Mar 22, 2023

Research Publication

Characteristics of the Early Childhood Workforce Serving Latino Children

Authors:

Introduction

High-quality early care and education (ECE) experiences are critical for children’s development, and evidence shows that Latinoa children—especially those from Spanish-speaking and immigrant households—often benefit more from these opportunities than their peers.1 Given the central role that teachers and caregivers play in shaping ECE quality, knowledge about this segment of the workforce can help inform workforce development initiatives and policy efforts to increase Hispanic children’s access to high-quality early childhood experiences.2

To provide a national profile of the U.S. ECE workforce serving Latino families and their children, we use data from the 2019 National Survey of Early Care and Education3 (NSECE) to describe key demographic and professional characteristics of teachers and caregivers serving young children, from birth to age 5, in center- and home-based settings. Specifically, we compare several characteristics—ethnic and linguistic diversity, education and training, work experience, and professional development—of early childhood teachers and caregiversb in high-Hispanic-serving settings, where Hispanic children make up 25 percent or more of total enrollment, to those in low-Hispanic-serving settings, where Hispanic enrollment is below 25 percent. We also compare these characteristics of the ECE workforce in high- and low-Hispanic-serving settings in 2019, just prior to the global COVID-19 pandemic, to those from an earlier report on similar data from the 2012 NSECE.

About this brief

This report draws on nationally representative data from the 2019 National Survey of Early Care and Education (NSECE) to describe multiple aspects of child care access and utilization for children in low-income Latino families, including the availability, flexibility, and affordability of care, as well as the characteristics of settings and providers who serve Hispanic children. These descriptive analyses update similar analyses focused on ECE access for Hispanic families with young children that drew from the 2012 NSECE. For more information, readers are encouraged to review other fact sheets in this series, as well as our synthesis on child care access for Hispanic families.

Key Findings

Similar to results from 2012, we find that early childhood teachers and caregivers in high-Hispanic-serving settings were more likely than those in low-Hispanic-serving settings to possess characteristics that could facilitate high-quality ECE experiences, including 1) greater representation of Hispanic ethnicity, bilingual skills, and personal experiences of immigration; 2) higher rates of early childhood credentialing; 3) higher receipt of mentored professional development; and 4) higher rates of working in a publicly funded ECE setting.

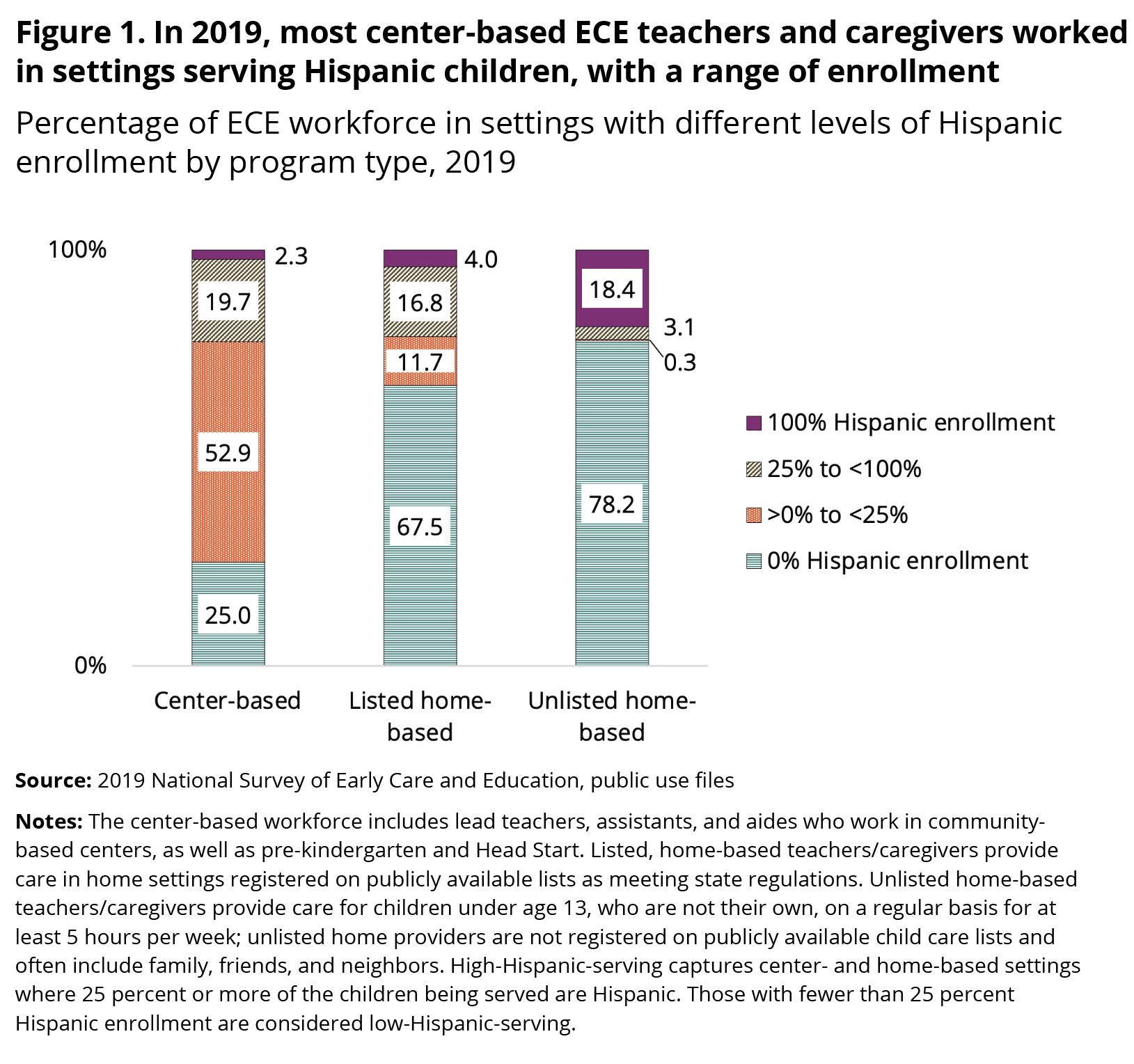

- In 2019, most center-based teachers and caregivers (75%) worked in programs serving one or more Hispanic children, and 1 in 5 worked in settings with high Hispanic enrollment (25% or above). In contrast, most home-based teachers and caregivers reported having no Hispanic children enrolled, although the share who were high-Hispanic-serving (1 in 5) parallels that for the center-based workforce. This distribution of the ECE workforce across high- and low-Hispanic-serving settings is similar to what it was in 2012.

