Dec 6, 2023

Research Publication

Post-pandemic, Latino Parents With Low Incomes Remain Concentrated in Jobs Offering Few Workplace Flexibilities

Authors:

Introduction

The COVID-19 pandemic created enormous disruptions to Americans’ work lives—especially for Latinoa workers, who had among the highest pandemic-related unemployment rates.1 Hispanic workers are overrepresented in the low-wage industries and occupations that were hard-hit by pandemic-related business closures and disruptions.2-7 Additionally, even as demand for labor improved during the post-pandemic recovery, Latino parents, and mothers in particular, were disproportionately impacted by closures and other disruptions in child care and schooling. These challenges were compounded for Latino parents who, even pre-pandemic, were overrepresented in industries and occupations with fewer employer-provided benefits and flexibilities to effectively navigate these child care disruptions.7-11

In this brief, we provide the first national portrait of the industries and occupations that employ Latino parents with low incomes in the aftermath of the pandemic, and highlight employment shifts that occurred during the pandemic. We use national data from two sources (the Current Population Survey [CPS] and the newly collected Business Response Survey [BRS]) to detail (1) the industries (defined as the type of business conducted by a persons’ employer) and occupations (defined as the type of work a person does on their job) in which Latino parents worked pre- and post-pandemic; and (2) how the benefits and work schedule flexibilities offered by businesses in these industries—sick leave, paid time off for dependent care, work schedule changes, and the availability of remote work—changed (or not) in response to the pandemic. We then discuss the implication of these findings for Latino parents’ child care needs—and their ability to respond to care disruptions in ways that limit their impact on family and economic well-being—and for the human service programs that aim to support family economic well-being and child care needs. Human service programs that support families—including those that provide child care supports—primarily serve families with low incomes, so we focus on Latino parents in households earning less than 200 percent of the poverty threshold.

Latino parents are a growing and critical segment of the labor market.8,12 The COVID-19 pandemic—and the policies put in place to mitigate its effects—had substantial employment consequences, especially in the industries and occupations that employed the vast majority of Latino parents with low incomes at the onset of the pandemic. For example, the leisure and hospitality industries were among the most affected, experiencing employment losses of up to 47 percent.1 Other industries that experienced large pandemic-related employment declines include retail, manufacturing, other services, construction, warehousing, social assistance (especially child care workers), health services (due to closures of the offices of physicians and other health practitioners), and education.1 While employment in these industries has largely rebounded to pre-pandemic levels, it is important to examine whether Latino parents with low incomes continue to work in these industries post-pandemic. Knowing this provides context to understand the implications of pandemic-induced changes in employer-provided benefits and flexibilities on parents’ ability to secure child care and cope with child care disruptions.

Key Findings

Relative to before the COVID-19 pandemic, Latino mothers and fathers with low incomes remain disproportionately concentrated in select industries and occupations, such as construction, accommodation and food services, and personal care and service—with one exception.

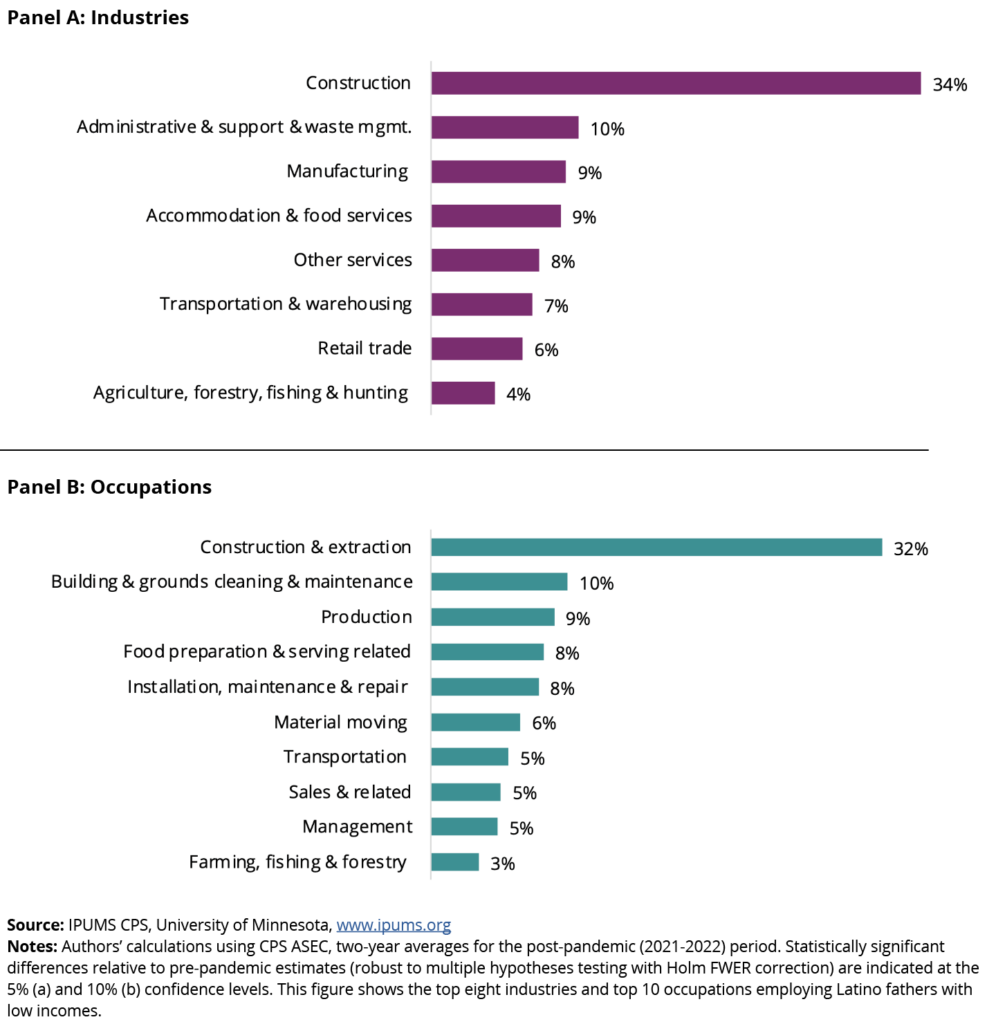

- Post-pandemic, nearly 90 percent of Latino fathers with low incomes worked in one of eight industries. More than one third worked in the construction industry alone (along with its parallel occupations).

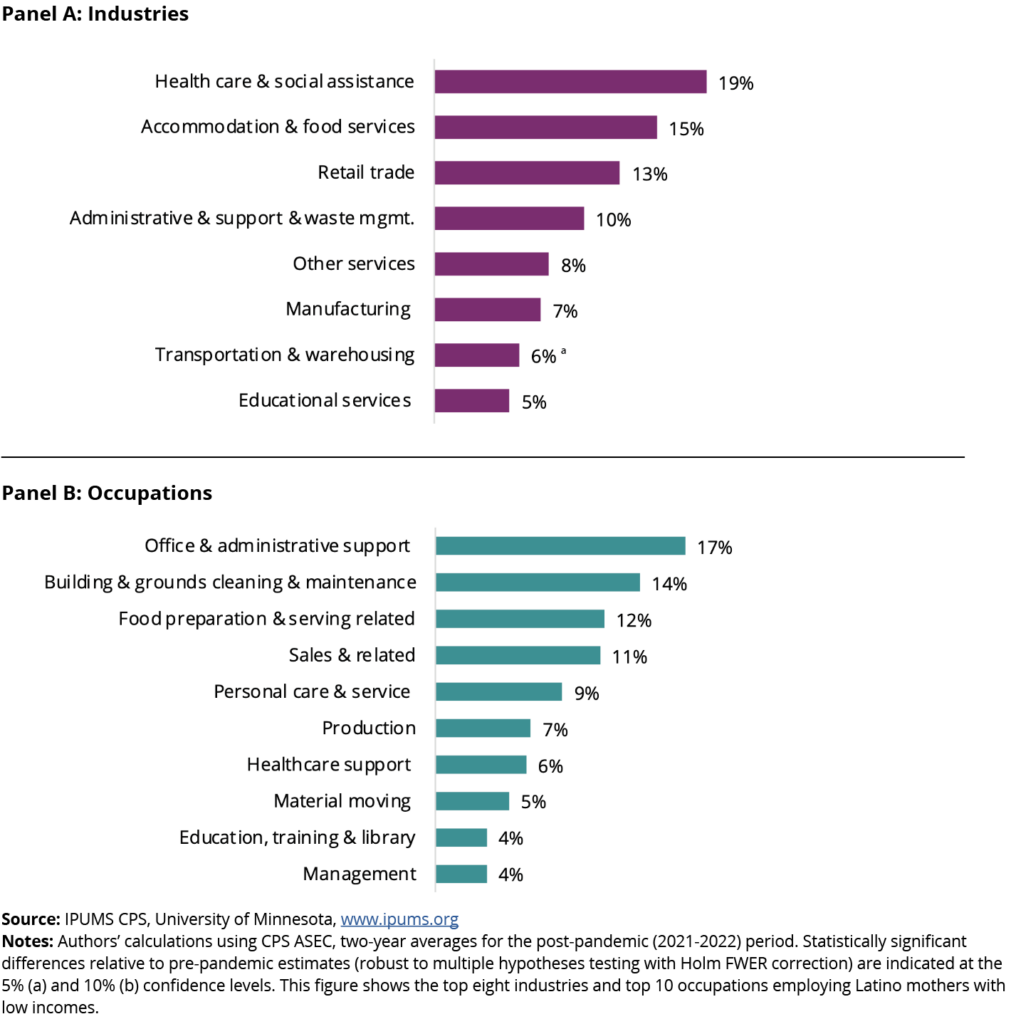

- Post-pandemic, more than half of Latina mothers with low incomes worked in one of four industries: health care and social assistance, accommodation and food services, retail trade, and administrative and support and waste management. In a notable shift, the percentage of Latina mothers working in the warehousing and transportation industry nearly tripled from 2019 to 2022, from 2 to nearly 6 percent.

