Jul 31, 2018

Research Publication

Who is Caring for Latino Children? The Characteristics of the Early Care and Education Teachers and Caregivers Serving a High Proportion of Hispanic Children

Authors:

Overview

The child population in the United States is becoming increasingly diverse,1 led, in part, by the growth in the Hispanica child population.2 As a result, any disadvantages that Hispanic children face are increasingly important on a national scale. Latino children, on average, score lower on common measures of school readiness—including cognitive, literacy, and numeracy skills—relative to their black and white peers.3,4 These gaps are more pronounced when neither parent in the household speaks English.4

An expanding body of research indicates that high-quality early care and education (ECE) programs support children’s development, and can help close racial/ethnic gaps in school readiness, especially for low-income and non-English-speaking children.5-8 The effects of ECE are largely dependent on the teachers and caregivers in these programs,9 yet we know little about who teaches and cares for Hispanic children before they enter primary school.

This brief examines three aspects of the ECE workforce that are linked with how children learn,10 their socioemotional development,11-13 and classroom environment and quality of care.14-16

- Training, experience, and education17,18

- Attitudes, including motivations for working with children16

- Linguistic and racial and ethnic diversity11,19,20

Drawing from the National Survey of Early Care and Education (NSECE), the first nationally representative survey to provide a national portrait of the ECE workforce, we examine these characteristics across three teacher or caregiver typesb: center-based staff (which includes lead and assistant teachers, as well as aides working in Head Start, Pre-K, and other community-based centers); listed, home-based teachers and caregivers (which generally includes those who care for at least one child with whom they have no prior relationship); and unlisted, home-based teachers and caregivers (which generally includes relatives, friends, and neighbors who provide care to children with whom they had a prior relationship). We compared these features of the workforce among teachers and caregivers of children ages 0 to 5cworking in high-Hispanic-servingd settings (defined as settings where 25 percent or more of the children served are Hispanic) with those in low-Hispanic-serving settings (i.e., those teachers and caregivers in settings where less than 25 percent of the children enrolled are Hispanic).

Key Findings

Our national portrait of teachers and caregivers in high-Hispanic-serving settings finds that:

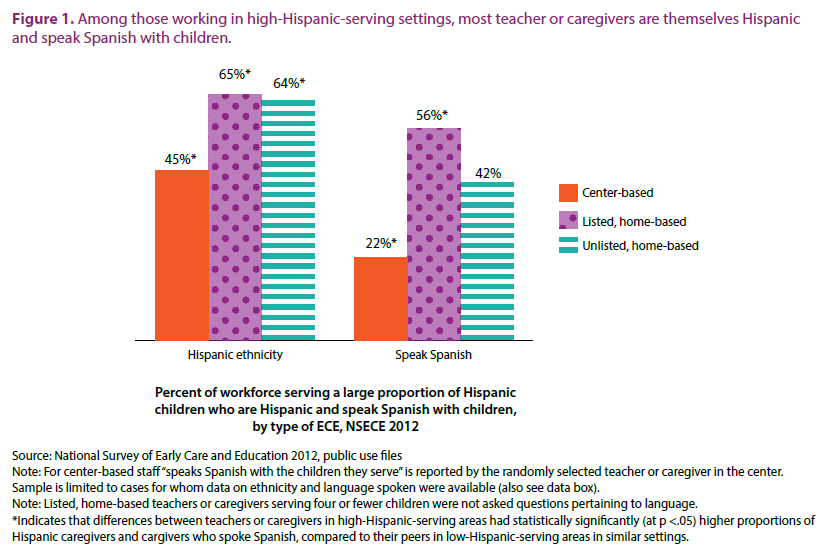

- Teachers and caregivers in high-Hispanic-serving settings are more ethnically diverse and more likely to speak Spanish with the children they serve relative to their peers in low-Hispanic-serving settings.

- Just under half of the teachers and caregivers working in centers—and two-thirds of listed and unlisted home-based teachers and caregivers—are Hispanic.

- Many teachers and caregivers in high-Hispanic-serving centers and listed, home-based settings serving four or more childrene speak Spanish at least half of the time with the children they serve, and are more likely to do so than their low-Hispanic-serving counterparts.