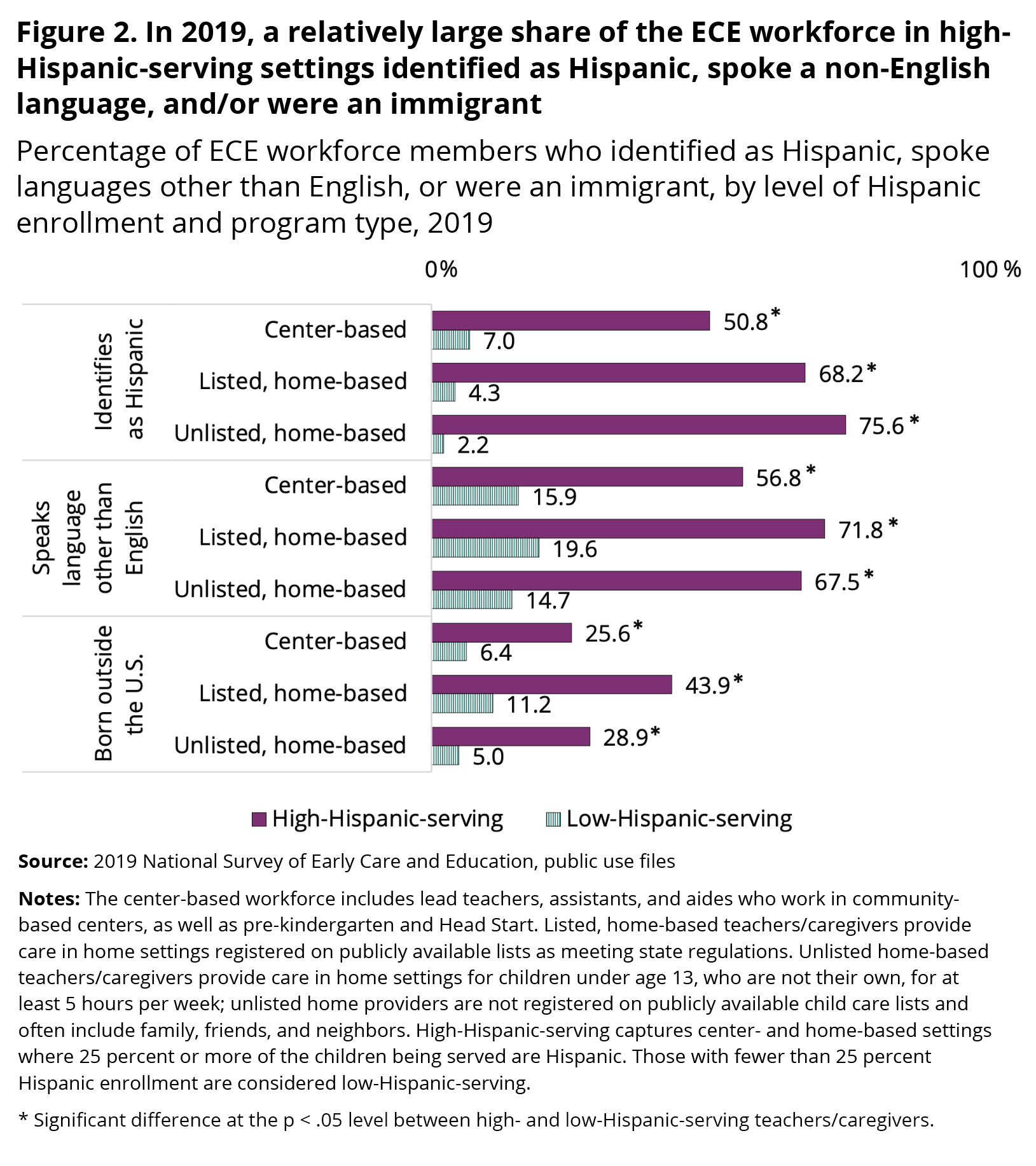

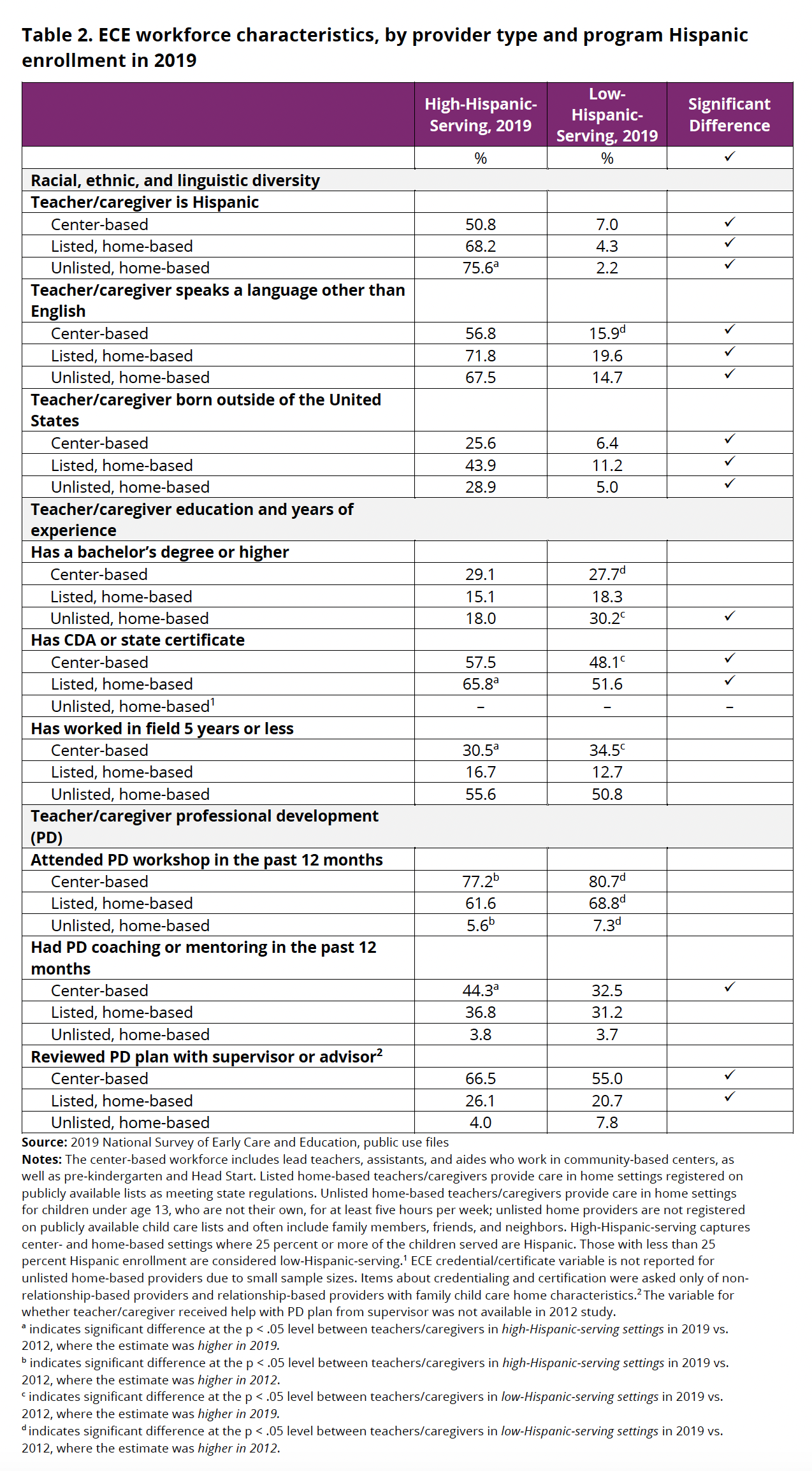

- Many teachers and caregivers working in high-Hispanic-serving settings had ethnic and linguistic backgrounds reflective of the Hispanic families they serve. Approximately half identified as Latino, just over half spoke a language other than English, and at least one quarter were foreign-born. A smaller percentage of the workforce in low-Hispanic-serving settings had these characteristics.