In response to the pandemic, the industries that employ many Latino parents with low incomes were among the least likely to initiate or expand benefits and flexibilities—such as sick leave, paid time off, work schedule flexibilities, and telework—that allow families to respond to child care disruptions with limited negative impacts (e.g., loss of income). For example:

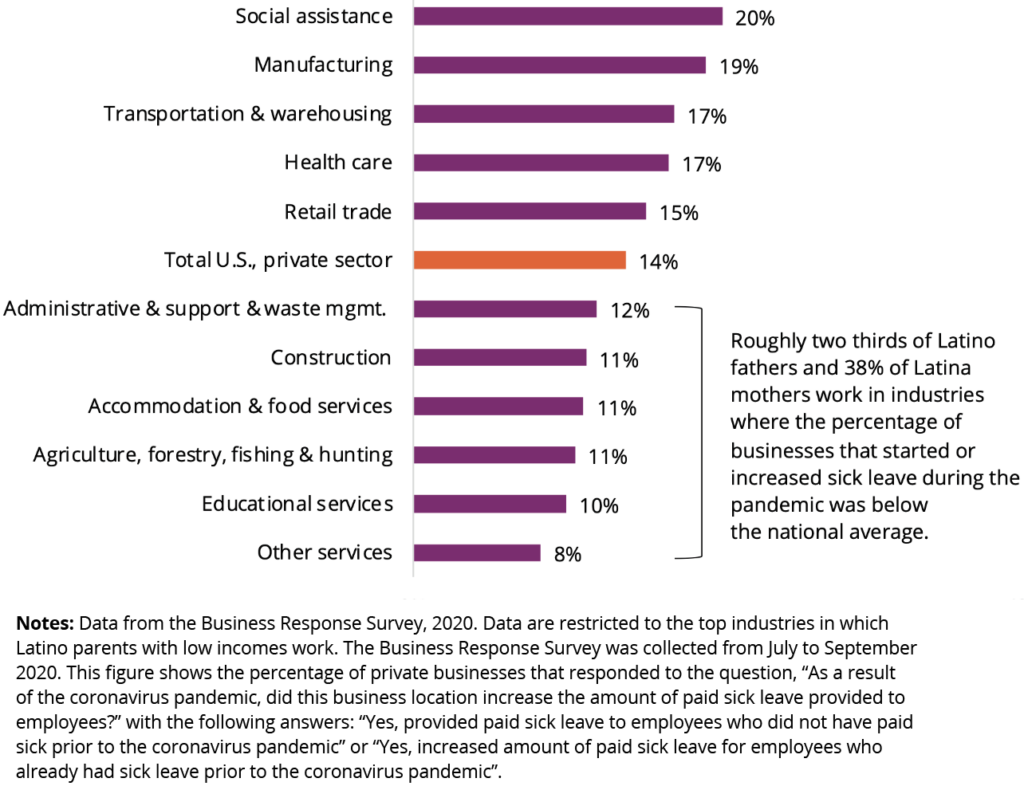

- Two thirds (66%) of Latino fathers with low incomes and 38 percent of Latina mothers with low incomes work in industries in which the percentage of businesses that started or increased sick leave during the pandemic was lower than the national average.

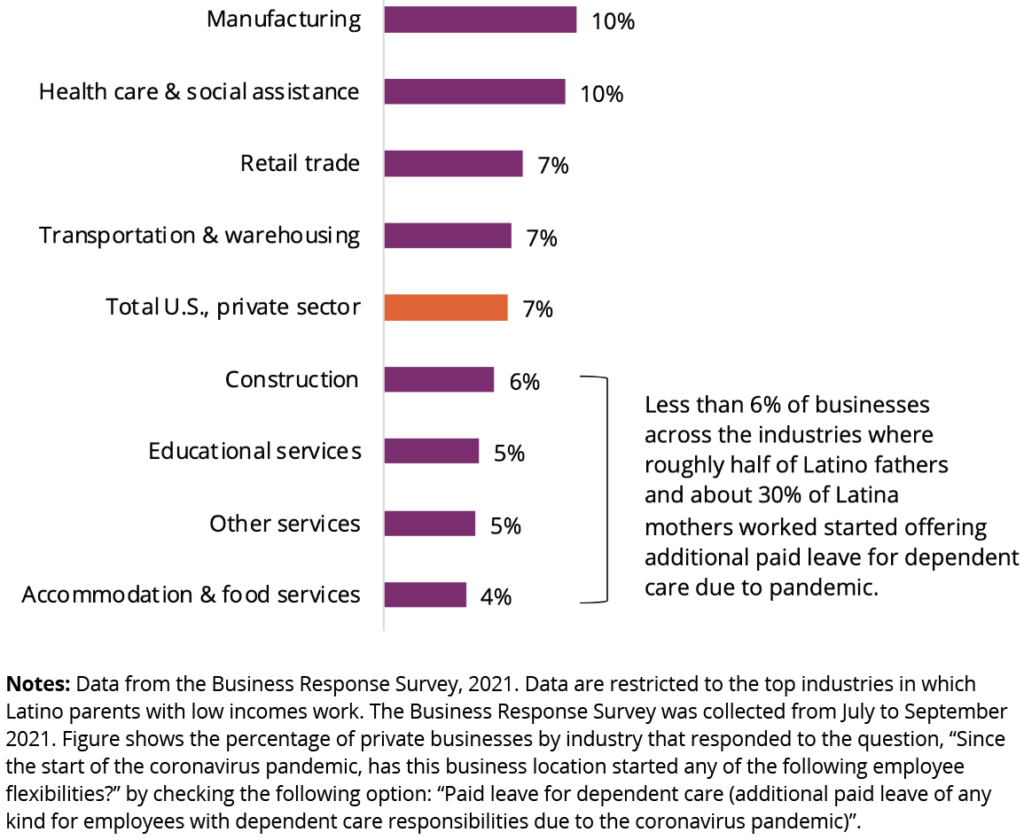

- Less than 6 percent of businesses across the industries that employ roughly half (51%) of Latino fathers with low incomes and about 30 percent of Latina mothers with low incomes started or extended their provisions for paid leave for dependent care due to the pandemic.

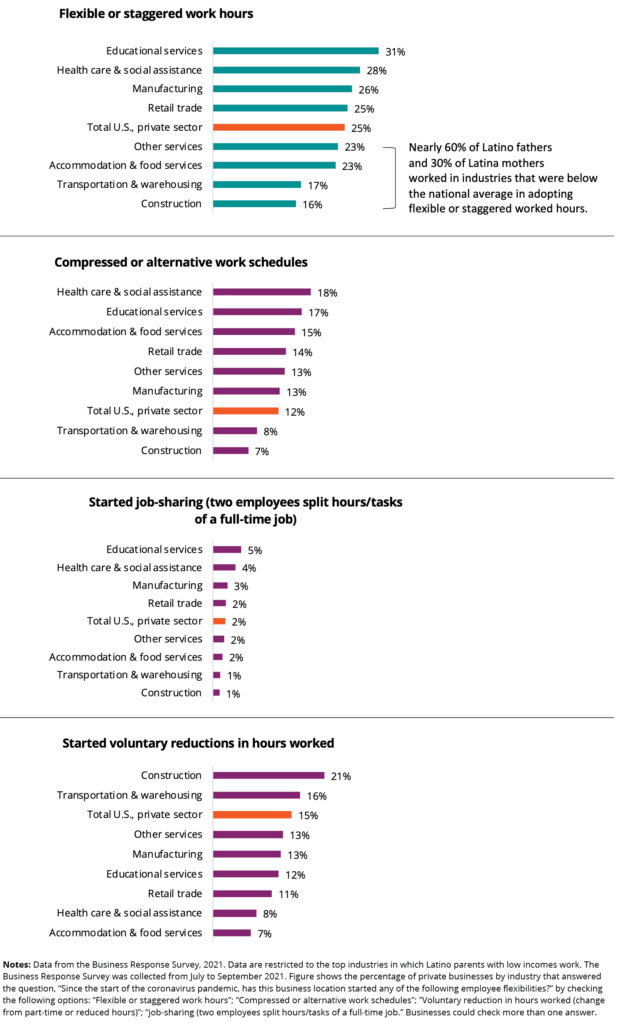

- Nearly 60 percent of Latino fathers with low incomes and 30 percent of Latina mothers with low incomes work in industries that were less likely than the national average (25% of businesses) to start or extend the availability of flexible or staggered work hours.