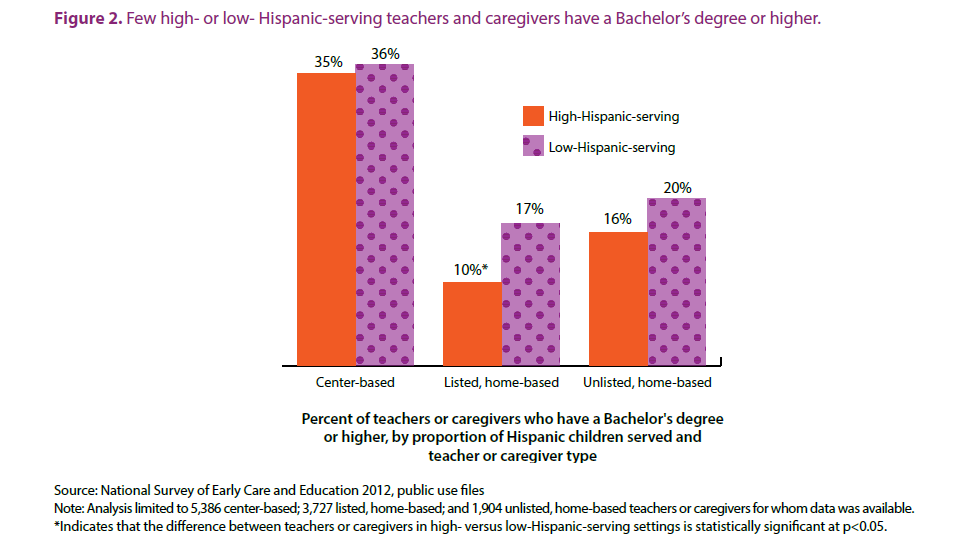

- Few high- or low-Hispanic-serving teachers and caregivers have a Bachelor’s degree or higher.

- In general, teachers and caregivers who serve a high proportion of Hispanic children have similar levels of education to their peers who serve a low proportion.

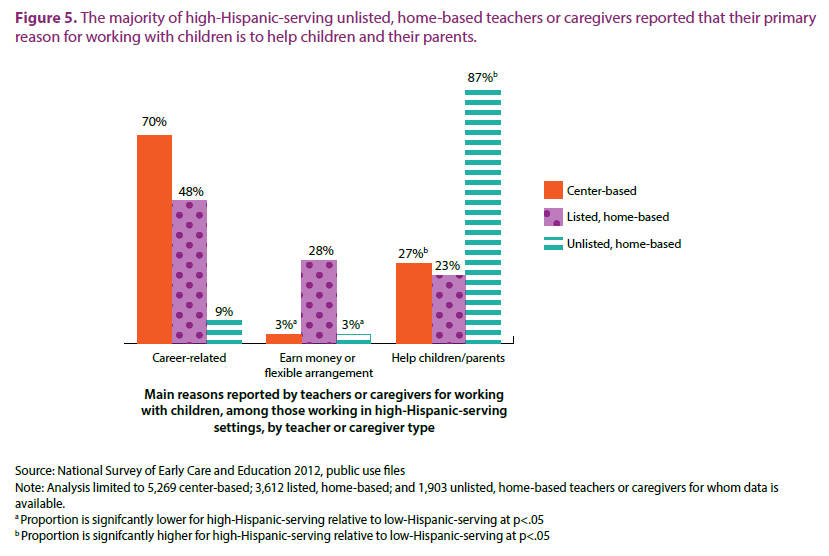

- Among those who attended college, staff in high-Hispanic-serving centers are more likely to have majored in ECE or a related field, relative to their low-Hispanic-serving peers.

- Teachers and caregivers who work in settings that serve either high or low proportions of Hispanic children have similar years of experience caring for young children.

- Roughly half of center-based and unlisted, home-based teachers and caregivers in high-Hispanic-serving settings have more than 10 years of experience—similar to their peers in low-Hispanic-serving centers.

- Most teachers and caregivers in high-Hispanic-serving settings think of their work as a career or as a way to help kids and parents; few report thinking of their work as a means to a paycheck.

- Differences in teacher and caregiver characteristics between high- and low-Hispanic-serving settings may be a function of their funding sources.

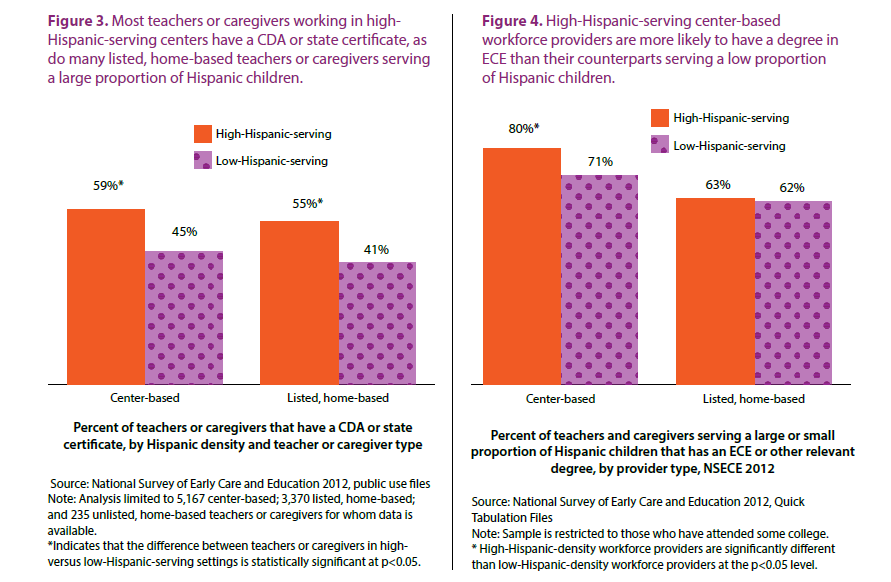

- For example, more than half of teachers and caregivers in high-Hispanic-serving centers and listed, home-based settings have a Child Development Associate or state certification. This could reflect the fact that many high-Hispanic-serving centers receive public funding (e.g. Headstart, Public Pre-K, etc.).