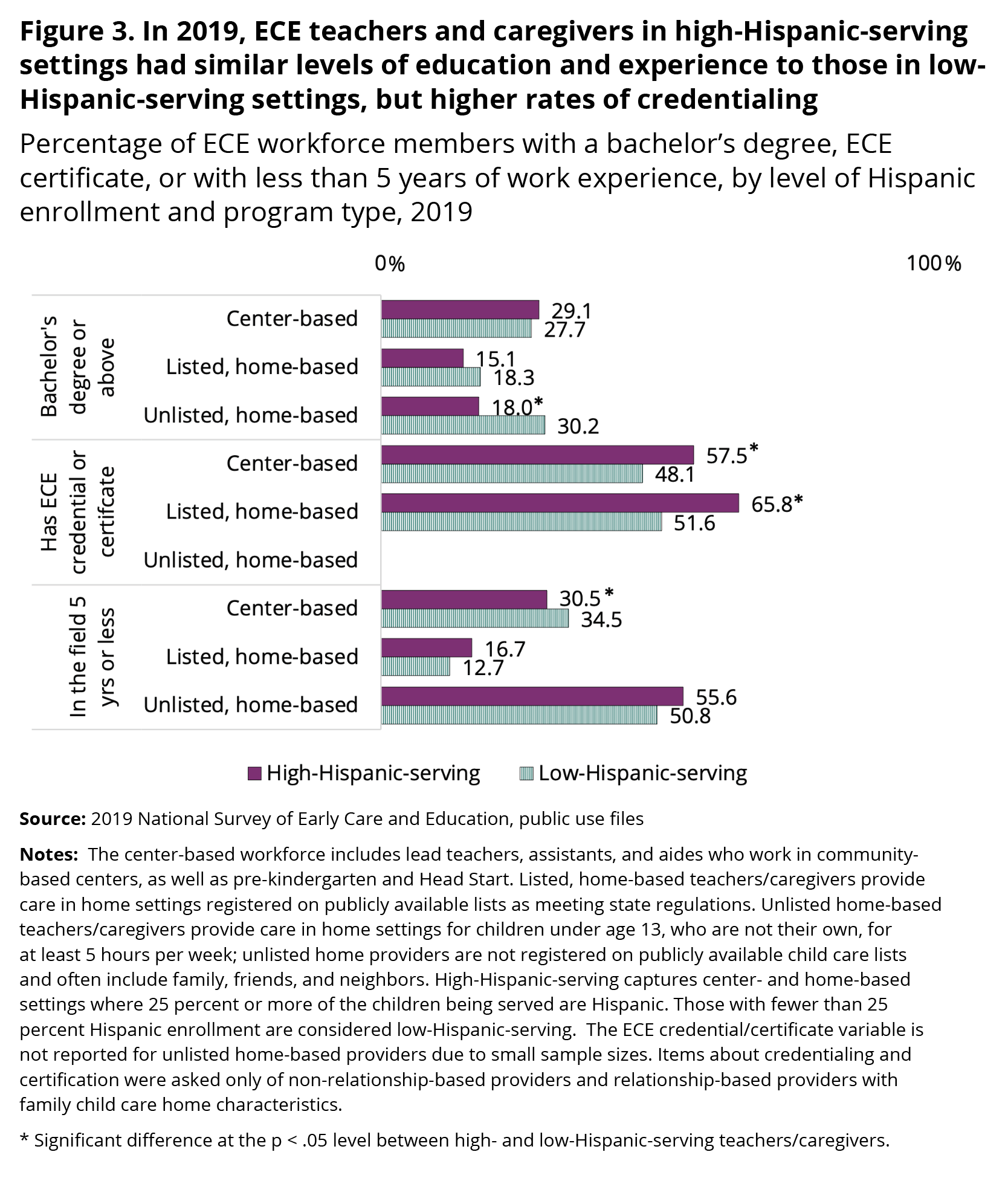

- Average levels of workforce education and professional experience were generally similar across high- and low-Hispanic-serving settings. However, a larger share of teachers and caregivers in high-Hispanic-serving settings had a child development credential or certificate compared to their peers in low-Hispanic-serving centers and homes.

