Feb 8, 2023

Research Publication

Local Agency Staff in North Carolina’s Child Care Subsidy Program Offer Perspectives on Engaging Hispanic Families During COVID-19

Authors:

Introduction

The COVID-19 pandemic has significantly disrupted the lives of Hispanicb children and families in the United States. Hispanic families have been disproportionately burdened by COVID-19 infection, hospitalization, and mortality,1 and have experienced major economic impacts such as job losses and decreases in family income.2,3 Latino families have also experienced high rates of food insufficiency4 and reported heightened concerns about housing security due to the pandemic.5 Data also show that the rate of Latino child poverty increased early during the pandemic.6

COVID-19 has impacted the child care sector substantially, with large-scale closures across the United States,7 and Hispanic families were hit particularly hard. Historically, Latino families have had less access to paid leave8 and, during the pandemic, were more likely to leave a job due to child care disruptions and less likely to use paid leave to care for their children than their White counterparts.9 These findings raise concerns about how low-income Hispanic families are navigating the compounding stressors of lack of care and economic instability.

About this brief

This brief is part of a series to examine state-level policies that shape access to social service and safety net programs, and the ways in which state and federal policy implementation at the local level may affect the reach of program benefits among Latino families. The briefs in this series focus on one or more of the 13 statesa in which Latino children make up a large proportion of all children. To date, related research applying a Latino lens to examine state-level policy and practice prior to the pandemic is available for the Child Care and Development Fund (CCDF) child care subsidy program (see here and here) and Temporary Assistance to Needy Families (TANF) income assistance programs (see here, here, and here), across and within multiple state contexts. In this brief, we examine adaptations made by North Carolina’s child care subsidy program during the pandemic and how they may have affected Latino families’ access.

Subsidized child care expands access to care, thereby serving as an important safety net for low-income children and families in the United States. The largest federally funded child care subsidy program is the Child Care and Development Fund (CCDF), which is administered with considerable latitude by individual states. CCDF-funded child care subsidy programs scrambled to respond to families’ changing needs during the pandemic, but some aspects of the response have been less clear: the ways in which local subsidy programs adapted, the extent to which programs met the unique needs of Hispanic families, and the opportunities and challenges in serving Latino families that emerged in response to the pandemic.

This brief draws from a survey of local child care subsidy staff in North Carolina in Spring 2021 to explore their perspectives about engaging Hispanic families during the COVID-19 pandemic. North Carolina has a growing Hispanic population and provides a unique view of how state subsidy offices adapted to meet families’ needs. First, we summarize our key findings and our recommendations for other subsidy staff serving Hispanic families. Next, we explore how general child care subsidy service provision changed during the pandemic, and then examine how these changes impacted the ways in which subsidy staff provided services to Hispanic families in particular. Then, we share more detailed staff recommendations to improve Hispanic families’ access to and use of child care subsidies. Through much of this brief, we use direct quotes to highlight the voices of local subsidy staff, including both frontline workers and administrators. Finally, we explore how staff viewpoints may differ based on their demographic and employment characteristics. These findings can inform efforts in North Carolina and other states to increase engagement with Hispanic families.

The following sections highlight findings from the survey of subsidy staff, conducted from April to June 2021. A total of 189 subsidy workers in 83 (out of 100) counties across North Carolina participated in the survey. Approximately two thirds of survey respondents were frontline caseworkers (n=118) and one third were administrators or supervisors (n=71).

Key Findings

The COVID-19 pandemic disrupted business as usual for most subsidy offices and many responded in creative ways to continue to reach families:

- Most subsidy offices made significant changes to how child care subsidies were provided, particularly by allowing families to apply electronically so that they did not need to physically visit offices.

- Some subsidy offices also relaxed verification and recertification requirements for families for periods during the pandemic, which staff reported improved families’ access to child care.

- Some staff reported a decrease in the waiting lists for child care slots, prompting more community outreach.