Data and Methods

Data for this brief come from the 2012 National Survey of Early Care and Education (NSECE). The NSECE is a set of four interrelated, nationally representative surveys that describe the ECE landscape in the United States. This brief uses the public use files for the center survey, the center-based workforce survey, and home-based provider survey. The center-based survey was conducted with directors of ECE programs identified from state-level lists, such as licensing lists.

The center-based workforce survey sample consists of one teacher or other instructional staff member that was randomly selected from an organization to complete an interview. The center-based workforce sample includes lead teachers, assistants, and aides working in Head Start and pre-kindergarten programs, as well as community-based centers. The listed, home-based sample is a nationally representative sample of child care teachers or caregivers who provide home-based care and appear in publicly available lists. This includes home-based teachers or caregivers who care for at least one child with whom they have no prior relationship, but may also include relatives, friends, and neighbors who provide care and are registered on publicly available lists to meet state regulations (for example, to receive child care subsidies). Unlisted, home-based teachers or caregivers are individuals identified through the NSECE household roster as providing care for children under age 13—when those children are not their own—at least five hours a week, a category that generally includes relatives, friends, and neighbors who provide care for children with whom they have a prior relationship. According to the NSECE, there were approximately 3.8 million home-based teachers or caregivers in 2012 serving children from birth to age 5, and not yet in kindergarten. Most of these teachers or caregivers were unlisted, with 3.6 million unlisted and 117,900 listed, home-based teachers or caregivers. About 1 million home-based teachers or caregivers were paid for providing care, including 115,000 listed and 919,000 unlisted teachers or caregivers.23 For the most part, questions asked of listed and unlisted home-based teachers or caregivers were comparable to those asked of center-based staff. In some cases, however, NSECE interviewers skipped questions for the home-based sample if the question was deemed inappropriate for the respondent’s situation (see additional detail below). This was often the case with teachers or caregivers who cared only for children with whom they had a prior relationship (i.e., friend, relative, or neighbor). Additionally, only home-based teachers or caregivers serving four or more children were asked about what language they usually speak with the children they serve.

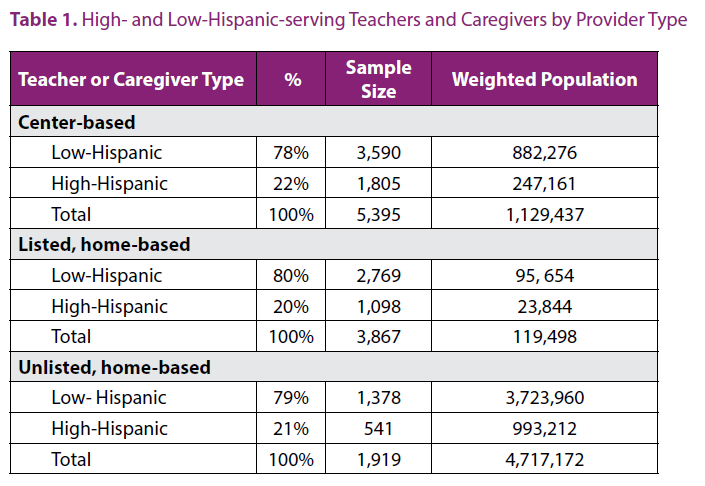

The analytic sample for this brief includes 5,395 center-based; 3,867 listed, home-based; and 1,919 unlisted, home-based teachers or caregivers serving children ages 0 to 5, and for whom data on Hispanic density was available. Since this brief focuses on the characteristics of the ECE workforce, the unit of analysis is the individual teacher or caregiver; we examine the characteristics associated with that individual to the extent possible.

Table 1 shows sample sizes for high- and low-Hispanic-serving teachers and caregivers by teacher or provider type.

Definitions of the variables used to describe the characteristics of those working in high-Hispanic-serving settings are provided below. To examine the characteristics of center-based staff, we combined the center and center-based workforce surveys. This allowed us to obtain data on the proportion of Hispanic children served, as well as institutional characteristics that were only collected in the center survey. One important caveat is that the data collected from center-based teachers or caregivers reflect their individual characteristics and experiences in the classroom, while the data on Hispanic density reflect the overall racial/ethnic composition of the center. There may not be a one-to-one correspondence between center teacher or caregiver characteristics and Hispanic density. That is, the group of children with whom a teacher or caregiver typically works may be different from the overall composition of the center. This limitation of the data applies to centers only. Those variables for which there is not a one-to-one correspondence are noted below with an asterisk.

High-Hispanic-serving* indicates that 25 percent or more of the children served by the teacher or caregiver are Hispanic.

Spanish language spoken with children was constructed from a combination of measures to determine whether the teacher or caregiver spoke Spanish with the children they serve. We coded listed and unlisted home-based teachers or caregivers as speaking Spanish if they responded affirmatively to a question about whether they “usually speak Spanish with children.” Information about listed, home-based teachers’ or caregivers’ language should be interpreted cautiously, because only those serving more than four children were asked questions about their language.

