Jun 6, 2023

Data Snapshot, Research Publication

Top Latino Metro Areas Saw Large Declines in Child Care Employment Early in the Pandemic, With Slow Recovery Among Latino Child Care Workers

Authors:

The COVID-19 pandemic negatively affected employment across many occupations. The child care industry and child care workers were particularly hard hit, experiencing employment losses at the onset of the pandemic that surpassed overall employment declines in the United States for workers in all other occupations combined. The child care sector has also rebounded more slowly than other employment fields. To examine how one aspect of the sector—specifically, child care workers in Hispanica communities—fared during the pandemic and the subsequent recovery, we build on a recently published national analysis of the child care workforce from the University of Michigan’s Poverty Solutions. We focus here on metropolitan areas with high densities of Hispanic populations—defined as metropolitan areas in which more than 20 percent of residents identify as Hispanic, the majority of which are located across six states.b

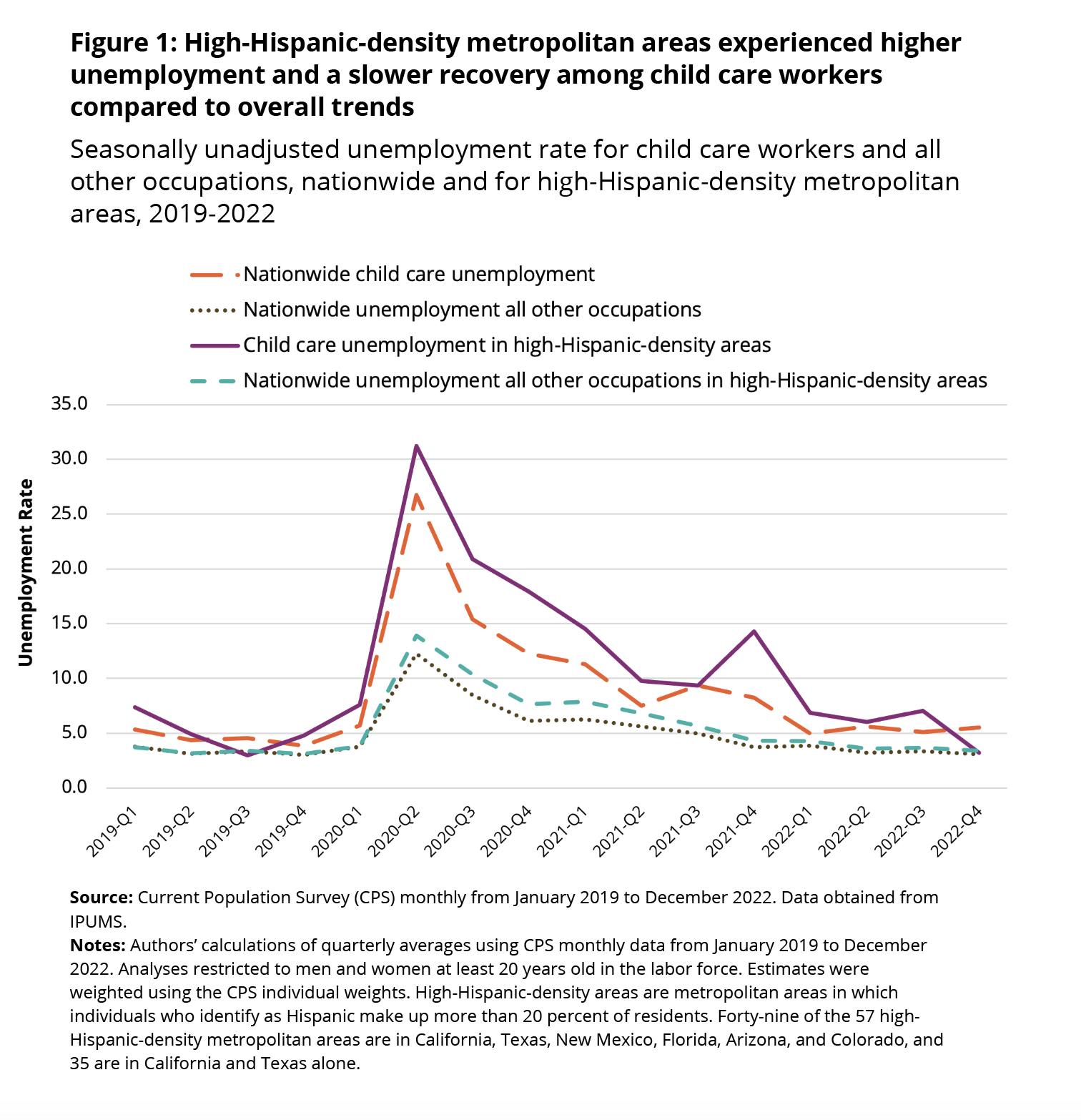

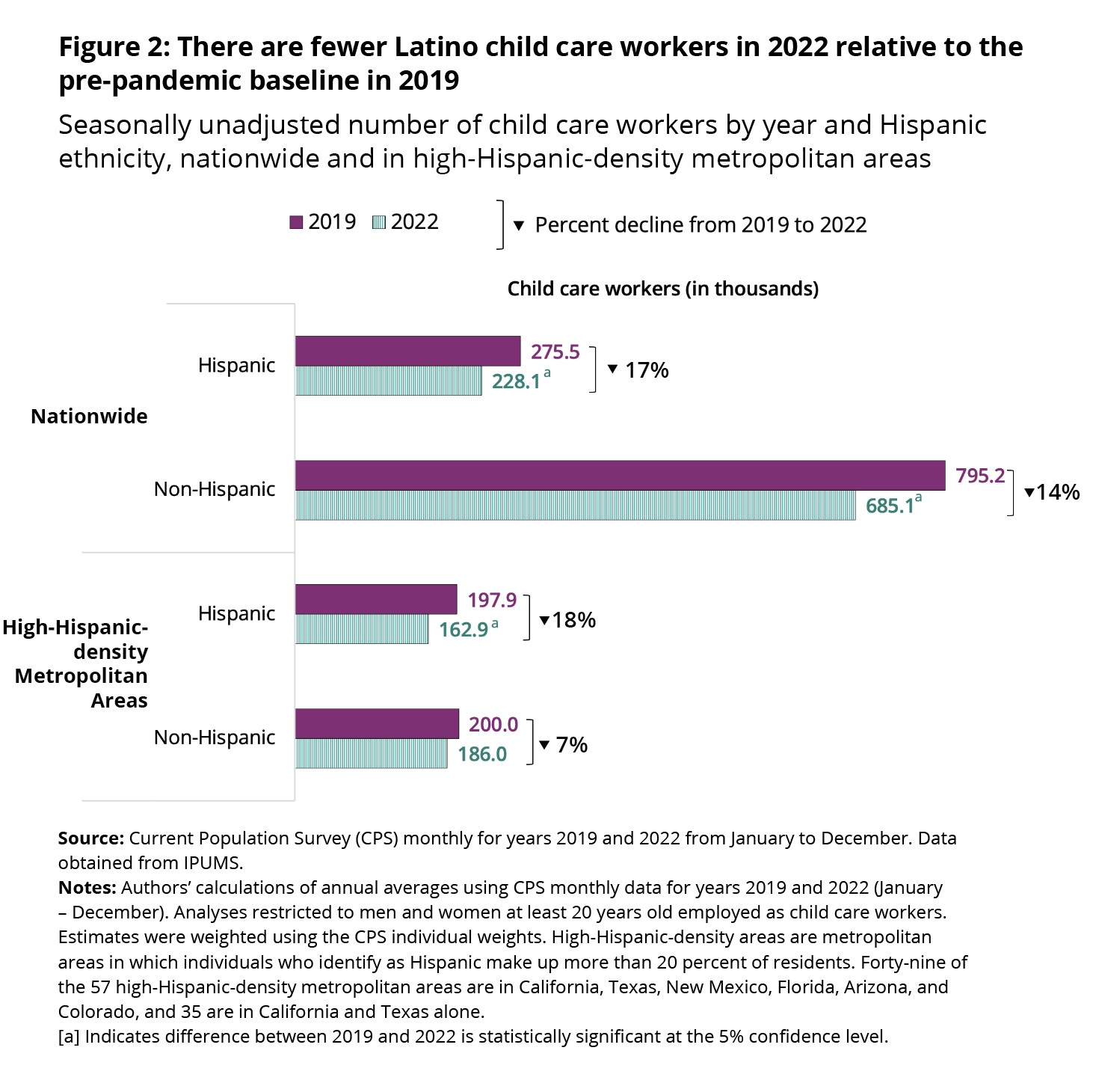

Our analysis found that unemployment rates among child care workers in high-Hispanic-density metropolitan areas increased more steeply at the onset of the COVID-19 pandemic and that unemployment rates among child care workers in these areas recovered more slowly than for workers in all other occupations combined. We also found that, in 2022, there were fewer Latino child care workers relative to the 2019 pre-pandemic baseline, especially in high-Hispanic density metropolitan areas.

About this snapshot