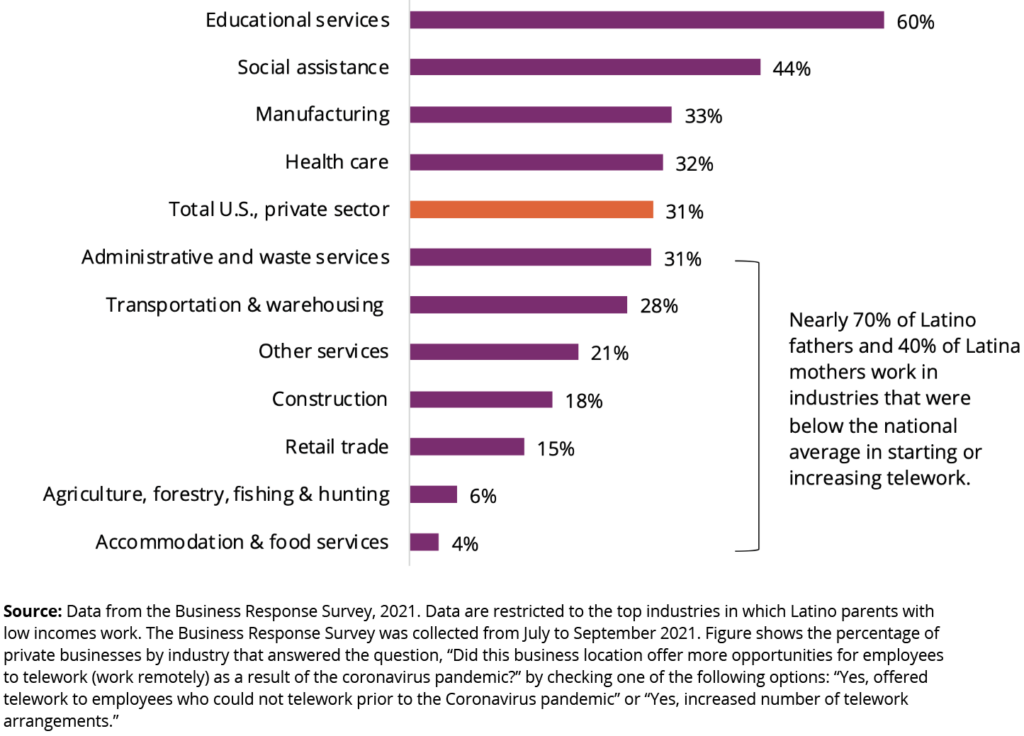

- Almost 70 percent of Latino fathers with low incomes and 40 percent of Latina mothers with low incomes work in industries that were below the national average in starting or increasing telework during the pandemic.

Post-pandemic, the gap in access to employer-provided benefits and flexibilities between Latino parents with low incomes and parents who work in other occupations and industries may be wider than before the pandemic. This is because the industries that employ Latino parents with low incomes were among the least likely to institute pandemic-era expansions of workplace benefits and flexibilities. And because child care disruptions have become more frequent—due in part to the negative impact of the pandemic on the child care sector, and to the existing inequities and large-scale disinvestment in the child care industry that were present pre-pandemic—the concentration of Latino parents with low incomes in industries and occupations that offer limited flexibility to respond to interruptions will continue to negatively affect their economic and family well-being.

Our findings suggest the need for federal-, state-, and employer-level interventions that address the lack of employment benefits and flexibilities that support child care needs and demands. In addition, job training programs and other human service programs for parents with low incomes should ensure that programs are accessible (e.g., eligibility determined by work hours) to parents whose employment status may be impacted by their child care needs.

Context: Employer-Provided Benefits and Flexibilities That Shape Child Care Options And Needs

Research finds that the characteristics of certain industries and occupations—such as schedule flexibility and predictability, the availability of sick leave or paid time off for dependent care, and the availability of remote work—can facilitate or hinder parents’ ability to find child care, respond to child care and schooling disruptions, and (more generally) meet their family needs.13 For example, parents who have little flexibility to control their own work schedules face more difficulty arranging formal child care.14,15 Their challenges can include the need to find child care options that are open very early in the morning, after 5:00 pm, or on weekends. According to some estimates, only 8 percent of center-based child care providers and about one third (34%) of home-based providers offer child care that is open during nontraditional hours.16 As a result, workers with variable hours may rely on various types of child care arrangements to meet their needs—potentially combining formal care arrangements (e.g., center-based) with other forms of care and establishing child care arrangements on an ad hoc basis.17-19 In addition, parents who lack employer-provided benefits (such as paid leave) or flexibilities (like remote work) may be less able to cope with child care or school disruptions; they may need to miss work or leave work early, cut their hours, use unpaid leave, and lose pay when their child care arrangement is unavailable.13,20

Latino parents’ abilities to meet their family and child care needs may be particularly vulnerable to a lack of employer-provided benefits and flexibilities. Historically and currently, Latino parents tend to be overrepresented in industries and occupations that lack benefits and offer little flexibility, and in which schedule instability, unpredictability, and lack of remote work options are common.7,9,18,21-30

Findings: Industries and Occupations Employing Latino Parents With Low Incomes, Post- Pandemic

In this section, we present findings from our analysis of the 2019-2020 (pre-pandemic) and the 2021-2022 (post-pandemic) Current Population Survey (CPS), detailing the industries and occupations in which most Latino fathers (Figure 1) and mothers (Figure 2) with low incomes work post-pandemic. Because there were few pre- to post-pandemic shifts in the industries and occupations in which Latino parents with low incomes work, we focus our findings on the post-pandemic period, noting the few cases where we observed statistically significant changes. Pre-pandemic distributions are shown in appendix A.

Latino fathers with low incomes

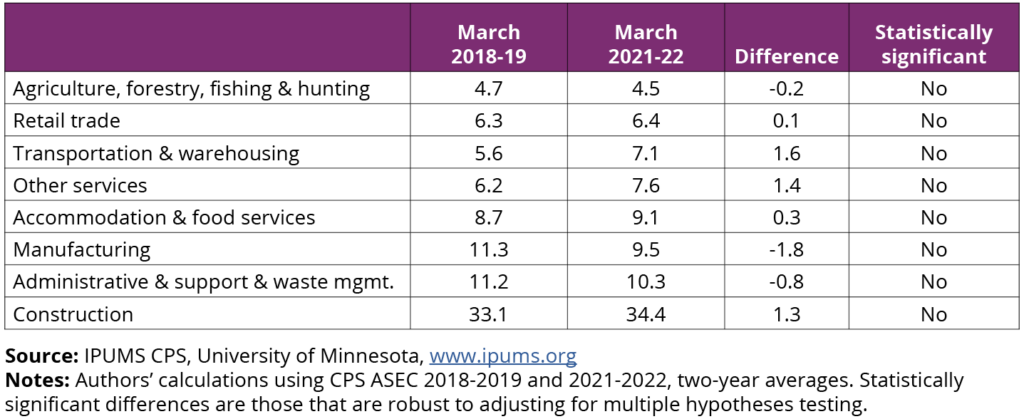

Post-pandemic, employed Latino fathers with low incomes are concentrated in eight industries: construction (34%); manufacturing (9.5%); administrative and support and waste management (10%); accommodation and food services (9%); transportation and warehousing (7%); retail trade (6%); agriculture, forestry, fishing, and hunting (4.5%); and other services (8%). Overall, 88 percent of Latino fathers with low incomes work in these industries (see Figure 1, Panel A).

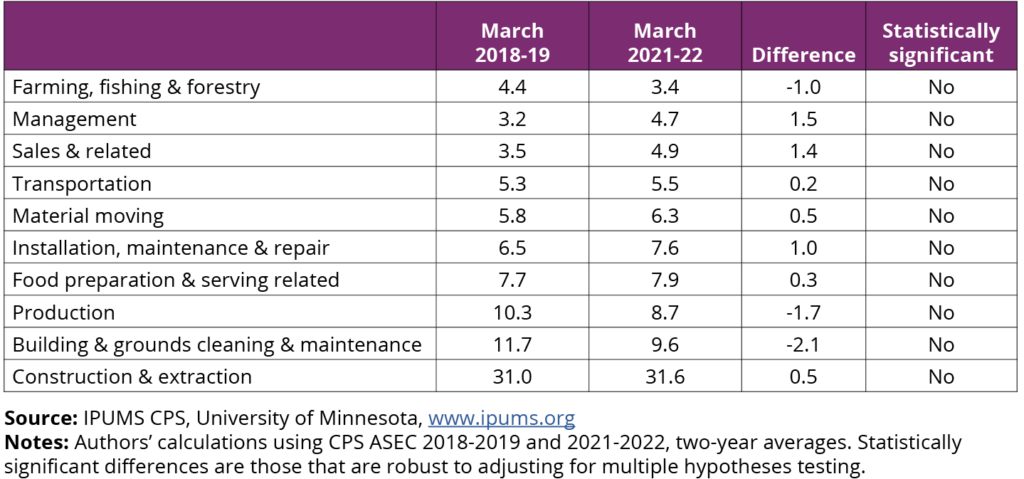

The top 10 occupations of Latino fathers with low incomes align with these industries. Post-pandemic, nearly one third of Latino fathers with low incomes work in construction and extraction occupations (32%), followed by those in building cleaning and maintenance occupations (10%); production (9%); food preparation and serving-related (8%); material moving (6%); transportation (6%); installation, maintenance, and repair (8%); farming, fishing, and forestry (3%); sales and related (5%); and management (5%) (see Figure 1, Panel B).