We report two measures for center-based teachers and caregivers: “Do you speak any languages other than English?” and “About what percent of the time that you are working with children do you speak English?” Information about center staff languages (other than English) is suppressed in the public use files to protect the identity of the respondents. We know that most workforce teachers or caregivers speak English and/or Spanish,25 so we assume that nearly all respondents who report speaking another language speak Spanish, and that when teachers or caregivers are not speaking English they are speaking Spanish. Realistically, diversity of other languages is captured in these measures but we cannot disaggregate it.

Race/ethnicity* indicates whether the individual teacher or caregiver reported that he/she was Hispanic. If there was no information for a respondent on the Hispanic ethnicity question, they were coded as non-Hispanic black or white according to their selection on the race variable. Individuals who are not black, white, or Hispanic were omitted from this analysis, as were those who refused to answer the race and Hispanic ethnicity question (n=487 center-based; 476 listed, home-based; and n=138 unlisted, home-based). Accordingly, the sample for this analysis is limited to 4,931 center-based; 3,413 listed, home-based; and 1,793 unlisted, home-based teachers or caregivers.

Nativity status indicates whether the teacher or caregiver was U.S.- or foreign-born. Some respondents refused to answer or reported that they did not know (n=210 center-based; 80 listed, home-based; and 11 unlisted, home-based), resulting in a valid sample for analysis of this variable of 5,195 center-based; 3,792 listed, home-based; and 1,908 unlisted, home-based teachers or caregivers.

Education indicates whether the teacher or caregiver earned a Bachelor’s degree or a higher degree. A small number of cases were omitted from this analysis because the teacher or caregiver refused to answer, reported that they did not know, or provided a response that could not be categorized, resulting in a valid sample of 5,386 center-based; 3,727 listed, home-based; and 1,904 unlisted, home-based teachers or caregivers. (We focused on Bachelor’s degree or higher because regulations and standards for publicly funded staff increasingly require attainment of this level of education. The results are similar across different categorizations of educational level.)

College major indicates that teachers or caregivers reported having an ECE or education-related major. Respondents were only asked about their major if they had completed some college or more, resulting in a valid sample of 4,391 center-based and 2,153 listed, home-based teachers or caregivers. Unlisted, home-based teachers or caregivers were not asked this question and were omitted from this analysis.

Child Development Associate (CDA) or state certification for early care and education/school-age care indicates whether the individual teacher or caregiver has a CDA or state certification or endorsement for early care and education/school-age care. Listed and unlisted home-based teachers or caregivers who reported caring only for children with whom they had a prior relationship (e.g., neighbors, relatives, friends, etc.) were not asked this question (n=342 listed; n=1,805 unlisted). Additionally, some respondents refused to answer or did not know the answer to this question. This resulted in a valid sample of 5,167 center-based; and 3,370 listed, home-based providers. We excluded unlisted, home-based teachers or caregivers for this variable because the analytic sample was restricted to 235 cases.

Work experience indicates whether the teacher or caregiver has cared for children under age 13 for five or fewer years, more than five years and up to 10 years, or more than 10 years. A small number of cases across the three teacher or caregiver types were omitted because the respondent refused to answer or reported “did not know” (these categories included two center-based; 90 listed, home-based; and 34 unlisted, home-based teachers or caregivers). An additional 39 listed, home-based and 34 unlisted, home-based teachers or caregivers were omitted because the question was “not applicable” to them; no additional information is available on these cases. This resulted in a valid sample for this variable of 5,393 center-based; 3,747 listed, home-based; and 1,888 unlisted, home-based cases.

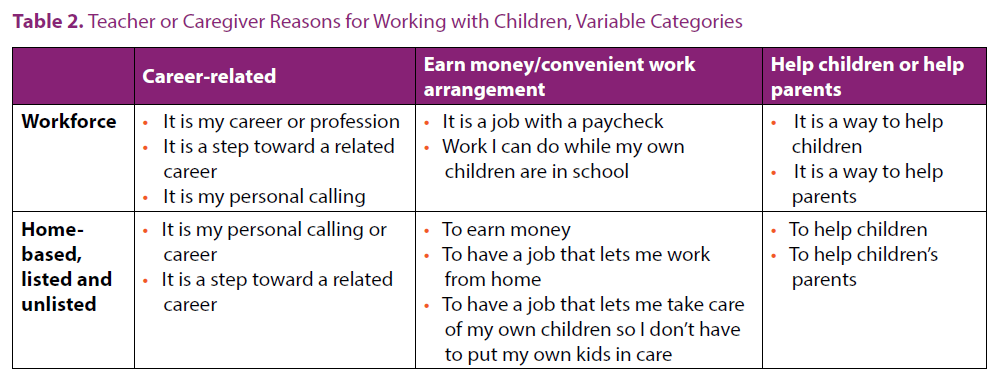

Reason for working with children refers to the primary reason teachers or caregivers offered for working with children. Response options for home-based (listed and unlisted) teachers or caregivers are somewhat different than for workforce staff. Table 2 shows the following categories for home-based teachers or caregivers: career-related reasons; to earn money or because it is a convenient work arrangement; and to help children or to help parents. A small number of cases were omitted from this analysis because respondents refused to answer or did not know the answer (n=129 center-based; 269 listed, home-based; and 17 unlisted, home-based), resulting in a valid sample of 5,269 center-based; 3,612 listed, home-based; and 1,903 unlisted, home-based teachers or caregivers.

