Jul 25, 2025

Research Publication

Subsidy Eligibility Policies to Support Working Families Vary Across Hispanic-Populous States

Authors:

As with many parents in the low-wage workforce, Hispanic parents often work nontraditional and variable hours, hold multiple jobs, and engage in a range of job search and training activities to support their families financially.1 These employment characteristics may be associated with schedule and earnings fluctuations that make it challenging for parents to secure the child care they need to sustain their employment and obtain economic stability. Additionally, child care arrangements that can be flexibly used and reliably cover parents’ work hours are often in short supply and may be unaffordable.

Child care subsidies can help address these challenges, but states and territories vary widely in their policies outlining which families qualify for assistance. Child care subsidy programs with higher income thresholds, those that support a wide range of qualifying activities, and those with more flexible policies around work and care hours have the potential to serve a broader range of working families—in particular those with low-wage jobs.

According to federal law,2 children younger than age 13 are eligible for subsidies from the Child Care and Development Fund (CCDF) as long as they live with a parent who is working, training, or going to school; and their family income does not exceed 85 percent of the state median income (SMI), with family assets of less than $1 million. Within these federal parameters, lead agencies in states and territoriesa (hereafter referred to as “states” for simplicity) have considerable flexibility to develop their own eligibility policies and procedures. For example, lead agencies help determine which families can receive subsidies by setting income eligibility thresholds, defining qualifying activities and work hour requirements, and expediting eligibility determinations for state-identified priority populations (e.g., parents participating in Temporary Assistance for Needy Families or families experiencing homelessness).

In this brief, we highlight state-level variation in policies and procedures that shape who is eligible for child care subsidies and considers how these variations may impact Hispanic families, who represent a large segment of the low-income workforce and those eligible for federal assistance programs. We focus on seven policy strategies, described below, that may be more responsive to the realities of working parents’ needs by offering flexibility and broadening who can qualify for assistance. These strategies reflect flexibilities offered to lead agencies, either through federal statute (2014 CCDBG Reauthorization Act) or federal program guidelines (2024 Final Rule). Drawing on lead agencies’ descriptions of their CCDF programs for fiscal years (FYs) 2025-2027, we summarize the extent to which these policy strategies are being used in Puerto Rico and 15 states that are home to more than 80 percent of Hispanic children in U.S. households with low incomes (hereafter “Hispanic-populous states”).3

Seven CCDF Policy Strategies That States May Implement to Support Subsidy Eligibility for Working Families

- Income eligibility threshold at or above 85 percent of state median income (SMI). The CCDBG Act of 1996 set the maximum income eligibility level at 85 percent of the SMI (42 U.S.C. § 9857 et seq.), although states have the option to set a lower threshold. Lead agencies may also use non-CCDF funds to extend eligibility to families with incomes above the federal cap of 85 percent SMI. In this analysis, we report on the number of Hispanic-populous states (including Puerto Rico) that provide subsidy eligibility to families at or above the maximum federal threshold.

- Accounting for fluctuations in earnings for eligibility determination. According to federal regulations, lead agencies must account for fluctuations in earnings or wages when determining eligibility and ensure that temporary increases do not impact eligibility or family copayments (CCDBG Act of 2014). In their CCDF plans, states indicate whether they address this by using one or more of the following strategies: (1) average family earnings over a specified period of time (e.g., 12 months), (2) use earnings statements most representative of families’ monthly incomes, or (3) deduct temporary increases in earnings or wages from family income.

- Qualifying activities include job search. According to federal regulations, lead agencies can choose to consider employment seeking or job search as a qualifying activity for receiving subsidies. Lead agencies that opt to do this must allow for a minimum of three months of job search (45 CFR 98.21).

- Qualifying activities include English as a Second Language classes. States have discretion to define the parent employment, job training, or education activities they approve for care. These are not specified in federal guidelines but asked about in CCDF Plans. In this analysis, we report on the number of lead agencies that include English as a Second Language classes in their definition of attending “job training” or “educational program” to qualify families for child care assistance.

- Time for travel and/or meals and breaks included in subsidy coverage. There is no federal requirement that authorized child care services must be limited to the specific hours that parents are working or engaged in training or education. In this analysis, we report on the number of lead agencies that choose to include time associated with these activities (i.e., travel, meals, and breaks) within their definitions of qualifying activities and time approved for care.