Subsidy staff also shared how these changes specifically impacted Hispanic families, including both challenges and potential benefits:

- Some staff reported that Hispanic families sometimes had difficulty with electronic communication due to technology or language barriers, and that many preferred to come into offices and meet with caseworkers face to face. However, offices were typically closed temporarily during periods of the pandemic.

- Some staff also reported benefits for Hispanic families, including increased communication between families and child care subsidy offices and families’ ability to get off of waiting lists and transfer to preferred child care programs because of open slots.

- Because of overall lower enrollment during the pandemic, some subsidy staff reported that their offices increased outreach to Hispanic families.

Summary of recommendations for subsidy program staff

Subsidy staff shared several general recommendations for improving child care subsidy access for Hispanic families:

- Expand community outreach by providing information about available services and eligibility requirements and partnering with organizations that are trusted within the Hispanic community.

- Increase Spanish-speaking staff—especially the number of child care subsidy staff, agency interpreters, and child care providers in the community.

- Provide materials in Spanish for every subsidy office, including application and recertification forms and information sheets.

- Increase subsidy funding and culturally responsive child care capacity so that more Hispanic and Latino families can be served within the system.

- Address immigration concerns for Hispanic families, including uncertainty about whether immigration status impacts eligibility and concerns for safety within subsidy offices.

- Make application processes and eligibility requirements adopted during the pandemic permanent to continue to facilitate subsidy use among Hispanic families. Changes that should be made permanent include parent fee waivers and relaxed verification and recertification requirements.

- Provide more training to staff around cultural awareness and diversity, Spanish language skills, addressing immigration status with families, and general subsidy program policies and procedures.

Pandemic Changes to Child Care Subsidy Processes and Service Provision, for All Families

Local subsidy staff in North Carolina responded to a series of closed and open-ended questions about changes made due to the pandemic in providing services to all families. This section describes their responses.

Overall, 33 percent of administrators (n=66) reported that their subsidy office had physically closed at some point during the pandemic. At the time of the survey, 60 percent of administrators (n=65) reported that families were currently coming into the office in person. In response to open-ended questions, most subsidy staff (both caseworkers and administrators) reported some change in local service provision due to COVID-19, and 19 percent reported no changes.

Changes in how families apply for child care subsidies

In response to open-ended questions, a majority of local subsidy staff (59%, 80/135) reported that families applied for child care subsidies in new and different ways as a result of the COVID-19 pandemic. Subsidy staff reported that it was much easier for families to apply and that, in many cases, families were able to submit applications electronically, by fax, using their phone, and/or by submitting applications by mail or physically dropping them off at the office. Overall, 7 percent of staff who reported changes shared that some in-person access was also maintained during the pandemic. Some subsidy staff reported positive feedback from families about these changes.

We conduct phone interviews rather than face to face. We conduct feedback emails to our clients to ensure they are getting an overall good experience … So far, the feedback from clients has been: “This process was quick and simple,” “I saved time because I did not have to schedule an appointment,” “I was able to apply on my lunch break without taking time off work.” – Frontline worker

Some agencies were very creative and met clients at parks, restaurants, in the parking lot, etc. A few subsidy staff also shared that they were able to communicate and facilitate the subsidy process by working with child care providers:

We do applications by email, phone, or fax. Clients fax, leave in a drop box outside agency, or email evidence of eligibility and recertifications. We get parent signatures by faxing or emailing documents to day care providers for parents to sign when they pick up or drop off kids. – Frontline worker

We do applications by email, phone, or fax. Clients fax, leave in a drop box outside agency, or email evidence of eligibility and recertifications. We get parent signatures by faxing or emailing documents to day care providers for parents to sign when they pick up or drop off kids. – Frontline worker

Other changes in service provision

Respondents also reported other changes in service provision as a result of the pandemic. Overall, 10 percent of staff who described changes in service delivery reported that verification and recertification requirements were relaxed; for example, in some cases, recertifications were waived for up to 12 months. Additionally, a few respondents reported that families benefited from fee reductions or waivers.c Some respondents also noted differences in how clients were referred to the child care subsidy office, since child protective services workers were no longer conducting home visits. Some county offices also experienced a decrease in their waiting lists for child care slots, prompting more outreach; in some cases, staff utilized social media and newspaper ads to reach families.