Analysis

We conducted descriptive analyses on selected characteristics of the workforce, by type of teacher or caregiver and the proportion of Hispanic children served. These results are highlighted in Figures 1 through 5; the full set of results is shown in Table 3. All analyses were conducted in STATA and were weighted to be nationally representative of home-based teachers or caregivers, or center-based classroom staff. The sample weights for listed and unlisted home-based teachers or caregivers vary substantially, so we analyzed these two groups separately, as suggested in the codebook.26 The listed, home-based sample was selected from a sample frame of all listed, home-based teachers or caregivers in an available geographic cluster area, while the unlisted sample was selected from anchor census tracts within each geographic cluster. The sample weight accounts for these differences. Analyses are presented with significant differences at the p=.05 level or less noted by proportion of Hispanic children served (high vs. low Hispanic density) within teacher or caregiver type. The datasets were not combined, so tests of significance were not analyzed across teacher or caregiver types.

Findings

Teachers and caregivers working in high-Hispanic-serving settings are more likely to be Hispanic than their counterparts working in low-Hispanic-serving settings.f,g Forty-five percent of teachers or caregivers working in high-Hispanic-serving centers—and roughly two-thirds in high-Hispanic-serving home-based settings—are Hispanic (see Figure 1). In sharp contrast, just 2 to 6 percent of teachers and caregivers in low-Hispanic-serving settings are Hispanic (see Table 3).

Among those working in high-Hispanic-serving settings, 15 percent of center-based; 10 percent of listed, home-based; and 6 percent of unlisted, home-based teachers or caregivers are non-Hispanic black (results not shown). Across the three teacher or caregiver types, 25 to 40 percent of those in high-Hispanic-serving settings are non-Hispanic white.

Many teachers or caregivers working in high-Hispanic-serving centers and large, listed, home-based settings speak Spanish with children; they are more likely to do so than their peers in low-Hispanic-serving settings. Among those working in high-Hispanic-serving settings, 22 percent in centers; 56 percent of listed, home-based teachers or caregivers;h and 42 percent of the unlisted, home-based workforce speak Spanish with children (see Figure 1).i

The opposite pattern is found among low-Hispanic-serving settings, where few teachers or caregivers speak Spanish with the children they serve.

Most teachers or caregivers were born in the United States, but those working in high-Hispanic-serving settings are more likely to have been born in another country, relative to those working in low-Hispanic-serving settings (see Table 3). Among high-Hispanic-serving teachers or caregivers, 77 percent of those employed in centers; 49 percent of those in listed, home-based settings; and 66 percent of those in unlisted, home-based settings are U.S-born. This is significantly lower than their counterparts who serve a low proportion of Hispanic children (92, 91, and 95 percent, respectively).

Teachers and caregivers working in high-Hispanic-serving centers have as much or more education than their peers in low-Hispanic-serving centers (see Figure 2). Regardless of the proportion of Hispanic children served, roughly one-third of teachers or caregivers working in centers have a Bachelor’s degree or higher. However, teachers or caregivers working in high-Hispanic-serving centers are more likely to have a CDA or state certification (see Figure 3); if they have attended college, they are more likely to have a major relevant to ECE than their peers working in low-Hispanic-serving centers (see Figure 4).

A somewhat mixed picture emerges when we look at home-based teachers and caregivers. Overall, most listed and unlisted home-based teachers or caregivers—regardless of the proportion of Hispanic children served—lack a Bachelor’s degree (see Table 3). However, among listed, home-based teachers or caregivers, those serving a low proportion of Hispanic children are more likely to have a Bachelor’s degree than those serving a high proportion (20 and 16 percent, respectively). If they do have a degree, high- and low-Hispanic serving listed, home-based teachers or caregivers are equally likely to have a major relevant to ECE (see Figure 4).j More than half of listed, home-based teachers or caregivers serving a high proportion of Hispanic children have a CDA or state certification (see Figure 3). These percentages are higher than among those serving a low proportion of Hispanic children.

Teachers or caregivers in both high- and low-Hispanic-serving settings have comparable years of experience working with children. Regardless of Hispanic density, the majority of center-based and listed, home-based teachers or caregivers had more than 10 years of experience; few have worked with children for five or fewer years. In contrast, few (27 percent among high-Hispanic-serving and 31 percent among low-Hispanic serving) unlisted, home-based teachers or caregivers have more than 10 years of experience, and roughly half have been working with children for five or fewer years (see Table 3). Unlisted, home-based providers include relatives, friends, and neighbors who care for children.

Teachers or caregivers in high-Hispanic-serving settings are as likely as their counterparts in low-Hispanic-serving settings to think of their work with children as a career. Among those working with a high proportion of Hispanic children, 70 percent of those in centers; 48 percent of listed, home-based teachers or caregivers; and 9 percent of unlisted, home-based teachers or caregivers reported that their main reason for working with young children is that they consider it a career. The percentages among those in low-Hispanic-serving settings were comparable (see Table 3).