- No minimum work hours required. Federal regulations do not require a minimum number of work, training, or educational activity hours for families to qualify for child care assistance, although lead agencies may opt to impose such a requirement. In this analysis, we report on the number of lead agencies that do not condition eligibility on a minimum number of parent activity hours.

- Tool available for families to self-assess their eligibility for subsidies. One practice encouraged in federal guidelines to reduce enrollment barriers is to make a screening tool available to families so they can self-assess their eligibility (45 CFR 98.21). Lead agencies that choose to use this practice often post this tool on their consumer education website. In this analysis, we report the number of lead agencies that say they have such a tool available.

About the Policies and Practices Shaping Child Care Subsidy Access in Hispanic-Populous States Series

The Child Care and Development Block Grant Act of 1990 (CCDBG), as amended in 2014, is the main federal law governing child care programs that support parents’ employment, families’ economic security, and children’s learning and development. Through the Child Care and Development Fund (CCDF) program, state, territory, and Tribal lead agencies receive federal CCDBG dollars to help subsidize eligible families’ child care expenses and improve the quality and supply of affordable care options in communities.

Federal CCDF regulations, as set forth in the CCDBG statute or the 2024 Final Rule, include both program requirements and flexibilities that lead agencies may opt to use to meet their specific program goals. The final rule also includes federal recommendations to inform state program design and operations. Within broad federal guidelines, lead agencies have considerable discretion to structure their CCDF programs in ways that align with state priorities and family and community needs. To apply for continued federal funding, lead agencies must submit a triennial CCDF Plan to the federal Office of Child Care that describes how their program is meeting regulatory provisions and how it will direct CCDF funds for the next three years.

In this series, we draw on lead agency CCDF Plans for fiscal years (FYs) 2025-2027 to describe the extent to which various strategies—both required and optional—are in effect in Puerto Rico and across 15 states with large populations of Hispanic children eligible for child care subsidies (“Hispanic-populous states”): Arizona, California, Colorado, Florida, Georgia, Illinois, Massachusetts, Nevada, New Jersey, New Mexico, New York, North Carolina, Pennsylvania, Texas, and Washington. Across the series, we focus on subsets of policies and practices with potential relevance for Hispanic families’ child care access, several of which reflect requirements or flexibilities newly established in the 2024 Final Rule. In addition to the current summary of state policy strategies related to subsidy eligibility, we have conducted similar policy scans related to family copayments and care affordability. A third piece focused on the application process is forthcoming.

Findings

In Puerto Rico and the 15 Hispanic-populous states included in our scan, fewer than half (6 of 16) set their initial income eligibility for child care subsidies at or above 85 percent of the SMI. Among these, five lead agencies (California, Nevada, New York, Texas, and Puerto Rico) set their initial income eligibility threshold at the maximum federal level (85% SMI), while New Mexico uses state-only funds to support a higher threshold and offer subsidies to families in a wider income range. The maximum initial income eligibility threshold for a family of four ranges from 40 percent SMI in New Jersey to 152 percent SMI in New Mexico (see Appendix Table 1).

Figure 1. Less than half of Hispanic-populous states set their initial income eligibility for child care subsidies at or above 85 percent of the SMI.