Changes in communication with families

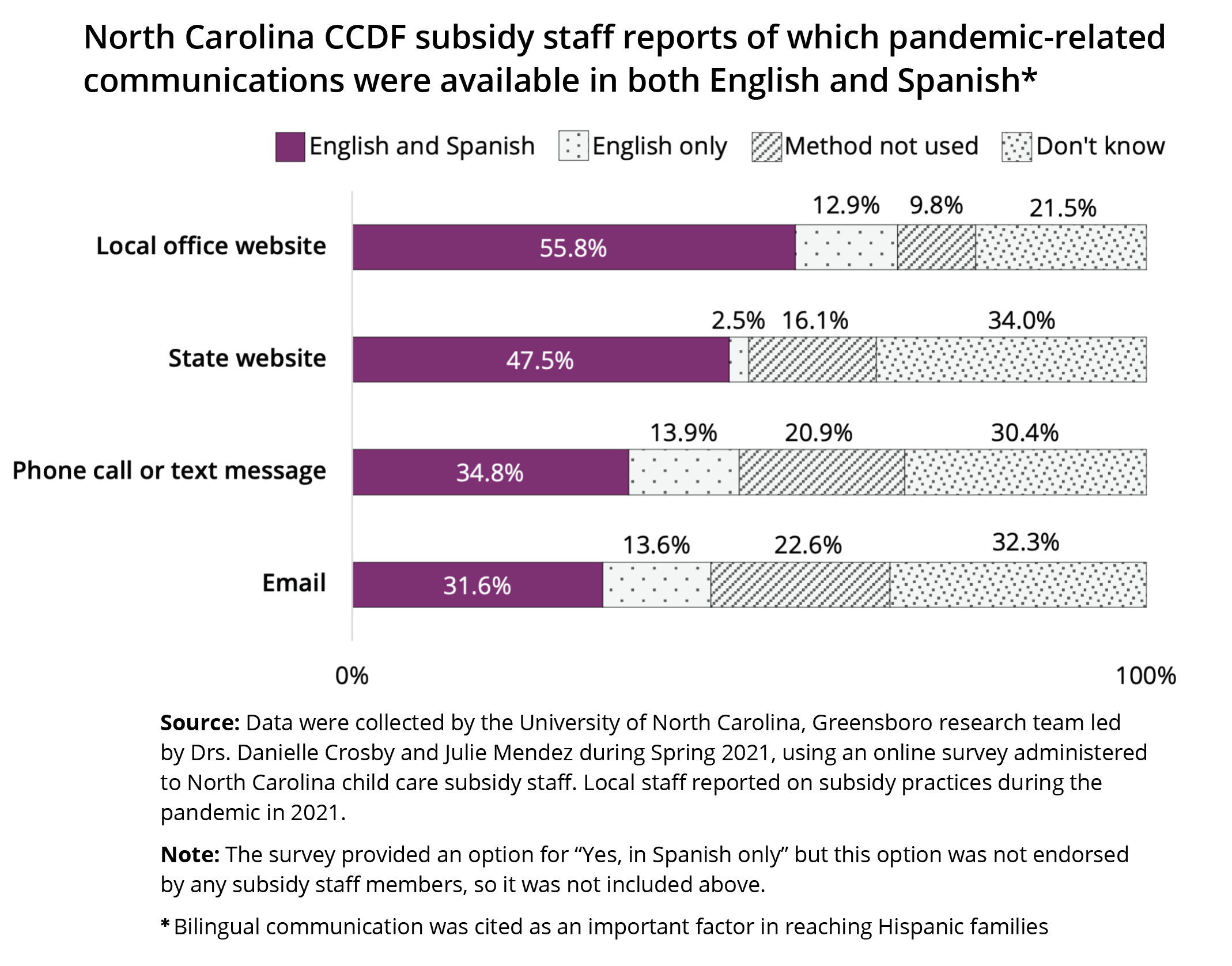

Local subsidy staff reported on how their agencies communicated changes to families, and whether these changes were communicated in both English and Spanish. Many staff did not know whether materials were available in Spanish, and—in some cases—materials were only available in English (see Figure 1).

Impacts of Child Care Subsidy Adaptations for Hispanic Families

In addition to asking about changes in the subsidy application process and/or provision of services due to the COVID-19 pandemic, the survey also asked local agency staff whether they thought that any of the changes had been especially impactful for Hispanic families. Overall, 59 percent of local subsidy staff (60/101) reported “no” or n/a when asked, in an open-ended question, whether any changes in service provision had impacted Hispanic families in particular. Another 9 percent reported that changes had similarly impacted both Hispanic and non-Hispanic families. Staff from high- and low-Hispanic-density counties responded in similar ways to this question (i.e., those either above or below the average North Carolina county’s density of Hispanic children in 2020, which was 15.3%; see also the methodology section).

Another 13 percent of staff identified negative impacts for Hispanic families, particularly when in-person services were paused due to COVID-related social distancing measures. These subsidy staff shared that Latino families experienced language barriers, difficulties accessing the internet or other electronic communication channels, and difficulties accessing in-person services (which some Latino families preferred). A few subsidy staff also noted decreases in referrals or, in some cases, difficulties finding open child care slots for Hispanic families. Examining variation across respondents, most who identified negative impacts for Hispanic families identified as Hispanic themselves, as having advanced Spanish language skills, and as having less than six years of experience. In other words, subsidy staff who identified as Hispanic appear to be more aware of how changes in service provision might have impacted the Hispanic population.

Barriers in accessing subsidized child care

Subsidy staff indicated that their capacity to communicate in Spanish operated as either a barrier or facilitator to serving Latino families:

I think most Hispanic-speaking families don’t call due to the language barrier that we have in the agency. – Administrator