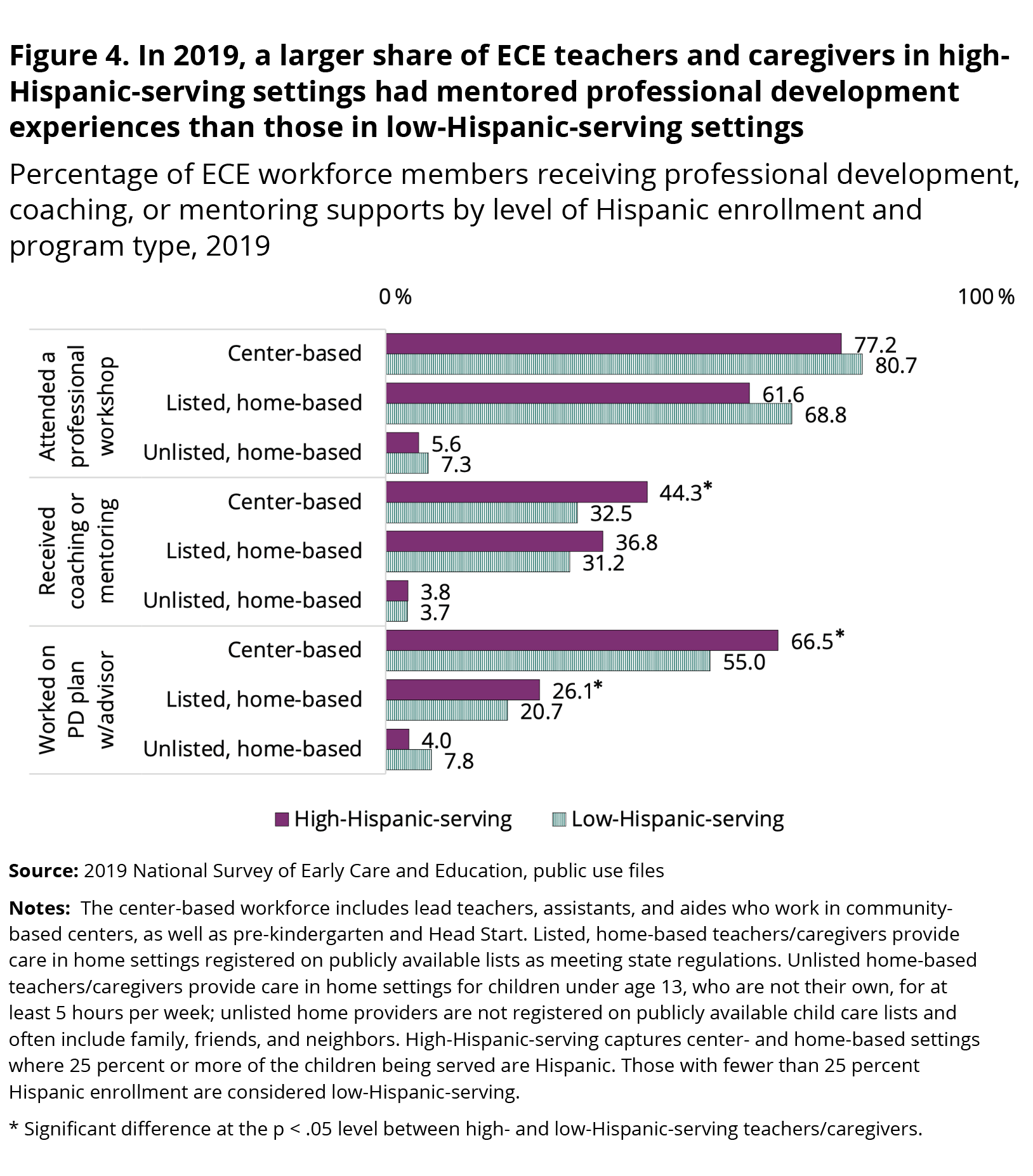

- A larger share of the high-Hispanic-serving ECE workforce engaged in professional development activities, such as working with a mentor or coach, relative to the workforce in low-Hispanic-serving settings. Very few unlisted home-based providers (primarily composed of family members, friends, and neighbors), in either high- or low-Hispanic-serving settings, reported professional development in the prior 12 months.

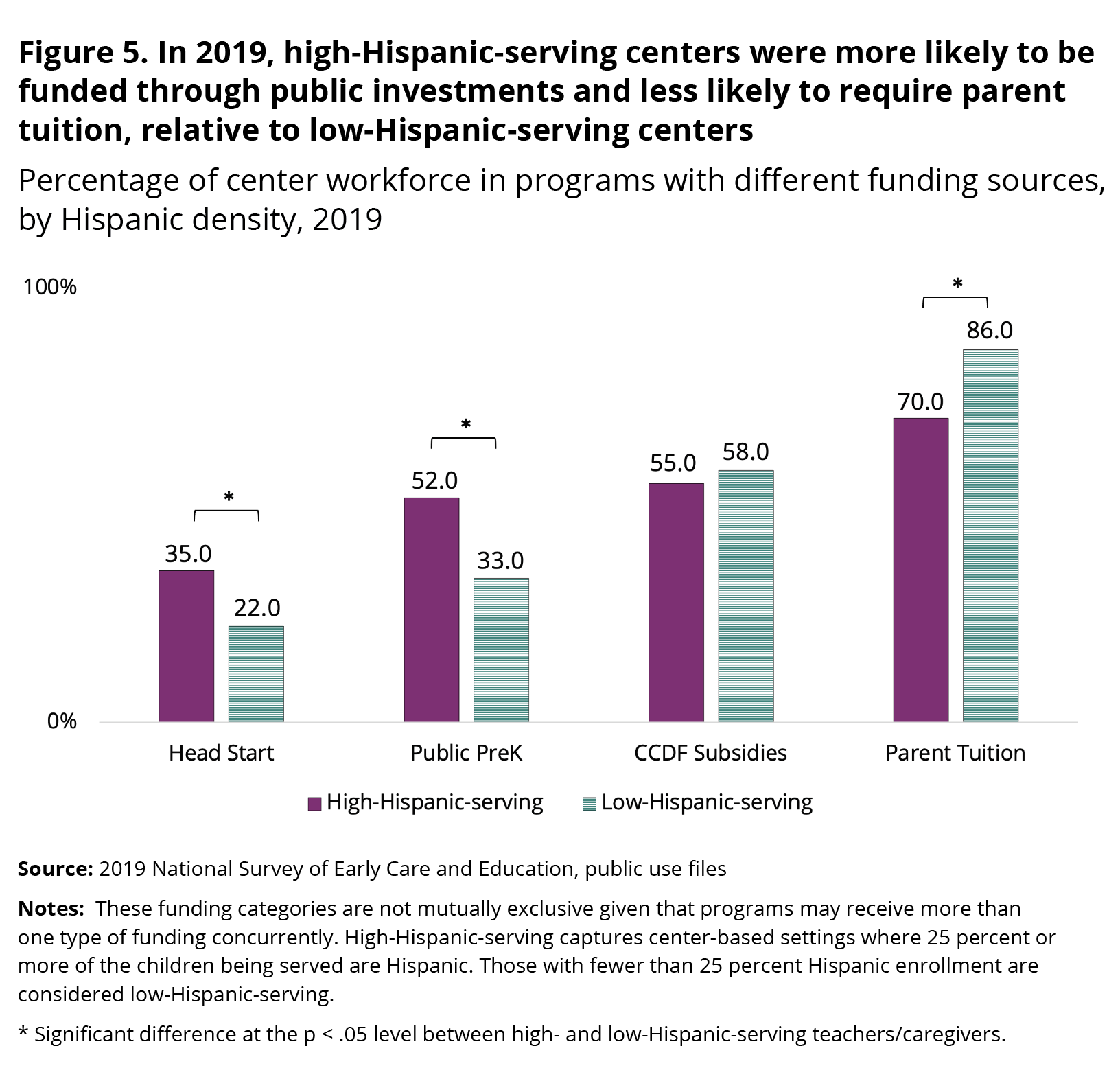

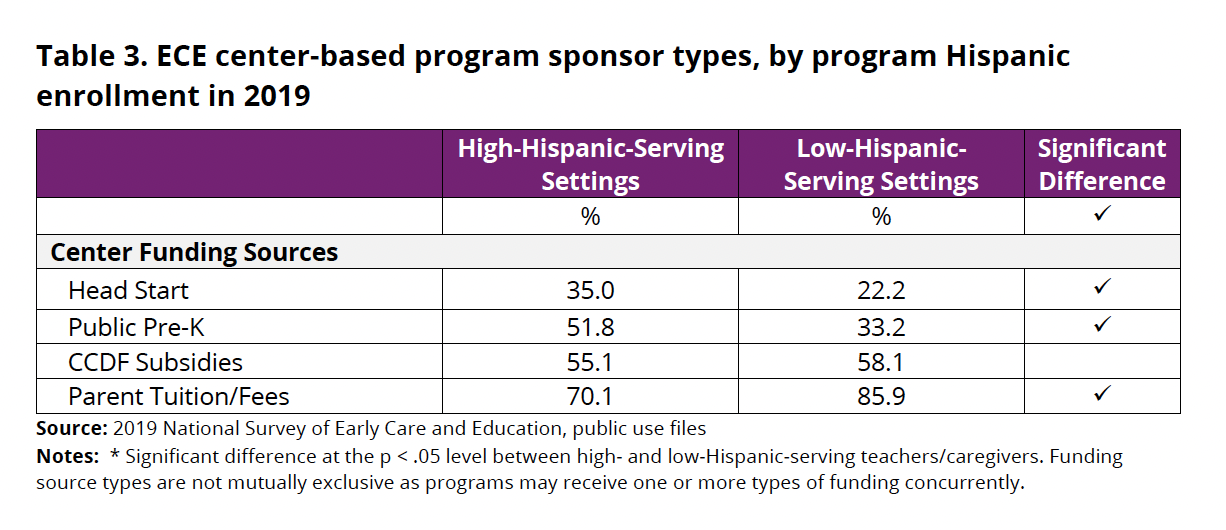

- Compared to their peers in low-Hispanic-serving centers, a larger share of high-Hispanic-serving teachers and caregivers worked in centers receiving public funding from Head Start and/or public Pre-K, and a smaller share worked in centers receiving private tuition from parents.

