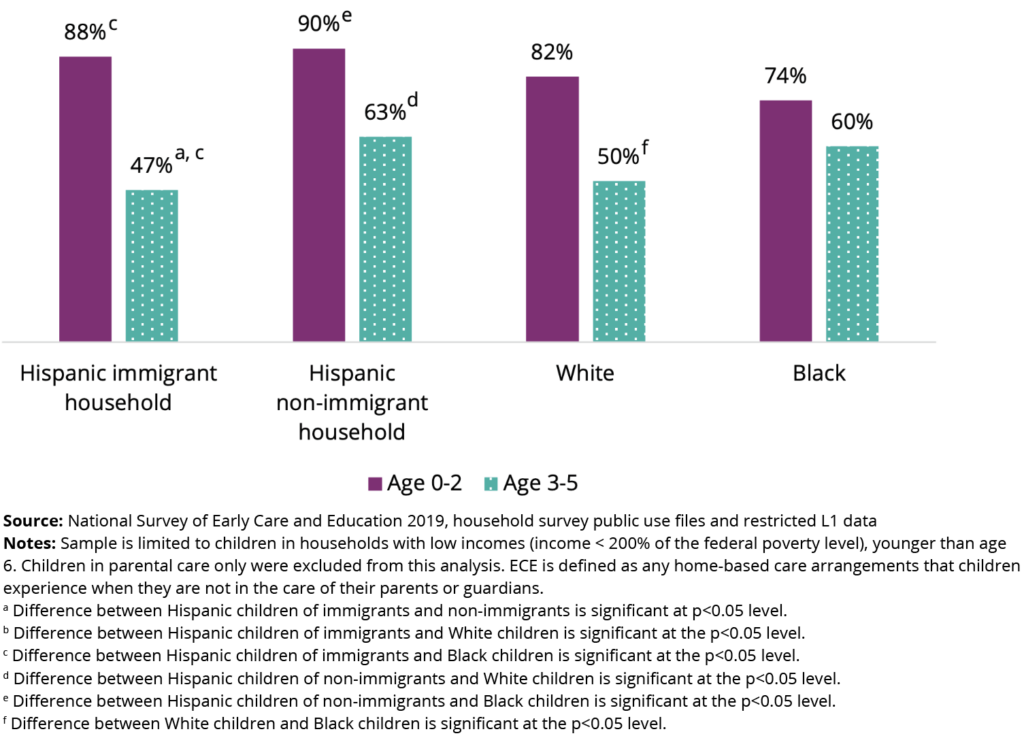

Among Latino children from households with low incomes that used ECE,dmost infant- and toddler-age children were served by home-based arrangements, with a large portion of children ages 3 to 5 also in home-based care (Figure 4). Roughly 9 in 10 Hispanic children younger than age 3 in both immigrant (88%) and non-immigrant (90%) households with low incomes participated in home-based care. Among Hispanic children ages 3 to 5, those in non-immigrant households with low incomes (63%) were significantly more likely to be in home-based care than their counterparts in immigrant families (47%). Latino children from both immigrant and non-immigrant households were significantly more likely than Black children to be in home-based care arrangements (74%). Lastly, White children ages 3 to 5 from households with low incomes were significantly less likely to participate in care than Black children.

Figure 4. Hispanic immigrant and non-immigrant infants and toddlers from households with low incomes experienced high use of home-based ECE

Percentage of children from households with low income in ECE who had any home-based ECE arrangements, by child age, Hispanic immigrant or non-immigrant household status, and race and ethnicity, 2019