I think more needs to be done for the Hispanic population. We only have three interpreters for the whole agency when needing assistance for Hispanic population. – Frontline worker

I believe the main issue with our Hispanic families is and has been the inability to communicate and understand the process… I’ve only worked in this department for six months, but I can say that it has been beneficial to those families now that they have myself who can translate documents and answer questions. – Frontline worker

I believe the main issue with our Hispanic families is and has been the inability to communicate and understand the process… I’ve only worked in this department for six months, but I can say that it has been beneficial to those families now that they have myself who can translate documents and answer questions. – Frontline worker

While subsidy staff reported that electronic communication had eased the subsidy process for some families, they underscored that other families preferred in-person services:

Electronically signing paperwork can be hard for clients depending on the technology that they have available to them. For example, if they don’t have access to a computer or a printer at home, that can make things difficult. And then to try to do all this with a language barrier must be frustrating and exhausting. – Frontline worker

I would say in general, the move to mostly electronic correspondence probably has had negative impacts, especially for those who may not be literate and perceive filling out online communication challenging. – Administrator

The [Hispanic] population likes to hand deliver forms and verifications and will often not mail in or email as they prefer face-to-face contact. This has hindered some families. – Administrator

Improvements in access to subsidized child care

Local subsidy staff were also asked whether families’ access to subsidized child care services had improved in any way in the context of changes to service provision made in response to the pandemic. Again, many respondents (41%) noted that both Hispanic and non-Hispanic families were able to take advantage of the newer, faster application processes, including applying electronically.

Other staff members mentioned that fee waivers and increased fundingb had helped Hispanic families (13% of respondents), as had the relaxation of verification and recertification requirements (6% of respondents) during the pandemic.