ONE IN FIVE ECE PROFESSIONALS WORKED IN HIGH-HISPANIC SERVING SETTINGS IN 2019

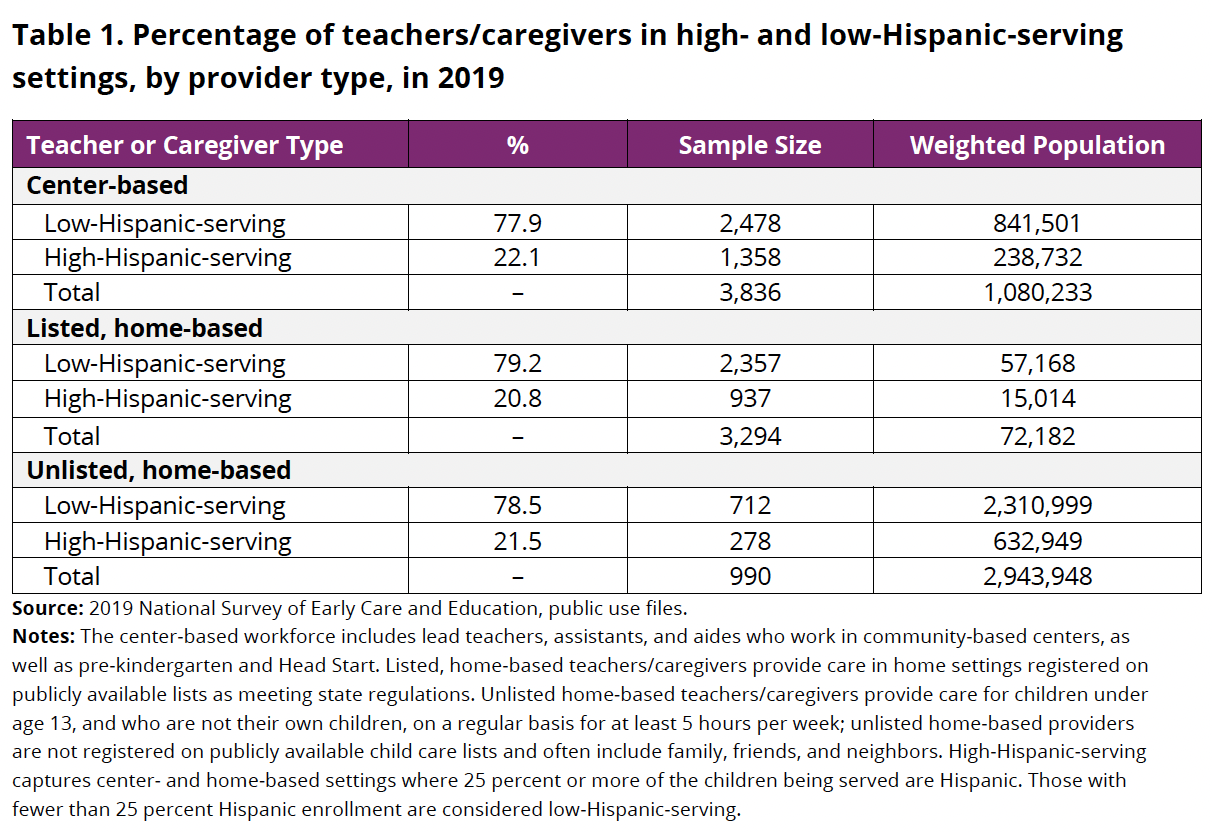

In 2019, roughly one fifth of the early childhood workforce worked in either a center- or home-based setting that served a high percentage of Hispanic children. Using program-reported enrollment information, we categorized settings as high-Hispanic-serving if their enrollment of Hispanic children was at or above 25 percent, and as low-Hispanic-serving if their Hispanic enrollment was less than 25 percent.c, 4 We found that approximately 1 in 5 center-based, listed home-based, and unlisted home-based teachers and caregivers worked in a high-Hispanic-serving setting (Table 1).d

As shown below in Figure 1, some settings categorized as low-Hispanic-serving had no Hispanic children enrolled at the time of the survey (0% Hispanic enrollment); likewise, some settings categorized as high-Hispanic-serving had only Hispanic children enrolled (100% Hispanic enrollment). Examining type of care, we find that a majority (77.9%) of the 2019 center-based workforce worked in a program with one or more Hispanic children enrolled. In contrast, a majority of listed (67.5%) and unlisted (78.2%) 2019 home-based providers reported not serving any Hispanic children. Unlisted home-based settings were segregated on Hispanic density; providers who served any Hispanic children tended to have 100 percent Hispanic enrollment.

The remainder of this report compares workforce characteristics across the broader categories of high- and low-Hispanic-serving settings.

ECE WORKFORCE BY HISPANIC ETHNICITY, LANGUAGE, AND NATIVITY

A larger percentage of teachers and caregivers in high-Hispanic-serving ECE settings identified as Hispanic, spoke a language other than English, and were foreign-born, compared to those in low-Hispanic serving settings (Figure 2). Fifty to 60 percent of the ECE workforce in high-Hispanic-serving settings identified as Hispanic and/or spoke a language other than English, a larger share than among the workforce in low-Hispanic-serving settings. In addition, although the majority of the ECE workforce in both centers and homes in 2019 were U.S.-born, those in high-Hispanic-serving settings were more likely to have been born outside the United States than those in low-Hispanic-serving settings.

ECE WORKFORCE BY EDUCATION, TRAINING, AND YEARS OF EXPERIENCE

In 2019, teacher/caregiver education and experience levels were generally similar across high- and low-Hispanic-serving settings. However, a larger share of the workforce in high-Hispanic-serving settings had a child development credential or certificate than those in low-Hispanic-serving settings (Figure 3). Overall, less than one third of ECE teachers and caregivers, regardless of their care settings’ level of Hispanic enrollment, had a bachelor’s degree. In addition, high-Hispanic-serving, unlisted home-based providers had lower rates of four-year degree attainment than those serving few or no Hispanic children. Roughly half of teachers and caregivers in centers and listed homes had a child development credential or certificate, with higher rates reported by those in high- than in low-Hispanic-serving settings. Years of experience in the field did not vary significantly by level of Hispanic enrollment, but rather by type of setting. Many unlisted home-based teachers and caregivers reported being new to the field, with nearly half having five or fewer years of experience. On the other hand, fewer than one third of the center- and listed home-based workforce were new to the field.