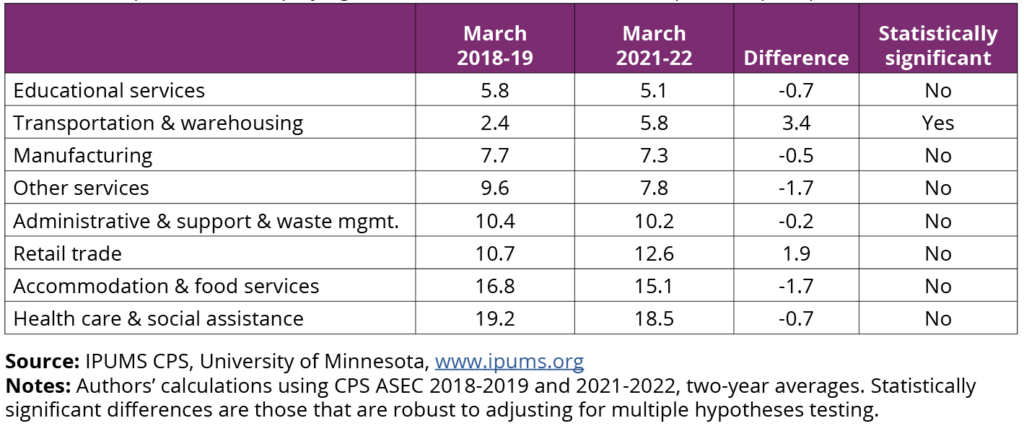

Overall, the industries and occupations that employ Latino fathers with low incomes post-pandemic are similar to those from the pre-pandemic period (see appendix A for pre-pandemic distributions).

Figure 1: Post-pandemic, one third of Latino fathers with low incomes work in the construction industry and construction-related occupations

Post-pandemic distribution of the industries and occupations employing Latino fathers with low incomes, two-year average for 2021-2022

Latina mothers with low incomes

Post-pandemic, employed Latina mothers with low incomes are concentrated in eight industries: health care and social assistance (19%), accommodation and food services (15%), retail trade (13%), administrative and support and waste management (10%), other services (8%), manufacturing (7%), transportation and warehousing (6%), and educational services (5%). Approximately 80 percent of Latina mothers with low incomes work in these industries (see Figure 2, Panel A).

The top 10 occupations of employed Latina mothers with low incomes included office and administrative support (17%); building and grounds cleaning and maintenance (14%); food preparation and serving-related (13%); sales and related (11%); personal care and service (9%); production (7%); health care support (6%); material moving (5%); education, training, and library (4%); and management (4%) (see Figure 2, Panel B).

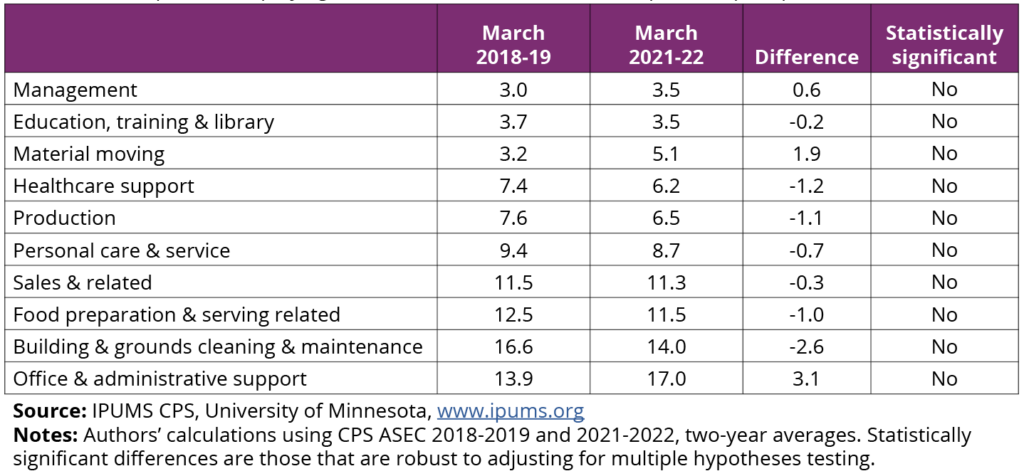

In general, the industries that employ Latina mothers with low incomes post-pandemic are similar to those from the pre-pandemic period, with the exception of the warehousing and transportation industry. The percentage of Latina mothers in this industry nearly tripled from 2019 to 2022, from 2 percent to nearly 6 percent. Post-pandemic, while most Latina mothers with low incomes work in similar occupations to those from the pre-pandemic period, the office and administrative support occupation surpassed building and grounds cleaning and maintenance to employ the highest percentage of Latina mothers with low incomes (see appendix A for pre-pandemic distributions).

Figure 2: Post-pandemic, Latina mothers with low incomes are most likely to work in the health care and social assistance industry

Post-pandemic distribution of the industries and occupations employing Latina mothers with low incomes, two-year average for 2021-2022

COUNTRY OF BIRTH AND THE INDUSTRY AND OCCUPATIONAL DISTRIBUTION OF LATINO PARENTS

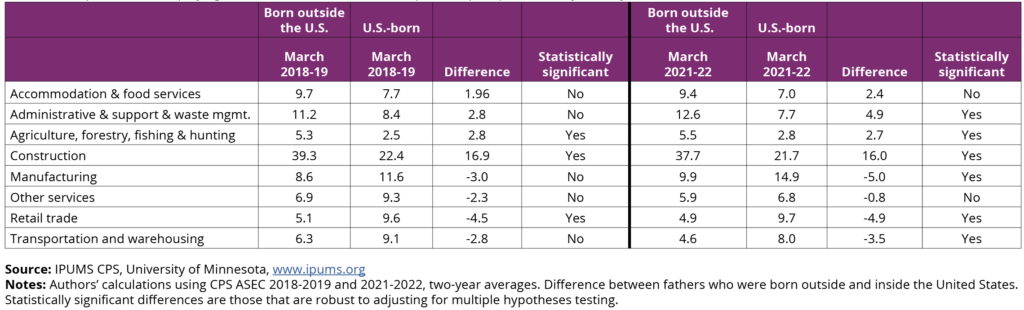

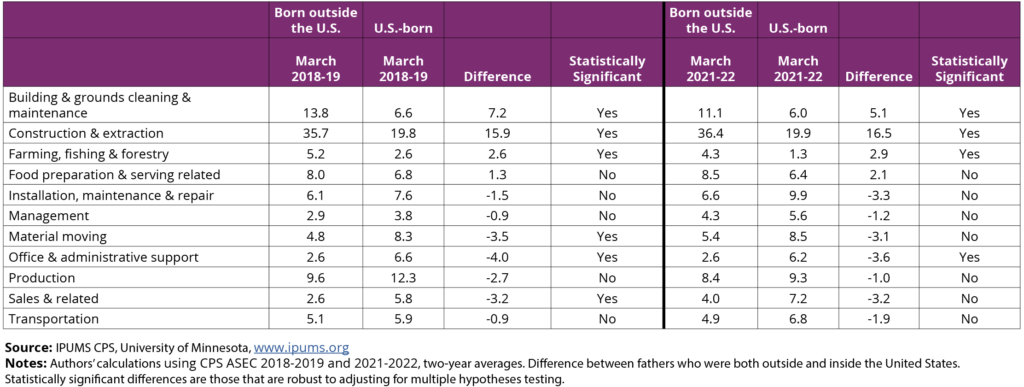

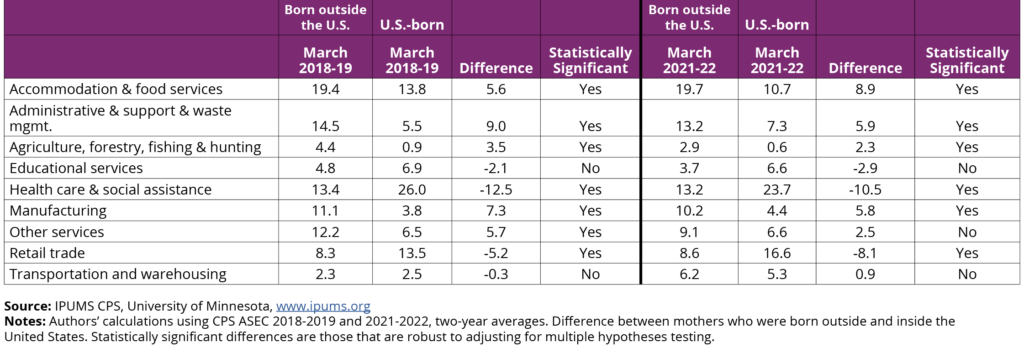

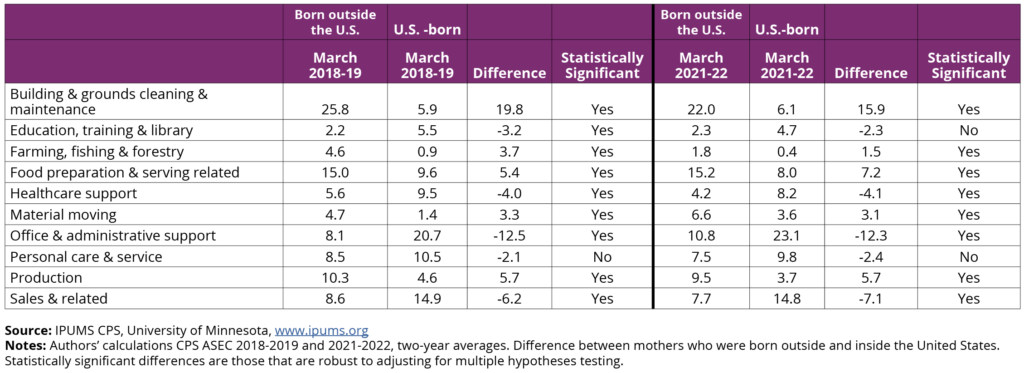

Latino parents born outside of the United States face greater barriers to employment—a fact that, pre-pandemic, increased their overrepresentation in low-wage and low-job-quality industries and occupations relative to their U.S.-born counterparts. Our analysis shows that, post-pandemic, the industry and occupational distribution of Latino parents with low incomes born outside the United States continues to differ from those who are U.S.-born (and remain largely unchanged from the pre-pandemic period, see Appendix B).