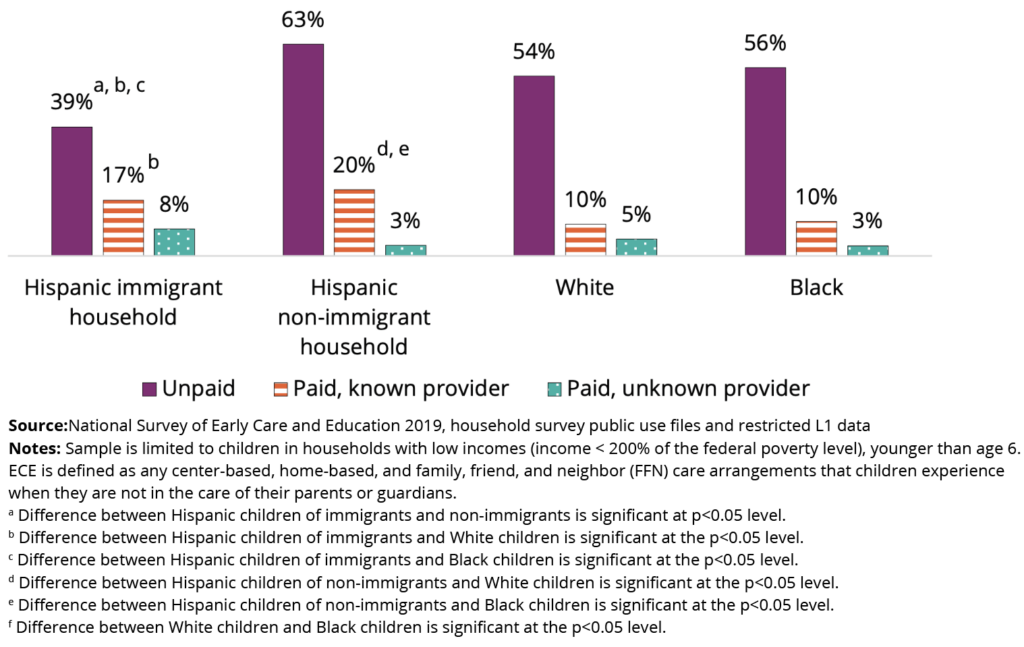

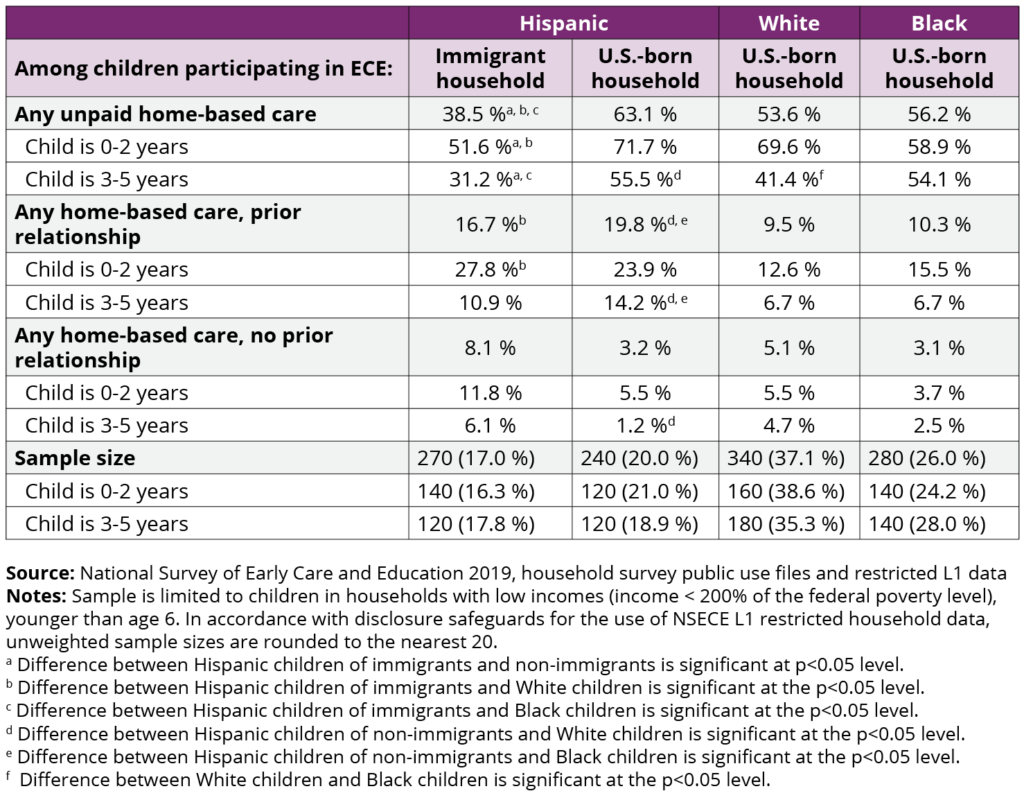

Parents may have access to different types of ECE providers, based on their knowledge and social networks. For example, parents may be able to secure unpaid nonparental care arrangements from people who are familiar or known to them (referred to as friend, family, or neighbor care, or FFN), while others might pay for care from an ECE provider who is not familiar to them. Figure 5 shows households’ use of the types of home-based care reported in the NSECE (2019): unpaid providers, paid familiar (or known to the family) providers, and paid unfamiliar (or unknown to the family) providers.