This data snapshot is part of a series documenting how Latino children, families, and households have been faring since the onset of the COVID-19 pandemic. Each snapshot draws from the latest publicly available data sources to examine a specific domain of child and family well-being and provide a brief overview of the social and policy context relevant to the findings. Recent snapshots have focused on mental health, poverty, housing, food, and multiple hardships experienced by Latino households with children. This snapshot follows two earlier pieces examining child care-related disruptions to work experienced by Latino parents at the start of the pandemic and subsequent recovery. In this snapshot, we contextualize those earlier analyses by examining changes in child care employment since the onset of the COVID-19 pandemic.

At the start of the COVID-19 pandemic, unemployment rates among child care workers in high-Hispanic-density communitiesc increased by almost 24 percentage points, from 8 percent in the first quarter of 2020 to 31 percent in the second quarter. This compares with a 21-percentage-point increase nationwide—from 6 to 27 percent—over the same time period. Unemployment rates among all other (non-child care) workers increased from roughly 4 percent to nearly 12 percent nationwide, and from 4 percent to 14 percent in high-Hispanic-density communities, from the first to second quarter of 2020—an increase of 8 and 10 percentage points, respectively. Unemployment rates among child care workers in high-Hispanic-density metropolitan areas remained higher for most of 2020 and part of 2021 compared to nationwide trends, and compared to unemployment rates in all other occupations in both high-Hispanic-density areas and nationwide. By 2022, unemployment rates had recovered both nationwide and in high-Hispanic-density communities.

Changes in Child Care Employment from 2019 to 2022