FATHERS. Post-pandemic, Latino fathers with low incomes born outside the United States are much more likely than U.S.-born fathers to work in the construction industry (38% vs 22%) and in construction and extraction occupations (36% vs 20%). A moderately higher share of those born outside the United States (relative to their U.S.-born counterparts) work in building and grounds cleaning and maintenance; farming, fishing, and forestry; and food preparation and related occupations; however, these differences are smaller (from 3 to 5 percentage points).

MOTHERS. Post-pandemic, Latina mothers with low incomes born outside the United States are much more likely than their U.S.-born counterparts to work in building cleaning and maintenance occupations (22% vs 6%). They are also more likely to work in the accommodation and food services industry (20% vs 11%), the administrative and support and waste management industry (13% vs 7%), and in the manufacturing industry (10% vs 4%). Conversely, higher shares of U.S.-born mothers work in office and administrative support occupations (23% vs 11%) and sales and related occupations (15% vs 8%).

Post-Covid Changes in Employer-Provided Benefits and Flexibilities That Shape Child Care Options and Needs Among Latino Parents With Low Incomes

In response to the pandemic, many industries provided more employer-sponsored benefits and adopted more flexible policies; if they remain in place, such offerings might better support parents’ child care options and needs moving forward. We analyzed data from the 2020 and 2021 Business Response Survey (BRS) to explore how the industries that employ Latino parents with low incomes responded to the pandemic in terms of these benefits and flexibilities. The BRS is a new survey initiated by the Bureau of Labor Statistics (BLS) in 2020 to gather information about how the COVID-19 pandemic affected business operations. More generally, the BRS seeks to provide timely information about how the economy responds to various events.

Our analyses look at changes in benefits and flexibilities across industries in three domains: the availability of sick leave and paid time off, the flexibility of schedules, and the availability of remote work. Figures 3-6 show the percentage of business establishments within each industry that increased or started new practices across these domains. In interpreting these results, note that the publicly available data do not provide baseline or pre-pandemic information. When possible, we provide baseline numbers from other sources to help contextualize the BRS findings. Additionally, we show the national average included in all BRS tables to benchmark the results and to provide a comparison point for how the industries and occupations that employ Latino parents with low incomes deviate from this average.

Importantly, the specific industries included in the publicly available BRS estimates are not consistent across years and outcomes examined. For example, some BRS tables combine the health care and social assistance industries while others show them separately. Similarly, administrative and support; waste management; and agriculture, forestry, and fishing are not shown in all BRS tables. Thus, the industries included in Figures 3-6 are not always consistent.

Sick leave and paid time off

Figure 3 shows the percentage of business establishments within each industry that started providing sick leave during the pandemic, or that increased the amount of sick leave provided. We know from prior research that, pre-pandemic, the majority of private sector workers had access to sick leave (73%),31 although this percentage varies among the industries that employ Latino parents with low incomes. For example, at the higher end, 84 percent of workers in the education and health services industries and 79 percent of those in manufacturing and transportation had sick leave in 2019. At the lower end, only 45 percent of employees in the food services industry had pre-pandemic sick leave. For the other industries in which Latino parents with low incomes work—such as construction, administrative and support and waste management, other services, and retail trade—this percentage ranged from 58 to 65 percent, respectively.32

As shown in Figure 3, the majority of businesses in the industries that employ Latino parents with low incomes did not start or increase sick leave in response to the pandemic. However, of those that did, social assistance (20%), manufacturing (19%), transportation and warehousing (17%), health care (17%), and retail trade (15%) industry businesses did so at a rate higher than the national average (of 14%). Post-pandemic, nearly one quarter (23%) of Latino fathers with low incomes and roughly 40 percent of Latina mothers with low incomes work across these industries. With the exception of retail trade, these are also the industries that, pre-pandemic, were above the national average in the percentage of workers with access to sick leave. However, most Latino parents with low incomes are employed in the remaining industries, which were below the national average in the likelihood of starting or expanding sick leave in response to COVID.

Figure 3: Most businesses within the industries that employ Latino parents with low incomes did not start or increase sick leave during the pandemic

Distribution of the percent of business establishments that started or increased sick leave, by the top industries employing Latino parents with low incomes, 2020

Figure 4 shows the percentage of private businesses by industry that started providing additional paid leave for dependent care (either at all or in addition to what was already in place) because of the pandemic. Prior to the pandemic, in 2017-2018, 66 percent of workers had access to paid leave of any kind (e.g., personal, medical, family care, etc.), although this percentage was lower for workers in construction and service occupations (36% and 43%, respectively).33 Very few businesses across the industries that employ Latino parents with low incomes initiated paid leave for dependent care due to the pandemic (see Figure 4). Approximately 10 percent of businesses in the manufacturing and social assistance and health care industries started additional paid leave for dependent care, which is higher than the national average (6.5%). About one quarter (26%) of Latina mothers with low incomes and 9.5 percent of Latino fathers with low incomes work in these industries. However, less than 6 percent of businesses across the other industries—those that employ roughly half (51%) of Latino fathers with low incomes and 30 percent of Latina mothers with low incomes—started this benefit, including only 4 percent of businesses in the accommodation and food services industry.

Figure 4: Most businesses within the industries that employ Latino parents with low incomes did not start providing additional paid leave for dependent care as a result of the pandemic

Distribution of the percent of business establishments that offered additional paid leave for dependent care, by the top industries employing Latino parents with low incomes, 2021

Work schedule flexibility

The COVID-19 pandemic led some businesses across industries to adopt new policies around work arrangements and schedules that may allow for more employee flexibility or control—via job sharing, voluntary reduction in work hours, compressed or alternative work schedules, and flexible or staggered work hours. This type of flexibility was generally quite rare pre-pandemic. Data show that roughly 11 percent of private sector workers had a flexible schedule pre-pandemic, and that this offering was generally lowest in many of the industries that employ the majority of Latino parents with low incomes (e.g., administrative and waste management services, retail, construction, and accommodation and food services).34

As shown in Figure 5, the most adopted schedule flexibility was the implementation of flexible or staggered work hours, although this varied across industries. Nearly one third (31%) of businesses in the educational services industry started this practice, compared to only 16 percent of businesses in the construction and transportation-warehousing industries. Post-pandemic, roughly 40 percent of Latino fathers work across these industries. For businesses in the other industries that employ many Latino parents with low incomes, the adoption of flexible work arrangements or staggered work hours was similar to the national average (24.6%).

Voluntary reductions in work hours and compressed/alternative work schedules were the next most frequent schedule flexibilities adopted in response to the pandemic. These changes were adopted by 13 to 20 percent of businesses in the industries that employ Latino parents with low incomes—somewhat higher than the national average. However, the transportation-warehousing and construction industries—employing over 40 percent of Latino fathers with low incomes and nearly 6 percent of Latina mothers with low incomes—were below the national average in adopting this flexibility.

Job sharing was a very rare practice across the industries that employ most Latino parents with low incomes—just 1 to 5 percent of businesses in these industries started this practice. At the high end, 5 percent of businesses in the accommodation-food services industry implemented job sharing, which is higher than the national average of 2.6 percent. Notably, post-pandemic, this industry employs 9 percent of Latino fathers with low incomes and 17 percent of Latina mothers with low incomes.

Figure 5: The adoption of flexible or staggered work hours was the most common schedule flexibility adopted as a result of the pandemic

Distribution of the percent of business establishments that implemented flexible schedules, by the top industries employing Latino parents with low incomes, 2021

Telework

Prior to the pandemic, nearly 70 percent of Latino fathers and almost half of Latina mothers with low incomes worked in industries that did not offer telework options (<30% of businesses in these industries offered telework compared to nearly half of businesses across the private sector more broadly)—including accommodation and food services; agriculture, forestry, and fishing; retail trade; construction; and other services (BRS data not shown).

As shown in Figure 6, most businesses across these industries did not offer new telework or expand their telework opportunities as a result of the pandemic. Nationally, 30 percent of businesses started or increased telework arrangements during the pandemic. Businesses in educational services, social assistance, manufacturing, and health care were above the national average in providing this flexibility, ranging from 60 percent of businesses in educational services to 30 percent of businesses in administrative and support and waste management services. These industries employ roughly 10 percent of Latino fathers and 30 percent of Latina mothers with low incomes. However, only 4 percent of businesses in the accommodation and food services industry started or increased telework. This industry employs 9 percent of Latino fathers and 12 percent of Latina mothers with low incomes.