Hispanic children in immigrant families with low incomes were least likely to be in an unpaid home-based arrangement (39%), relative to their Hispanic non-immigrant (63%), White (54%), and Black (56%) peers. Hispanic children in immigrant (17%) and non-immigrant (20%) households were significantly more likely to use a paid provider known to the family, relative to their White (10%) peers. Children in Hispanic non-immigrant households were also significantly more likely to use a paid provider known to the family relative to their Black (10%) peers. Additionally, across all groups, a small percentage of children (3%-8%) participated in a paid home arrangement provided by an unknown provider, defined as having no prior relationship with the family. Securing regular use of familiar home-based providers who provide care at no cost is challenging for immigrant households due to their lack of knowledge and lack of established social networks in their local community.

Figure 5. Immigrant Hispanic households were least likely to use unpaid home-based care, while all Hispanic households were significantly more likely to use paid and familiar home-based care

Percentage of children from households with low incomes in ECE who had three types of home-based care arrangements, by Hispanic immigrant and non-immigrant households, and race and ethnicity, 2019

Proportion of Latino children in households with low incomes in two or more ECE arrangements

Many Latino children in households with low incomes participate in multiple ECE arrangements (Figure 6). While rates among Hispanic non-immigrant, White, and Black children were about 50 percent in 2019, children from immigrant Hispanic households were significantly less likely to participate in multiple care arrangements regardless of age. One third of children in immigrant households with low incomes used multiple arrangements while just 25 percent of 3- to 5-year-olds used multiple arrangements. Although not significantly different, Hispanic non-immigrant households with preschoolers had the highest average use of multiple arrangements (along with White children) at 55 percent. This may be consistent with immigrant children having more limited social networks to provide parents with options for securing more than one arrangement.

Figure 6. Children from Hispanic immigrant households with low incomes were least likely to have two or more child care arrangements

Percentage of children in households with low incomes who had two or more care arrangements, by child age, Hispanic immigrant or non-immigrant household, and race and ethnicity, 2019

Spotlight on 2019 ECE utilization patterns relative to those in 2012 for children from families with low incomes

Studying ECE utilization patterns over time can offer insight into how the child care needs of Latino families with low incomes may change or vary, which could inform what investments are needed to ensure equitable access to child care resources. In this spotlight, we present select analyses to show how ECE utilization patterns reported in this brief contrast with the last nationally representative snapshot of ECE utilization as assessed by the NSECE in 2012. Because the survey methodology and questions are generally the same, we statistically compared rates of nonparental care among Latino children reported by two samples of Latino children in families with low incomes at two time points. That is, we present here a comparison of point-in-time snapshots of nationally representative households at the time of each survey; these comparisons are not intended to be longitudinal in nature.

Overall, from 2012 to 2019, we found no statistically significant differences in the percentages of Latino children from households with low incomes who were reported to be in ECE arrangements. Age patterns observed in 2019 for Latino children were also replicated, with a smaller share of Latino infants and toddlers using ECE relative to preschool-age children than in 2012. One aspect of ECE utilization where we find significant differences between the two timepoints is in the types of care arrangements used by families. A significantly larger share of Latino families reported using home-based care in 2019 than in 2012; this is also true among White and Black children, and among both immigrant and non-immigrant Hispanic households. Additionally, there were significant differences in the proportions of Latino children reported to be in multiple arrangements in 2019 versus 2012. A larger percentage of Latino infant and toddler-age children in non-immigrant Hispanic households were in two or more arrangements in 2019 than in 2012. Alternatively, a smaller share of Latino preschool-age children in non-immigrant Hispanic households were in two or more arrangements in 2019 than in 2012.e

These results may suggest that using more than one care arrangement is increasingly necessary for some Latino families with low incomes to support the demands of their work schedules. Accessing more than one arrangement also requires careful coordination among the types of care available to parents. Importantly, the use of multiple arrangements may increase overall child care costs for Latino households and increase family pressures, especially if costs exceed the federally recommended affordability threshold of costs no greater than 7 percent of household income. Alternatively, use of unpaid/paid care combinations could be a strategy to reduce costs. High rates of unpaid home-based ECE in the 2019 sample, especially among non-immigrant Hispanic households, suggest that using unpaid arrangements may be a strategy to help Hispanic families contain the costs of ECE.