More than two years after the onset of the COVID-19 pandemic, the number of child care workers is still below pre-pandemic levels, especially among Latino child care workers.

In 2022, the number of Latino child care workers remained 17 percent below the 2019 baseline, both nationwide and in high-Hispanic-density communities. This gap represents over 47,000 fewer Latino child care workers nationwide, but the decline is primarily driven by high-Hispanic-density communities where, in 2022, there were roughly 35,000 fewer Latino child care workers than in 2019. Nationwide, the number of employed non-Hispanic child care workers is roughly 14 percent lower compared to the pre-pandemic baseline, although the non-Hispanic workforce has recovered to nearly pre-pandemic levels in high-Hispanic-density communities.

Conclusion

In line with other work, including the Poverty Solutions initiative’s analysis, we find that the COVID-19 pandemic substantially impacted employment in the child care sector nationwide, with unemployment rates reaching 27 percent at the onset of the pandemic and with fewer child care workers in 2022 relative to the pre-pandemic baseline. Adding to this body of work, we show that high-Hispanic-density communities were particularly affected by child care-related job losses. Unemployment among child care workers in high-Hispanic-density communities reached 31 percent in the second quarter of 2020 and experienced a slower recovery than the nation as a whole. In 2022, two years after the start of the pandemic, there were fewer child care workers than before the pandemic. As a percentage of the pre-pandemic baseline, the decline in employment has been largest among Latino child care workers nationwide and in high-Hispanic-density communities.