ECE WORKFORCE BY PROFESSIONAL DEVELOPMENT ACTIVITIES

Teachers and caregivers in high-Hispanic-serving settings were as likely, or more likely, to engage in professional development than those in low-Hispanic-serving settings (Figure 4). Most of the ECE workforce in centers and listed homes—but very few in unlisted homes—reported attending a workshop in the past year to improve their skills for working with children, with no significant differences by program level of Hispanic enrollment. However, teachers and caregivers in high-Hispanic-serving settings were more likely than those in low-Hispanic-serving settings to have received mentored professional development in the form of coaching (among the center-based workforce), or to have reviewed their professional development plans with a mentor or supervisor (among the center and listed home-based workforces).

CENTER-BASED ECE WORKFORCE BY PROGRAM SPONSORSHIP TYPE

Center-based programs serving high and low percentages of Hispanic children differ on the types of funding they receive. Because some observed workforce differences between high- and low-Hispanic-serving settings may relate to differences in program sponsorship type, we examined whether centers’ receipt of public and private funding varied by their level of Hispanic enrollment. We found that high-Hispanic-serving centers were more likely to have received public funds from Head Start and public Pre-K and less likely to receive funds from private tuition compared to those in low-Hispanic-serving centers (Figure 5).

Most differences in ECE workforce characteristics between high- and low-Hispanic- serving settings observed in 2012 remained in 2019

The 2012 NSECE study provided the first representative portrait of the early childhood workforce across the full range of care settings used by families in the United States. Using the same design and similar surveys, the 2019 NSECE offers an updated profile of teachers and caregivers in the field during that year. Given the survey’s cross-sectional design, comparisons across these two point-in-time snapshots may reflect a combination of factors. Any differences in teacher/caregiver characteristics between the two time points may reflect changes occurring at the workforce level (e.g., teacher gains in education or training) and/or changes in the composition of the workforce as people leave and enter the field. Notably, the NSECE study team has reported that the number of individuals providing home-based early care and education was roughly 25 percent lower in 2019 than in 2012.5

With these caveats in mind, we compared our 2019 results with similar analyses using the 2012 NSECE data.e, 2, 6We found that the share of center- and home-based teachers and caregivers in high-Hispanic-serving settings (1 in 5) was the same in 2019 as it was in 2012. Other notable similarities and differences include the following (full results reported in Table 2):

- Most differences in ECE workforce characteristics between high- and low-Hispanic-serving settings observed in 2012 remained in 2019. At both times, high-Hispanic-serving teachers and caregivers were more likely than their low-Hispanic-serving counterparts to 1) provide greater representation of Hispanic ethnicity, languages spoken other than English, and immigrant experiences; 2) have an early childhood certificate or credential; and 3) experience mentored professional development activities.

- Overall, the percentage of early childhood teachers and caregivers with a four-year degree remained low in 2019. Notably, among the high-Hispanic-serving center-based workforce, the share with a four-year degree was smaller in 2019 (1 in 4) than in 2012 (1 in 3), while the share was larger in 2019 (1 in 3) than in 2012 (1 in 5) for unlisted home providers with low Hispanic enrollment.

- The prevalence of certain professional development (PD) experiences among ECE professionals also differed from 2012 to 2019. A smaller percentage of the workforce in both high- and low-Hispanic-serving ECE centers and homes attended PD workshops in 2019 than in 2012, although a larger percentage of those in high-Hispanic-serving centers received coaching or mentoring in 2019 relative to 2012. This shift in prevalence of different types of PD activities from one-time trainings to more relationship-based and on-going professional development is consistent with best practice recommendations in the field.

Conclusion and Implications

The 2019 NSECE data provide a detailed profile of the U.S. ECE workforce just prior to the global COVID-19 pandemic.f According to these data, 1 in 5 early childhood teachers and caregivers worked in a setting with high Hispanic enrollment of 25 percent or above, similar to what was observed in analyzing the 2012 NSECE data.2 The descriptive analysis in this report has highlighted several ECE workforce characteristics with potential implications for children’s experiences and examined how these characteristics varied across settings with high and low enrollments of Hispanic children.

We found few differences in ECE workforce education and experience levels by program Hispanic enrollment. High-Hispanic-serving teachers and caregivers compared favorably, however, on indicators of capacity for culturally and linguistically responsive services and engagement in ongoing professional development, relative to their counterparts in low-Hispanic-serving settings. High-Hispanic-serving ECE professionals were also more likely to be Hispanic themselves, to speak a language other than English, and to have personal experience with immigration. This type of demographic representation has been shown to offer key benefits for Latino children—for example, in terms of more effective supports for dual language learners7 and partnering with Hispanic families.8 Teachers and caregivers in high-Hispanic-serving settings, and in centers in particular, also reported higher rates of ECE credentialling, receipt of coaching or mentoring, and having a formal professional development plan than their peers in low-Hispanic-serving settings—characteristics that may support high-quality teaching practices. This set of results may be partially explained by our finding that high-Hispanic-serving settings were more likely than low-Hispanic-serving settings to have received Head Start and state public preschool funds, which are often accompanied by education and training requirements and resources. In general, these relative strengths of the workforce in high-Hispanic-serving settings are similar to what was observed in 2012.9 While some indicators were weaker in 2019 than in 2012 (e.g., rates of ECE credential attainment and professional development workshop attendance), these may reflect shifts in the field that have prioritized two- and four-year teaching degrees and mentored professional development.

While center-based programs, especially those of high quality, have been shown to support Latino children’s success in school,10 home-based providers also play an important role in the ECE landscape for Hispanic families. Compared to center-based providers, these providers tend to offer more culturally and linguistically responsive care11 (as our demographic findings also suggest) and greater flexibility to meet the scheduling needs of low-income working parents.12 Emerging evidence suggests that home-based ECE—and especially less formal family, friend, and neighbor care—served as a critical support to many families during the pandemic.13,14 Our findings of relatively low levels of education, credentialing, and access to mentored professional development activities among home-based providers point to an opportunity to invest more intentionally in this important segment of the ECE workforce serving Latino families.

Although this report has emphasized the high-Hispanic-serving ECE workforce, our results indicate that teachers and caregivers in low-Hispanic-serving settings still serve a substantial number of Hispanic children cumulatively, especially in centers. More than half of the center-based early childhood workforce in the United States teaches in a program with some Hispanic enrollment but totaling less than 25 percent. In these settings, Hispanic children are less likely to have teachers and caregivers—and, by definition, peers—who share their racial, ethnic, and linguistic background. Investments aimed at strengthening and supporting the ECE workforce to better serve Latino children should include these lower-enrollment settings as well, which may have unique needs.