Parent fees have been waived for several months during the pandemic, which is helpful not only for those parents struggling with income but those that still have income and are struggling. – Frontline worker

Parents have had their parent fees paid by the State. The 90-day job searches have been extended. Some parents have been on a 90-day job search for the past year. – Administrator

Some subsidy staff noted seeing an increase in interest for subsidies from Hispanic families, that families improved their knowledge of technology, and that overall communication between families and agencies improved, allowing agencies to better meet Hispanic families’ needs. Additionally, although overall demand for—and enrollment in—child care may have decreased during the pandemic, such decreases inadvertently allowed some Hispanic families to move off the waitlist for care or change to a preferred program.

Before the pandemic, all child care slots were filled. Now, there are openings at all facilities, including the very best-quality programs. Families can transfer to child care however they want to. – Frontline worker

Lastly, because of lower enrollments, some subsidy offices increased their outreach to Hispanic families to better reach this population.

We have placed ads in the newspaper in both English and Spanish, we have placed applications on the website in English and Spanish. We have had our Hispanic Interpreter reach out to families to start the application process by phone. – Administrator

Staff Recommendations for Other Subsidy Offices

In response to open-ended questions, local subsidy staff offered several strategies to improve Hispanic families’ access to and utilization of child care subsidies.

Increase community outreach. Several respondents did not believe that Hispanic families knew about child care subsidies and felt that many were unaware of their eligibility. One frontline worker shared that they “rarely receive Hispanic applicants … unsure if it is lack of knowledge on the program or just disinterest in the services.” An administrator also recommended “more networking and outreach through organizations that are trusted within the Hispanic community.”

Increase Spanish-speaking staff. Many subsidy staff mentioned that there were not enough Spanish-speaking staff to reach Hispanic families and called for additional Spanish-speaking child care providers, subsidy staff, and agency interpreters. One administrator explained, “We need to help [to] facilitate increased child care licensure amongst native Spanish speakers (we have no home child care providers who speak Spanish, for example in our county, despite the population).” A frontline worker stated, “The local DSS [Department of Social Services] can recruit more interpreters to assist with programs. It will make no sense to recruit the Hispanic population to apply for services if the workers are not knowledgeable and can communicate properly with them.”

Provide materials in Spanish. Similarly, subsidy staff explained that many materials were not available in Spanish—a potentially helpful accommodation for families. One frontline worker reflected, “[We need] more forms, publications in Spanish. At recertification, if a Spanish-speaking family receives the English recert[ification] form, they may not know what it is or what to do with it.” An administrator recommended providing “state-generated forms in Spanish. All forms should be in Spanish and not left up to counties to translate.”

Increase subsidy funding and culturally responsive child care capacity. Several subsidy staff mentioned that increasing subsidy funding would allow more children and families to be served, which would benefit both Hispanic and non-Hispanic families. A frontline worker explained, “Our request is for more subsidy funding so we could help our working families on the waiting list who are working and request Subsidized Child Care Services while they work. These families are currently having to pay private pay, which makes it very difficult for these families.” Subsidy staff also noted that it would be helpful to hire more staff in their agencies, in general, and to add child care slots to serve families—particularly families with infants and toddlers.

Address families’ concerns regarding immigration status. Several subsidy staff recommended taking additional steps to ensure that Hispanic families feel safe when applying for subsidies. For example, one frontline worker reflected, “It needs to be clearer for Hispanic families to understand whether they need citizenship status to apply for subsidy … There needs to be clear information out there about what documents DSS [Department of Social Services] is going to ask for … and how DSS is going to use information about the household members that are required to be reported … The information should be available before someone ‘comes in’ to apply so that they can inform themselves and feel empowered.” An administrator recommended implementing “policies on immigration that do not allow ICE or police to come into facilities looking for parents. We already maintain a level of confidentiality that does not allow us to give this information to anyone. We need a second layer to make sure ICE or police do not have access to information about our Hispanic families.”