Summary and Implications

This brief offers new information, from 2019, about ECE use patterns among young Hispanic children residing in households with low incomes in the United States, alongside data on their White and Black peers. Such comparisons to other groups provide important context for understanding how Latino children fare in the overall landscape of child care utilization. Generally, the relatively high use of child care arrangements among all groups we analyzed suggests ECE’s importance for child development and as a likely work support for many families with young children. Importantly, Latino children from both immigrant and non-immigrant households used ECE at similar rates from the 2012 to the 2019 NSECE data cycles. Finally, our analysis indicates that home-based care became an increasingly important setting for young Hispanic children in 2019, suggesting that changes to further strengthen home-based and FFN care will improve the overall system of care for Latino families.

Among Latino children from households with low incomes, we found that about half were using nonparental care on a regular basis in 2019. We also found that age matters for infants and toddlers from immigrant Hispanic households with low incomes, who used ECE at significantly lower rates than their Hispanic peers from non-immigrant families. This indicates that, as a group, immigrant Hispanic children may face greater challenges accessing ECE as their households experience greater barriers to locating care arrangements. Overall, our findings can inform how policies and practices to reach Hispanic children could be adjusted to ensure equitable access across immigrant and non-immigrant Hispanic households and for infants and toddlers.

For example, ECE research with Latino families shows that families must balance a range of factors to secure care that meets their needs. Families need to consider the cost, availability, flexibility, and quality of care arrangements, including whether programs/providers offer culturally responsive care for their children.4 Recent analyses show that, while some Hispanic households are able to locate no-cost center-based care within their community, many others find insufficient supply, fully enrolled centers, or hours of operation that do not support their work schedules—especially for those families with nonstandard work hours.2 Additionally, center-based care that is not subsidized is expensive, so Latino families may not find these arrangements affordable, particularly when they are looking for care for infants/toddlers rather than more affordable arrangements for preschool children.9 Taken together, factors like cost and availability can lead to changes in households’ utilization rates of center- and home-based care. These constraints might also help explain why non-immigrant Hispanic households of infants and toddlers report the highest rates (55%) of using multiple ECE arrangements to meet their needs.

Studies have shown that parents often choose home-based providers due to their familiarity, affordability, and flexibility of hours.10 In this study, we found high rates of utilization of home-based providers by all racial/ethnic groups with low incomes. The highest rates of use of unpaid home-based care were reported for children in non-immigrant Hispanic households. Future research should aim to better understand parental decision making and selection of care arrangements. Home-based providers often do not receive child care subsidies11 and are of lower quality;12 however, to ensure equity, policymakers should consider how to increase the quality of home-based care options, as such arrangements are often chosen by Hispanic households and home-based providers are more likely to be of Latina backgrounds.13

Lastly, many Hispanic children in households with low incomes rely on more than one ECE arrangement as part of their child care utilization profile. However, the precarious nature of child care arrangements and disruptions is heightened when families rely on more than one provider for their care, and research has shown that Hispanic and Black families are less likely to have access to paid work leave or work-from-home options when faced with child care disruptions.14 Thus, policies that support increased access to affordable child care for families or paid leave can help minimize disruptions for families and the businesses that rely upon their participation and contributions.

Limitations

The NSECE 2019 survey is the most recent data available on households’ ECE utilization. However, these data were collected prior to the onset of the COVID-19 pandemic, which altered the landscape of child care availability. Specifically, the health and safety demands created by the pandemic caused many program closures, which unfortunately led to permanent closures.15 Therefore, researchers should continue monitoring ECE utilization with nationally representative samples like the 2024 NSECE to survey current trends and ensure that ECE opportunities are reaching Latino households with low incomes. Given that COVID-19 showed greater negative economic and health impacts on Latino households with low incomes,16 we also recommend that future studies continue to disaggregate and analyze utilization patterns by immigrant and non-immigrant household type, program or provider type, and child age. This will ensure accurate data to inform supports needed to ensure that ECE opportunities reach Hispanic households.

Data Source and Methodology

The 2019 National Survey of Early Care and Education (NSECE) is a set of four nationally representative surveys that describe the ECE landscape in the United States. The data reported in this brief utilize public use and L1 restricted data from the NSECE nationally representative sample of households with children under age 13. Respondents reported on all regular nonparental care arrangements used in the week prior to the survey for each child in the household younger than age 13.