Figure 6: Most businesses in the industries that employ Latino parents with low incomes did not start to offer telework or change telework arrangements

Distribution of the percent of business establishments that started or increased telework arrangements, by the top industries employing Latino parents with low incomes, 2021

Conclusion

Our analysis presents the first national portrait of the industries and occupations that employ Latino parents with low incomes and how these shifted during the COVID-19 pandemic. We find that the majority of Latino parents with low incomes work in certain industries and occupations such as construction, accommodation and food services, and personal care and service, among others. This occupational segregation has been highlighted by other research and largely reflects persistent discrimination in hiring and other barriers that limit employment opportunities.4,6 Our analysis shows that the industry and occupational distribution of Latino parents with low incomes remains largely unchanged from pre- to post-pandemic for mothers and fathers, with one notable exception: A higher percentage of Latina mothers with low incomes work in the transportation and warehousing industry post-pandemic, relative to pre-pandemic.

In general, Latino parents with low incomes work in industries and occupations with limited employer-provided benefits (e.g., the ability to take sick or dependent care leave) and in which parents usually work nonstandard hours, have little control over their schedules, experience schedule instability, and are unable to work remotely.8,19,27 While the pandemic influenced some businesses across these industries to offer increased benefits and work schedule flexibilities, our analysis shows that, post-pandemic, the majority of businesses within the industries employing many Latino parents with low incomes have either not started offering benefits or have not increased benefits that allow parents to better meet family and child care needs. For example, the industries that were least likely to start additional paid leave for dependent care during the pandemic employ nearly one third of Latina mothers and almost half of Latino fathers with low incomes. Additionally, nearly 70 percent of Latino fathers and 40 percent of Latina mothers with low incomes work in industries that were below the national average in starting or increasing telework during the pandemic. To the extent that the broader business community increased or started job flexibilities, these changes—with few exceptions—did not take place in the industries employing most Latino parents with low incomes. This finding suggests that, following the pandemic, Latino workers with low incomes may have even less access to employer-provided benefits and flexibilities relative to other workers than they did pre-pandemic. Notably, Latino parents with low incomes born outside the United States are overrepresented in jobs that lack these flexibilities and benefits, including construction, accommodation and food services, and building and grounds cleaning and maintenance occupations.

Implications for child care

These findings have important implications for parents’ ability to find child care, particularly in the formal sector,8 and for their ability to respond to child care disruptions. Pre-pandemic, parents with low incomes already experienced frequent child care disruptions, including lack of availability or closures of child care arrangements, lack of affordability, or safety concerns.13 These disruptions have been exacerbated post-pandemic.13,20 After the onset of the pandemic, 30 to 40 percent of Latino households with children under age 12 reported child care disruptions. In Spring and Summer 2022—well into the recovery and roll-out of vaccinations—17 percent of Latino households reported child care disruptions.20 These disruptions are costly: Pre-pandemic estimates found that Latino parents with low incomes lost one week of wages per quarter, on average, due to child care disruptions.13

Indeed, other research indicates that many parents coped with child care disruptions by altering their work arrangements, missing work, cutting hours, or leaving the labor market. Post-pandemic, roughly one third of Latino parents responded to child care disruptions by cutting hours. Compared to all parents, Latino parents were less likely to use paid leave and to supervise their children while working as a way to cope with these disruptions.20 Some research, consistent with our own work, finds that Latino parents work in industries and occupations that do not provide leave or the option to telework. In supplementary analyses not shown in this brief, we found that, post-pandemic, roughly 9 percent of employed Latina mothers with low incomes who were absent from their job in the prior week missed work due to child care disruptions; pre-pandemic, this figure was 4 percent.

Implications for social service programs supporting child care needs

Our findings also have important implications for social services programs designed to support the child care needs of working parents with low incomes, including the Child Care and Development Fund (CCDF), which provides subsidies to states, territories, and tribes to administer child care programs for workers with low incomes. Research shows that parents who work in jobs with little flexibility and unstable, unpredictable, and nonstandard work schedules—such as the jobs held by many Latino parents with low incomes—are less likely to use child care subsidies than others.35 This occurs, in part, because these parents rely less on center-based care and more on family-based care or other informal care arrangements that offer flexibility and are available during nonstandard hours,35 even though attendance at center-based care is not required to receive subsidies.24,35,36 Additionally, features like unstable hours and forced part-time work, which may limit eligibility for child care subsidies, are more prevalent in the industries and occupations that employ Latino parents with low incomes.b,24,25,27,37 These limitations may even be exacerbated in the post-pandemic era if increased flexibilities—such as the voluntary work reductions adopted in the industries employing one third of Latino fathers and two thirds of Latina mothers with low incomes post-pandemic—put parents below state minimum work hour requirements. As a result of the pandemic, many state CCDF programs adapted their requirements (e.g., minimum hours and income limits). Future research should examine how these changes—coupled with changes in the job characteristics of Latino parents during the pandemic—shaped Latino parents’ subsidy eligibility and use.

The lack of benefits and flexibilities disproportionately experienced by Latino parents with low incomes might also negatively affect their participation and success in other important social service programs, including workforce training and education programs. Evidence from participants in the Health Profession Opportunity Grants (HPOG) Program—which offers training in health care professions for TANF recipients and other adults with low incomes—found that participants who are working parents or caregivers struggle to find child care options that are flexible, open during nontraditional hours, and allow them to fulfill their work and educational obligations. Findings from HPOG and other programs underscore that success for working parents and caregivers in this and similar training programs likely depends on having adequate support systems from family and friends and, importantly, on flexibility at work and school—which many occupations do not offer.38,39 As we show here, this lack of flexibility is particularly acute for Latino parents with low incomes.

Ultimately, while the pandemic did not substantially change the industry and occupational distribution of Latino parents with low incomes—or result in increased flexibility to support parents’ child care needs—it did negatively affect the child care industry, exacerbating child care disruptions.20 This is particularly problematic for Latino parents with low incomes, who continue to be concentrated in industries and occupations with limited flexibility to respond to family care needs and disruptions in their children’s care.

Future research should do more to understand how the post-pandemic work environment affects the child care choices available to Latino parents with incomes, their occupational choices, and how these may change in the future. Evidence suggests that employment of Latino parents with low incomes is, with some exceptions, expected to grow most across some of the industries and occupations that offer little flexibility.40 More research should also consider heterogeneity within the industries that employ Latino parents with low incomes—for example, it could consider the ways in which job quality, job characteristics, and the ability to cope with child care disruptions differ among workers who are unionized and those who are not. Finally, future research should focus on understanding how the job quality characteristics described in this study affect human service programs’ ability to serve parents with low incomes and what policy changes may be necessary to better achieve this goal.

Footnotes

a We use “Hispanic,” “Latino,” “Latinx,” and “Latine” interchangeably throughout the brief. The terms are used to reflect the U.S. Census definition to include individuals having origins in Mexico, Puerto Rico, and Cuba, as well as other “Hispanic, Latino or Spanish” origins.

b Because many parents with low incomes who have unstable or unpredictable work schedules often face varying hours and forced part-time work—where parents work fewer hours than desired—their eligibility for subsidies may depend on state guidelines regarding income limits and minimum work hours.25,37 For example, in 2020, nearly 40 percent of states had minimum work (or education) hour requirements for child care subsidies that ranged from a monthly average of 15 to 30 hours per week, although policies vary widely by subgroups (i.e., single parents, TANF recipients, foster parents) and across states. These numbers come from authors’ calculations using data from the Childcare and Development Fund Policies Database: https://ccdf.urban.org/search-database

Suggested Citation

Laurito, A., Wildsmith, E., & Guzman, L. (2023). Post-pandemic, Latino parents with low incomes remain concentrated in jobs offering few workplace flexibilities. National Research Center on Hispanic Children & Families. DOI: 10.59377/243y9056m

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to thank the Steering Committee of the National Research Center on Hispanic Children & Families—along with Pamela Joshi, Kristen Harper, James Fuller, and Laura Ramirez—for their helpful comments, edits, and research assistance at multiple stages of this project. The Center’s Steering Committee is made up of the Center investigators—Drs. Natasha Cabrera (University of Maryland, Co-I), Danielle Crosby (University of North Carolina at Greensboro, Co-I), Lisa Gennetian (Duke University; Co-I), Lina Guzman (Child Trends, PI), Julie Mendez (University of North Carolina at Greensboro, Co-I), and Maria Ramos-Olazagasti (Child Trends, Deputy Director and Building Capacity lead)—and federal project officers Drs. Ann Rivera, Jenessa Malin, and Kimberly Clum (Office of Planning, Research and Evaluation).

Editor: Brent Franklin

Designers: Catherine Nichols and Joseph Boven

About the Authors

Agustina Laurito, PhD, is an assistant professor in the Department of Public Policy, Management, and Analytics at the University of Illinois Chicago. She is a social policy researcher whose work examines how adverse social environments affect the wellbeing of children and families with a particular focus on immigrants in the U.S. Her work also seeks to identify policies, programs, and other factors that may help ameliorate the negative effects of adverse contexts.