Compared with their low-Hispanic-serving counterparts, teachers or caregivers working in high-Hispanic-serving centers are more likely to report that their main reason for working with children is a desire to help children/parents (27 vs. 21 percent), and are less likely to report being motivated by the paycheck or convenient hours (3 vs. 6 percent; see Figure 5). A similar pattern is seen among those in high-Hispanic-serving, unlisted settings: Compared to their low-Hispanic-serving counterparts, they are more likely to report working with children to help them and their parents (87 vs. 81 percent), and less likely to report being motivated by earnings or the flexible work arrangement (3 vs. 7 percent). No differences were seen among listed, home-based teachers or caregivers serving a high or low proportion of Hispanic children; among high- and low-Hispanic-serving teachers or caregivers, roughly one in four reported working with children to help children and parents. Twenty-eight percent of listed, home-based teachers or caregivers reported working with children for the money or flexible work arrangement.

Summary and Implications

This brief presents the first national portrait of ECE teachers and caregivers in settings that serve a large proportion of Hispanic children, focusing on features of ethnic and linguistic diversity; education, training, and experience; and motivation for caring for children. We find several promising patterns.

Overall, close to half of teachers and caregivers who work in high-Hispanic-serving centers—and roughly two-thirds of home-based teachers and caregivers serving a large proportion of Hispanic children—are Hispanic. Past research suggests that the racial/ethnic makeup of teachers and caregivers may play a role in parents’ child care selection.27,28 More generally, a more racially, ethnically, and linguistically diverse ECE workforce may provide a sense of comfort or familiarity to families who are racial/ethnic minorities, especially for recent immigrants.13,29

One finding is especially important for families whose primary language is Spanish: Many teachers and caregivers in high-Hispanic-serving ECE settings speak Spanish with the children they serve. This is true for the majority of teachers and caregivers in high-Hispanic-serving centers and many of those in large, home-based settings. Additionally, one in five teachers or caregivers working in centers with a low proportion of Hispanic children also speak Spanish, although few home-based, low-Hispanic-serving teachers or caregivers do the same. Few teachers or caregivers who serve a small proportion of Hispanic children are Hispanic themselves and few speak Spanish to the children they serve, which may not bode well for the recruitment of Hispanic families; it may also reflect (or inadvertently result in) a segregated ECE market.30 Interestingly, the data also suggest that centers serving a large proportion of Hispanic children may be effectively recruiting not only Latino staff, but also Spanish speakers of non-Hispanic descent. For example, while just 45 percent of center staff serving a large percentage of Hispanic children are Hispanic, 64 percent speak Spanish with the children they serve.

One important avenue for future research is to gain a better understanding of how centers recruit, and of the challenges they face in recruiting a diverse workforce. It will also be important to understand how two- and four-year college degree programs are developing and mentoring upcoming ECE staff, as well as what steps, if any, are being taken to increase the diversity of the ECE workforce. Future research must also improve the match between the data available on children and that available for staff. In the NSECE, data on the racial/ethnic composition of children was collected at the center level, so we do not know the racial/ethnic composition of a randomly selected staff member’s classroom. For example, it is possible (although still unlikely) that Spanish-speaking staff who work in high-Hispanic-serving centers serve few or no Hispanic children. Our earlier research found that Hispanic children make up the majority of children in nearly half of high-Hispanic-serving centers.31

Those teachers or caregivers who work with a high proportion of Hispanic children have similar or higher levels of training, education, and experience than those working in low-Hispanic-serving settings. On the other hand, most center staff lack a Bachelor’s degree, as do most home-based teachers or caregivers. This underscores an area for improvement and an added challenge for ECE providers. Notably, we find that the majority of those serving a large proportion of Hispanic children in centers and in listed, home-based settings have a CDA or state certification. This is higher than the percentage for those serving a smaller proportion of Hispanic children, and may be due in part to public funding, which has specific educational requirements for teachers. In fact, we find that high-Hispanic-serving centers—like Head Start or public pre-K, which have specific requirements for teacher training—are more likely than their counterparts to receive public funding.

Overall, our findings indicate that teachers and caregivers in high-Hispanic-serving settings fare better on our indicators of interest (e.g., they are more likely to have a CDA or state certification and a relevant major, if they attended college; more racially, ethnically, and linguistically diverse; less likely to report caring for children for the paycheck; etc.). Nevertheless, the majority of ECE teachers or caregivers are home-based, and many Hispanic children are in relative and friend care—especially infants and toddlers. More outreach and training opportunities may be needed to enhance the quality of care for this important segment of teachers and caregivers.

About This Brief

This brief is part of an ongoing series aimed at better understanding the early care and education experiences of Latino children, as well as the access, availability, and use of early care and education in Latino communities. Earlier briefs examined predictors of quality and indicators of flexibility and availability among high-Hispanic-serving settings; the care and work schedules of Hispanic children and parents; parental preferences for (and search processes and decision-making related to) ECE; and national patterns of early care use among Hispanic children in the United States. This and other briefs in the series use data from the 2012 National Survey of Early Care and Education (NSECE)—a set of four integrated, nationally representative surveys that describe the early care and education landscape in the United States.