Make pandemic-instituted application processes and eligibility requirements permanent. Several subsidy staff recommended making changes to how families apply and qualify for services. For example, some staff noted that parent fee waivers, relaxed verification and recertification requirements, and electronic application processes should be continued after the pandemic. Others recommended increasing eligibility income limits so that more families could qualify for child care subsidies.

Provide training to staff. Several subsidy staff suggested providing training for child care subsidy staff, including on the topics of cultural awareness and diversity, Spanish language skills, addressing immigration status, and general subsidy program policies and procedures. One frontline worker recommended “training on the dynamics of the Hispanic households and information on immigration laws as they relate to application for services.” In terms of Spanish language training, another frontline worker explained, “If the state would provide Spanish speaking classes as continuing education for those who have a desire to learn Spanish (like myself), this would be an incredible experience … To see the State of North Carolina bring this in as a ‘continuing education’ program would make a huge positive impact on the Hispanic families that we serve. We would not have to succumb[ed] to using the (expensive) language [translation] line. We could develop a deeper level of communication with our Hispanic clients through speaking their language.”

Conclusion

The COVID-19 pandemic caused significant changes in the lives of Hispanic children and families and to the public benefit systems that serve them. The child care sector, in particular, experienced marked instability and widespread child care closures that have disproportionately impacted Hispanic families.8 North Carolina, as a state with a growing Hispanic population,10 can offer a unique view into how local child care subsidy staff engaged Hispanic families during the pandemic. The surveyed subsidy staff shared several changes that were made to child care subsidy provision due to the pandemic (like the use of electronic communication), but not all change were positive: Some Hispanic families experienced new language and technological barriers when trying to access services via new methods. Other staff noted opportunities that emerged in response to the pandemic, including the lack of a wait list; this, in turn, opened up staff time to do greater outreach in Latino communities. Another opportunity was the loosening of documentation requirements that may have improved access for Latino families. Staff also shared several concrete recommendations to improve engagement with Hispanic families, including increasing community outreach, providing more training to staff, addressing immigration concerns, and ensuring that materials and services are provided in Spanish.

Methodology

Subsidy staff survey and sample

The North Carolina child care subsidy survey used for this brief is part of a larger multi-method study capturing stakeholder perspectives on child care subsidy implementation and implications for Hispanic families’ access and utilization of the CCDF program. An online survey with closed and open-ended questions was conducted with 189 county-level CCDF subsidy workers in North Carolina in 2021. Subsidy workers in 83 (out of 100) counties across North Carolina participated in the survey. Approximately two thirds of survey respondents were frontline staff (n=118) and one third were administrators or supervisors (n=71). More than half of the subsidy workers (51%) had extensive work experience (i.e., 7 years or more) at their agencies and about 5 percent self-identified as native or fluent Spanish speakers—with 4 percent identifying as Hispanic or Latinx. This brief analyzed a subset of closed and open-ended questions related to the impacts of COVID-19 on the provision of child care subsidies, and the impacts of changes for Hispanic families in particular and recommendations for better supporting subsidy access for Hispanic families. A total of 181 subsidy staff responded to at least one open-ended survey question; the percentage who responded to each open-ended question varied, from 33 percent to 71 percent.

Analysis

Qualitative thematic coding was utilized for open-ended responses to capture nuance and explore patterns across respondents. A team of two coders coded open-ended survey response questions and used Dedoose, a cloud-based QDA software, for analysis. Coders reached 80 percent agreement before they began independent coding. Analytic memos were used throughout coding to identify material relevant to other survey questions, coding questions, new code ideas, helpful context, etc. and then reviewed by the team. New codes and subcodes were then added as appropriate. The relationship between qualitative codes and demographic and environmental characteristics were also analyzed to assess for potential patterns in qualitative results. Specifically, differences were examined by respondent role (frontline worker or administrator), years of experience (0-6 years or 7+ years), Hispanic ethnicity (yes or no), Spanish fluency (minimal skills or advanced skills), and county-level Hispanic density for children under age 10 (below or above the average North Carolina county’s density of Hispanic children in 2020, which was 15.3%).