The estimates presented here were calculated using the NSECE Household Public Use file and Level 1 restricted data disaggregated to the child level. Our analysis focuses on young children (birth through age 5,f not yet in kindergarten) who were living in households with low incomes, defined as annual incomes below 200 percent of the federal poverty threshold. The NSECE oversampled in low-income areas, resulting in large numbers of such households. Our analytic sample is made up of 3,400 children,g of whom 1,680 are Hispanic (1,040 in immigrant households and 640 in households with U.S.-born adults only), 1,000 are non-Hispanic White children, and 740 are non-Hispanic Black children (White and Black children were from non-immigrant households; see “Definitions” below). Children of other racial/ethnic backgrounds were not included in this analysis due to small sample sizes.

We conducted descriptive analyses across several measures of children’s participation in ECE arrangements, testing the statistical significance of mean differences between racial/ethnic groups. Significant differences are noted in the text, figures, and summary tables. We use consistent notation (a-f) for each pairwise difference for clarity; if one of the letters does not appear in a specific figure or table, it means that the difference was non-significant for that outcome. All analyses were conducted in STATA and were weighted to be representative of children living in U.S. households in 2019.

Variable Definitions

Households with low incomes: Children in households that reported an annual income below 200 percent of the federal poverty threshold.

Household immigrant household: Reported that at least one household member had been born outside of the United States.

Household non-immigrant household: Reported that all household members were U.S.-born.

Nonparental care: Defined by the NSECE study and in this analysis as any nonparental care arrangements used on a regular basis for 5 or more hours per week. This includes various types of center- and home-based arrangements as well as other types of regularly scheduled nonparental care (e.g., organizational ECE settings, extracurriculars, school-based care).

Center-based care: This indicator captures all center- or organization-based ECE arrangements that children participate in for at least 5 hours per week (e.g., Head Start, public pre-K, community-based child care, drop-in care, single- activity care or lessons, and church child care during services).

Home-based care: This indicator captures any regular care arrangement provided by an individual in a home-based setting for at least 5 hours per week. It includes care that occurs in the child’s home or the provider’s home, including family child care homes. Home-based care also may or may not be paid providers.

Irregular care: This indicator captures arrangements (center-or home- based) that children participate in for less than 5 hours per week (e.g., emergency or intermittent arrangements). Children may have multiple irregular arrangements that together total more than 5 hours of care per week.

Multiple care arrangements: Identifies children who were in multiple arrangements (i.e., two or more providers). These could be providers within the same category or type of child care, or across different types of care. For the purposes of this brief, we examine the percentage of children whose primary arrangement is center-based or whose primary arrangement is home-based.

Primary care arrangement: This variables relies on how many hours children spent in each of the eight types of care over the week prior to the interview. From this information, we identified the type of arrangement in which the child spends the most time. We report the percentage of children whose primary arrangement is center-based or whose primary arrangement is home-based.

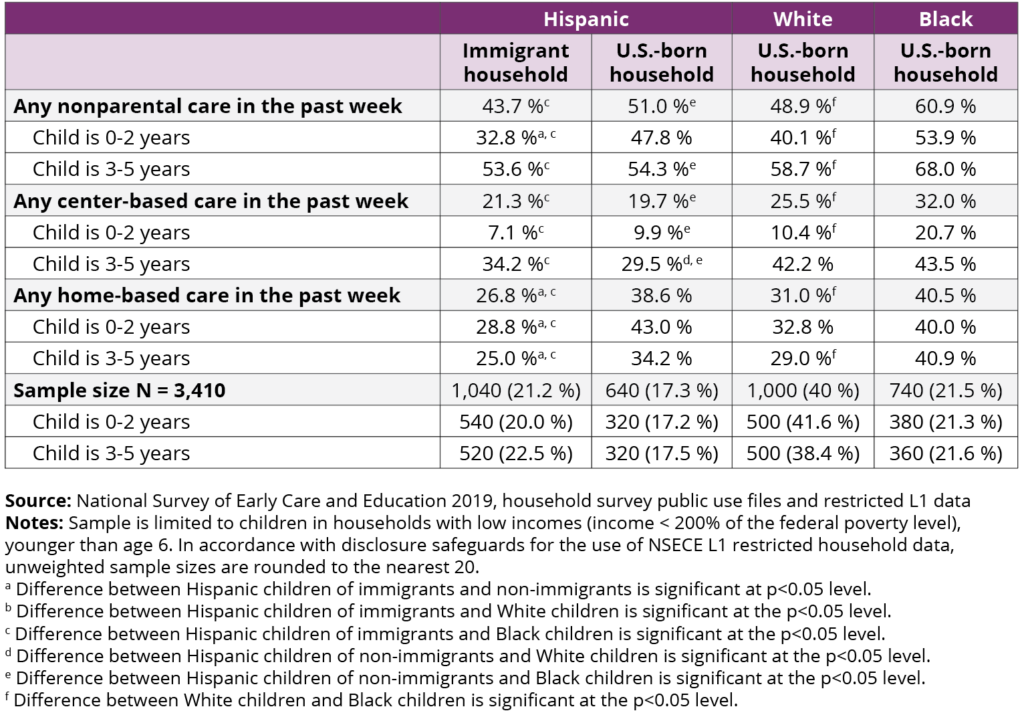

Table 1. ECE utilization by young children in households with low incomes, by child age, household nativity, and race and ethnicity, 2019