Related briefs

Notes

a In this brief, we use the terms Hispanic and Latino interchangeably.

b For simplicity, we refer to these three types of teachers or caregivers as the ECE workforce, although we recognize that many are unpaid or would not consider themselves to be in the workforce because of the care they provide for children.

c Some teachers or caregivers serving children ages 0 to 5 also serve school-aged children.

d We use 25 percent as the cut-off for two reasons. First, 1 in 4 children in the United States today is Hispanic.1 Second, higher cut-offs would result only in the inclusion of teachers or caregivers serving communities with large densities of Hispanics, and thus would result in the exclusion of teachers or caregivers serving less dense—and possibly newer—Hispanic communities.21,22

e To prevent disclosure of respondents’ identities, only home-based providers serving four or more children were asked about the language they speak with the children they serve.

f While the same pattern was observed between high- and low-Hispanic-serving unlisted, home-based teachers or caregivers, the differences were not statistically significant.

g In the NSECE, center-based staff reported on their individual traits and experiences, but data on the ethnic composition of children served were collected at the overall center level. For example, it is possible that teachers or caregivers who are themselves Hispanic, or who speak Spanish with children and work in a high-Hispanic-serving center, may not have any Hispanic children in their individual classroom. This limitation of the data applies not only to the features of ethnic and linguistic diversity, but also to teachers’ or caregivers’ level of education, experience, and motivation for providing ECE.

h Among home-based teachers and caregivers, only those serving four or more children were asked what language they usually speak with the children they serve.

i Differences between teachers or caregivers in high- and low-Hispanic-serving unlisted, home-based settings were not significant, likely due to the small sample size.

j Unlisted, home-based teachers or caregivers were not asked about their major.

Suggested Citation:

Guzman, L., Hickman, S., Turner, K., & Gennetian, L. A. (2018). Who is caring for Latino children? The characteristics of the early care and education teachers and caregivers serving a high proportion of Hispanic children. National Research Center on Hispanic Children & Families. https://doi.org/10.59377/412g2522a

References

1 Federal Interagency Forum on Child and Family Statistics. (2017). America’s children: Key national indicators of well-being, 2017, Table POP3. Washington DC: U.S. Government Printing Office. From http://www.childstats.gov/americaschildren/tables.asp

2 Child Trends Databank. (2016). Racial and ethnic composition of the child population. Bethesda, MD: Child Trends. From http://www.childtrends.org/?indicators=racial-and-ethnic-composition-of-the-child-population

3 Murphey, D., Madill, R., & Guzman, L. (2017). Making math count more for young Latino children. Bethesda, MD: Child Trends. Retrieved From https://www.childtrends.org/publications/making-math-count-young-latino-children

4 Child Trends Databank. (2015). Early school readiness: Indicators of child and youth well-being. Bethesda, MD: Child Trends. From https://www.childtrends.org/indicators/early-school-readiness

5 Gormley, W. T., Phillips, D., & Gayer, T. (2008). Preschool programs can boost school readiness. Science, 320(5884), 1723.

6 Gormley Jr, W. T., Gayer, T., Phillips, D., & Dawson, B. (2005). The effects of universal pre-K on cognitive development. Developmental Psychology, 41(6), 872.

7 Gormley, W. T., Phillips, D. A., Newmark, K., Welti, K., & Adelstein, S. (2011). Social‐emotional effects of early childhood education programs in Tulsa. Child Development, 82(6), 2095-2109.

8 Loeb, S., Bridges, M., Bassoka, D., Fuller, B., & Rumberger, R. (2007). How much is too much? The influence of preschool centers on children’s social and cognitive development. Economics of Education Review, 26, 52-66.

9 Institute of Medicine and National Research Council. (2012). The early childhood care and education workforce: Challenges and opportunities. Washington, DC: The National Academies Press.

10 Yamauchi, L., Im, S., Lin, C., & Schonleber, N. (2013). The influence of professional development on changes in educators’ facilitation of complex thinking in preschool classrooms. Early Child Development and Care, 183(5), 689-706.

11 Downer, J. T., Goble, P., Myers, S. S., & Pianta, R. C. (2016). Teacher-child racial/ethnic match within pre-kindergarten classrooms and children’s early school adjustment. Early Childhood Research Quarterly, 37, 26-38.

12 Howes, C., & Shivers, E. M. (2006). New child–caregiver attachment relationships: Entering childcare when the caregiver is and is not an ethnic match. Social Development, 15(4), 574-590.

13 Burchinal, M., & Cryer, D. (2004). Diversity, child care quality, and developmental outcomes. Early Childhood Research Quarterly, 18(4), 401-426.

14 Son, S. H. C., Kwon, K. A., Jeon, H. J., & Hong, S. Y. (2013). Head Start classrooms and children’s school readiness benefit from teachers’ qualifications and ongoing training. Child & Youth Care Forum, 42(6), 525-553.