States categorized by maximum initial income eligibility threshold

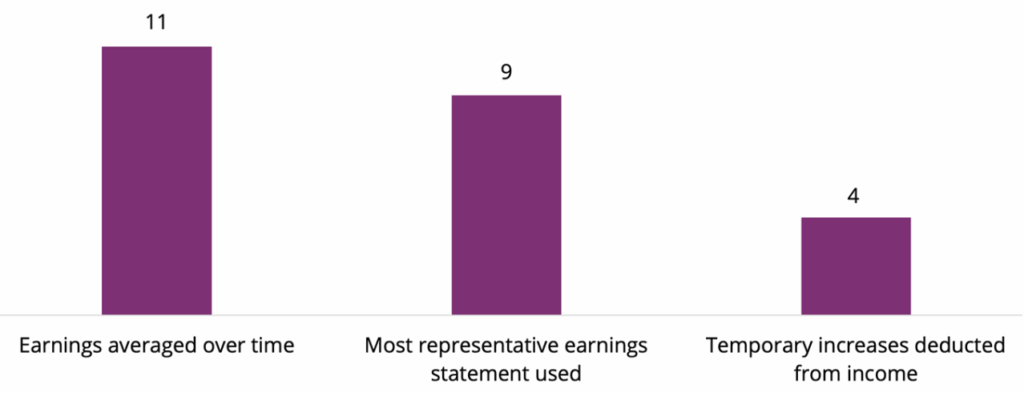

To account for earnings fluctuations when determining subsidy eligibility, most Hispanic-populous states (11 of 16) average families’ earnings over time, roughly half (9 of 16) use earnings statements that are most representative of families’ income, and a few (4 of 16) also deduct temporary increases in income. Most lead agencies included in this policy scan (10 of 16) report implementing only one of the strategies asked about in the CCDF plan document, while four states report using two strategies and two states report using all three (see Appendix Table 1). The use of multiple strategies may offer needed flexibility to accommodate individual family circumstances; however, it is unclear from the CCDF plans how and when states use this flexibility. Notably, the most common practice across the states—averaging earnings over time—often requires parents to submit several months or more of earnings documentation.

Figure 2. Hispanic-populous states use several strategies to account for earnings fluctuations in determining family eligibility for subsidies.

Number of states implementing three strategies to account for earnings fluctuations

Notes. Because states/territories may use more than one strategy to account for earnings fluctuations, the columns total to more than the 16 states/territories included in this scan.

Among Hispanic-populous states, just over half (9 of 16) include job search as a qualifying activity for initial subsidy eligibility. In four of these states, this allowance applies to specific populations only. For example, in California, North Carolina, and Washington, employment seeking is an eligible activity only for parents enrolled in state employment and training programs; in Pennsylvania, it applies only to families experiencing homelessness. In the remaining five states that consider job search an eligible activity, it is described as applying more broadly.

Figure 3. Just over half of Hispanic-populous states consider job search to be a qualifying activity.

States categorized by whether they consider job search a qualifying activity

Among Hispanic-populous states, most lead agencies (12 of 16) include English as a Second Language classes in their definition of allowable job training or educational activities.

Figure 4. Most Hispanic-populous states include English as a Second Language (ESL) among their allowable training or educational activities.

States categorized by whether they consider ESL classes a qualifying activity

Most Hispanic-populous states (12 of 16) include commuting and/or meals and breaks in the time approved for child care subsidy coverage. Many of the lead agencies included in this policy scan opt to cover job-related time beyond parents “on the clock” work (i.e., travel, meals, and break times) in the number of hours they approve for subsidized care. This strategy may help support parents’ employment efforts by recognizing that the workday can require time beyond the hours covered by wages.

Figure 5. Most Hispanic-populous states include commutes and/or meals and breaks in time approved for subsidy coverage.

States categorized by subsidy coverage beyond paid work hours

Among Hispanic-populous states, fewer than half (7 of 16) have no minimum weekly number of activity hours required to qualify for child care subsidies. Lead agencies with no minimum weekly work hour requirements may make subsidies available to a broader set of working parents given the volatile and unpredictable nature of work hours and schedules for many in the low-wage workforce.4 More than half of the lead agencies included in this scan (9 of 16) impose a minimum work hour requirement, which restricts subsidy eligibility to children whose parents are engaged in qualifying activities for a set number of hours per week.

Figure 6. Fewer than half of the 16 Hispanic-populous states have no minimum work hour requirement.

States categorized by minimum work hour requirement

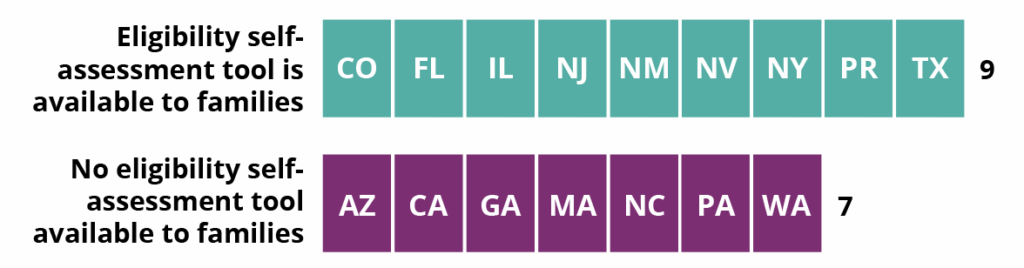

Among Hispanic-populous states, just over half (9 of 16) include a tool on their consumer education website to help families self-assess their eligibility. This resource may help families understand their options, reduce informational barriers, and help them navigate the subsidy application process. Seven of the lead agencies included in this scan do not have this type of pre-screening tool publicly available.