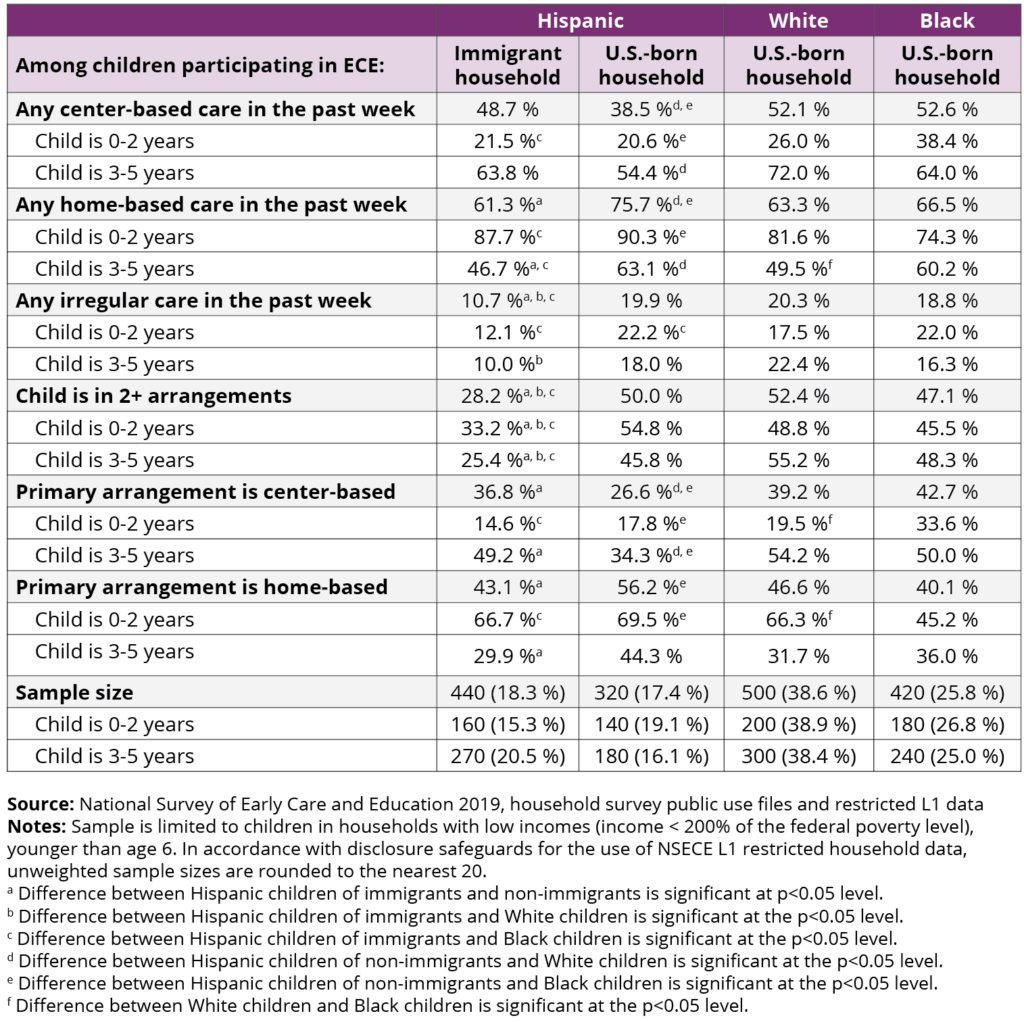

Table 2. Types of arrangements used by young children from households with low incomes in nonparental care, by household nativity, race and ethnicity, and child age, 2019

Table 3. Types of home-based arrangements used by young children in households with low incomes in nonparental care, by child age, household nativity and race and ethnicity, 2019

Footnotes

a We use “Hispanic” and “Latino” interchangeably throughout this report. The terms are used to reflect the U.S. Census definition to include individuals having origins in Mexico, Puerto Rico, and Cuba, as well as other “Hispanic, Latino or Spanish” origins.