15 Han, J., & Yin, H. (2016). Teacher motivation: Definition, research development and implications for teachers. Cogent Education, 3(1).

16 National Survey of Early Care and Education Project Team. (2015). Measuring predictors of quality in early care and education settings in the National Survey of Early Care and Education. Washington, DC: Office of Planning, Research and Evaluation, Administration for Children and Families, U.S. Department of Health and Human Services. From https://www.acf.hhs.gov/sites/default/files/documents/opre/measuring_predictors_of_quality_mpoq_in_the_nsece_final_092315_b508.pdf

17 Guzman, L., Forry, N., Zaslow, M., Kinukawa, A., Rivers, A., Witte, A., et al. (2009). Design phase: National study of child care supply and demand—2010. Washington, DC: Office of Planning, Research and Evaluation. From https://www.acf.hhs.gov/sites/default/files/documents/opre/literature_review.pdf

18 Doherty, G., Forer, B., Lero, D. S., Goelman, H., & LaGrange, A. (2006). Predictors of quality in family child care. Early Childhood Research Quarterly, 21(3), 296-312.

19 Howes, C., Shivers, E. (2006). New childcaregiver attachment relationships: Entering childcare when the caregiver is and is not an ethnic match. Social Development, 15, 574-590.

20 Calzada, E. J., Huang, K.-Y., Hernandez, M., Soriano, E., Acra, C. F., Dawson-McClure, S., et al. (2015). Family and teacher characteristics as predictors of parent involvement in education during early childhood among Afro-Caribbean and Latino immigrant families. Urban Education, 50(7), 870-896.

21 Helms, H., Hengstebeck, N. D., Rodriguez, Y., Mendez, J., & Crosby, D. A. (2015). Mexican immigrant family life in a pre-emerging southern gateway community. Bethesda, MD: National Research Center on Hispanic Children & Families. From http://www.childtrends.org/?publications=mexican-immigrant-family-life-in-a-pre-emerging-southern-gateway-community

22 Turner, K., Wildsmith, E., Guzman, L., & Alvira-Hammond, M. (2016). The changing geography of Hispanic children and families. Bethesda, MD: National Research Center on Hispanic Children & Families. From https://hispanicrescen.wpengine.com/publications/the-changing-geography-of-hispanic-children-and-families/

23 National Survey of Early Care and Education Project Team. (2013). Number and characteristics of early care and education (ECE) teachers and caregivers: Initial findings from the National Survey of Early Care and Education (NSECE). Washington, DC: Office of Planning, Research and Evaluation, Administration for Children and Families, U.S. Department of Health and Human Services. From https://www.acf.hhs.gov/sites/default/files/documents/opre/nsece_wf_brief_102913_0.pdf

24 National Survey of Early Care and Education Project Team. (2012). National Survey of Early Care and Education (NSECE), 2012. Ann Arbor, MI: Inter-University Consortium for Political and Social Research. From https://www.childandfamilydataarchive.org/cfda/archives/cfda/studies/35519

25 Cheng, I., Koralek, R., Robinson, A., Russell, S., Schwartz, D., & Sarna, M. (2018). Career pathways in early care and education. Bethesda, MD: Abt Associates. From https://www.dol.gov/asp/evaluation/completed-studies/Career-Pathways-Design-Study/4-Career-Pathways-in-Early-Care-and-Education-Report.pdf

26 National Survey of Early Care and Education Project Team. (2012). NSECE codebook for Home-based Public-Use Data file. National Opinion Research Center. From https://www.childandfamilydataarchive.org/cfda/archives/cfda/studies/35519

27 Benner, A. D., & Yan, N. (2015). Classroom race/ethnic composition, family-school connections, and the transition to school. Applied developmental science, 19(3), 127-138.

28 Forry, N., Tout, K., Rothenberg, L., Sandstrom, H., & Vesely, C. (2013). Child care decision-making literature review. Washington, DC: Office of Planning, Research and Evaluation. From https://www.acf.hhs.gov/sites/default/files/documents/opre/child_care_decision_making_literature_review_pdf_version_v2.pdf

29 Reid, J., & Kagan, S. (2015). A better start why classroom diversity matters in early education. New York, NY: The Century Foundation and the Poverty & Race Research Action Council. From https://s3-us-west-2.amazonaws.com/production.tcf.org/app/uploads/2015/04/29222920/A_Better_Start-11.pdf

30 Kashen, J., Potter, H., & Stettner, A. (2016). Quality jobs, quality child care: The case for a well-paid, diverse early education workforce. New York, NY: The Century Foundation. From https://s3-us-west-2.amazonaws.com/production.tcf.org/app/uploads/2016/06/14145046/quality-jobs-quality-child-care.pdf

31 Guzman, L., Hickman, S., Turner, K., & Gennetian, L. (2017). How well are early care and education providers who serve Hispanic children doing on access and availability? Bethesda, MD: National Research Center on Hispanic Children & Families. From https://hispanicrescen.wpengine.com/publications/how-well-are-early-care-and-education-providers-who-serve-hispanic-children-doing-on-access-and-availability/