Figure 7. Nearly half of the 16 Hispanic-populous states make an eligibility screening tool available to families.

States categorized by availability of eligibility self-assessment tool

Source: Authors’ review of state and territory Child Care and Development Fund Plans FY 2025-2027 (and appendices) approved and posted by the Office of Child Care, as of March 2025, https://acf.gov/occ/form/approved-ccdf-plans-fy-2025-2027.

Source: Authors’ review of state and territory Child Care and Development Fund Plans FY 2025-2027 (and appendices) approved and posted by the Office of Child Care, as of March 2025, https://acf.gov/occ/form/approved-ccdf-plans-fy-2025-2027.Summary and Implications

The eligibility-related policies and practices that state CCDF lead agencies choose to implement directly influence the number of families who can qualify for child care subsidies and the amount of subsidized care parents can access to support their employment and self-sufficiency efforts. While existing CCDF funds are insufficient to cover all who are eligible for child care subsidies, the policy strategies reviewed in this scan can widen the range of low-income working families who qualify for potential assistance and provide necessary flexibility, given that low-wage employment tends to be more unpredictable and volatile than higher-wage work.

We find that most Hispanic-populous states and territories have income eligibility limits that are more restrictive than allowable by federal rules. This strategy may ensure that limited CCDF funds are directed to families with the lowest incomes, but it may also mean that many parents in the low-wage workforce are excluded from critical child care assistance. Only 5 of the 16 lead agencies included in this scan set their initial income eligibility at the federal maximum threshold of 85 percent of state median income, and only one state (New Mexico) uses state funds to offer eligibility to families with incomes up to approximately 150 percent SMI.

We also find that just over half of the 16 lead agencies consider job search an eligible activity, and that three quarters define qualifying activities broadly to include time beyond paid work hours, such as English language classes and time for commuting, meals, and breaks; seven of the lead agencies do not have a minimum work hour requirement. In addition, consistent with federal CCDF regulations, all 16 states use one or more methods to account for irregular income fluctuations, with the most common approach being to average earnings over a specified period of time. Finally, many—but not all—lead agencies included in this scan opt to provide families with a screening tool to help them self-assess their eligibility for subsidies. This consumer education tool may help families be better informed and prepared for the application process and may expedite eligibility determinations.

Together, the strategies included in this scan recognize the realities of many parents’ employment experiences and their need for flexible, yet simple, eligibility criteria. Notably, none of the Hispanic-populous states and territories we reviewed implement all seven of the eligibility-related strategies; however, one state (California) implements six of them. Additional research on the implications of specific policy choices by lead agencies related to subsidy eligibility and how these are applied in practice would be useful. For example, the strategy of averaging earnings over time to “smooth out” fluctuations may help ensure that temporary increases do not disqualify otherwise eligible families. At the same time, however, this strategy may also increase burdens—both for families and staff—if it requires collecting multiple months of paystubs. The practical reach of more expansive or flexible eligibility policies will also depend on federal and state funding levels and the numbers of qualifying children and families who can be served.

Methods

The data reported in this brief come from a review of publicly available state and territory CCDF plans for federal fiscal years 2025-2027, submitted to and approved by the federal Office of Child Care with the Administration of Children and Families, U.S. Department of Health and Human Services. Every three years, to apply for federal funds, state, territory, and Tribal grantees submit a CCDF Plan that describes—and provides assurances for—how the lead agency will administer its child care program in alignment with federal regulations. We focused our analysis on Puerto Rico and 15 states with large populations (i.e., greater than 100,000) of Hispanic children who live in households with low incomes (i.e., below 200% of the federal poverty level, as a key population to be served by the federal child care subsidy program.5

The particular CCDF eligibility policies and practices summarized in this analysis were selected because of their potential relevance for Hispanic families’ access to and utilization of child care subsidies. Hispanic parents have relatively high levels of employment and many experience job characteristics associated with variable hours and earnings. Less restrictive, more flexible eligibility policies may allow more working parents to access subsidies. As noted above, the policy strategies reviewed here represent flexibilities for which lead agencies may choose whether and how they apply to their programs. In this analysis, we identify lead agencies as using a particular policy strategy only if they reported it as an element of their program effective FY 2025-2027 (October 1, 2024 – September 20, 2027). The data presented in this brief do not capture any policy or legislative changes that occurred after approved state/territory CCDF Plans were posted on the ACF website in January 2025. More detailed and up-to-date information about the implementation of state/territory CCDF programs can typically be found in lead agency caseworker manuals and are tracked on an annual basis in the CCDF Policies Database.