Finally, it is important to acknowledge the wide-reaching effects of the COVID-19 pandemic, which impacted families’ needs and preferences for child care and the capacity of ECE programs and providers to deliver services. As such, some or all of the workforce findings reported here may have shifted over the course of the pandemic. Recovery efforts in the ECE sector should seek to monitor and build upon the strengths of the workforce serving Latino children—a large, growing, and diverse segment of the U.S. child population.

Data and Methods

Data for this analysis come from the 2019 National Survey of Early Care and Education, a set of four interrelated, nationally representative surveys of: 1) households with children under age 13, 2) center-based ECE programs, 3) the center-based provider workforce, and 4) the home-based provider workforce. We drew specifically on public use data from the center- and home-based surveys to describe the center-based workforce (including lead teachers, assistants, and aides who work in community-based centers, as well as pre-kindergarten and Head Start); the listed, home-based workforce (including teachers/caregivers who provide care in home settings registered on publicly available lists as meeting state regulations); and the unlisted, home-based workforce (including teachers/caregivers who provide care for children under age 13, who are not their own children, on a regular basis for at least five hours per week; unlisted home providers are not registered on publicly available child care lists and often include family members, friends, and neighbors).

The analytic sample for this brief includes 3,836 center-based, 3,294 listed home-based, and 990 unlisted home-based teachers and caregivers who serve children from birth to age 5 (not yet in kindergarten) and for whom information on the proportion of Hispanic children served was available (Table 1). Notably, a significant share of the center-based (18%) and listed home-based workforce (21%) could not be included in the current analysis because of missing data on the key variable of percent Hispanic child enrollment. In most of these cases, providers reported serving at least one Hispanic child but did not provide a specific number and could therefore not be classified as high- or low-Hispanic-serving. Analyses comparing teachers and caregivers with and without percent Hispanic enrollment data available suggested no differences between these two groups on the characteristics reported in this brief, with the exception that teachers and caregivers missing Hispanic enrollment data and excluded from the primary analysis were more likely to have a bachelor’s degree.

We conducted descriptive analyses on select characteristics of the workforce (see Definitions below) by type of ECE setting and the proportion of Hispanic children enrolled. Mean workforce differences across high- and low-Hispanic-serving settings were tested within type of care; significant differences at the p=.05 level are noted. All analyses were conducted in STATA and were weighted to be nationally representative of center-based classroom teaching staff and home-based teachers/caregivers. The sample weights for listed and unlisted home-based providers vary substantially, so these two groups were analyzed separately.

Definitions

High-Hispanic-serving captures center- and home-based settings where 25 percent or more of the children served are Hispanic. Those with fewer than 25 percent Hispanic enrollment are considered low-Hispanic-serving. For this analysis, center-based teachers and caregivers are categorized by the percentage of Hispanic children enrolled in their program rather than in their individual classroom. Center directors reported Hispanic enrollment among children from birth to age 5 (not yet in kindergarten), while home-based providers reported Hispanic enrollment based on all children served, from birth to age 12.

Hispanic ethnicity indicates whether the individual teacher/caregiver reported that they are Hispanic.

Speaks language other than English is based on teacher/caregiver report of whether they speak any other languages than English.g

Foreign-born nativity status indicates whether the teacher/caregiver was born outside the United States.

Education level captures whether a teacher/caregiver’s highest level of completed education is a bachelor’s degree or higher.

Child Development Associate (CDA) or state child care certification captures whether the teacher/caregiver has a CDA and/or state certification to care for children younger than age 13.

Worked in field 5 years or less is based on teacher/caregiver report of their years of experience working with children younger than age 13.

Engagement in professional development captures several aspects of workforce engagement in professional development. Center- and home-based teachers/caregivers reported on whether they had attended a workshop, received coaching or mentoring, or reviewed a professional development plan with a supervisor or mentor in the past 12 months.

Program sponsor type captures whether a center-based provider reports receiving Head Start funding, public Pre-K funds, CCDF child care subsidies, and/or parent tuitions or fees. These categories are not mutually exclusive.

[1] Additional items in the 2019 center workforce and home-based provider questionnaires asked about specific languages used during interactions with children and families. We decided to use the more general language question because the more specific variables are not available for home-based providers in the public use NSECE 2019 datafiles and, for the center-based workforce, collapsed response options make it difficult to identify Spanish-speaking center-based teachers (e.g., “Two or more languages: English and another language”).

Footnotes

a We use “Hispanic” and Latino interchangeably throughout this report. The terms are used to reflect the U.S. Census definition to include individuals having origins in Mexico, Puerto Rico, and Cuba, as well as other “Hispanic, Latino or Spanish” origins.

b We use the terms teachers and caregivers interchangeably in this profile of the ECE workforce to describe personnel who serve young children by providing educational opportunities and caregiving within a variety of center- and home-based settings.

c We use 25 percent as the cutoff for defining “high-Hispanic-serving” because 25 percent of children in the United States today are Hispanic;4 a higher cutoff would exclude providers in communities with lower densities of Hispanic families.

d Listed home-based providers appear on public child care registries and tend to enroll children with whom they have no prior relationship. Unlisted home-based providers include family members, friends, and neighbors, and typically care for children with whom they have a prior relationship.

e Published reports on the 2012 NSECE workforce in high- and low-Hispanic-serving settings conducted parallel analyses to those reported here but limited the analysis to teachers identifying as Hispanic, non-Hispanic Black, or non-Hispanic White. To appropriately test 2019-2012 differences, we replicated the 2012 NSECE analyses with a slightly larger sample of ECE teachers/caregivers inclusive of any racial/ethnic background to match our primary 2019 analysis sample.

f To assess the impact of the pandemic on the ECE landscape, the NSECE fielded a COVID-19 supplemental follow-up survey in 2020 and 2021 with center- and home-based providers included in the original 2019 NSECE sample.

g Additional items in the 2019 center workforce and home-based provider questionnaires asked about specific languages used during interactions with children and families. We decided to use the more general language question because the more specific variables are not available for home-based providers in the public use NSECE 2019 datafiles and, for the center-based workforce, collapsed response options make it difficult to identify Spanish-speaking center-based teachers (e.g., “Two or more languages: English and another language”).

Suggested Citation

Crosby, D., Mendez, J., & Stephens, C. (2023). Characteristics of the early childhood workforce serving Latino children. National Research Center on Hispanic Children & Families. https://doi.org/10.59377/564i2785e

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to thank the Steering Committee of the National Research Center on Hispanic Children & Families—along with Katherine Paschall, Kristen Harper, and Laura Ramirez—for their helpful comments, edits, and research assistance at multiple stages of this project. The Center’s Steering Committee is made up of the Center investigators—Drs. Natasha Cabrera (University of Maryland, Co-I), Danielle Crosby (University of North Carolina, Greensboro, Co-I), Lisa Gennetian (Duke University; Co-I), Lina Guzman (Child Trends and PI), Julie Mendez (University of North Carolina, Greensboro, Co-I), and Maria Ramos-Olazagasti (Child Trends and Building Capacity lead)—and federal project officers Drs. Ann Rivera, Jenessa Malin, and Mina Addo (Office of Planning, Research and Evaluation).