b The NSECE is a repeated cross-sectional study (2012, 2019 and, soon to be collected, in 2024). Comparisons between the 2012 and 2019 are not longitudinal.

c These estimates represent the share of children from households with low incomes who were in any ECE arrangement.

d Children in parental care only were excluded from this analysis.

e Additional detail on these analyses are available from the authors.

f A small share of 6-year-olds in the 2019 NSECE were identified as not being in kindergarten, which may reflect birthdates after the eligibility cutoff or parental decisions to delay kindergarten entry. In this brief, we limit our analysis to children younger than age 6, which is comparable to the broader early childhood literature that has focused on children from birth through age 5.

g This sample is representative of approximately 8,497,114 children from birth to age 6, not yet in kindergarten, who live in households with low incomes. In accordance with disclosure safeguards for the use of NSECE L1 restricted household data, unweighted sample sizes are rounded to the nearest 20.

Suggested Citation

Mendez, J., Crosby, D., & Stephens, C. (2024). Nearly half of Hispanic children in households with low incomes used early care and education in 2019. National Research Center on Hispanic Children & Families. DOI:10.59377/349u4419b

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to thank the Steering Committee of the National Research Center on Hispanic Children & Families—along with Sara Amadon, Kristen Harper, Laura Ramirez, and Ana Maria Pavic—for their helpful comments, edits, and research assistance at multiple stages of this project. The Center’s Steering Committee is made up of the Center investigators—Drs. Natasha Cabrera (University of Maryland, Co-I), Danielle Crosby (University of North Carolina at Greensboro, Co-I), Lisa Gennetian (Duke University; Co-I), Lina Guzman (Child Trends, PI), Julie Mendez (University of North Carolina at Greensboro, Co-I), and Maria Ramos-Olazagasti (Child Trends, Deputy Director and Building Capacity lead)—and federal project officers Drs. Ann Rivera, Jenessa Malin, and Kimberly Clum (Office of Planning, Research and Evaluation), and Dr. Shirley Huang (Society for Research in Child Development Policy Fellow, Office of Planning, Research and Evaluation).

Editor: Brent Franklin

Designers: Catherine Nichols & Joseph Boven

About the Authors

Julia Mendez, PhD, is a co-investigator of the National Research Center on Hispanic Children & Families, co-leading the research area on early care and education. She is a professor in the Department of Psychology at the University of North Carolina at Greensboro. Her research focuses on risk and resilience among ethnically diverse children and families, with an emphasis on parent-child interactions and family engagement in early care and education programs.

Danielle Crosby, PhD, is a co-investigator of the National Research Center on Hispanic Children & Families, co-leading the research area on early care and education. She is an associate professor in the Department of Human Development and Family Studies at the University of North Carolina at Greensboro. Her research focuses on understanding how policies and systems shape early education access and quality for young children in low-income families.

Christina Stephens, PhD, was a predoctoral fellow of the National Research Center on Hispanic Children & Families, in the research area on early care and education. She is now a postdoctoral research associate at the University of Virginia with the Education Science Training Program on English Learners (EL-VEST). Her research focuses on understanding the factors and policies that promote child care access and quality, particularly among low-income families with young children.

About the Center

The National Research Center on Hispanic Children & Families (Center) is a hub of research to help programs and policy better serve low-income Hispanics across three priority areas: poverty reduction and economic self-sufficiency, healthy marriage and responsible fatherhood, and early care and education. The Center is led by Child Trends, in partnership with Duke University, University of North Carolina at Greensboro, and University of Maryland, College Park. This publication was made possible by Grant Number 90PH0028 from the Office of Planning, Research and Evaluation, Administration for Children and Families, U.S. Department of Health and Human Services. Its contents are solely the responsibility of the authors and do not necessarily represent the official views of the Office of Planning, Research and Evaluation, the Administration for Children and Families, or the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services.