Elizabeth Wildsmith, PhD, is a research scholar at Child Trends and has worked with the National Research Center on Hispanic Children & Families since 2013. She is a family demographer whose research examines the process of marriage, cohabitation, and childbearing, as well as how social and family contexts may increase exposure to, or offer protection from, risk factors associated with the negative health and well-being of women, children, and families.

Lina Guzman, PhD, is the principal investigator and director of the National Research Center on Hispanic Children & Families, where she oversees a broad research agenda; robust communication and capacity building activities, including efforts to build the pipeline of diverse scholars; and strategic partnerships with the research, policy, and practice community. She is vice president of strategy and strategic initiatives at Child Trends and serves as the director of the Child Trends Hispanic Institute. Her research focuses on describing the characteristics and experiences of diverse communities of Latinos living in the United States to help inform policies and programs.

About the Center

The National Research Center on Hispanic Children & Families (Center) is a hub of research to help programs and policy better serve low-income Hispanics across three priority areas: poverty reduction and economic self-sufficiency, healthy marriage and responsible fatherhood, and early care and education. The Center is led by Child Trends, in partnership with Duke University, University of North Carolina at Greensboro, and University of Maryland, College Park. The Center is supported by grant #90PH0028 from the Office of Planning, Research, and Evaluation within the Administration for Children and Families in the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services.

The National Research Center on Hispanic Children & Families is solely responsible for the contents of this brief, which do not necessarily represent the official views of the Office of Planning, Research, and Evaluation, the Administration for Children and Families, or the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services.

Copyright 2023 by the National Research Center on Hispanic Children & Families.

Appendix A

Table 1: Top industries employing Latino fathers with low incomes pre- and post-pandemic

Table 2: Occupations employing Latino fathers with low incomes pre- and post-pandemic.

Table 2: Occupations employing Latino fathers with low incomes pre- and post-pandemic.

Table 3: Top industries employing Latina mothers with low incomes pre- and post-pandemic

Table 3: Top industries employing Latina mothers with low incomes pre- and post-pandemic

Table 4: Occupations employing Latina mothers with low incomes pre- and post-pandemic

Appendix B

Table 1: Top industries employing Latino fathers with low incomes pre- and post-pandemic, by country of birth Table 2: Top 10 occupations employing Latino fathers with low incomes pre- and post-pandemic, by country of birth

Table 2: Top 10 occupations employing Latino fathers with low incomes pre- and post-pandemic, by country of birth

Table 3: Top industries employing Latina mothers with low incomes pre- and post-pandemic, by country of birth

Table 3: Top industries employing Latina mothers with low incomes pre- and post-pandemic, by country of birth

Table 4: Top 10 occupations employing Latina mothers with low incomes pre- and post-pandemic, by country of birth

Table 4: Top 10 occupations employing Latina mothers with low incomes pre- and post-pandemic, by country of birth

References

1Bureau of Labor Statistics. (2020). The Employment Situation – April 2020. U.S. Department of Labor. https://www.bls.gov/news.release/archives/empsit_05082020.htm

2Montenovo, L., Jiang, X., Lozano-Rojas, F., Schmutte, I., Simon, K., Weinberg, B., & Wing, C. (2022). Determinants in Disparities in Early COVID-19 Job Losses. Demography, 59(3), 827–855. https://doi.org/10.1215/00703370-9961471

3Gould, E., Perez, D., & Wilson, V. (2023). Latinx workers—particularly women—face devastating job losses in the COVID-19 recession. Economic Policy Institute. https://www.epi.org/publication/latinx-workers-covid/

4Sanchez Cumming, C. (2022). Latino workers are often segregated into bad jobs, but a strong U.S. labor movement can boost job quality and U.S. economic growth. Washington Center for Equitable Growth. https://equitablegrowth.org/latino-workers-are-often-segregated-into-bad-jobs-but-a-strong-u-s-labor-movement-can-boost-job-quality-and-u-s-economic-growth/

5Bahn, K., & McGrew, W. (2018). The intersectional wage gaps faced by Latina women in the United States. Washington Center for Equitable Growth. https://equitablegrowth.org/the-intersectional-wage-gaps-faced-by-latina-women-in-the-united-states/

6Khattar, R., & Vela, J. (2022). Latino Workers Continue To Experience a Shortage of Good Jobs. Center for American Progress. https://www.americanprogress.org/article/latino-workers-continue-to-experience-a-shortage-of-good-jobs/

7Joshi, P., Walters, A. N., Noelke, C., & Acevedo-Garcia, D. (2022). Families’ Job Characteristics and Economic Self-Sufficiency: Differences by Income, Race-Ethnicity, and Nativity. RSF: The Russell Sage Foundation Journal of the Social Sciences. https://doi.org/10.7758/rsf.2022.8.5.04

8Crosby, D., & Mendez, J. (2017). How Common Are Nonstandard Work Schedules Among Low-Income Hispanic Parents of Young Children? National Research Center on Hispanic Children & Families. https://www.hispanicresearchcenter.org/research-resources/how-common-are-nonstandard-work-schedules-among-low-income-hispanic-parents-of-young-children/

9Bartel, A. P., Kim, S., Nam, J., Rossin-Slater, M., Ruhm, C., & Waldfogel, J. (2019). Racial and ethnic disparities in access to and use of paid family and medical leave: evidence from four nationally representative datasets. Monthly Labor Review, 1–29.

10Yavorsky, J. E., Qian, Y., & Sargent, A. C. (2021). The gendered pandemic: The implications of COVID-19 for work and family. Sociology Compass, 15(6). https://doi.org/10.1111/soc4.12881

11Lee, E. K., & Parolin, Z. (2021). The Care Burden during COVID-19: A National Database of Child Care Closures in the United States. Socius, 7. https://doi.org/10.1177/23780231211032028

12Dubina, K. (2021). Hispanics in the Labor Force: 5 Facts. DOL Blog. https://blog.dol.gov/2021/09/15/hispanics-in-the-labor-force-5-facts

13Ferreira van Leer, K., Crosby, D. A., & Mendez, J. (2021). Disruptions to Child Care Arrangements and Work Schedules for Low-Income Hispanic Families are Common and Costly. National Research Center on Hispanic Children & Families. https://www.hispanicresearchcenter.org/research-resources/disruptions-to-child-care-arrangements-and-work-schedules-for-low-income-hispanic-families-are-common-and-costly/

14Luhr, S., Schneider, D., & Harknett, K. (2022). Parenting Without Predictability: Precarious Schedules, Parental Strain, and Work-Life Conflict. RSF: The Russell Sage Foundation Journal of the Social Sciences 8(5), 24–44. https://doi.org/10.7758/RSF.2022.8.5.02

15Chaudry, A., Pedroza, J. M., Sandstorm, H., Danzinger, A., Grosz, M., & Ting, S. (2011). Child Care Choices of Low-Income Working Families. Urban Institute. https://eric.ed.gov/?id=ED578676

16Smith, L., & Owens, V. (2023). Child Care and the Illusion of Parent Choice. Bipartisan Policy Center. https://bipartisanpolicy.org/report/child-care-illusion-of-choice/

17Han, W-J. (2004). Nonstandard work schedules and child care decisions: Evidence from the NICHD Study of Early Child Care. Early Childhood Research Quarterly, 19(2), 231–256. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ecresq.2004.04.003

18Carrillo, D., Harknett, K., Logan, A., Luhr, S., & Schneider, D. (2017). Instability of Work and Care: How Work Schedules Shape Child-Care Arrangements for Parents Working in the Service Sector. Social Service Review, 19(3). https://doi.org/10.1086/693750

19Harknett, K., Schneider, D., & Luhr, S. (2022). Who Cares if Parents have Unpredictable Work Schedules?: Just-in-Time Work Schedules and Child Care Arrangements. Social Problems, 69(1), 164–183. https://doi.org/10.1093/socpro/spaa020

20Chen, Y. (2023). Latino households with children continued to experience pandemic-related disruptions to their child care arrangements. National Research Center on Hispanic Children & Families. https://doi.org/10.59377/629d5724y

21McCrate, E. (2018). Unstable and on-call work schedules in the United States and Canada. International Labour Office. https://www.ilo.org/wcmsp5/groups/public/—ed_protect/—protrav/—travail/documents/publication/wcms_619044.pdf

22Zundl, E., Schneider, D., Harknett, K., & Bellew, E. (2022). Still Unstable: The Persistence of Schedule Uncertainty During the Pandemic. The Shift Project. https://shift.hks.harvard.edu/still-unstable/

23Henly, J. R., & Lambert, S. J. (2014). Unpredictable Work Timing in Retail Jobs: Implications for Employee Work–Life Conflict. ILR Review, 67(3). https://doi.org/10.1177/0019793914537458

24Schneider, D., & Harknett, K. (2021). Hard Times: Routine Schedule Unpredictability and Material Hardship among Service Sector Workers. Social Forces, 99(4), 1682–1709, https://doi.org/10.1093/sf/soaa079

25Ben-Ishai, L., Matthews, H., & Levin-Epstein, J. (2014). Scrambling for stability: The challenges of job schedule volatility and child care. Center for Law and Social Policy. https://www.clasp.org/blog/scrambling-stability-challenges-job-schedule-volatility-and-child-care-0/

26Wilson, J. L. (2002). The impact of shift patterns on healthcare professionals. Journal of Nursing Management, 10(4), 211–219. https://doi.org/10.1046/j.1365-2834.2002.00308.x