Footnote

a Tribal lead agencies also administer CCDF programs and are subject to some of the same federal regulations, while also having unique considerations. Given our focus on states and territories with large populations of subsidy-eligible Hispanic children, we do not include Tribal CCDF programs in this policy scan.

Suggested Citation

Crosby, D.A., Wrather, A., Jacome Ceron, A., Mendez, J., & Omondi, F. (2025). Subsidy eligibility policies to support working families vary across Hispanic-populous states. National Research Center on Hispanic Children & Families. DOI: 10.59377/915r5655z

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to thank the Steering Committee of the National Research Center on Hispanic Children & Families—along with Kristen Harper and Laura Ramirez—for their helpful comments, edits, and research assistance at multiple stages of this project. The Center’s Steering Committee is made up of the Center investigators—Drs. Natasha Cabrera (University of Maryland, Co-PI), Danielle Crosby (University of North Carolina at Greensboro, Co-PI), Lisa Gennetian (Duke University; Co-PI), Lina Guzman (Child Trends, PI), Doré LaForett (Child Trends, Co-I), Julie Mendez (University of North Carolina at Greensboro, Co-PI), and Maria Ramos-Olazagasti (Child Trends, Deputy Director and Co-PI)—and federal project officers Drs. Jenessa Malin and Kimberly Clum (Office of Planning, Research and Evaluation).

This product is supported by Grant Number 90PH0032 from the Office of Planning, Research & Evaluation within the Administration for Children and Families, a division of the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services totaling $7.84 million with 99 percentage funded by ACF/HHS and 1 percentage funded by non-government sources. Neither the Administration for Children and Families nor any of its components operate, control, are responsible for, or necessarily endorse this product. The opinions, findings, conclusions, and recommendations expressed are those of the author(s) and do not necessarily reflect the views of the Administration for Children and Families and the Office of Planning, Research & Evaluation. For more information, please visit the ACF website, Administrative and National Policy Requirement.

Editor: Brent Franklin

Designers: Catherine Nichols and Joseph Boven

About the Authors

Danielle A. Crosby, PhD, is a co-principal investigator of the National Research Center on Hispanic Children & Families, co-leading the research area on early care and education. She is an associate professor in the Department of Human Development and Family Studies at the University of North Carolina at Greensboro. Her research focuses on understanding how policies and systems shape early education access and quality for young children in low-income families.

Amy Wrather, MS, is a doctoral student in the Human Development and Family Studies department at the University of North Carolina at Greensboro. She recently completed her Master’s degree in the same program. Her research interests focus on promoting high-quality learning environments for young children with disabilities across traditional and alternative models of early childhood education.

Anyela Jacome Ceron, MPS, is a graduate student in a Clinical Psychology program at the University of North Carolina at Greensboro. She received her Master’s degree from the University of Maryland, College Park in Clinical Psychological Science. Her research interests focus on the well-being of children and families and understanding risk and protective factors in the context of culture. She also has interests in family engagement in early care and education programs.

Julia Mendez, PhD, is a co-principal investigator of the National Research Center on Hispanic Children & Families, co-leading the research area on early care and education. She is a professor in the Department of Psychology at the University of North Carolina at Greensboro. Her research focuses on risk and resilience among low-income and Latino children and families, with an emphasis on parent-child interactions and family engagement in early care and education programs.

Favour Omondi, MS, is a doctoral student in the Human Development and Family Studies department at the University of North Carolina at Greensboro. She recently completed her Master’s degree in the same program. Her research interests focus on the multi-level factors that place young children at risk for maltreatment and the role of protective mechanisms (including access to high-quality early childhood education) in mitigating these risks.