Copyright 2024 National Research Center on Hispanic Children & Families

References

1 Weiland, C., & Yoshikawa, H. (2013). Impacts of a prekindergarten program on children’s mathematics, language, literacy, executive function, and emotional skills. Child Development, 84(6), 2112–2130. https://doi.org/10.1111/cdev.12099

2 Crosby, D., & Mendez, J. (2017). How common are nonstandard work schedules among low-income Hispanic households with young children? National Research Center on Hispanic Children and Families. https://www.hispanicresearchcenter.org/research-resources/how-common-are-nonstandard-work-schedules-among-low-income-hispanic-parents-of-young-children/

3 Ferreira van Leer, K., Crosby, D., & Mendez, J. (2021). Disruptions to Child Care Arrangements and Work Schedules for Low-Income Hispanic Families are Common and Costly. National Research Center on Hispanic Children & Families. www.hispanicresearchcenter.org/research-resources/disruptions-to-child-care-arrangements-and-work-schedules-for-low-income-hispanic-families-are-common-and-costly

4 Kids Count Data Center. (2023). Child Population by Race and Ethnicity in United States. The Annie E. Casey Foundation. https://datacenter.aecf.org/data/tables/103-child-population-by-race-and-ethnicity?loc=1&loct=2#detailed/2/2-52/false/2048,574,1729,37,871,870,573,869,36,868/12/423,424

5 Crosby, D., Stephens, C. & Mendez, J. (2023). Many Hispanic Households With Low Income Access No-Cost or Low-Cost Care, Yet Nearly One in Four Face High Out-of-Pocket Costs. National Research Center on Hispanic Children & Families. https://doi.org/10.59377/768o8919u

6 Hill, Z., Gennetian, L.A., & Mendez, J. (2019). A descriptive profile of state Child Care and Development Fund policies in states with high populations of low-income Hispanic children. Early Childhood Research Quarterly, 47, 111-123. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ecresq.2018.10.003

7 Lin, Y., Crosby, D., Mendez, J., & Stephens, C. (2022). Child care subsidy staff share perspectives on administrative burden faced by Latino applicants in North Carolina. National Research Center on Hispanic Children & Families. https://www.hispanicresearchcenter.org/wp-content/uploads/2022/08/HC-NC-CCDF-brief_FINAL.pdf

8 NSECE Project Team (National Opinion Research Center). (2021). National Survey of Early Care and Education (NSECE), [United States], 2019. Inter-university Consortium for Political and Social Research [distributor]. https://doi.org/10.3886/ICPSR37941.v3

9 Zero to Three. (2021). Infant-Toddler Child Care Fact Sheet. https://www.zerotothree.org/resource/infant-toddler-child-care-fact-sheet/

10 Administration for Children and Families, Office of Child Care (n.d.) Informal In-Home Child Care. ChildCare.gov. https://childcare.gov/consumer-education/informal-in-home-child-care

11 Adams, G., & Pratt, E. (2021). Assessing Child Care Subsidies through an Equity Lens: A Review of Policies and Practices in the Child Care and Development Fund. Urban Institute. https://www.urban.org/sites/default/files/publication/104777/assessing-child-care-subsidies-through-an-equity-lens.pdf

12 Bromer, J., Porter, T., Jones, C., Ragonese-Barnes, M., & Orland, J. (2021). Quality in Home- Based Child Care: A Review of Selected Literature, OPRE Report # 2021-136, Washington, DC: Office of Planning, Research, and Evaluation, Administration for Children and Families, U.S. Department of Health and Human Services. https://www.acf.hhs.gov/sites/default/files/documents/opre/HBCCSQ_LiteratureReview_2021-Remediated.pdf

13 Stephens, C., Crosby, D., & Mendez, J. (2023). Early Care and Education Providers Vary in Their Availability and Flexibility to Meet Hispanic Families’ Needs. National Research Center on Hispanic Children & Families. https://doi.org/10.59377/658l3776v

14 Chen, Y., Ferreira Van Leer, K., & Guzman, L. (2021). Many Latino and Black Households Made Costly Work Adjustments in Spring 2021 to Accommodate COVID-Related Child Care Disruptions. National Research Center on Hispanic Children & Families. https://www.hispanicresearchcenter.org/research-resources/many-latino-and-black-households-made-costly-work-adjustments-in-spring-2021-to-accommodate-covid-related-child-care-disruptions/

15 Lee, E. K., & Parolin, Z. (2021). The care burden during COVID-19: A national database of child care closures in the United States. Socius,7, 1-10. https://doi.org/10.1177/23780231211032028

16 Rodriguez-Diaz, C. E., Guilamo-Ramos, V., Mena, L., Hall, E., Honermann, B., Crowley, J. S., Millett, G. A., Prado, G. J., Marzan-Rodriguez, M., Beyrer, C., Sullivan, P. S., & Millett, G. A. (2020). Risk for COVID-19 infection and death among Latinos in the United States: Examining heterogeneity in transmission dynamics. Annals of Epidemiology, 52, 46–53. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.annepidem.2020.07.007