Editor: Brent Franklin

Designers: Catherine Nichols, Joseph Boven, and Sara Appel

About the Authors

Danielle Crosby, PhD, is a co-investigator of the National Research Center on Hispanic Children & Families, co-leading the research area on early care and education. She is an associate professor in the Department of Human Development and Family Studies at the University of North Carolina at Greensboro. Her research focuses on understanding how policies and systems shape early education access and quality for young children in low-income families.

Julia Mendez, PhD, is a co-investigator of the National Research Center on Hispanic Children & Families, co-leading the research area on early care and education. She is a professor in the Department of Psychology at the University of North Carolina at Greensboro. Her research focuses on risk and resilience among ethnically diverse children and families, with an emphasis on parent-child interactions and parent engagement in early care and education programs.

Christina Stephens, M.S., is a predoctoral fellow of the National Research Center on Hispanic Children & Families, in the research area on early care and education. She is a doctoral candidate in the Department of Human Development and Family Studies at the University of North Carolina at Greensboro. Her research focuses on understanding the factors and policies that promote child care access and quality, particularly among low-income families with young children.

About the Center

The National Research Center on Hispanic Children & Families (Center) is a hub of research to help programs and policy better serve low-income Hispanics across three priority areas: poverty reduction and economic self-sufficiency, healthy marriage and responsible fatherhood, and early care and education. The Center is led by Child Trends, in partnership with Duke University, University of North Carolina at Greensboro, and University of Maryland, College Park. The Center is supported by grant #90PH0028 from the Office of Planning, Research, and Evaluation within the Administration for Children and Families in the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services.

The National Research Center on Hispanic Children & Families is solely responsible for the contents of this brief, which do not necessarily represent the official views of the Office of Planning, Research, and Evaluation, the Administration for Children and Families, or the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services.

Copyright 2023 by the National Research Center on Hispanic Children & Families.

References

1 Mendez Smith, J., Crosby, D., & Stephens, C. (2021). Equitable access to high-quality early care and education: opportunities to better serve young Hispanic children and their families. In L. Gennetian & M. Tienda (Eds.): Investing in Latino Youth. Annals of the American Academy of Political and Social Science (AAPSS), 696(1), 80–105. Sage. https://doi.org/10.1177/00027162211041942

2 Guzman, L., Hickman, S., Turner, K. & Gennetian, L. (2018). Who is caring for Latino children: The characteristics of early care and education teachers and caregivers serving a high proportion of Hispanic children. National Research Center on Hispanic Children and Families. https://www.hispanicresearchcenter.org/research-resources/who-is-caring-for-latino-children-the-characteristics-of-the-early-care-and-education-teachers-and-caregivers-serving-a-high-proportion-of-hispanic-children/

3 NSECE Project Team (National Opinion Research Center). (2021). National Survey of Early Care and Education (NSECE), [United States], 2019. Inter-university Consortium for Political and Social Research [distributor]. https://doi.org/10.3886/ICPSR37941.v3

4 Child Trends. (2018). Racial and Ethnic Composition of the Child Population. Retrieved from https://www.childtrends.org/indicators/racial-and-ethnic-composition-of-the-child-population.

5 Datta, A. R., Milesi, C., Srivastava, S., Zapata-Gietl, C. (2021). NSECE Chartbook – Home-based Early Care and Education Providers in 2012 and 2019: Counts and Characteristics. OPRE Report #2021-85. Office of Planning, Research and Evaluation, Administration for Children and Families, U.S. Department of Health and Human Services. https://www.acf.hhs.gov/opre/report/home-based-early-care-and-education-providers-2012-and-2019-counts-and-characteristics

6 Mendez, J., Crosby, D., Guzman, L. & Lopez, M. (2017). Centers serving high percentages of young Hispanic children compare favorably to other centers on key predictors of quality. National Research Center on Hispanic Children & Families. https://www.hispanicresearchcenter.org/research-resources/centers-serving-high-percentages-of-young-hispanic-children-compare-favorably-to-other-centers-on-key-predictors-of-quality/

7 Downer, J., Goble, P., Myers, S. & Pianta, R.C. (2016). Teacher-child race/ethnicity match within pre-kindergarten classrooms and children’s early school adjustment. Early Childhood Research Quarterly, 37, 26-38. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ecresq.2016.02.007

8 Markowitz, A. J., Bassok, D., & Grissom, J. A. (2020). Teacher-child racial/ethnic match and parental engagement with Head Start. American Educational Research Journal, 57(5), 2132–2174. https://doi.org/10.3102/0002831219899356

9 Guzman, L., Hickman, S., Turner, K. & Gennetian, L. (2018). Who is caring for Latino children: The characteristics of early care and education teachers and caregivers serving a high proportion of Hispanic children. National Research Center on Hispanic Children and Families. https://www.hispanicresearchcenter.org/research-resources/who-is-caring-for-latino-children-the-characteristics-of-the-early-care-and-education-teachers-and-caregivers-serving-a-high-proportion-of-hispanic-children/

10 Ansari, A., Lόpez, M., Manfra, L., Bleiker, C., Dinehart, L. H., Hartman, S. C., & Winsler, A. (2016). Differential third-grade outcomes associated with attending publicly funded preschool programs for low-income Latino children. Child Development, 88(5), 1743–1756. https://doi.org/10.1111/cdev.12663

11 Paschall, K., Madill, R., & Halle, T. (2020). Demographic characteristics of the early care and education workforce: Comparisons with child and community characteristics. OPRE Report #2020-108. Office of Planning, Research, and Evaluation, Administration for Children and Families, U.S. Department of Health and Human Services. https://www.acf.hhs.gov/sites/default/files/documents/opre/demographic-characteristics-ECE-dec-2020.pdf

12 Crosby, D., Mendez, J., Guzman, L., López, M. (2016). Hispanic Children’s Participation in Early Care and Education: Type of Care by Household Nativity Status, Race/Ethnicity, and Child Age. National Research Center on Hispanic Children and Families. https://www.hispanicresearchcenter.org/research-resources/hispanic-childrens-participation-in-early-care-and-education-type-of-care-by-household-nativity-status-race-ethnicity-and-child-age/

13 Home Grown Child Care (2020). Family, Friend, and Neighbor Caregivers during COVID-19: Preliminary Data from Home Grown Emergency Fund Communities. https://homegrownchildcare.org/wp-content/uploads/2020/10/HomeGrown_FamilyFriendNeighbor.pdf

14 Porter, T., Bromer, J., Melvin, S., Ragonese-Barnes, M., & Molloy, P. (2020). Family child care providers: Unsung heroes in the Covid-19 crisis. Chicago, IL: Herr Research Center, Erikson Institute. https://www.erikson.edu/wp-content/uploads/2020/09/Family-Child-Care-Providers_Unsung-Heroes-in-the-COVID-19-Crisis.pdf