About the Center

The National Research Center on Hispanic Children & Families (Center) conducts research to inform programs and policy to better serve Hispanic children and families with low incomes. Our research focuses on poverty reduction and economic self-sufficiency; child care and early education, including federal programs such as Head Start (HS) and the Child Care and Development Fund (CCDF); and cross-cutting topics that include parenting, family structure, and family dynamics. The Center is led by Child Trends, in partnership with Duke University, University of North Carolina at Greensboro, and University of Maryland, College Park.

Copyright 2025 by the National Research Center on Hispanic Children & Families.

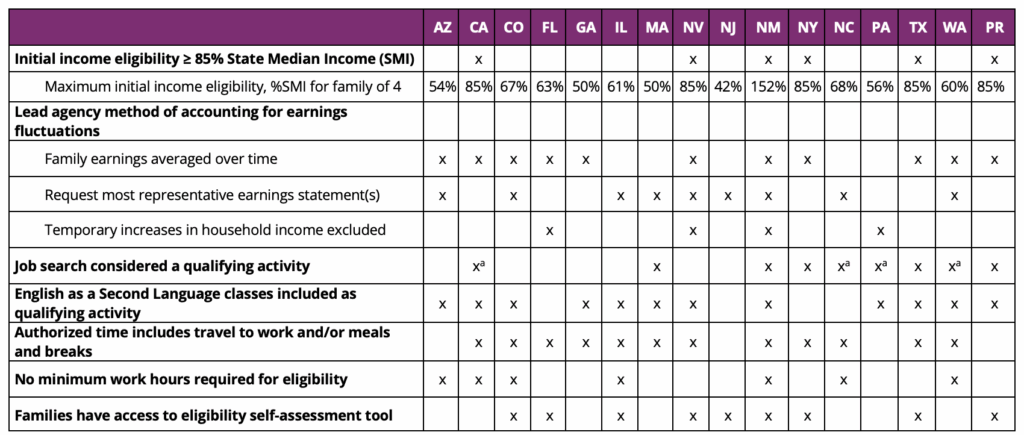

Appendix

Appendix Table 1. Variation in Key CCDF Policies Related to Eligibility Across 16 States/Territories With Large Populations of Hispanic Children

Source: Authors’ review of state and territory Child Care and Development Fund Plans FY 2025-2027 (and appendices) approved and posted by the Office of Child Care, as of March 2025, https://acf.gov/occ/form/approved-ccdf-plans-fy-2025-2027.

Source: Authors’ review of state and territory Child Care and Development Fund Plans FY 2025-2027 (and appendices) approved and posted by the Office of Child Care, as of March 2025, https://acf.gov/occ/form/approved-ccdf-plans-fy-2025-2027.Notes. a In these states/territories, job search or employment seeking is considered an eligible activity only for certain populations (e.g., participants in state job programs, families experiencing homelessness), as specified in section 2.5.3.a.i. of the FY 2025-2027 Plans.

References

1 Wildsmith, E., Ramos-Olazagasti, M.A., & Alvira-Hammond, M. (2018). The Job Characteristics of Low-Income Hispanic Parents. National Research Center on Hispanic Children & Families. https://www.hispanicresearchcenter.org/research-resources/the-job-characteristics-of-low-income-hispanic-parents/

2 CCDBG Reauthorization Act of 2014. https://www.govinfo.gov/content/pkg/PLAW-113publ186/pdf/PLAW-113publ186.pdf

3 Ramirez, L., Guzman, L., & Alvira-Hammond, M. (2024). Latino children represent at least 1 in 4 kids nationwide, and more than 40 percent in 5 states and Puerto Rico. National Research Center on Hispanic Children & Families. https://doi.org/10.59377/865v5358m

4 Crosby, D.A., & Mendez, J.L. (2017). How Common Are Nonstandard Schedules Among Low-Income Hispanic Parents of Young Children? National Research Center on Hispanic Children and Families. https://www.hispanicresearchcenter.org/research-resources/how-common-are-nonstandard-work-schedules-among-low-income-hispanic-parents-of-young-children/

5 Alvira-Hammond, M. (2024). 2022 American Community Survey (ACS)/Puerto Rican Community Survey (PRCS) 1-Year Estimates. [Unpublished analyses]. IPUMS USA, University of Minnesota. www.ipums.org