Access to reliable child care is critical for parents’ employment and, by extension, for a robust overall workforce. This dynamic is especially significant for Latino families and child care workers. Throughout the pandemic, 20 to 30 percent of Latino parents reported a child care-related work disruption. Our pre-pandemic estimates indicate that Latino parents lost an average of one week of wages per quarter as a result of these disruptions, a figure that was likely to have been much higher during the pandemic. Employment-wise, Latino child care workers account for one quarter of the child care workforce nationwide and roughly half of the child care workers in high-Hispanic-density areas;d additionally, in 2019, one in five early care and education teachers and caregivers worked in settings where 25 percent or more of enrolled children were Hispanic. However, as our analysis has shown, the pandemic took a higher toll on the workforce in Latino communities and among Latino child care workers. Efforts to rebuild the early care and education workforce should be tailored toward the needs of this population of workers, especially in Latino communities, and researchers and policymakers should work to better understand the drivers and consequences of these workers’ exit from the child care sector. Research and policy efforts should include work to address inequities in the overall sector’s wages and compensation.

Methodology

We analyzed data from the Current Population Survey (CPS) obtained from IPUMS.org. The CPS collects monthly data on employment and other economic indicators from a nationally representative sample of households in the United States. We used the CPS because it allows us both to identify child care workers using occupation codes (census code 4600, standard occupational classification code 39-9011) and the metropolitan areas with the highest shares of Hispanic residents in 2019. Because the onset of the COVID-19 pandemic may have affected population movements and the distribution of populations across metropolitan areas, we used the 2019 (pre-pandemic) share of Hispanic residents to identify communities with high densities of residents who identify as Hispanic. We considered high-Hispanic-density metropolitan areas to be those where more than 20 percent of residents identify as Hispanic. Of these 57 high-Hispanic-density metropolitan areas, 49 are in six states: California, Texas, Florida, Arizona, Colorado, and New Mexico. Of these, 35 are in California and Texas.

We restricted our analyses to workers ages 20 and older who are in the labor force and calculated quarterly unemployment rates among child care workers (workers who care for children in schools, businesses, private households, and child care centers, excluding preschool teachers) and among workers in all other occupations (excluding farm workers), both nationwide and for high-Hispanic-density metropolitan areas from the first quarter of 2019 to the last quarter of 2022. We also calculated the annual average number of child care workers who are Hispanic and non-Hispanic for the entire country and for high-Hispanic-density areas in 2019 and 2022 and calculated the change in 2022 as a percentage of the 2019 baseline.

We also tested whether differences between these two time points are statistically significant at the 5 percent confidence level. All analyses were weighted using individual weights. We included all child care workers in our analyses, the vast majority of whom (roughly 95%) are women.

While response rates in the CPS were lower during the first months of the pandemic, especially among certain rotation groups, the Bureau of Labor Statistics (BLS) has used these data to produce employment numbers that meet their accuracy and reliability standards. We validated our quarterly and annual estimates against their tables when available. We found a less than one percentage point gap between our employment estimates and those of the BLS.

Footnotes

a We use “Hispanic” and “Latino” interchangeably throughout this report. The terms are used to reflect the U.S. Census definition to include individuals having origins in Mexico, Puerto Rico, and Cuba, as well as other “Hispanic, Latino or Spanish” origins.

b Forty-nine (86%) of the 57 metropolitan areas we identified as high-Hispanic-density are in sex states: Texas, California, Florida, New Mexico, Arizona, and Colorado; 35 are in California and Texas alone.

c We also use the term “communities” interchangeably with “metropolitan areas,” largely to emphasize the connectedness of residents and jobs within these areas.

d Authors’ calculations using the Current Population Survey.

Suggested Citation

Laurito, A., & Guzman, L. (2023). Top Latino metro areas saw large declines in child care employment early in the pandemic, with slow recovery among Latino child care workers. National Research Center on Hispanic Children & Families. DOI: 10.59377/618h9115q