27Wildsmith, E., Ramos-Olazagasti, M. A., & Alvira-Hammond, M. (2018). The Job Characteristics of Low-Income Hispanic Parents. National Research Center on Hispanic Children & Families. https://www.hispanicresearchcenter.org/research-resources/the-job-characteristics-of-low-income-hispanic-parents/

28Boal, W. L., Li, J., & Sussell, A. (2018). Health Insurance Coverage by Occupation Among Adults Aged 18–64 Years — 17 States, 2013–2014. Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report (MMWR), 67(21), 593–598 . http://dx.doi.org/10.15585/mmwr.mm6721a1

29Zundl, E., Schneider, D., Goodman, J., Harknett, K., & Bellew, E. (2021). Paid Family and Medical Leave in the U.S. Service Sector. The Shift Project. https://shift.hks.harvard.edu/paid-family-and-medical-leave-in-the-u-s-service-sector/

30Dingel, J. I., & Neiman, B. (2020). How many jobs can be done at home? Journal of Public Economics, 189, 104235. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jpubeco.2020.104235

31U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics. (n.d.). Industries at a Glance: Alphabetical Index. https://www.bls.gov/ebs/factsheets/paid-sick-leave.htm

32U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics. (2023). Industries at a Glance. https://www.bls.gov/iag/tgs/iag_index_alpha.htm

33U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics. (2019). ACCESS TO AND USE OF LEAVE — 2017-2018 DATA FROM THE AMERICAN TIME USE SURVEY. https://www.bls.gov/news.release/archives/leave_08292019.pdf

34U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics. (2023). Flexible work schedule and student loan repayment benefits. https://www.bls.gov/ebs/factsheets/flexible-work-schedule-and-student-loan-repayment.htm

35Rachidi, A. (2016). Child care assistance and nonstandard work schedules. Children and Youth Services Review, 65, 104–111. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.childyouth.2016.03.023

36Ertas, N., & Shields, S. (2012). Child care subsidies and care arrangements of low-income parents. Children and Youth Services Review, 34(1), 179–185. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.childyouth.2011.09.014

37Burstein, N., & Layzer, J. I. (2007). National Study of Child Care for Low-Income Families Patterns of Child Care Use Among Low-Income Families, Final Report: Executive Summary. U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, Administration for Children and Families. https://www.acf.hhs.gov/sites/default/files/documents/opre/patterns_cc_execsum.pdf

38Thomas, H., & Jefferson, A. (2022). The HPOG Training Opportunity: Participant Perspectives on Finding Motivation While Working and Taking Care of Family. Office of Planning, Research, & Evaluation, Administration for Children and Families. https://www.acf.hhs.gov/opre/report/hpog-training-opportunity-participant-perspectives-finding-motivation-while-working-and

39Grant, K., Kersick, J., & Cooper, N. (2021). Lessons From New Hope: Updating the Social Contract for Working Families. Center on Poverty and Inequality, Georgetown Law. https://www.georgetownpoverty.org/issues/lessons-from-new-hope/

40U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics. (2023). Projecting Employment during Pandemic Recovery. https://www.bls.gov/blog/2023/projecting-employment-during-pandemic-recovery.htm

41Flood, S., King, M., Rodgers, R., Ruggles, S., Warren, J. R., & Westberry, M. (2022). Integrated Public Use Microdata Series, Current Population Survey: Version 10.0 [dataset]. IPUMS. https://doi.org/10.18128/D030.V10.0

42Holm, S. (1979). A Simple Sequentially Rejective Multiple Test Procedure. Scandinavian Journal of Statistics, 6(2), 65–70. https://www.jstor.org/stable/4615733

43Rothbaum, J., & Bee, A. (2010). Coronavirus Infects Surveys, Too: Survey Nonresponse Bias and the Coronavirus Pandemic, Working Paper Number SEHSD WP2020-10. United States Census Bureau. https://www.census.gov/library/working-papers/2020/demo/SEHSD-WP2020-10.html

Data and Methodology

This brief draws from two primary data sources: the Current Population Survey (CPS) Annual Social and Economic Supplement (ASEC) and the Business Response Survey (BRS) (see below).

Current Population Survey (CPS) Annual Social and Economic Supplement (ASEC)

Data. The CPS is a nationally representative survey of U.S. households used to produce relevant labor statistics and published by the Bureau of Labor Statistics (BLS). The ASEC supplement is conducted in March and, while it surveys a smaller sample of respondents, it gathers data on socioeconomic indicators that allow us to identify Latino parents with low incomes. We obtained these data from IPUMS for years 2018 through 2022 to cover the pre- and post-pandemic contexts.41

Sample. Using the CPS ASEC, we define households with low incomes as those with incomes below 200 percent of the poverty threshold. For our analyses, we identified Latino parents by the presence of respondents’ own children under age 18 in the household, based on self-reports of race and ethnicity. We also identified Latino parents as being born in or outside the United States, also based on self-report. We limited our analysis to Latino parents of children under age 18 with low incomes who were employed in March 2018-2019 and March 2021-2022. Employed parents are those who have a job and were working in the prior week and those who have a job but were not at work in the prior week.

Measures. We identified the industry and occupation of Latino parents’ main job, which is the job where they worked the most hours in the reference week. Because industry and occupation codes changed from 2018-2019 to 2021-2022, we used the crosswalks provided by the Census Bureau to group specific industries and occupations into broad categories that are comparable across these years. The analyses used cross-sectional data from 2018-2022. Thus, it is possible that some of the observed changes may be due to employed persons switching industries and/or occupations or leaving the labor market, as well as compositional changes in the ASEC samples.

Analyses. Our descriptive analyses calculated the industry and occupational distribution of Latino parents with low incomes in March of the survey year, averaging across 2018-2019 for the pre-pandemic period and across 2021-2022 for the post-pandemic period. We used two-year averages to address concerns with small sample sizes given our sample restrictions and the fact that the ASEC includes a smaller sample of CPS respondents. We only show percentages for all industries in which at least roughly 5 percent of Latino parents with low incomes worked, but use all industries to calculate the distributions. We also only show percentages for the top 10 occupations of Latino parents but calculate these percentages for all occupations. We then tested whether any observed differences in the industries and occupations of Latino fathers and mothers with low incomes between these two time periods were statistically significant. Given the large number of statistical tests, we used Holm (1979) Family Wise Error Rate (FWER) correction for p-values and indicate in the figures any differences that remained statistically significant after this correction.42 Because of the gendered nature of work opportunities, we conducted analyses separately for fathers and mothers. All analyses were weighted using the individual ASEC sampling weights.

Note that data collection in the CPS was affected by the pandemic. Estimated response rates in the ASEC, which draws from different rotation groups, suggest they were lower at the start of the pandemic, dropping from 67.6 in 2019 to 61.1 in 2020.43 While usual non-response can be adjusted with survey weights, non-response patterns in 2020 were unique in ways that could affect conclusions drawn from the data. Estimates show that, during 2020, ASEC respondents had higher incomes than in prior years, even when adjusting using the regular weights.

To understand how our pre- (2018-2019) and post-pandemic (2021-2022) samples differ in ways that could affect our findings, we compared the two samples across gender, age, low-income status, employment, country of birth (U.S. or another country), number of children, and number of children under age 5. We weighted our analyses using the ASEC individual weights because the COVID-19 weights developed by Rothbaum and Bee (2021) were not available for 2018 and 2022. We find that, on average, the pre- and post-pandemic samples are similar.

To test the sensitivity of our main estimates to compositional changes and the choice of ASEC years in our analytical sample, we re-estimated our results using the COVID-19 corrected weights designed by Rothbaum and Bee (2021). These weights are only available for 2019-2021, so this analysis is limited to comparing these two years only. Overall, we find that the conclusions outlined in this brief—that Latino parents are largely working in similar occupations pre- and post-pandemic, with few changes in the occupations of Latina mothers and fathers—remain regardless of the sample choice or the weighting. These additional analyses are available from the authors.

Business Response Survey (BRS)

The BRS is a survey of private U.S. business establishments that the BLS started in 2020 to understand how the labor market had changed due to the COVID-19 pandemic and, more generally, how the labor market responds to various events. In this brief, we used the 2020 and 2021 data by industry, which asks about changes occurring since the onset of the pandemic through September 2020 and 2021, respectively.

We used industry-level responses that we restricted to the industries employing Latino parents with low incomes, identified in the CPS analyses. We downloaded all relevant tables from the BRS website, which are available in Excel format, and produced descriptive figures showing the percentage of business establishments within the industries employing Latino parents with low incomes that started or increased each of the practices identified in the literature as relevant for child care: leave, flexible schedules, and telework.

Note that industries are not included consistently across all BRS years. In particular, some BRS tables combine health care and social assistance while others show them separately. Similarly, administrative and support and waste management is not shown in all BRS tables. This is why the industry lists in Figures 3-6 are not always consistent. The BRS does not provide pre-pandemic baseline data and the publicly available data—with the exception of telework—only report the percentage of businesses in the private sector that started or increased a benefit or flexibility. The public data do not report the percentage that did not offer that benefit or that did not make any changes to their benefits and flexibilities as a result of the pandemic. When available, we obtained pre-pandemic data from BLS’ National Compensation Survey – Benefits.