Footnotes

a The 13 states are Arizona, California, Colorado, Florida, Georgia, Illinois, New Jersey, New York, New Mexico, North Carolina, Pennsylvania, Texas, and Washington.

b We use “Hispanic,” “Latino,” and “Latinx” interchangeably throughout this brief. Consistent with the U.S. Census Bureau’s definition, this includes individuals having origins in Mexico, Puerto Rico, Cuba, as well as other “Hispanic, Latino or Spanish” origins.

c With funding from the federal CARES Act and via repurposed state dollars, the Department of Health and Human Services, Division of Child Development and Early Education covered parental copayments periodically during the pandemic, meaning that providers did not collect copayments from families and, instead, the state lead agency included these costs in subsidy payments to providers. In North Carolina, most parents receiving subsidized child care must pay 10 percent of their gross monthly income as the copay (which is above the federal guidance for affordable care of 7% or less of income).

Suggested Citation

Palmer Molina, A., Crosby, D., Mendez, J., Stephens, C., Gonzalez, R. (2023). Local agency staff in North Carolina’s Child Care Subsidy Program offer perspectives on engaging Hispanic families during COVID-19. National Research Center on Hispanic Children & Families. https://doi.org/10.59377/707b5266y

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to thank the Steering Committee of the National Research Center on Hispanic Children & Families—along with Dr. Julia Henly, Kristen Harper, and Laura Ramirez—for their helpful comments, edits, and research assistance at multiple stages of this project. The Center’s Steering Committee is made up of the Center investigators—Drs. Natasha Cabrera (University of Maryland, Co-I), Danielle Crosby (University of North Carolina, Greensboro, Co-I), Lisa Gennetian (Duke University; Co-I), Lina Guzman (Child Trends and PI), Julie Mendez (University of North Carolina, Greensboro, Co-I), and Maria Ramos-Olazagasti (Child Trends and Building Capacity lead)—and federal project officers Drs. Ann Rivera, Jenessa Malin, and Mina Addo (Office of Planning, Research and Evaluation).

Editor: Brent Franklin

Designer: Catherine Nichols

About the Authors

Abigail Palmer Molina, PhD, LCSW, is a research scholar with the National Research Center on Hispanic Children & Families, in the research area on early care and education. She is an assistant professor in social work at Erikson Institute in Chicago, Illinois. Her research focuses on promoting maternal, child, and family well-being during the early childhood years, with an emphasis on implementing two-generation approaches in home visiting, children’s mental health systems, and early childhood education.

Danielle Crosby, PhD, is a co-investigator of the National Research Center on Hispanic Children & Families, co-leading the research area on early care and education. She is an associate professor in the Department of Human Development and Family Studies at the University of North Carolina at Greensboro. Her research focuses on understanding how policies and systems shape early education access and quality for young children in low-income families.

Julia Mendez, PhD, is a co-investigator of the National Research Center on Hispanic Children & Families, co-leading the research area on early care and education. She is a professor in the Department of Psychology at the University of North Carolina at Greensboro. Her research focuses on risk and resilience among ethnically diverse children and families, with an emphasis on parent-child interactions and parent engagement in early care and education programs.

Christina Stephens, MS, is a predoctoral fellow of the National Research Center on Hispanic Children & Families, in the research area on early care and education. She is a doctoral student in the Department of Human Development and Family Studies at the University of North Carolina at Greensboro. Her research focuses on understanding the factors and policies that promote child care access and quality, particularly among low-income families with young children.

Rosy Gonzalez, BS, received her bachelor’s degree in psychology from the University of North Carolina at Greensboro. She currently works with children with autism spectrum disorders and provides tailored programming to meet client needs. Her research background is in mental health and marginalized communities with a focus on Latinx families and their children.

About the Center

The National Research Center on Hispanic Children & Families (Center) is a hub of research to help programs and policy better serve low-income Hispanics across three priority areas: poverty reduction and economic self-sufficiency, healthy marriage and responsible fatherhood, and early care and education. The Center is led by Child Trends, in partnership with Duke University, University of North Carolina at Greensboro, and University of Maryland, College Park. The Center is supported by grant #90PH0028 from the Office of Planning, Research, and Evaluation within the Administration for Children and Families in the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services.

The National Research Center on Hispanic Children & Families is solely responsible for the contents of this brief, which do not necessarily represent the official views of the Office of Planning, Research, and Evaluation, the Administration for Children and Families, or the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services. Copyright 2023 by the National Research Center on Hispanic Children & Families.

References

1 Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. (2021). Risk for COVID-19 infection, hospitalization, and death by race/ethnicity. https://www.cdc.gov/coronavirus/2019-ncov/covid-data/investigations-discovery/hospitalization-death-by-race-ethnicity.html

2 Saenz, R. & Sparks, C. (2020). The inequities of job loss and recovery amid the COVID-19 pandemic. Durham, NH: Carsey School of Public Policy. https://carsey.unh.edu/publication/inequities-job-loss-recovery-amid-COVID-pandemic

3 Vargas, E. D., & Sanchez, G. R. (2020). COVID-19 is having a devastating impact on the economic well-being of Latino families. Journal of Economics, Race, and Policy, 3(4), 262–269. https://doi.org/10.1007/s41996-020-00071-0

4 Chen, Y. (2020). During COVID-19, 1 in 5 Latino and Black households with children are food insufficient. Bethesda, MD: National Research Center on Hispanic Children & Families. https://www.hispanicresearchcenter.org/research-resources/during-covid-19-1-in-5-latino-and-black-households-with-children-are-food-insufficient/

5 Chen, Y. & Guzman, L. (2021). 4 in 10 Latino and Black households with children lack confidence that they can make their next housing payment, one year into COVID-19. Bethesda, MD: National Research Center on Hispanic Children & Families. https://www.hispanicresearchcenter.org/research-resources/4-in-10-latino-and-black-households-with-children-lack-confidence-that-they-can-make-their-next-housing-payment-one-year-into-covid-19/

6 Chen, Y. & Thomson, D. (2021). Child poverty increased nationally during COVID, especially among Latino and Black children. Child Trends. https://www.childtrends.org/publications/child-poverty-increased-nationally-during-covid-especially-among-latino-and-black-children

7 Lee, E. K., & Parolin, Z. (2021). The care burden during COVID-19: A national database of child care closures in the United States. Socius, 7. https://doi.org/10.1177/23780231211032028

8 Bartel, A. P., Kim, S., Nam, J., Rossin-Slater, M., Ruhm, C., Waldfogel, J. (2019). Racial and ethnic disparities in access to and use of paid family and medical leave: evidence from four nationally representative datasets. Monthly Labor Review. U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics. https://doi.org/10.21916/mlr.2019.2

9 Chen, Y., Ferreira van Leer, K., & Guzman, L. (2021). Many Latino and Black households made costly work adjustments in spring 2021 to accommodate COVID-related child care disruptions. Bethesda, MD: National Research Center on Hispanic Children & Families. https://www.hispanicresearchcenter.org/research-resources/many-latino-and-black-households-made-costly-work-adjustments-in-spring-2021-to-accommodate-covid-related-child-care-disruptions/

10 Turner, K., Wildsmith, E., Guzman, L., & Alvira-Hammond, M. (2016). The Changing Geography of Hispanic Children and Families. Bethesda, MD: National Research Center on Hispanic Children & Families. https://www.hispanicresearchcenter.org/research-resources/the-changing-geography-of-hispanic-children-and-families/